Abstract

Power is associated with men and the world of men is recognized as the world of power. Friendship and cooperation are, however, connected to women and their world. In general, there has always been a state of a power imbalance between men and women. Besides gender, high occupational status gives people the autonomy to exert power. Considering gender and status as two parameters that assist power demonstration, this qualitative study attempts to explore the factors influencing men and women’s cooperation in gender studies. We aim to find out whether power, status and friendship has any impacts on both genders’ decision-making process to contribute to research activities. The data of this study is based on men and women’s confirmation or refusal to take part in research on gender studies. Findings of the study suggest that factors such as gender, power relations and occupational status of the participants determine their willingness to cooperate in studies pertaining to gender. In equal occupational status, the gender of the participants creates power and affects the cooperation of the participants. Moreover, it is found that the concept of, due to its sensitive nature, is a determining factor in the participants’ decision making to accept or refuse to cooperate.

Keywords: Power relations, gender, friendship, cooperation, social status, decision making

Introduction

In the process of research, finding suitable participants who are willing to cooperate is a daunting challenging task for the researchers in various fields specifically gender. Since men and women have different characters and behave differently in society, they adopt various attitudes when they are asked to cooperate in an activity or act as participants in a study.

According to some studies, men are connected to masculinity and masculinity generates power (Kaufman, 2000) while women, on the other hand, are into establishing their friendship and cooperating with one another (Capraro, 2018; Coates, 2015; Greif, 2008). This can be due to the asymmetries that exist between men and women in a society where asymmetries lead to power and symmetries to solidarity (Brown & Gilman, 1960). In general, men and women’s tendencies to cooperation and power can affect the way they accept or refuse to cooperate with others. This study attempts to look at the factors that influence women and men’s cooperation and power demonstration attitudes to take part in gender studies. The present research, examining those factors, provides an insight based on the researchers’ own observation working with different genders during several years of research.

Gender, Cooperation and Power relations

In the context of society, gender creates either power or powerlessness. For a long time, feminist theories considered power as the core element in men’s world (Edley, 2017). Also, Kaufman (2000) believes that masculinity is coupled with power and men consider power as an opportunity to have control over the others in various social settings. Moreover, a person who is capable of taking advantage of inequalities between people in society is regarded as a powerful person. Black and Coward (1998) suggest that power is better described in terms of ideology. They believe that this dominating behaviour is taken over from society and can be considered as a socially structured heritance to men and women as well. This demonstrates that power discrimination in which a powerful party controls a weak party is created by society and its norms. In society, women are associated with cooperation and support because they generally value and appreciate friendship (Coates, 2015; Greif, 2008). This can also be explained through the norms in which societies and the surroundings have created for women.

These socially constructed differences between men and women have influenced them in various domains. For instance, in an interactional level, the way men and women interact is different based on the powerful and cooperative roles that they play in society. The language that men use has the elements of power demonstration and dominance while the language that women use encourages cooperation and support (Coates, 2015).

In research activities, it is observed that male and female participants are significantly different in cooperating. In a conducted study, female participants tend to cooperate and collaborate more than male participants (Stockard, Van De Kragt, & Dodge, 1988). In another study, whereby the participants had to donate some cash to anonymous partners, it appears that women had more tendencies than men to cooperate. They donate two times more than their male counterparts (Eckel & Grossman, 1998). Eckel and Grossman (1998) have also classified men’s resistance to donate voluntarily as selfish behaviour which is less observed among female participants. It can be generally inferred that women are more cooperative than men in that sense. Men, on the other hand, are inclined to cooperate differently due to the masculinity. It is found in a study that men behave based on their mating strategies while receiving help request from women (Schwarz & Baßfeld, 2019). Moreover, men prefer competing with others (Cameron, 2011). When competition is involved, they actively cooperate with the other people while for female participants competition does not make a significant difference in their cooperative manner (Van Vugt, De Cremer, & Janessen, 2007).

The cooperative attitude of people can fluctuate when they correspond to different genders. In other words, the gender of the people who are communicating with each other affects the extent in which cooperation is achieved among them. For instance, in a study by Kerr and MacCoun (1985), the participants show less cooperation when their partner is a man.

Fowler (1985) believes that besides gender, the social norms which are practised in different societies can distribute either power or cooperation among people. In this regard, Brown and Gilman (1960) assert that power prevails in an asymmetrical and nonreciprocal relation where one is in an upper position such as doctor-patient (West, 2011) and teacher-student’s relationship (Abdullah & Hosseini, 2012). Being in an upper position creates autonomy and that is the reason that in asymmetrical professional situations the powerful party imposes power and dominance over the weaker party. In the same vein, Leet-Pellegrini (2014) finds that gender cannot be the only effective factor in the interactants’ powerful manner. In fact, gender and expertise level of the communicators give people the opportunity to exert power more than cooperation. This is approved in another study by O’Barr and Atkins (2011) where they argue that the social status of the participants overrides their gender in exerting power. Woods (1989), however, has found the opposite. She has examined the relation between power and occupational status among male and female colleagues at workplace. Based on her findings, she concludes that gender is more effective than the status of the participants in exerting power. She has evidenced that even men in lower professional positions show powerful attitudes when communicating with their female colleagues who are higher in occupational status than them.

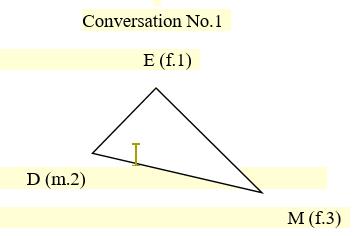

Woods (1989) in her study has used a triangular shape in order to show hierarchical levels of occupational status among the participants in each conversation. In her triangular shape (Figure 1), each angle demonstrates the participants’ professional standings compared to the other participants in the same group.

Source: (Woods, 1989, p. 148)

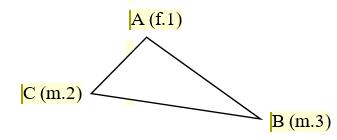

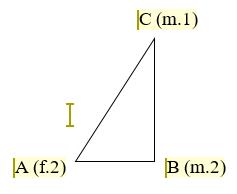

In this study, her triangular model has been adopted and modified to fit the purpose of the study. This model is applied in our study in order to demonstrate asymmetrical relations such as friendship and professional standings (see Figures 2 and 3). However, in Woods’ model (1989) each angle represents an individual while in our study each angle presents a group.

Problem Statement

The researchers of the present study, as female researchers, have worked with both men and women in language and gender domain for many years. It is observed that some people cooperate and respond positively or voluntarily to participate in research on gender studies while some refrain from being included in the studies. The researchers have been prompted to conduct this study in order to investigate what factors can influence men and women’s decision making to cooperate or not to cooperate in research on gender studies.

Research Questions

- What are the factors influencing women and men’s willingness to cooperate and participate in research on gender studies?

- Do women and men cooperate differently in research on gender studies?

- Are women more cooperative than men in taking part in research on gender studies?

Purpose of the Study

Since gender studies are growing rapidly in various domains, it is crucial to find out the factors which influence women and men’s willingness to take part in studies where gender is a central element. The main purpose of this study is to find out the factors that influence women and men’s decision to accept to cooperate in research on gender studies or refuse to be a part of it. This study also looks at gender research as a determining factor in women and men’s decision making and collaboration. Consequently, we will find out which groups of respondents, female or male, are more cooperative to be a part of gender research.

Research Methods

The profiles of male and female participants who have cooperated or declined to cooperate in our research on gender studies have been chosen to be the base of this study’s data. The data consist of 8 male and 8 female participants in addition to 6 ‘potential’ participants. The term ‘potential’ is used to refer to the subjects who were asked to participate in the gender studies research, but they declined to cooperate. This study uses the term ‘potential’ to differentiate the subjects who refused to take part in our study from the participants who actually contributed. All the participants and potential participants are Iranians and are acquainted with the researchers through different channels. Moreover, their friendship degrees with the researchers vary. The profiles of the participants and the potential participants are illustrated in tables 1, 2 and 3 with respect to their gender, occupational status, relationship with the researchers and duration of their friendship. Therefore, the analysis is based on the comparison between these elements. The names of the participants are deleted, and an alphabetic letter presents each group. Each group’s alphabetic letter which is accompanied by a number is used to present each individual participant. For instance, the participants in group 1 are identified by the letter ‘A’. There are eight participants in this group which are identified as A1, A2, A3 and alike.

In the following section, the profile of the participants is divided into two distinct parts. The first part deals with the participants who accepted to join the gender studies research and the second section covers the profile of the potential participants who refused to take part.

The Profile of the Female and Male Participants

The first table, Table 1, belongs to the female participants and the next table, Table 2, belongs to the male participants who cooperated. Table 1 shows that female participants are the researchers’ colleagues and friends. They know each other for 8 years except A8. They are all English instructors in the language centre in which the researchers were working at the time of the research. As such, the occupational status of the participants and the researchers are at the same level.

As can be seen in Table 2, the male participants are the researchers’ students and know them for less than a year. As for the occupational status of the male participants, it appears that some of them possess higher occupational status compared to the other participants and the researchers who are English instructors.

The Profile of the Potential Male Participants

Table 3 demonstrates the profile of the potential male participants who were approached by the researchers and asked to take part in the research on gender studies but they all refused to cooperate. The potential male participants who were not willing to take part are the researchers’ colleagues. As a result, their occupational status is the same. Besides being colleagues, the potential participants and the researchers are all friends and know each other for 3 years except C5 who knows the researchers for a period of 2 years.

Findings

In the following sections, this study explains and presents a comparison between the profiles of these three groups. The comparison is done in two separate sections. The first section is devoted to gender and the group members’ acquaintance with the researchers. The second section indicates gender and the group members’ occupational status with respect to the researchers. Through this comparison, this research hopes to investigate the factors influencing the participants’ cooperation in gender studies.

Friendship with the Researchers

A comparison between the profiles of the groups shows that the female participants and the potential male participants are the researchers’ colleagues and friends while the male participants who accepted to take part are the researchers’ students. The comparison also reveals that the female participants know the researchers for a longer time than all the other participants. However, the male participants who participated in gender studies know the researchers for a much shorter period of time than the potential male participants who refrained from taking part.

The level of friendship with the researchers among the groups is demonstrated in a graphic triangle adopted and modified from Woods (1989). Fig. 2 shows that the female participants have the highest level of friendship with the researchers, followed by the potential male participants and the male participants respectively.

Occupational Status among the groups

In terms of occupational status, it appears that the females and the potential male participants possess the same occupational level. They are all English language instructors. Nevertheless, the male participants, who accepted to take part, possess different occupational status and in some cases, they have high-status positions (see Table 3). Fig. 3 shows that the occupational status of the males who participated is higher than the rest

As stated earlier, the researchers are both English instructors. The female participants and the potential male participants are all English instructors as well. Therefore, they all hold the same occupational status.

The findings indicate that there are three contributing factors that influence the participants’ decision to either take part in the research on gender studies or refrain from participating. These three factors are gender, friendship and power imbalance. In addition to these factors, there is one more determining aspect in the process of decision making and that is the type of study they are asked to participate in. It appears that gender studies also play a role in the participants’ decision-making process. In the following section, friendship and power are explained concerning gender. Afterwards, the effect of gender studies will be explained independently.

Friendship and Gender

There is a long-term friendship between the female participants and the researchers (see Table 1). The female participants accepted to be a part of research on gender study without any hesitation in order to support and collaborate. This can be explained by the notion that women care about friendship and cooperation with their friends (Coates, 2015). Their friendship with the researchers, who are females, motivated them to cooperate with them.

The findings also show that friendship is not very significant for men and this is not a determining factor for them in accepting or refusing to be included in research. For instance, the potential male participants who refused to be included in research on gender studies are the researchers’ friends and colleagues. They know the researchers for almost 3 years. Despite their friendship with the female researchers, they do not show their willingness to cooperate. On the other hand, the male participants who accepted to cooperate are the researchers’ students who know them for less than a year. As such, there was no established friendship between them except the teacher-student relationship. As a result, it is inferred that friendship is important for women while it does not play a significant role for men in this study. Moreover, the gender of the researchers may have a different effect on male friendship than on female friendship. In a study by Vial, Brescoll, Napier, Dovidio, and Tyler, (2018), the authors discovered that women and men follow a pattern which is consistent with gender in-group favouritism. It shows that women favour women and men favour men and that can be an explanation of why women in the present study are more cooperative towards the researchers who are female as well. However, since men are connected to power (Kaufman, 2000), we need to analyse their behaviour through power perspective in the following section.

Power and Gender

The study in hand is looking at power imbalance between the groups and the researchers to investigate the factors which resulted in asymmetry since asymmetrical situations generate power (Brown & Gilman, 1960). The analysis reveals that the female participants are at the same occupational level as the researchers. They are all English language instructors in the language centre. They all agreed to cooperate with the researchers and participate in research on gender studies. There is no specific power imbalance observed between the female participants and the researchers in terms of occupational status.

The potential male participants, who refused to take part in research on gender studies, possess the same occupational status as the researchers. Like the female group, they are all English language instructors who work with the researchers in a language centre. Despite their same professional status level with the researchers (Fig. 2), they refrain from cooperating with them. This can be explained by the virtue of the fact that men are naturally more into power demonstration than cooperation (Coates, 2015). In fact, society gives the authority to people in power to refuse or accept a request. In this study, potential male participants refused to cooperate with the researchers, who are both females, because being a man gives them the power to act dominantly over them. As such, in equal occupational positions where power is equal, gender is more effective.

The male participants, who have actually cooperated, have the highest occupational status compared to the other groups and the researchers. Although they possess higher occupational status compared to the researchers, they are the researchers’ students. Teacher-student relationship generates power imbalance whereby teachers have authority over their students (Abdullah & Hosseini, 2012; Swann, 1989; Walsh, 2008). It appears that in this study, the power imbalance between students and teachers puts the students in a lower position that cannot complain and turn down their teachers’ request to participate in their gender studies. The male students, despite their high occupational status out of classroom confinement, all agreed to cooperate with their teachers (the researchers). It shows that power imbalance between the teachers and the male participants at that particular time and place creates an atmosphere that the male participants’ higher occupational status does not count. It should be noted that the male participants were asked to cooperate in the research they were still students. Therefore, as long as they are students and they are in the classroom, the power belongs to the teacher. Moreover, the power imbalance in teacher-student relationship overrides power imbalance between genders. It reinforces the idea that power is relative (Holmes & Stubbe, 2003) and effective at certain time and place depending on the relationship between people, occupational status, expertise level and any other relationships that create imbalance.

Gender Study

It appears that the research on gender studies, due to analysing gender, has some complications on its own accordance such as the bias which is attached to gender specifically to women’s community (Walden, 2007). before the study, all the participants and the potential participants were briefed about the research and were informed that their language is going to be analysed for research on gender studies. As for the female participants, there is no single instance of discomfort among them since they all agreed to cooperate without hesitation. However, the situation is different for men. As illustrated in Table 3, the participants who refused to cooperate in gender study research are all men. The reason lies in the fact that masculinity and power are interrelated (Kaufman, 2000) and the gendered nature of such studies can create a paradoxical situation for men where their masculinity and power are in jeopardy. Moreover, as stated earlier, the researchers in this study are females. That also generates an uncomfortable situation for them and contributes to their refusal.

Since only men refused to take part, it can be argued that men in this study have the apprehension that their masculinity is exposed to female researchers and is challenged by them. Apparently, they were not comfortable with the gendered nature of the study. As a result, they provided various reasons to refrain from cooperating despite their friendship with the researchers. The male participants who agreed to cooperate may have the same feeling about gender studies. However, they did not show any rejections since the power of their teachers (the researchers) created an authority over them that they could not resist. The male participants who take part in our research on gender studies do not want to refuse to participate because the researchers have authority over them as their teachers. As such, they ignore not only the bias attached to the gender study research but also their occupational higher positions.

Conclusion

From the analysis above, it is revealed that in this study, the attitudes that the females and males show towards research on gender studies stem back from the ways in which they communicate in society. As stated earlier, cooperation is attached to women and power is connected to men (Coates, 2015). The female participants in this study show their cooperation by participating without any hesitations. On the other hand, the male potential participants show their power by refusing to collaborate.

The gender of the participants is found to be a significant factor in our study. It creates power and at the same time generates solidarity. This ultimately results in people’s refusal or acceptance to take part in research on gender studies. The female participants accepted to contribute due to their concern about friendship and cooperation (Coates, 2015). The male participants in this study, on the other hand, have proved that power is more important for them than friendship. The potential male participants rejected to take part despite their friendship and the equal occupational status with the researchers. It appears that in equal occupational positions among men and women, gender is effective and equips men with the power to reject the request of the females. Since the participants are Iranians, this can also be explained through the Iranian men’s perception of gender and power. In Iranian society, simply being a man grants them the autonomy to be powerful and superior to women (Fassihian, 2001). This can affirm the reason why the potential male participants refused to take part in the research on gender studies. On the other hand, this study reaffirms that Iranian women are cooperative towards other women (Ahmadi, Afshar, & Shahabinejad, 2013).

The findings also show that masculinity makes men uncomfortable to collaborate in gender studies. On the other hand, the fact that the male students accepted to cooperate in their teachers’ gender project reinforces the idea that power is relative. The male participants show that occupational status and gender loses its power to the other power asymmetries which are more effective at a certain time and place.

It must be emphasized that this study does not claim to resolve the problems that the researchers may face in choosing the participants in gender studies. However, this adds to the growing body of experimental work on gender studies and provides some insights for future studies.

Besides, the findings yield vision for the researchers to concern about the gender of their participants and the power of the group community they are aiming at. It is sensible to consider the power relations between the researchers and the participants as well. The researchers should bear in mind that gender studies carry some bias. It is apparent that getting approval from male participants to take part in research on gender studies is a challenging task especially if the researcher is a female. This signifies that gender studies should be encouraged more in order to decrease the biased reactions against them.

References

Abdullah, F. S., & Hosseini, K. (2012). Discursive enactment of power in Iranian high school EFL classrooms. GEMA Online® Journal of Language Studies, 12(2), 375-392.

Ahmadi, Y., Afshar, J. A., & Shahabinejad, M. (2013). Status of Women’s Entrepreneurship in Iran. Journal of Human and Social Science Research, 1(2), 129-137.

Black, M., & Coward, R. (1998). Linguistic, Social and Sexual Relations: A Review of Dale Spender’s Man Made Language. In D. Cameron (Ed.), The Feminist Critique of Language: A Reader (pp. 100-118). London: Routledge.

Brown, R., & Gilman, A. (1960). The Pronouns of Power and Solidarity. In T. A. Sebeok (Ed.), Style in Language (pp. 253-276). Cambridge: M.I.T.

Cameron, D. (2011). Performing gender identity: Young men's talk and the construction of heterosexual masculinity. In J. Coates & P. Pichler (Eds.), Language and gender: A reader (2nd ed., pp. 250-262). United Kingdom: Wiley Blackwell.

Capraro, V. (2018). Women are slightly more cooperative than men (in one-shot Prisoner's dilemma games played online). arXiv preprint arXiv:1805.08046.

Coates, J. (2015). Women, Men, and Language: A Sociolinguistic Account of Gender Differences in Language (3rd ed. Reissued). Routledge.

Eckel, C. C., & Grossman, P. J. (1998). Are Women Less Selfish Than Men? Evidence From Dictator Experiments. The Economic Journal, 108, 726-735.

Edley, N. (2017). Men and masculinity: The basics. Routledge.

Fassihian, D. (2001). Break the Cycle Raise Your Sons to Respect and Admire Women. Retrieved February 27, 2012, from http://www.iranian.com/DokhiFassihian/2001/May/Men/index.html.

Fowler, R. (1985). Power. In T. A. van Dijk (Ed.), Handbook of Discourse Analysis: Discourse Analysis in Society (Vol. 4, pp. 61-83). London: Academic Press.

Greif, G. L. (2008). Buddy System: Understanding Male Friendships. USA: Oxford University Press.

Holmes, J., & Stubbe, M. (2003). Power and Politeness in the Workplace: A Sociolinguistic Analysis of Talk at Work: Longman.

Kaufman, M. (2000). Men, Feminism, and Men’s Contradictory Experiences of Power. In A. Minas (Ed.), Gender Basics: Feminist Perspectives on Women and Men (2nd ed., pp. 23-29). CA: Wadsworth.

Kerr, N., & MacCoun, R. J. (1985). Role Expectations in Social Dilemmas: Sex Roles and Task Motivation in Groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 547-1556.

Leet-Pellegrini, H. M. (2014). Conversational Dominance as a Function of Gender and Expertise. In H. Giles, P. Robinson & P. M. Smith (Eds. Revised), Language Social Psychological Perspectives (pp. 97-104). Elsevier.

O’Barr, W., & Atkins, B. K. (2011). “Women's Language” or “Powerless Language”?. In J. Coates & P. Pichler (Eds.), Language and Gender: A Reader (2nd ed., pp. 451-460). United Kingdom: Wiley Blackwell.

Schwarz, S., & Baßfeld, L. (2019). Do men help only beautiful women in social networks?. Current Psychology, 1-12.

Stockard, J., Van De Kragt, A., & Dodge, P. (1988). Gender Roles and Behavior in Social Dilemmas: Are There Sex Differences in Cooperation and in its Justification? Social Psychology Quarterly, 51(2), 154-163.

Swann, J. (1989). Talk Control: An Illustration from the Classroom of Problems in Analyzing Male Dominance of Conversation. In J. Coates & D. Cameron (Eds.), Women in Their Speech Communities (pp. 123-140). London: Longman.

Van Vugt, M., De Cremer, D., & Janessen, D. (2007). Gender Differences in Cooperation and Competition The Male-Warrior Hypothesis. Psychological Science, 18(1), 19-23.

Vial, A. C., Brescoll, V. L., Napier, J. L., Dovidio, J. F., & Tyler, T. R. (2018). Differential support for female supervisors among men and women. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(2), 215-227.

Walden, R. (2007). Gender Bias in Research. JRSM, 100(2), 66-66.

Walsh, J. (2008). The Critical Role of Discourse in Education for Democracy. Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies, 6(2), 54-76.

West, C. (2011). When the Doctor Is A "Lady": Power, Status And Gender In Physician-Patient Encounters. In J. Coates & P. Pichler (Eds.), Language and Gender: A Reader (pp. 468-482). United Kingdom: Wiley Blackwell.

Woods, N. (1989). Talking Shop: Sex and Status as Determinants of Floor Apportionment in a Work Setting. In J. Coates & D. Cameron (Eds.), Women in Their Speech Communities: New perspectives on Language and Sex (pp. 141-157). London: Longman.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

26 December 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-950-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

2

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-882

Subjects

Technology, smart cities, digital construction, industrial revolution 4.0, wellbeing & social resilience, economic resilience, environmental resilience

Cite this article as:

Mohajer*, L., & Jan, J. B. M. (2017). Gender Differences: Factors Influencing Men And Women’s Participation In Gender Research. In P. A. J. Wahid, P. I. D. A. Aziz Abdul Samad, P. D. S. Sheikh Ahmad, & A. P. D. P. Pujinda (Eds.), Carving The Future Built Environment: Environmental, Economic And Social Resilience, vol 2. European Proceedings of Multidisciplinary Sciences (pp. 786-796). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epms.2019.12.80