Abstract

The objective of this paper is to develop a set of family business parameters to ensure business survival in the market, particularly during and after the post-pandemic of COVID-19. This study investigates how the family business in Malaysia plan their strategy(s) to be resilient and agile for business sustainability and continuity during COVID-19 pandemic. This study explores the critical success factors that contribute to the family business response for sustainability. Nevertheless, issues regarding family conflict and business survival are the biggest challenges for a family business to strengthen its resilience and continuity. The current paper employs a content analysis approach on the STEP and KPMG, COVID-19 report findings, and a review of previous literature and past studies in Malaysia on the family business landscape. This paper focuses and highlights the results and findings on Malaysia and some related aspects and compares Malaysia’s standings against family businesses in Europe, the Americas, Asia, and the Middle East and Africa (countries that participated in the STEP & KPMG 2020 study). Through the content analysis findings, propositions of a model are developed in order to address the issues and challenges towards family business growth and survival in the market. This paper presents (i) several propositions regarding family businesses strategy in Malaysia and (ii) critical success factors in sustaining the family businesses in Malaysia. This study also shows family business governance variables that are vital to respond to the challenges and opportunities in a given situation.

Keywords: Family business, strategic management, sustainability

Introduction

Family businesses are prevalent and known as the world’s oldest and dominant form of business organisation. In many countries, family businesses play a vital role and contribute to a country’s economic growth. It is also reported that 70 per cent of the overall business in the world presents family businesses (Porfírio et al., 2020). In Malaysia, family businesses are part of the nation’s economic foundation.

The size of family businesses ranges from small to large conglomerates that operate in multiple industries and countries. Some renowned family businesses globally are Carrefour Group in France, Fiat Group in Italy, and Samsung in South Korea. These are among the family businesses that are successfully established yet continuously survive in the capital market. The success of these family businesses has been transcended from one generation to another. On the other hand, some family businesses have a limited life span beyond their founder’s stage, and often 95 per cent of family businesses do not survive in the third generation ownership (Boyd et al., 2015; Mokhber et al., 2017). Previous studies, such as Mokhber et al. (2017), have shown that one of the reasons that contribute to the survival period of family businesses is the lack of preparation of the subsequent generations to manage the demands of a growing business and much larger family involvement in the organisation. Family businesses are typically vulnerable to their autonomous, family-oriented principles and constrained resources (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007; Lee, 2006). In addition, in certain crises, family businesses tend to have different practical actions compared to other organisations because of the emotional attachment of the family and family businesses (Arrondo-García et al., 2016; Faghfouri et al., 2015). Consequently, the actions influence the family businesses to sacrifice short-term performance and shareholder value for long-term survival (Minichilli et al., 2016).

Having withstood that family businesses are unique and different in the form of their attributes and governance from other organisations, these leave a deep impact on the level of resilience and agility on the sustainability of the businesses as well as the economic growth of a nation. Scholars in the family business field (such as Arrondo-García et al., 2016; Leotta et al., 2017; Mitter et al., 2012; Stewart & Hitt, 2012) contended various factors that can contribute to the survival and growth of a family business. The majority of scholars argued that business size, industry, family members’ involvement, generation, and business principles and norms are among the influential factors that affect the sustainability and growth of a family business. Bhatt and Bhattacharya (2015), for example, found that board size has a significant association with the level of family business performance. Findings from the analysis of the board size show that family member involvement in the context of an independent chairman and smaller size of the board are vital to ensure the direction of the company. In addition, Evert et al. (2018) found that intergenerational family members’ involvement plays an important role in making strategic decisions for a family company (see also Davis & Harveston, 1998). Findings from the study indicate that the strategic behaviour of family members on the board explains the company’s willingness and ability to engage in major strategic initiatives and directions for the company. In this context, Evert et al. (2018) posit that strategic decision making is based on the family priorities rather than external stakeholders’ preferences (see also Zaini et al., 2020).

Family business management differs from non-family business when a crisis occurs or hits. They are sometimes twice stressed by crises, one concerned with the family source of income, and one as business owners who expect the continuation of the business to the next generation. Previous research found that family businesses and their management, as well as internal family relationships, may influence the survival of the companies (Melin et al., 2013; Porfírio et al., 2020). The family business affairs and management are likely to have clashes between internal family relationships such as family role expectations, mutual goals, conflict resolution, generations as well as family innovation. Besides that, external factors such as government and other agencies assistance also can drive the survival of the family businesses. Family business persistence is often associated with long-term sustainability. Previous studies such as Stamm and Lubinski (2011) found that approximately only 30% of family businesses go further than the first generation, and between 10% and 15% manage to reach the third generation (see also Pyromalis & Vozikis, 2009). Passing the family business to the next generation can be a very subjective matter and have a profound and significant effect on family members.

On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) announced the unprecedented situation of coronavirus disease, COVID-19, widely spread throughout the world. Since then, the pandemic outbreak has caused an alarming global health crisis. Many countries have taken various drastic actions to respond to the situation affecting the daily life of society. One of the ways to slow the transmission and spread of the virus is to enforce ‘lockdown’. Many regions and even countries have enforced the initiative which is implemented in schools, universities, public areas, public events and public centres or facilities.

Since then, these actions have affected the populations’ daily lives and significant economic consequences in economics worldwide. Some countries experience a dramatic economic crisis (Baker et al., 2020), and economists consistently forecast harsh economic conditions, including recessions, due to non-operational businesses and unemployment. The imposition of government health protection policies and lockdown orders to non-essential businesses and rigid instructions on essential businesses in many countries has triggered an imbalance of supply and demand in the economy.

This study aims to identify the differences between family businesses in Malaysia and other countries in response to the global pandemic COVID-19 for its survival circumstance. The objective of this study is to ascertain the crucial factors, either external and/or internal factors, of the family firms. It is acknowledged worldwide that family firms are the predominant form of business (Claessens & Fan, 2002; La Porta et al., 1999; Villalonga & Amit, 2020). Prevalence studies have shown that family firms are typically vulnerable and altruistic due to their complex connection between business management, financial capital and resources, and family-oriented standing. As mentioned beforehand, family firms are likely to face conflicts during crises because of their behaviour and family-business relationship.

Therefore, the research questions for this study are as follows:

Does the involvement of family generations affect the family business strategy decision in a crisis?

What are the components for a family business’ long term growth and survival?

This paper makes several important contributions to the family business sector. First, this study provides further insight and explains the current situation of family involvement in businesses and their strategy to ensure the business continuously survives in a crisis. Second, this paper also contributes to the importance of governance elements in family businesses, particularly in emerging economies.

Situation setting: the pandemic crisis implication

The COVID-19 crisis has an enormous impact on the economy globally. Governments in developed countries such as in the US and Europe have taken precautions for business and financial stability. Multiple stimulus packages for businesses have been released for various industries to ensure the continuous operation of these businesses. While few industries such as pharmaceutical and healthcare as well as the rubber industry have increased demand and are benefiting from this crisis compared to other industries. These are among the industries that continuously operate, while others, such as restaurants, tourism and hospitality, hotels and entertainment, are severely affected. The government control order and/or restrictions caused closure by many affected businesses in the industries. Public places such as shopping malls, restaurants, and cinemas (as well as sports facilities, museums, theatres) are forced to close and lead to severe setbacks in these industries. However, in the food or restaurant industry, food delivery or pick up have been allowed.

Following the closure of businesses, it is clear that the economic condition of countries is at a bottleneck. The majority of the countries, including Malaysia, have taken measurement steps to recover and rescue their economy through stimulus packages worth USD91 billion (as recorded in June 2021). These enormous measures have been taken based on the estimations of economic development, which the economists predict as a significant economic downturn exceeding those of all previous crises in the global economy for the long term. Since 2020, Malaysia has issued seven stimulus packages to its citizens. The stimulus package included wage subsidies, unemployment assistance, and cash aid.

The first stimulus package valued at RM20 billion was issued by the former Prime Minister of Malaysia, Tan Sri Dato’ Muhyiddin Mohd Yassin. This emergency stimulus package announced on 27 February 2020 implements strategies such as spurring economic growth, promoting investments and encouraging businesses to adopt automation and digitalisation processes (https://www.aseanbriefing.com/news/malaysia-issues-stimulus-package-combat-covid-19-impact/ ) . These enormous measures have been taken based on the estimations of economic development, which the economists predict as a significant economic downturn exceeding those of all previous crises in the global economy for the long term.

On 27 March 2020, he unveiled the (PRIHATIN) as the second Economic Stimulus Package. The main aim of the package worth RM250 billion is to provide immediate support and assistance to those who are significantly affected during the COVID-19 pandemic. This enhances the existing financing facilities issues in the first stimulus package. Apart from that, the aim of this stimulus package is also to support the business industries and to strengthen the Malaysian economy. The PRIHATIN package has relieved the burdens of households and businesses, giving a big relief to the affected family business. The package assisted the B40 entrepreneurs by providing initial capital for micro-entrepreneurs using zakat funds and matched with affordable rates of microfinancing. This is important to ensure no one is left behind (PRIHATIN Rakyat Economic Stimulus Package 2020). (https://www.aseanbriefing.com/news/malaysias-pemulih-stimulus-package-supporting-businesses-and-individuals/ )

Deloitte (2020) reported that the third RM10 billion Prihatin Package was announced on 6 April 2020. This package is specifically catered to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The measures include enhanced wage subsidies, waiver of rental, and loan and grant schemes, among others. This shows that the government has consistently put greater measures in assisting SMEs (https://www2.deloitte.com/my/en/pages/tax/articles/stimulus-caring-rakyat-package) .

Malaysia then issued its RM35 billion-ringgit worth of its fourth economic stimulus package on 9 June 2020 named (PENJANA). This package includes new tax incentives, financial assistance for small and medium-sized businesses and job protection initiatives aimed at helping businesses recover from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (https://www.aseanbriefing.com/news/malaysias-penjana-stimulus-package-key-features/) .

In safeguarding the welfare of its citizens and supporting business continuity, the Malaysian government has taken its next step in announcing its fifth stimulus package named (PERMAI). Regarding supporting business continuity, the Prihatin Special Grant Plus assistance has been extended to cover 500,000 SMEs with a payment of RM1,000 each to the seven MCO states, while 300,000 SMEs in other states received RM500 each (https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/pm-muhyiddin-announces-rm15b-economic-stimulus-package-under-permai-scheme) .

In March 2021, the government unveiled the (PEMERKASA) as its sixth economic stimulus package worth RM20 billion. Focusing on the 20 initiatives, the package aimed to jump-start the economy to support business continuity (https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2021/03/18/rm20bil-aid-for-the-people) .

The government also has announced the eighth stimulus package to provide comprehensive assistance to the people facing financial constraints due to the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic. The RM150 billion economic package focuses on three main areas: continuing the agenda, supporting businesses and boosting vaccination (https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2021/06/29/a-comprehensive-package

) .

Concerning the above, it is evidenced that the government of Malaysia has taken a consistent set of initiatives to manage and assist its citizens in different perspectives: social and financial, in facing the pandemic. It is not only focusing on individuals but also on businesses. With the aid of financial assistance, it eases the burden of individuals and helps in terms of the survival of businesses.

Theoretical background and framework

This study, through content analysis approach, seeks to contribute to the family business research stream by examining the comparative report findings between Malaysia and other countries (i.e., Malaysia, Europe, the Americas, Asia Pacific, and the Middle East and Africa) in which the family relationship (which in this study will use ‘familiness’ term) construct within the resource-based view of the firm translates to the formation of competitive advantage during a given setting. Following Villalonga and Amit (2020), this study describes family businesses or family firms as an entity under control or has a significant influence on a family member as an individual shareholder (also known as founder) and/or with other family members. Similarly, Memili et al. (2018) and Mokhber et al. (2017) describe family businesses as ownership in the aspects of management, involvement in the business, generation transfer, as well as governance structure (see also Ibrahim & Samad, 2010).

Family businesses are different from others in various ways. For example, Klein (2000) describes a family business as an organisation that is participated by one or more families in the family business, while Littunen and Hyrsky (2000) defines family business as an organisation that has a single person or single family that has a full controlling system in the family business. In this context, family businesses are dominated by one or two or more family members. Nevertheless, Arteaga and Escribá-Esteve (2020) presented the definition or description of the family business comprehensively; the authors describe that family business is developed in three aspects: ownership, family and management with the family essence as the organisation core (see Diaz-Moriana et al., 2019). The family business may be of different types, including a sole proprietor, partnership, limited companies and holding companies. Following Memili et al. (2018), this paper describes family businesses as an organisation that ‘a family owns all or a controlling portion of the business and plays an active role in setting strategy and in operating the business on the a-day-to-day basis’ (Kelly et al., 2000, p. 28).

With increasing research in the family businesses to explore further in terms of its market orientation, and source of competitive advantage, it is critically important in this area to identify the cultural-based phenomenon and support through the organisation’s core to ensure the organisation has effective market orientation and subsequently survives for a longer-term. The management of family businesses is often handled by family members. Nevertheless, not all family firms have full support from their family members either in control and/or involved in management. The resistance for involvement in family business tends to lead to inappropriate planning and unclear direction, causing difficulty to survive in a capital market.

The level of family business growth and survival period often be the highlights of many researchers in the previous years in various sectors. The rate of family businesses growth and survival have become the central focus in global and local regions. In this context, this study focuses on the concept of sustainability in the aspect of family business ability to maintain or improve the business position and availability of desirable resources and opportunities over the long term. Within this view, the sustainability of the companies refers to the duration of running its operation across the five years from the starting point, which also describes the differences between sustainability and sustainable development. Sustainable development can be defined as ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (Brundtland, 1987). As described in Brundtland (1987), sustainable development focuses on promoting humans and their lives, while sustainability is utilised for the stability of the natural, human and social system (see also Harrington, 2016). Thus, family businesses sustainability is important, particularly in a situation where the market has been distorted by a crisis. Furthermore, according to Rodrigo (2015), within the sustainability-oriented theory of an organisation, ‘the firm is a profit-generating entity in a state of constant evolution. This entity is a system of resources and networks of relationships with stakeholders. The firm’s employees are responsible for representing the firm, managing its resources, and empowering its stakeholders so that the firm complies with laws, maintaining its “license-to-operate”, increases its competitive advantage, and better contributes to fostering the evolution of more sustainable societies by holistically addressing the economic, environmental, social and time dimension’.

Previous literature reveals sustainability of a family business is very much associated with long term orientation, educational background, organisational value, relationship with stakeholders, the involvement of family members, value and size of the family firm and environment (see for example Arrondo-García et al., 2016; Bövers & Hoon, 2021; Mokhber et al., 2017; Oudah et al., 2018). Long term orientation is the ultimate aim for every family business. The long-term orientation is imperative and associated with the implementation of sustainability practices. Along with the application of the practices, the behaviour, involvement and knowledge of the family members in the firm are crucial to ensure efficient and effective response towards economic conditions, particularly in crisis conditions. According to Barnes (2019), some family businesses have difficulties understanding the strategy for remaining competitive within similar industries or sectors. One of the reasons is family involvement and networking, be it at the social and professional level. In this context, family members are considered the main player to gain resources and make decisions for business sustainability. Resources and decision making are intertwined and need higher attention from the family members. To ensure a strategy is successfully executed, some intangible resources must be carefully managed when making economic decisions for business sustainability.

A family business can have its top management consisting of a Board of Directors. The board of directors or managers is considered a provider of resources for the companies. A board having ultimate prerogative rights and a high level of links to the external environment is expected to facilitate accessibility to various resources for the companies (Nicholson & Kiel, 2007). Among the board components which are often associated with resource provision and firm performance include board size, board composition, and board involvement in the business matters.

In the context of family businesses, some companies may have board of directors consisting of family members, be it in a medium or large size (i.e., non-public listed companies). In practice, these managers play their role in the context of directorships because of their position in the companies’ organisational structure. These family managers often consist of the first and second generations of the family. Previous literature also suggests that family members in the top management play a vital role in ensuring the continued survival and growth of the business. Within the resource-based view, family managers often associate with the organisation culture and link their company to external resources for better performance. Family managers are known as the main pillar in the organisation by contributing their knowledge, experiences and skills. These cognitive contributions would bring more expertise and resources, thus improving the company’s performance.

Along with the family businesses context, the involvement of family members can be linked with a succession plan, a process of transferring managerial control from one generation to the next (Mussolino & Calabrò, 2014). Previous literature argued that essential qualities of family businesses result in distinctive organisational behaviour and outcomes. For instance, family members that have close relationships with their large family collectively, durable relationships, and maintain trustworthiness among family members, can develop a strong internal core of family organisation and management (Mussolino & Calabrò 2014; Porfírio et al., 2020).

In the context of organisational crisis and crisis management, every business would have a different approach to encounter the problems. This includes the family businesses, where the organisation should have a strategic response crisis action plan for uncertain situations such as economic crises. This uncertain situation is likely to affect the companies’ performance, resulting in several considerations that the organisation may face. Along this line, ownership, revenues, employees, production line, etc., can be disrupted and probably lead to company bankruptcy or collapse. According to Faghfouri et al. (2015), small-medium enterprises or family businesses should equip their entity with a high degree of crisis readiness action plan in order to reduce the likelihood of bankruptcy or collapse. In this context, the family businesses are expected to establish an appropriate structure of family governance as well as corporate governance so that the family and business can integrate together to form a solid foundation for professional and rational decision making to maintain a high-quality hazard situation preparedness. Nevertheless, previous studies found that the majority of small-medium enterprises or family businesses do not have standard and formalised crisis management procedures. Researchers such as Chua et al. (2009), Sciascia and Mazzola (2008), Martínez et al. (2007) contended that family businesses have low awareness and less perceived the importance of strategic management plans within their companies. Further, family businesses are considered less professional because of limited numbers of family members with professional management backgrounds and competencies as well as less contingency planning for survivability. By considering these factors, family businesses are often associated with low family involvement, lack of governance and management formalisation policy.

Method

Data and sample

Data is obtained from the STEP-KPMG report on ‘Global family business report: COVID-19 edition, Country benchmarking data – Malaysia’. A survey was conducted in five regions, including the Middle East and Africa, the Americas, Europe, Asia Pacific, and Malaysia. A total of 2,422 family business leaders in these regions from various countries had completed the survey.

The inherent institutional and market differences between the family businesses studied here result from the aggregation of results into five regions: the Middle East and Africa, the Americas, Europe, Asia Pacific, and Malaysia. The consideration of a relationship between organisational family characteristics and family business sustainability is to identify the implication of COVID-19 conditions towards the patterns that influence family business response and thus determine the organisation’s sustainability.

Given the research aims and the characteristics of the data, content analysis and review of previous literature were used to seek the structure of conditions leading to a different form of response for crisis management that indicate the level of motivation for family business sustainability. This study approach is twofold: first, calibration of the questionnaire survey of the STEP-KPMG reports into its specific category; second, the level of response is then assessed based on the benchmarking measurements with a review of previous literature. A conceptual model of this study is inspired by the outcomes of STEP-KPMG Report 2020 through the research approach. Table 1 presents a cumulative number of family businesses participated in the survey.

Source: STEP Project Global Consortium and KPMG Private Enterprise Global family business report: COVID-19 edition

Constructs and variables

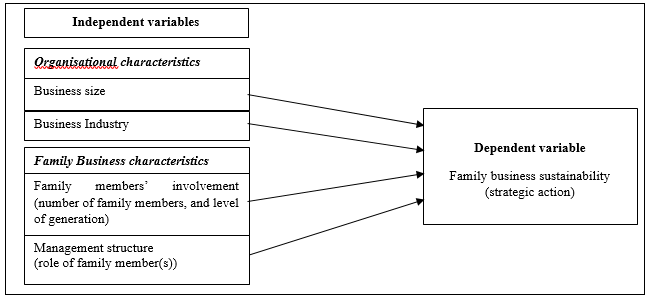

The independent variables calibrated into conditions categorised in two groups which cover

- organisational characteristics

- family business characteristics

The dependent variable is identified as the outcome of family business sustainability in terms of strategic action taken. Table 2 describes the conditions and outcomes.

Research model

We developed the model by conceptualising the factors that affect the family businesses in Malaysia and comparing them with other participating countries, as stated earlier. The model in this study relates family business characteristics, members’ involvement (generations and succession plans) and organisational characteristics (size and industry) and then links these variables with family business sustainability. The conceptual model of this study is illustrated in Figure 1.

Industry of family businesses

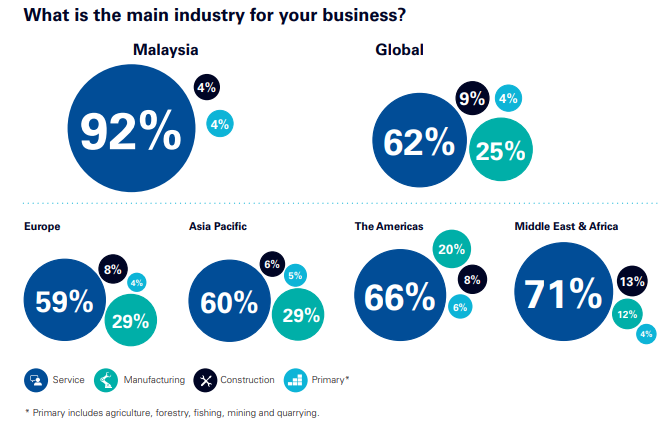

Figure 2 summarises the types of industry of family businesses that have participated in the survey, which is a total of 2,943 respondents. There are four main industries in which these businesses are actively involved including service, manufacturing, construction and primary sector (such as agriculture, forestry, fishing, mining and quarrying). A benchmarking level is presented by (a) at the global level, and (b) grouping the respondents according to their countries. Globally, the data shows that family businesses contribute significantly towards the global economy GDP at 62%. This data indicates that family businesses are important as other non-family businesses, and thus the need to ensure these businesses continuously survive in the world is crucial. Along with this view, previous studies such as Oudah et al. (2018) contended that family businesses are the backbone of economic growth in many countries, including developing countries. These family businesses play a significant role in the national economic development and sustainability globally through wealth creation, employment opportunities and economic stability.

Through the comparative benchmarking analysis, the prevailing family businesses are actively involved in the servicing industry. At the country level, Malaysia has the highest rate of family businesses in the servicing industry, at 92%, followed by Middle East & Africa at 71%, the Americas at 66%, Asia Pacific at 60%, and lastly Europe at 59%. Figure 2 also reveals a large variation of family businesses in the servicing industry in Malaysia compared to other countries. This data shows that family businesses in Malaysia in the servicing industry are important, and the failure of these companies to survive can affect the entrepreneurial activity. On the other hand, for the construction industry and primary industry, the level of family businesses is at a small percentage of 4%, respectively. In addition, it is also found that the number of family businesses involved in manufacturing is trivial.

As for other countries, similarly, the majority of the family businesses are in the servicing industry, followed by manufacturing, construction and finally, primary industry. Here, it can be seen that both the servicing and manufacturing sectors in these countries represent a significant contribution to the global economic performance. One reason for this circumstance can be due to the demand for consumer products that facilitates their necessities in life, such as food, entertainment and lifestyles.

Figure 2 also indicates that the involvement of family businesses in Malaysia can be explained by the ethnicity of families involved in a certain industry. As Malaysia is widely known for its multi-ethnicity population, this variable can explain the large percentage of family businesses in the servicing industry. According to Mosbah et al. (2017), a number of family businesses are predominated by Chinese ethnicity. Nevertheless, the Malay ethnicity or Bumiputera has increasingly contributed to the percentage of family businesses through the Malaysian government initiatives and economic policy.

Source: STEP Project Global Consortium and KPMG Private Enterprise Global family business report: COVID-19 edition

Size of family businesses

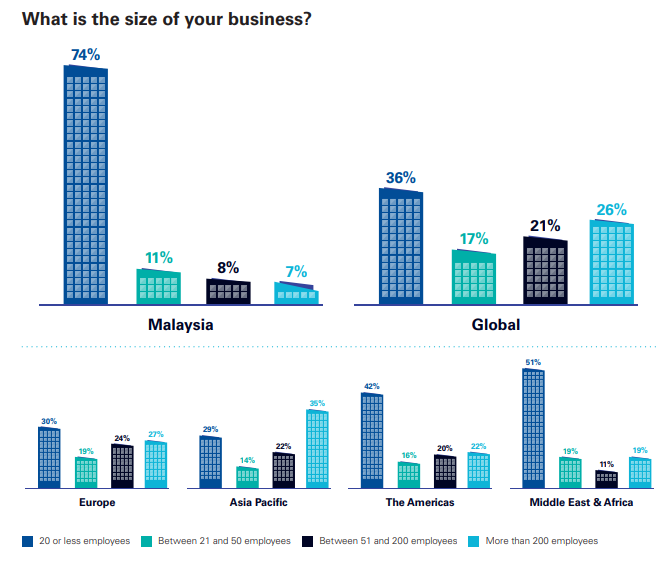

Figure 3 presents the size of family businesses that are categorised by the number of employees. According to Oudah et al. (2018), the size of family businesses is one of the critical success factors to ensure the family members’ involvement in the businesses, and can explain the potential of passing the business to the next generation from the co-founder. Medium to large family businesses are often identified as a company that will transfer the whole business to their second generation or third generation.

Based on the data shown in Figure 2 beforehand, globally, a small family business size, which comprises 20 or fewer employees, indicates the highest percentage, which is at 36%. These findings can be due to the fact that small family enterprises have less stringent regulations for their establishment, and this also can be due to business life at an early stage by its co-founder. Further, the small size of a small family business is favourable due to the rate of entrepreneurs perceived on the opportunities during its’ establishment.

Following the small size of family businesses, 26% of the family businesses surveyed are large enterprises that consist of more than 200 or more employees. This was followed by medium-size enterprises at 21%, with 51 to 200 employees, and finally, small enterprises at 17%, consisting of 21 to 50 employees.

As for Malaysia, small family businesses with fewer than 20 employees indicate the highest percentage (74%) compared to other regions. This is followed by the Middle East and African countries which is at 51%, the Americas at 42%, Europe at 30%, and lastly the Asia Pacific at 29%. Meanwhile, for large family businesses with more than 200 employees, Asia Pacific indicates the highest percentage at 35%, followed by Europe at 27%, the Americas at 22%, the Middle East and Africa at 19%, and Malaysia at 7%. This data shows that the growth of countries’ economies and capital markets can influence the number of family businesses sizes. In this view, a study by Ahmed and Uddin (2018) contended that the political economy of a country in the form of its stability, governance, business structures and framework, as well as culture, can influence the size of family businesses to be established. Therefore, this current study found that besides the internal factors of a family business, the external business settings also play important roles in determining the number of small, medium and large family businesses. Thus, as for Malaysia, the small percentage of large family businesses can be explained by the interaction between these factors encouraging family businesses to adopt their business strategies. For example, the corporate governance or company guidelines for large family businesses differentiate the structural predisposition from the small and medium family businesses.

Source: STEP Project Global Consortium and KPMG Private Enterprise Global family business report: COVID-19 edition

Generation involved in family businesses

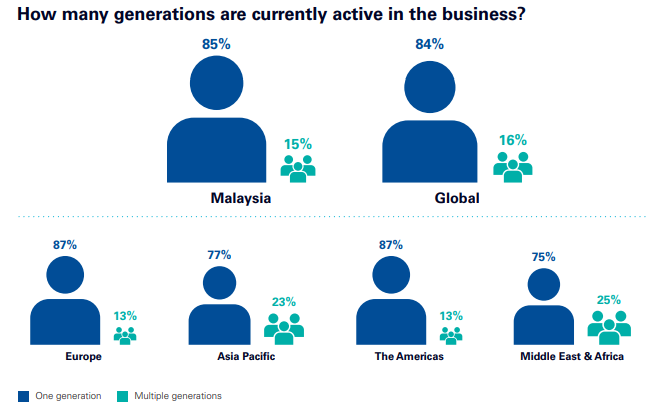

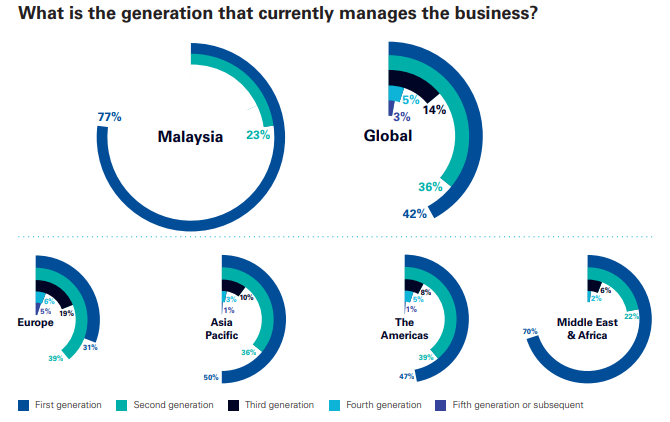

The data collected found that the majority of the family businesses are predominant by first-level generation (see figure 4). The average percentage globally indicates 84% of these family businesses are predominated by the first generation, while only 16% of the family businesses include several levels of generations’ involvement in their organisations. In Malaysia, 85% of the family businesses are managed by the first generation, while 15% are managed by multiple generations.

These findings reveal that the majority of the family businesses owners could have different ideas or approaches to getting their family members involved in the organisations’ management. In this view, the business owners believe that the decisions are best made when there is no personal interest (i.e., the family members) entangled in the decision process. Nevertheless, those who believe that multiple generations should be involved in the organisations’ management and operations activities indicate that they are open to having more comprehensive ideas, knowledge, and skills from the family members. According to Cho et al. (2017), the multiple generations of family members involved in a business is one of the critical success factors to ensure business continuity. However, some family businesses are unlikely to continue their operation for several generations due to poor succession planning. The succession plans include training and coaching, and financial and investment knowledge.

Figure 5 presents the level of generation involved in the family businesses dominated by the first level generation. At a global level, the first generation indicates 42% of the family businesses, followed by 36% for the second generation, 14% for the third generation, 5% for the fourth generation, and finally 3% for the fifth generation. This finding shows that less than 20% of the total generation are able to pass their businesses to the third generation onwards. Surprisingly, in Malaysia, there are only two generations involved in the businesses. The first generation shows the highest percentage, which is 77%, and only 22% represents the second generation. On the contrary, other countries such as Europe (5%), Asia Pacific (1%) and the Americas (1%) have a trivial but not significant percentage of fifth-generation involvement in the family businesses. As for the Middle East and Africa, the findings show that the level of family generation supporting the businesses is up to the fourth generation (2%).

Source: STEP Project Global Consortium and KPMG Private Enterprise Global family business report: COVID-19 edition

Source: STEP Project Global Consortium and KPMG Private Enterprise Global family business report: COVID-19 edition

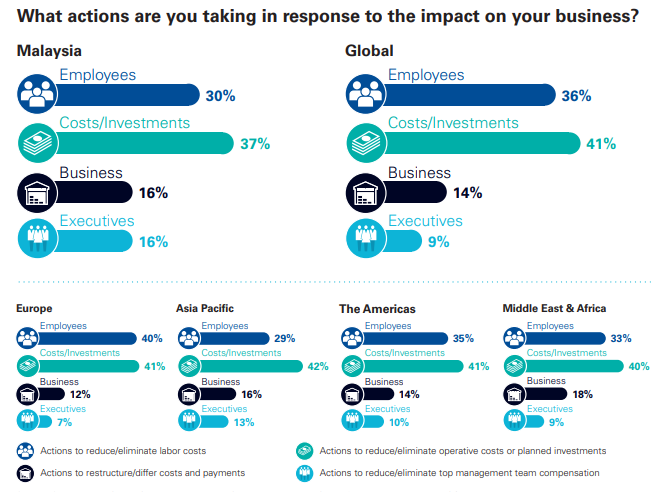

Strategic management plan for business sustainability

In an economic context, the sustainability of a family business relies on the effectiveness of the strategic plan of its owners. A strategic plan, also known as strategic management, is an organisation’s focus to ensure the owners or the shareholders adopt an effective strategy to compromise and maintain their status quo. Given this study is during the COVID-19 pandemic setting, Figure 6 presents the immediate action taken by these family businesses. There are four immediate response strategies which include (a) reduce or eliminate labour costs, (b) reduce or eliminate operative costs or planned investments (c) restructure/defer costs and payments, and (d) reduce or eliminate top management team compensation. From a global perspective, the most immediate action taken by these family businesses in the survey is to reduce or eliminate the costs or planned investments, which is at 41%. Second, the family businesses chose to reduce or eliminate labour costs (36%), and later to restructure/defer costs and payments, and reduce or eliminate top management team compensation, which is at 14% and 9%, respectively.

In Malaysia, the majority of family businesses have chosen to reduce or eliminate operative costs or planned investments, which is at 37% in total. The reduction in costs is more on cutting office expenses rather than eliminating planned investments. The second strategy which these organisations use is through reduction of labour costs. This decision is mainly freezing all hiring employees, while other countries such as Europe and the Americas chose to move all or some employees to remote status. On the other hand, the Middle East and Africa chose to reduce the employees’ pay.

As for restructure/differ costs and payments, and reducing/eliminating top management compensations, both actions are at 16%. The choice of these actions is quite similar with other countries (i.e., Europe, Asia Pacific, the Americas and the Middle East and Africa). In terms of restructured/differing costs and payments, Malaysian family businesses have delayed their payment to all or parts of their vendors’ bills and loans obligations. Unlike Europe, the Middle East, and Africa, these countries chose to renegotiate vendor contracts. As for reducing/eliminating top management compensations, all family businesses in the survey decided to defer or reduce their executive pay.

Several possible reasons can explain the decision. First, by looking at the earlier findings, many family businesses are small and medium companies, which comprise 20 to 50 employees. The size of the companies indicates that the family businesses have low financial strength. Second, the number of family members involved in the businesses can be the stumbling block for siblings or intergenerational rivalry for succession. Third, family businesses, particularly in Malaysia, lack guidance or framework and a crisis strategic management plan for managing, assessing, and planning their companies’ survival or business continuity. In addition, external factors such as government initiatives or financial assistance during the pandemic could be insufficient or be delayed due to bureaucratic processes.

Source: STEP Project Global Consortium and KPMG Private Enterprise Global family business report: COVID-19 edition

Conclusions and contributions

This paper presents the analysis of the findings from 2,422 participants of leaders in family businesses that led to a number of key insights. Based on the key results and discussion presented beforehand, in order to answer RQ1, it is suggested that the involvement of family generations is vital in defining and reshaping the family business directions as well as its strategic decision. Involvement of the family members has a positive difference in the company risk management, succession planning as well as contingency plans in their strategic planning, compared to those just acknowledging the family members’ presence. The results and discussion also suggest that intergenerational families can contribute to the performance of the firms because of family members’ education, training and work experience outside of the firm, as well as the entrepreneurship motivations to join the family business. This is also evidenced in the key results, which show that family firms with the third level of generations are able to continue their business operations given in an economic crisis, such as in Europe and other Asia Pacific countries.

In terms of RQ2, analysis from the report suggest that the essential pillars for the firms to continue functioning and moving to survive in the economy are (a) family and corporate governance, (b) strategic management planning by family members, and (c) financial and wealth planning.

Family and corporate governance are regarded as fundamental for a family business to determine the substantial structure of the company’s system, both within the family constitution and companies’ stewardship. Ideally, in the sphere of the family business model, it is proposed to integrate the family constitutions next to organisational factors, i.e., the environment as expected by the global society and sector activity. Findings from the report reveal that almost all family businesses in Malaysia lack a governance structure policy in place. Given the majority of the family businesses in Malaysia are in a small to medium scale of business, one can argue that these family businesses could have ignored the business governance policy. In addition, family businesses in Malaysia are predominant by the first level generation, which often caused less special roles from other family members in making decisions, authorisation and surveillance on the business operations.

The implication for lack of governance structure can affect the internal management and conflict between family members and business operation. In particular, during a crisis, the decision on business activities, and remedial action to be taken are the biggest challenges for these family businesses. Based on the findings, family industry, size and family generation involvement can be the contributing factors in determining the family businesses’ attitude towards systematic governance within the organisation. Without a systematic governance structure in place, the family business tends to be reluctant to plan for contingent situations, and get family members’ commitment in the planning and decision-making process. Perhaps profound and significant damage can lead to a higher loss in terms of operating costs and/or planned investment. In other words, this can be the greatest threat that is often associated with the long-term business shutdown.

Executives or family members involved in the family business with an appropriate governance structure and family constitution are more systematic. A strong governance structure in family businesses can facilitate these managers, exposing them to vast expertise training, leadership programmes, and financial knowledge updates. The provision of corporate governance in a family business can warrant a mature family business in the case of managing the family business, wealth and better lifestyle to a strategy that the family owners can build for a successful formula.

Strategic management planning is essential to ensure the family firm’s continuous resilience to adapt to the changes in the business and economic setting. More resilient family businesses are able to anticipate, respond and mitigate the risks and threats through efficient and effective strategic management planning. In addition, risk management planning is absent in the Malaysian family business. With good risk management planning, it is expected that the family business in Malaysia will prepare themselves with available alternatives and may face any challenges in a controllable manner.

Family businesses would also be able to strategise various approaches in business activities, such as product innovation, market expansion, and pricing strategies through various government support. Given Malaysia is an emerging country, family firms also are expected to establish strong networking through cross-border business communities. The family firms should seize the opportunities to strengthen their capabilities by seizing various government incentives, particularly cross-border business transactions.

In order to ensure its survival and sustainability, it is important for family businesses in Malaysia to embed in their business a strategic management plan for business growth, focusing specifically on diversification strategies and employees’ empowerment. Business longevity should be handed over to more generations despite only the second generation reported above. Based on the STEM/KPMG output, Malaysia scores the highest 74% of family businesses having 20 or fewer employees in the family business, 11% is in operation with the number of employees ranging between 21 to 50. In comparison, only 8% of family businesses have between 51 to 200 employees, and the remaining 7% have more than 200 employees in their support system. Based on this information, the Malaysian family business should be taking a more serious note to strategically manage the 74% of family business owners to have a wiser form of diversification strategies as well as increase the ideal number of employees to ensure the business can run smoothly for a longer period.

Finally, financial and estate planning are crucial for family businesses. Preserving their financial wealth is important to ensure business continuity. According to Stieglitz et al. (2016), the ability to plan for business continuity, particularly to preserve the business health and wealth position, would significantly impact business sustainability. A business that frequently changes or seldom changes or revises its persevering strategy is likely to face financial hazards during a crisis situation. The longer the crisis lasts, the lesser the financial resources become. One should remember that family businesses are bound with their socioemotional wealth nature, and protecting their assets and legacy is important to reflect the family businesses’ typical long-term orientation.

This study proposes a model in Figure 7 for all family businesses, particularly in Malaysia, to continue to survive and grow in the market. This model shall facilitate the family businesses to encounter the complexity of family and business matters. This will also help strengthen the family businesses’ financial management, being more independent and not only rely on government or other financial aid and support in order for survival and continuity of their businesses.

For future research in family business management, this paper suggests investigating family businesses’ understanding and knowledge on the implementation of strategic management and plans, their preparation for future plans, their underlying mechanisms and procedures when coping with hazard conditions. Further, investigating the family businesses related to the decision-making process and mechanisms utilised in various situations would also provide a better insight. Figure 7 presents a business strategy framework developed from this current study.

Given that this paper took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of participants responding is quite limited due to technology constraints such as internet bandwidth and coverage. Nevertheless, it is not possible to make conclusions about the family business preparedness strategies in a crisis.

References

Ahmed, S., & Uddin, S. (2018). Toward a political economy of corporate governance change and stability in family business groups: A morphogenetic approach. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 31(8), 1-27.

Arrondo-García, R., C. Fernández-Méndez, & S. Menéndez-Requejo. (2016). The growth and performance of family businesses during the global financial crisis: The role of the generation in control. Journal of family business strategy, 7(4), 227-237.

Arteaga, R., & Escribá-Esteve, A. (2020). Heterogeneity in family firms: Contextualising the adoption of family governance mechanisms. Journal of Family Business Management, 11(2), 1-23.

Baker, S. R., Bloom, N., Davis, S. J., & Terry, S. J. (2020). COVID-induced economic uncertainty National Bureau of Economic Research. Working Paper (26983).

Bhatt, R. R., & S. Bhattacharya. (2015). Do board characteristics impact firm performance? An agency and resource dependency theory perspective. Asia-Pacific Journal of Management Research and Innovation, 11(4), 274-287.

Bövers, J., & Hoon, C. (2021). Surviving disruptive change: The role of history in aligning strategy and identity in family businesses. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 12(4), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2020.100391

Boyd, B., Royer, S., Pei, R., & Zhang, X. (2015). Knowledge transfer in family business successions: Implications of knowledge types and transaction atmospheres. Journal of Family Business Management, 5(1), 17-37.

Brundtland, G. H. (1987). Brundtland report. Our common future. Comissão Mundial, 4(1), 17-25. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf

CHO, N. M., Okuboyejo, S., & Dickson, N. (2017). Factors Affecting the Sustainability of Family Businesses in Cameroon: An Empirical Study in Northwest and Southwest Regions of Cameroon. Journal of Entrepreneurship: Research and Practice, 2017(2017), 1-19. http://ibimapublishing.com/articles/JERP/2017/658737/

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., & Bergiel, E. B. (2009). An agency theoretic analysis of the professionalized family firm. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 33(2), 355-372.

Claessens, S., & Fan, J. P. (2002). Corporate governance in Asia: A survey. International Review of finance, 3(2), 71-103. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.386481

Davis, P. S., & Harveston, P. D. (1998). The influence of family on the family business succession process: A multi-generational perspective. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 22(3), 31-53. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879802200302

Diaz-Moriana, V., Hogan, T., Clinton, E., & Brophy, M. (2019). Defining family business: A closer look at definitional heterogeneity. In The Palgrave handbook of heterogeneity among family firms (pp. 333-374). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

Evert, R. E., Sears, J. B., Martin, J. A., & Payne, G. T. (2018). Family ownership and family involvement as antecedents of strategic action: A longitudinal study of initial international entry. Journal of Business Research, 84, 301-311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.07.019

Faghfouri, P., Kraiczy, N. D., Hack, A., & Kellermanns, F. W. (2015). Ready for a crisis? How supervisory boards affect the formalized crisis procedures of small and medium-sized family firms in Germany. Review of Managerial Science, 9(2), 317-338.

Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Haynes, K. T., Núñez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K. J., & Moyano-Fuentes, J. (2007). Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Administrative science quarterly, 52(1), 106-137.

Harrington, L. M. B. (2016). Sustainability theory and conceptual considerations: a review of key ideas for sustainability, and the rural context. Papers in Applied Geography, 2(4), 365-382. https://doi.org/10.1080/23754931.2016.1239222

Ibrahim, H., & Samad, F. A. (2010). Family business in emerging markets: The case of Malaysia. African Journal of Business Management, 4(13), 2586-2595.

Kelly, L. M., Athanassiou, N., & Crittenden, W. F. (2000). Founder centrality and strategic behavior in the family-owned firm. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 25(2), 27-42. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225870002500202

Klein, S. B. (2000). Family businesses in Germany: Significance and structure. Family Business Review, 13(3), 157-182.

La Porta, R., Lopez‐de‐Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (1999). Corporate ownership around the world. The journal of finance, 54(2), 471-517.

Lee, J. (2006). Family firm performance: Further evidence. Family business review, 19(2), 103-114. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2006.00060.x

Leotta, A., Rizza, C., & Ruggeri, D. (2017). Management accounting and leadership construction in family firms. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 14(2), 1-21, https://doi.org/10.1108/QRAM-09-2015-0079

Littunen, H., & Hyrsky, K. (2000). The early entrepreneurial stage in Finnish family and nonfamily firms. Family Business Review, 13(1), 41-53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2000.00041.x

Martínez, J. I., Stöhr, B. S., & Quiroga, B. F. (2007). Family Ownership and Firm Performance: Evidence From Public Companies in Chile. 20(2), 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2007.00087.x

Md Zaini, S., Sharma, U., Samkin, G., & Davey, H. (2020, January). Impact of ownership structure on the level of voluntary disclosure: A study of listed family-controlled companies in Malaysia. In Accounting Forum, 44(1), 1-34. Routledge.

Melin, L., Nordqvist, M., & Sharma, P. (Eds.). (2013). The SAGE handbook of family business. Sage.

Memili, E., Fang, H. C., Koc, B., Yildirim-Öktem, Ö., & Sonmez, S. (2018). Sustainability practices of family firms: The interplay between family ownership and long-term orientation. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(1), 9-28.

Minichilli, A., Brogi, M., & Calabrò, A. (2016). Weathering the storm: Family ownership, governance, and performance through the financial and economic crisis. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 24(6), 552-568. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12125

Mitter, C., Duller, C., & Feldbauer-Durstmüller, B. (2012). The impact of the family’s role and involvement in management and governance on planning: evidence from Austrian medium-sized and large firms. International Journal of Business Research, 12(3), 56-68.

Mokhber, M., Tan, G. G., Rasid, A. S. Z., Vakilbashi, A., Zami, M. N., Yee, W. S (2017). Succession planning and family business performance in SMEs. Journal of Management Development, 36(3), 330–347. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-12-2015-0171

Mosbah, A., Serief, S. R., & Abd Wahab, K. (2017). Performance of family business in Malaysia. International Journal of Social Sciences Perspectives, 1(1), 20-26.

Mussolino, D., & Calabrò, A. (2014). Paternalistic leadership in family firms: Types and implications for intergenerational succession. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 5(2), 197-210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2013.09.003

Nicholson, G. J., & Kiel, G. C. (2007). Can directors impact performance? A case‐based test of three theories of corporate governance. Corporate governance: An international review, 15(4), 585-608.

Oudah, M., Jabeen, F., & Dixon, C. (2018). Determinants linked to family business sustainability in the UAE: An AHP approach. Sustainability, 10(1), 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010246

Porfírio, J. A., Felício, J. A., & Carrilho, T. (2020). Family business succession: Analysis of the drivers of success based on entrepreneurship theory. Journal of Business Research, 115, 250-257.

Pyromalis, V. D., & Vozikis, G. S. (2009). Mapping the successful succession process in family firms: evidence from Greece. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 5(4), 439-460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-009-0118-3

Rodrigo, L. (2015). A Holistic Perspective on Corporate Sustainability Drivers. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 22(1), 32–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1325

Sciascia, S., & Mazzola, P. (2008). Family involvement in ownership and management: Exploring nonlinear effects on performance. Family Business Review, 21(4), 331-345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2008.00133.x

Stamm, I., & Lubinski, C. (2011). Crossroads of family business research and firm demography—A critical assessment of family business survival rates. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 2(3), 117-127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2011.07.002

Stewart, A., & Hitt, M. A. (2012). Why can’ta family business be more like a nonfamily business? Modes of professionalization in family firms. Family Business Review, 25(1), 58-86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486511421665

Stieglitz, N., Knudsen, T., & Becker, M. C. (2016). Adaptation and inertia in dynamic environments. Strategic Management Journal, 37(9), 1854-1864. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2433

Villalonga, B., & Amit, R. (2020). Family ownership. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 36(2), 241-257.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 October 2022

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-958-0

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

3

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-802

Subjects

Multidisciplinary sciences, sustainable development goals (SDG), urbanisation

Cite this article as:

Md Zaini, S., Ahmad Noruddin, N. A., Yusof, M., & Mohd Nor, L. (2022). Fostering Family Business Sustainability Strategies During Covid-19 Pandemic. In H. H. Kamaruddin, T. D. N. M. Kamaruddin, T. D. N. S. Yaacob, M. A. M. Kamal, & K. F. Ne'matullah (Eds.), Reimagining Resilient Sustainability: An Integrated Effort in Research, Practices & Education, vol 3. European Proceedings of Multidisciplinary Sciences (pp. 731-750). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epms.2022.10.69