Abstract

Nowadays, research on punishment use is limited and inconsistent, especially within the clinical field. Thus, within Psychology in general, and within Clinical Psychology in particular, a group of inexact beliefs are still held, beliefs about the use of punishment identified only with a physical assault, not taking into account the punitive potential of the verbal behavior. In fact, verbal punishment is a tool widely used by the clinical psychologist in order to shape the client’s behavior in therapy. The main goal of this paper is to contribute to develop a body of accurate knowledge on the punishment process. More precisely, it is pretended to determine what kind of the client’s behaviors are verbally punished by the therapist in the behavioral therapy settings. In this approach, 21 therapy sessions led by 4 expert psychologists in the course of 9 different clinical cases were observed. Using the instrument SISC-INTER-CVT, 51 therapist’s verbalizations were selected, verbalizations categorized as high punishment (19) and medium punishment (32). Next, the client’s behaviors preceding those punishment verbalizations were observed. Observations showed that the therapist punishes those client’s verbal or non-verbal behaviors impeding the achievement of the therapeutic goals or complicating the therapy progress. From these observations, a categorization system was developed to classify the client's behaviors punished by the therapist.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Generally speaking, psychological research on punishment is limited, sometimes tendentious, frequently inconsistentand difficult to interpret in a clear and homogeneous way. The lack of an accurate knowledge on punishment is especially serious within applied fields of Psychology, standing out the clinical field. As a consequence, both Psychology in general, and Clinical Psychology in particular showed a clearly unfavorable attitude towards punishment study and use. Intentional and systematic use of punishment is understood as a procedure to avoid and it is considered that “punishment must always be used as a last resort” (Martin & Pear, 1983). Even though this conception is based rather on prejudices than on empirical data, the truth is that it has given rise to a complete series of widely accepted ideas, both by general public and by Psychology professionals. Thus, in general terms, the speech valuing punishment is normally focused on the following:

1. Punishment has multitude of undesirable consequences, such as aggressive behaviors, negative affective states,generalized elimination of responses, interruption of social relationships, escape or avoidance behaviors, etc. whose importance and gravity are higher than the possible advantages derived from its application.

2. Punishment is ineffective as far as elimination of behaviors is concerned, since punished behavior usually increaseswithin contexts in which punishment is no longer present and/or is usually replaced by another inappropriate behavior.3. Punishment represents not only uneasiness and humiliation for the person receiving it but it also affects negatively theperson applying it, making it possible to turn this person into someone sadistic, cruel and insensitive to someone else’s suffering.

So, of these statements characterizes the obtained results with duly applied punishment proceedings (Johnston,1985). This does not mean that what the three former points assert does not occur when punishment is used, but that they are not consequences inherent in the use of it, occurring inevitably in every kind of punishments, in every situation, and with every subject. The present study is carried out to give an answer to this situation, and its goal is to contribute to the development of a deeper and more accurate knowledge about the punishment process and, as it will be detailed further on, about its role in behavioral therapy. Research on punishment is required to put an end to unfounded beliefs predominating in it and to make it occupy its rightful place both in research and in psychological praxis.

This study is placed within the line of research on verbal behavior in clinical settings carried out by the group ACOVEO in the (Autonomous University of Madrid) (Froján, Calero & Montaño, 2011; Froján, Montaño & Calero, 2006; Froján, Montaño, Calero & Ruiz, 2011; Froján, Pardo, Vargas, & Linares, 2011). The main goal of this research team is to study the processes explaining the therapeutic change through the testing of the verbal interaction in clinical settings, using observational methods. Within this line of research is considered that the behavioral paradigm is the best choice for a scientific approach to the study of behavior, specifically with regard to the proposal of considering the therapist-client interaction as a process of shaping, but also to the explanation of language observed in clinical settings in terms of classical and operant conditioning, and the conceptualization of behavior therapy as the application of basic behavioral operations for the treatment of psychological problems. Placed in this context and assuming its theoretical and methodological background, the main goal of this study is testing how punishment is used in a real therapeutic context, determining what kind of the client’s behaviors are punished and what kind of effects its application in the therapy development has. This purpose rises mainly from the results of two former studies. Firstly, from the study carried out by Ruiz (2011) on therapist-client verbal interaction in the course of the therapy. In this research, a (SISC- INTER- CVT) was developed to test the existing connection between the therapist’s and client’s verbalizations in the course of the therapy. One of the initial hypotheses of that study was that the client's verbalizations included in the group of "Anti-therapeutic verbalizations" would be followed by therapist’s verbalizations classified as “Punishment function”. Even though the hypothesis is confirmed, a detailed analysis of the results showed that the verbalizations classified as "Fail" or “Uneasiness” were not only reduced at the end of the therapy but they were even increased. The author proposed several reasons explaining this increasing: The development of dependency to the therapy in the last stages of it, the competition of external

reinforcement to verbalizations punished in therapy, and the lack of systematicity in the application of punishment by the therapist. In light of this stimulating result, an interest in deep analysis of the connection between the therapist’s punitive verbalizations and the client’s behavior in therapy arose. Secondly, the study carried out by Froján, Galván, Izquierdo, Ruiz, & Marchena (2013) was also a basis for the present work. In the aforementioned investigation a complete clinical case was tested with the goal of determining how some client’s verbalizations were evolving (called in the study “Maladaptative Verbalizations”) and how these verbalizations were connected to the therapist’s punishment verbalizations. The first step was to create a system to categorize the client’s “Maladaptative Verbalizations” and to test its dynamics in the course of the therapy, obtaining an overall decreasing trend as a result. After that, the connection between the therapist’s punitive verbalizations and the client’s behavior was tested, and the results were that, contrary to expectations, punishment was barely applied to “Maladaptative Verbalizations”, but it was applied especially to another kind of the client’s verbalizations and behaviors which, because of their form and content, meant an obstacle for the therapy progress. This work is directly linked to the results of the aforementioned study and expects to determine what kind of the client's behaviors are the ones which, actually, the therapist punishes. More specifically, it is proposed to fix what kinds of the client’s behaviors precede the therapist’s punitive verbalizations, as well as to organize these behaviors in a categorization system useful for future investigations. In this way, it is expected to test the hypothesis of the therapist applying verbal punishment to those client’s verbal or non-verbal behaviors impeding or complicating the therapy progress.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

In order to carry out the study, 21 therapy sessions recordings from 9 clinical cases led by 4 behavioral therapists withdifferent grades of experience were tested. Clinical work was carried out with adults and individually. Every session took place in the private psychological center “” (Therapeutic Institute of Madrid) and, pursuant to the Spanish Psychologist Code of Ethics (art. 40 and 41), both its recording and its transfer for the present study had the informed consent of the client, the therapist and the center management. In order to warrant to the maximum the clients’ confidentially rights, the cameras recording the sessions were only directed to the therapist and in no event the client's face was registered.

2.2 Variables and instruments

In order to define what kind of therapist’s verbalizations could be categorized as a punishment, it was used the SISC-INTER-CVT (Ruiz, 2011), a recently developed categorization system of client-therapist verbal behavior in session. Within this system, the category Punishment is defined as that “therapist’s verbalization which, interrupting or not the client’s verbalization, shows disapproval, rejection and/or non-acceptance of the behavior performed by the client.” (Ruiz, 2011). Those therapist’s verbalizations can express disagreement with the client’s verbalizations content, can have as an aim the fact of interrupting or avoiding their speech or both of them simultaneously.

Examples:

- Client: “Well, I can tell him/her: I am here, if you need anything, you know.” - Psychologist: “Yes, but there exist different ways to say it. Not like that, as if you were an operator” (Punishment function aimed at the content expressed by the client).

- Client: “Yes, but it was a mix. It was good because I feel good for having been able to do this, but it was bad too

because I, I… I don’t know, it was one more snub to me and I didn’t like it at all.”

(Punishment function aimed to interrupt the client’s speech).

They were considered as punished behaviors those client’s verbal or non-verbal actions preceding immediately the therapist’s punishment verbalizations. It was decided to include the client’s non-verbal behaviors fully aware that they could only be inferred from the conversation (since, as it has been mentioned before, the camera did not record the clients and it was not possible to see what they were doing). It was considered that an analysis of behavior punished by the therapist excluding the client's non-verbal behavior would be incomplete and would be inadequate. Because of this, it was decided to include the client’s non-verbal behavior in this study, taking always into account that it was an inferred behavior and dealing with drawn results and conclusions from it with due consideration.

The recording of the analyzed sessions was made using a close-circuit cameras and video system in the collaborating center. The image recorded on a VHS video was later transformed into a MPEG-2, format required by the software used for its observational analysis. The software used for the session’s observation and register was the The Observer XT 6.0 version, commercialized by Noldus Information Technology.

2.3 Procedure

The investigation began with the location and selection of a big enough sample of therapist’s verbalizations categorized as punishment according to SISC-INTER-CVT. To do that, the database of therapist's and client’s verbal behavior register created by our investigation group was consulted. It is formed by more than one hundred therapy sessions registered by SISC-INTER-CVT. After consulting the aforementioned database, a total of 51 therapist’s verbalizations were selected, 19 of them categorized as high punishment and 32 as medium punishment. Next, two investigators with a wide theoretical education observed, independently, the client's behaviors preceding the selected punishments, elaborating a first informal register of them. In order to avoid an analysis out of context which could lead to conclusions guided by the observers’ previous ideas or conceptions more than by facts, both the therapist’s punishments and the clients' behaviors were always analyzed within the clinical session setting where they took place. Thus, both the observation and the register were not limited to the punishment verbalizations and client’s behaviors immediately preceding them, but they were expanded to the complete conversation in which they had taken place in order to contextualize them adequately. Once completed this task, all the preliminary registers were put together and all the observations were analyzed and discussed until reaching a common point of view in this regard. Then the process of building the categorization system of the client’s behaviors punished by the therapist began. From previous observations and discussions, each investigator developed a first proposal of categorization. Later, and with a clinical psychologist and expert investigator advice, the different proposals were put together and discussed until developing a joint and final categorization system.

3. Results

The observation and analysis of the therapy sessions provided interesting discoveries about what kind of the client’s

behaviors are punished by the therapists. In general, it was observed that:

-The therapist punishes a range of the client’s behaviors, both verbal and non-verbal. In other words, the therapist does not only apply punishment to things that the client but also to things that the client. As far as the client's nonverbal behavior is concerned, it is considered important to insist again that it was only possible to infer it from conversation since cameras were not recording the clients and it was not possible to watch their non-verbal behavior.

-In relation to the client’s verbalizations, the therapist can punish them because of its (its meaning, what they are expressing) or because of its (how and/or when they are produced).

-Frequently, the therapist uses punishment verbalizations to stop the client’s speech, speak and call their attention to

something or emphasize something important.

-The therapist can also apply punishment to those behaviors which are produced out of the clinic, but only in anway through the account of those behaviors told by the client. This discovery links directly with investigations on behavior-behavior relations and say-do correspondence. Without going into specifics, the mentioned investigations are interested in the connection made between what the subject says that they are going to do and what they finally do or between what the subject does and their subsequent verbal report, as well as in the variables affecting the acquisition, maintenance, and generalization of that connection (Baer, Detrich, & Weninger, 1988; Israel & O'Leary, 1973; Lima & Abreu-Rodrigues, 2010; Luciano, Herruzo, & Barnes-Holmes, 2001). The general premise is that the human being is able to establish a connection between what is said and what is done, in such a way that it is possible to influence their actions through the verbal report made about them. In this way, the therapist can modify the subject’s behavior without interceding directly in it, acting on the description that the subject makes about that behavior. Thus, when the therapist punishes the client’s account about their behavior out of the clinic, what the therapist is doing is punishing that behavior in an indirect way, using the connection established between the subject’s behavior and the description that he or she makes about it.

System of categories of the client’s punished behavior:

Table 1 shows the system of categories developed to organize the client’s behaviors punished by the therapist.

Distribution of the client’s punished behaviors according to the system of categories:

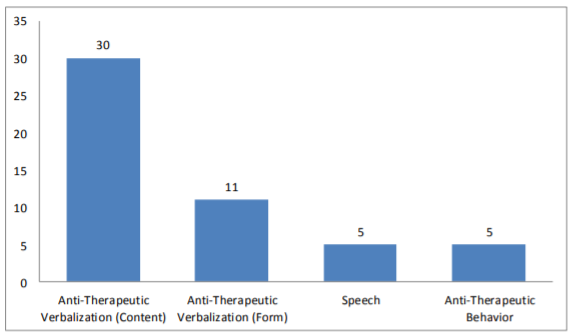

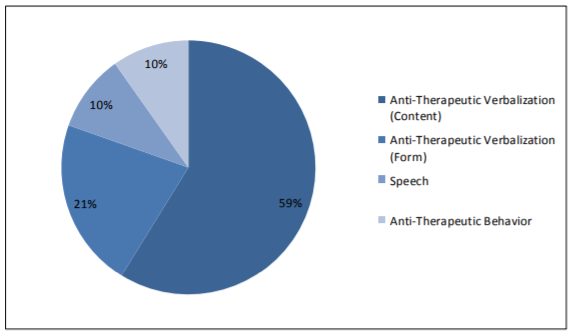

It is presented below how the client’s punished behaviors were distributed into the four classification categories developed:

As it can be clearly observed, in both figures, therapist’s behaviors were mostly aimed at the client’s verbalizations expressing some kind of content opposed to the therapy goals. Specifically, 59% of punishment verbalizations were aimed at this kind of the client’s behaviors. Secondly, there appear the client's verbalizations which, due to how or when they were produced, became an obstacle for the therapy progress. This kind of behaviors meant 21% of the total of the punishment verbalizations analyzed. Finally, both the categories “Anti-therapeutic behavior” and “Speech” implied 10% of the total of the therapist’s punishments included within this study.

Discussion

As it has been mentioned before, this paper is a first descriptive approach to the role played by verbal punishment inclinical settings. It has been observed that the therapist applies punishment verbalizations to certain client’s behaviors which can be grouped into different general categories. If it is possible to presuppose that the therapist’s goal is to reduce or eliminate those client's behaviors, it is not possible to claim that punishment verbalizations applied by the therapist have a punishment function. In order to check if punitive verbalizations work as punishments in the functional sense of the term, that is reducing or eliminating the preceding behaviors, it would be needed to change the method of study from observational analysis to manipulation of variables. It is then resumed the distinction between punishment as a process and punishment as a procedure which was already mentioned in the introduction. It is vitally important to point out that the focus of this study is the procedure or technique of punishment and that the statements released here are referred only to punishment as a procedure, not as a process. In any case, the observation and analysis of the punitive verbalizations use made by the therapist in the course of the therapy is a first and necessary approach and it means interesting discoveries.

Firstly, it has been observed that the therapist applies their punishments to a range of client’s behaviors, either verbal or non-verbal, and which can happen either in or out of the clinic. The common thing in all these behaviors is that, either because of its form or its content, they impede or complicate the therapy progress and/or the achieving of the therapeutic goals. In that sense, these client’s behaviors can be referred to as “anti-therapeutic behaviors”, since they would impede the optimal development of the intervention. Thus, verbal punishment is a resource used by the therapist to control the client’s behavior, stressing those behaviors meaning an obstacle in the therapy progress. However, two important specifications on these observations must be highlighted, even if they have been previously mentioned, it is considered relevant to include them in this section. The first one, it is advisable to remember that the client's non-verbal behaviors could only be inferred from the conversation held with the therapist, since cameras were not recording them directly and it was not possible to see what they were doing. Although the information in the conversations was enough to get a quite clear image about what the clients were doing, it is not possible to assert it with certainty and that can threaten the work validity. The second one, as far as the behaviors out of the clinic are concerned, the therapist can only punish them in an indirect way through the subject's verbal report. As it was previously stated, this matter links directly with investigations on behavior-behavior relations and say-do correspondence. Human beings are able to establish a connection between what is said and what is done, in such a way that it is possible to influence their actions through the verbal report made about them and vice versa. Applied to the therapeutic setting, the clients establish a connection between their behavior out of the clinic and the account about that behavior made in the clinic. The therapist can use that connection to influence the behaviors happening out of the clinic, acting on the verbal report made about them by the subject. Thus, the therapist can punish a subject’s inadequate behavior happening out of session through the client’s verbal description about that behavior.

A detailed analysis of the behaviors punished by therapists allowed to group them into four categories:,,,. This categorization system can become a base for different investigations on the dynamics followed by the clients’ antitherapeutic behavior in the course of the therapy, the therapists’ answers to those anti-therapeutic behaviors, and the interaction between both of them. However, before going to that approach is needed to test and optimize the categorization system which is still at a very early stage. The categories have been set from systematic observation and subsequent discussion of the clients’ behaviors, but they have not been applied to a new sample and its reliability has not been determined. Thus, the next natural step in this line of research would be optimizing the system of categories by being tested by different observers in a new sample with the goal of detecting and solving possible problems (definition, number of categories, reliability, completeness, and exclusiveness of the categories…). Once this is done, the system of categories will be able to be used to research with scientific precision the connection between the clients' anti-therapeutic behaviors and the therapists’ punishment verbalizations.

When analyzing how the clients’ behavior were distributed according to the system of categories, it was found that most of the therapists’ punishments aimed at behaviors categorized as. Specifically, 59% of the punishment verbalizations analyzed were applied to client’s verbalizations showing ideas or beliefs opposed to the therapy goals. Thus, it seems that what the therapists punish the most are those clients’ verbalizations expressing inadequate interpretations of reality, either referred to themselves, to everybody else, to the situation, or to the therapy in itself. It must be pointed out that this discovery could lead us to think that the therapist punishes most of clients’ verbalizations with an anti-therapeutic content, however, that is a statement not possible to make with the existing the data. The only valid statement is that, in the analyzed sample, most of the therapists’ punishments aimed at clients’ verbalizations with an anti-therapeutic content. It is very important to take this into account when interpreting the results discussed here, both for this category and for any other else. Secondly, behaviors categorized as are found, which mean 21% of the analyzed punishments. In this case the problem was not the content expressed in the verbalizations, but how or when they had taken place. Finally, both the categories and behavior had 10% of the analyzed punishments. Thus, out of the total amount of the punishments included in this study, 90% aimed at the client's verbal behavior, either because of its content, its form, or just because of happening when the therapist wanted to point out or emphasize something. This is not surprising if we consider that the therapy is carried out basically through verbal activity, which is the main tool at the psychologist’s disposal to shape the client’s behavior and achieve the therapy goals.

In conclusion, the analysis of the therapist’s punitive verbalizations and the client’s behaviors towards they aim at showed that the verbal punishment is a useful and necessary tool to guarantee the therapy progress. The therapist punishes those client’s behaviors, both verbal and non-verbal, which because of its content or form complicate the therapy development and the achieving of the therapy goals. However, this is only one of the first steps in the study of the verbal punishment role in behavioral therapy. There is still a great research to do about how the therapists use the verbal punishment and how the therapist interacts with the client’s behavior. It would be interesting to refine the system of categories in order to determine the extent of the therapist punishing the client’s anti-therapeutic behaviors and other behaviors happening before them. It would be also interesting to research the interactions produced between the therapist’s punitive verbalizations and the client’s behaviors, as well as to determine if those punitive verbalizations work as punishments in the functional sense of the term. Thus, many lines of research worth to study appear now, with the ultimate goal of expanding and improving our knowledge about verbal punishment, about what are its risks and advantages, how can it help us to guarantee the correct therapy development, and what is the most effective way to apply it and has the least undesirable side effects.

References

Baer, R.A, Detrich, R & Weninger, J.M. (1988) On the functional role of verbalization in correspondence training procedures. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 21, 345–356

Froján, M. X., Calero, A. & Montaño, M. (2011). Study of the socratic method during cognitive restructuring. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 18, 110-123

Froján, M. X., Galván, N., Izquierdo, I., Ruiz, E. & Marchena, C. (2013) Análisis de las verbalizaciones desadaptativas del cliente y su relación con las verbalizaciones punitivas del terapeuta: un estudio de caso. In review.

Froján, M. X., Montaño, M., Calero, A & Ruiz, E. (2011) Aproximación al estudio funcional de la interacción verbal entre terapeuta y cliente durante el proceso terapéutico. Clínica y Salud, 22, 69-85.

Froján, M. X., Montaño, M. & Calero, A. (2006). ¿Por qué la gente cambia en terapia? Un estudio preliminar. Psicothema, 18, 797-803.

Froján, M. X., Pardo, R., Vargas, I. & Linares, F. (2011) Análisis de las reglas en el contexto clínico. EduPsykhé, 10 (1), 135-154.

Israel, A.C & O'Leary, K.D. (1973) Developing correspondence between children's words and deeds. Child Development, 44, 575–581

Johnston, J (1985). Controlling professional behavior: a review of “The effects of punishment on human behavior" by Axelrod and Apsche. The Behavior Analyst, 8 (1), 111-119

Lima, E.L. & Abreu-Rodrigues, J. (2010) Verbal mediating responses: effects on generalization of say–do correspondence and noncorrespondence. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 43(3), 411-424.

Luciano, M.C, Herruzo, J & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2001) Generalization of say-do correspondence. The Psychological Record, 51, 111–130.

Martin, G., & Pear, J. (1983). Behavior modification: What is it and how to do it. Englewood Cliffs, N.J. Prentice-Hall.

Ruiz, E. (2011) Aproximación al estudio funcional de la interacción verbal entre terapeuta y cliente durante el proceso terapéutico. Unpublished doctoral dissertation defended at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Faculty of Psychology, Department of Biological Psychology and Health.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

14 May 2014

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-000-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

1

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-236

Subjects

Social psychology, collective psychology, cognitive psychology, psychotherapy

Cite this article as:

Dominguez, M. N. G., Beggio, M. G., Cebrian, M. R. P., Arroyo, M. A. S., & Frojan-Parga, M. X. (2014). Verbal Punishment in Behavioural Therapy. What does the Therapist Punish?. In Z. Bekirogullari, & M. Y. Minas (Eds.), Cognitive - Social, and Behavioural Sciences – icCSBs 2014, vol 1. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 87-97). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2014.05.11