Abstract

The aim of the research is to find out which European rock climbing destinations are the most visited by Czech climbers and what European regions at the level NUTS1 and NUTS2 are the final destinations for this segment of sport tourism. Quantitative analysis of abroad trips of Czech climbers to the rock climbing destinations and rock climbing areas regionalized at level NUTS1 and NUTS2 was done. The data were collected from the climbing logbooks available on rock climbing web portals. Over 400 respondents were selected from more than 4,000 climbers with a registered climbing logbook, based on specific criteria. More than 2,500 trips abroad to different climbing areas in Europe were analysed during one calendar year. The most visited areas for Czech climbers at the level NUTS 1 are Bayern in Germany, Nord Est in Italy, Slovakia, Méditerranée in France, Este in Spain and in Slovenia. The most visited areas for Czech climbers at the level NUTS 2 are Oberfranken in Germany, Provincia Autobnoma diTrento in Italy, Central Slovakia in Slovakia, Western Slovenia in Slovenia and Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur in France. Hierarchy of NUTS1 and NUTS2 for statistical data processing is suitable for tourism business and economical purposes. The findings demonstrate potential of different European regions for rock climbers as a special segment of sport tourism.

Keywords: Rock climbing, tourism, sport tourism, regionalization, NUTS, climbing areas

Introduction

In sport & tourism research Weed (2014, p. 1-2) has defined major problems to solve in the next 20 years. One of his aims is to figure out, “how smaller sports tourism events or active sports tourism products provide a greater return for destinations than investment in one-off major events”. Rock climbing sport tourism can be taken as an example of how “different destinations of different sizes might benefit from developing single or multi-product sports tourism offers” (Weed, 2014, p. 1-2).

Climbing is most often publicly perceived as a sport, which is mainly about pushing human limits and overcoming technical difficulties in ascents. In terms of tourism, however, climbing can be a means for independent travels to places where climbers realize their goals. The climbers’ motivation can also be in exploring natural climbing areas, where they get in a close touch with nature, using their abilities and skills. Kulczycki (2014) dealt with relationships of mountaineers to climbing areas. Authors also investigated motivation of mountaineers when travelling (Ewert et al., 2013; Caber & Albayrak, 2016). Climbing is a sport that offers a variety of disciplines. Currently, the most common climbing is rock climbing in natural terrains and also sport climbing on artificial walls. Rock climbing terrains can be found in almost all countries all over the world. Europe has climbing regions of world significance. Climbers who travel abroad to rocky terrains are becoming an important part of tourism. Climbers become part of the local culture; they interact with the local people and use the infrastructure and services in the given region. Climbing sport tourism contributes to development of the local economy.

Problem Statement

Rock climbing sport tourism is a specific form of tourism. Rock climbers who travel abroad are outbound participants of this tourism. They travel to the selected destinations for both sport (climbing) and exploring experience. Climbers become an important economic segment in the visited region. The socio-economic regionalization of climbing areas according to European standards of NUTS enables an outbound sports tourism analysis and hierarchical comparison of the results.

Rock climbing sport tourism and lifestyle mobilities

Sport tourism has been defined by many authors. In the Dictionary of Tourism Zelenka & Pásková (2012, p. 540) have recently defined sports tourism as a "form of tourism, whose participants can be both spectators and active athletes (occasional, recreational, performance or top athletes) of various kinds of competitions, races or mass sporting events."

Lifestyle mobilities were described by Cohen, Duncan & Thulemark (2013) and Cresswell & Merriman (2011). Lifestyle rock climbing and moving of the climbers around the world was investigated by Ricky (2016, 2017). Factors affecting climbers’ motivation to visit a particular climbing destination were processed in the research of Caber & Albayrak (2016) and Ewert et al. (2013). Rickly-Boyd (2012, 2013) also focused on mobility, the climbing community and their climbing travels. Thorpe (2012) was first concerned with “transnational mobilities in snowboarding culture” and then (2014) more generally with “action sport cultures”. Albayrak and Caber (2016) took an example of climbing destination in the case of Turkish Geyikbayiri climbing area in Antalya and tried to assign the attributes of a climbing area. Frequency of sandstone towers ascents in Bohemia was investigated by Chaloupský (2014). Outbound travels of Czech climbers in European rocky areas belong to the forms of sports tourism. A widely-spread term for this specific form is a rock climbing sport tourism.

Rock climbing disciplines

Rock climbing can be defined as a climbing discipline that takes place on natural rocks. Rocks can be only a few meters high or reach heights of hundreds of meters. Rock climbing can be further divided into traditional climbing, sport climbing, aid climbing and bouldering. Traditional climbing, sport climbing and bouldering are the so called free climbing disciplines, where the rock climbers only move using the power of their own body. They are belayed by their co-climber using a rope to catch a possible fall. In traditional climbing the belaying is done by temporary protective gears. The leading climber fixes the protective gear from a climbing position and the following climber takes the gear out for the lead to be able to use it again. Differently, in sport climbing the protection aids (bolts) have been drilled and fixed into the rock for a permanent use. In the case of bouldering no rope is necessary, because climbing is performed just a few metres over the ground; if needed, the climber can jump down off the rock on the mattress which is laid under the rock. In aid climbing the climbers use special ascending devices as progressive artificial aids (hooks, cams, nuts, copperheads, ladders), which serve not only for protection, but climbers can also use them to proceed across the wall. The climbers who concern with rock climbing are simply called “climbers” for the purpose of this research.

Regions and destinations of rock climbing

For this research study it is necessary to define the system of regionalization of climbing areas in Europe. Regionalization can be understood in two basic approaches by the defining factors: physical-geographically and socio-economically. Physical-geographical conception of climbing areas distribution is particularly suitable for the definition of meso-regions, as defined for example in Germany by Goedeke (1992). A climbing guide of Europe - Sport Vertical, edited by Atchison-Jones (2002), is based on the division of states and the subsequent division into areas suitable for cartographic coverage. In the USA Toula (2003) divided rock climbing areas first according to states and then directly into specific climbing areas. For practical purposes, most climbing guides process only one particular climbing area. Smaller climbing areas use to be clustered within differently sized regions, which are defined by logical, but often vague criteria. Climbing guides also use to be processed through selections of the nicest, hardest and most enjoyable ascents and areas. It is necessary to define the regions, in order to be able to compare the results of statistical surveys.

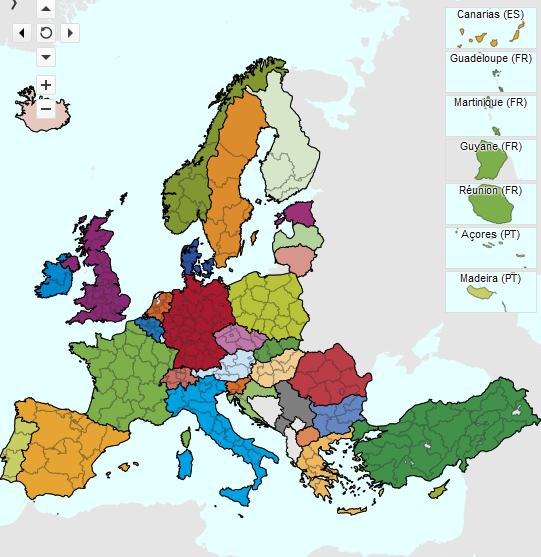

NUTS - The Classification of Territorial Units for Statistics

A special classification of territorial units for Statistics (NUTS; French: Nomenclature des unités territoriales statistiques) has been published by the European commission in 2015. Below there is an outline of the system of regionalization. The full publication can be downloaded via web http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/nuts/overview. The classification provides geocode standard for referencing the subdivisions of countries for statistical purposes. The standard is being developed and regulated by the European Union, so the system only concerns EU member states. The system is based on a hierarchy of three NUTS levels and it was published by Eurostat (2015).

The administrative divisions and subdivisions of some levels do not necessarily correspond to administrative divisions in the country. The first two letters on the code refer to the country. The subdivision of the country is then referred to with one number. Each numbering starts with 1, as 0 is used for the upper level. Where the subdivision has more than nine entities, capital letters are used to continue the numbering. The current NUTS classification, valid from 1 January 2015, lists 98 regions at NUTS 1 (see figure 01), 276 regions at NUTS 2 (see figure 02) and 1342 regions at NUTS 3 level.

There are three levels of NUTS defined, with two levels of local administrative units (LAUs). One of the most interesting cases is Luxembourg, which has only LAUs; the three NUTS divisions each correspond to the entire country itself.

NUTS regions are generally based on existing national administrative subdivisions. In the countries with only one or two regional subdivisions, or where the size of existing subdivisions is too small or too large, a second and/or third level is created. This may be on the first level (e.g. France, Italy, Greece, and Spain), on the second (e.g. Germany) and/or third level (e.g. Belgium). In smaller countries, where the entire country would be placed on the NUTS 2 or even NUTS 3 level (e.g. Luxembourg, Cyprus), the regions at levels 1, 2 and 3 are identical to each other (and also to the entire country), but are coded with the appropriate length codes at levels 1, 2 and 3.

From the NUTS regulation, an average population size of the regions in the respective level shall lie within the following thresholds. NUTS 1 between 3 and 7 million, NUTS 2 between 800,000 and 3 million, NUTS 3 between 150,000 and 800,000 inhabitants. The NUTS system prefers the already existing administrative units, with one or more of them being assigned to each of the NUTS levels.

Research Questions

The research is deals with two questions. The first is which European regions at level NUTS 1 and NUTS 2 are the most frequented destinations for Czech climbers. The other question is to determine the key climbing destinations for climbers of different states and regions.

Purpose of the Study

The aim of the research is to find out which European rock climbing destinations are the most visited areas by Czech climbers and what European regions at level NUTS 1 and NUTS 2 are the final destinations for this segment of sport tourism.

- The purpose of the study is to determine, which European regions at level NUTS 1 and NUTS 2 are the most frequent final destinations within sport tourism.

- European rock climbing destinations were compared in terms of number visits by Czech climbers.

Research Methods

The research is based on regionalization of rock climbing areas at level NUTS1 and NUTS2. Data sources were climbers’ logbooks on web portals. Data were processed by quantitative analysis of Czech climbers’ abroad trips to rock climbing destinations in Europe. The total of 2,535 abroad European climbing area visits made by the responding Czech climbers were monitored in the selected calendar year 2015.

In the analysis of climbing logbooks it was found out which foreign areas the Czech climbers visited and when they were in the given area. The evaluation was based on how many different climbing individual trips the climbers made abroad.

It was necessary to define the destinations for presentation and statistical processing of the research results. The regionalization of destinations primarily on the state level and then on the level of regions at NUTS 1 and NUTS 2 of the country was used. The selected regionalization is suitable for statistical processing and a subsequent comparison of the results in the segment of sports tourism.

Research Sample

The data for quantitative analysis were obtained from the Internet climbing logbooks where individual climbers record their ascents and performance. These data are freely accessible on the web portal www.lezec.cz. The climbers keep and continuously update the records of their performance as to the individual ascents. Their performance can be compared in a database of climbing logbooks.

A sample of 405 respondents was selected according to specific strict criteria. The basic sample to select from was a total of more than 4,000 climbers who had registered their climbing logbook, to which they continually recorded their ascents in the calendar year 2015. The data were collected in 2016, when the logbook records for 2015 had been completed. Data were processed in Microsoft Excel.

There were three key criteria for the respondents’ inclusion:

- Criterion of an active climber – the minimum of ascended routes in climbing logbook was 100 records.

- Criterion of complete records – the climbing records for 2015 were continuous throughout the year.

- Criterion of a foreign climb - climber had completed at least one abroad trip, with at least one successful ascent recorded in the logbook.

Findings

Criterion of a foreign climb was fulfilled in the respondents in the total of 21 foreign trips to European countries, included Turkey and Cyprus.

The most visited countries by Czech climbers in Europe were Germany and Italy (844 and 462 visited areas, see Table 01).

The medium visited countries in Europe by Czech climbers were Austria, France and Slovenia (136 – 222 visited areas, see Table 02).

As shown in Table 03, the least visited countries in Europe by Czech climbers were Norway, Turkey, Poland, Croatia and Greece (40 - 66 visited areas). Only few visits were count in Switzerland, Malta and Sweden (11 - 16 visited areas). The least visited countries were Belgium, Portugal, Great Britain, Cyprus, Luxembourgh and Romania (1 - 4 visited areas).

Findings at the level NUTS 1

The total of the NUTS 1 regions visited by the respondents in 2015 was 41.

The results of NUTS 1 regions are shown in Table 04. The most visited European region at NUTS 1 level is DE2 Bayern in Germany. Czech climbers (respondents) made 782 trips into this area. In this region there is the most famous and most visited sport climbing area in Germany, which is known among climbers as Frankenjura. Under this name the area is defined also in various climbing guides, for example by Schwertner (2012). It is followed by the regions ITH North-Est in Italy (335 trips), SK0 Slovakia (222), FR8 Méditerranée in France (151), ES5 Este in Spain (147) and SL0 Slovenia (136). The Italian region of North-East includes a vast area of sport and traditional climbing around the lake Lago di Garda. This area is commonly called by climbers “Arco Rock”, according to a cult climbing town. The name of “Arco Rock” is also used for this area as defined in the climbing guides. (Manica, Cicogna & Negretti, 2015).

Slovakia and Slovenia are smaller states, and thus the entire state is at the same time a region of NUTS 1. French Méditerranée region has a large number of legendary sport climbing areas. As an example the following areas can be mentioned: St. Leger du Ventoux, CEUS, Orpierre, Buoux or Gorges du Tarn. The region of Este in Spain is popular among Czech climbers mainly due to the areas of Margalef and Siruana.

In addition to the above mentioned most visited regions there are some other significant NUTS 1 regions worth mentioning in the individual countries. DED Sachsen (58 trips) in Germany, which is the cradle of traditional sandstone rock towers climbing. The region of ITG Isole (65) in Italy is represented by Sardinia and Sicily, two large Italian islands with lots of smaller attractive areas. Austria is represented by two regions of AT1 Ostösterreich (87) and Westösterreich (78). These are mostly smaller sport climbing areas. Concerning Norway the entire state is defined as NUTS 1 region of NO0 Norge (66).

Findings at the level NUTS 2

The number of the NUTS 2 regions visited by the respondents in 2015 was 66.

At NUTS 2 level (see Table 05), the most visited region is DE24 Oberfranken in Germany (605 trips into this area were made by the responded Czech climbers in 2015), ITH2 Provincia Autonoma Trento in Italy (315) and SK03 Central Slovakia (153).The biggest number of the sectors of the afore-said climbing area of Frankenjura is located in the region of Oberfranken. Other sectors of Frankenjura belong to German NUTS 2 regions of DE23 Oberpfalz (95 trips) and DE25 Mittelfranken (80). These regions were ranked on the 6th and 9th place within European NUTS 2. Here, it is one of the examples where the regionalization at NUTS 2 divides a sports touristic region or a region defined by the physical-geographical regionalization in several parts.

ITH2 Provincia Autonoma Trento in Italy includes the area around Lago di Garda, mentioned above as Arco Rock. In the area of SK03 Central Slovakia (153 trips) the most visited areas are Súlov and Porúbka. As to Slovenia, in the region of SLO2 Western Slovenia (134 trips) the important climbing areas to be mentioned are Mišja Peč and Osp on Istria. Both of them offer climbing routes of high difficulty. Another area situated there is Črni Kal, which is characterized by a number of shorter routes and of lower difficulty.

The French region of FR82 Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur (117 trips) is a traditional destination. In addition to the world-famous historic climbing areas such as Buoux, Céüse or Orpierre, the region can also offer newly emerging areas that attract top climbers from all over the world. Such an example is the climbing area of St. Leger du Ventoux, which offers climbing walls with big overhangs. The Spanish region of ES51 Catalunya (87), with the already mentioned sectors of Margalef and Siruana, has a similar nature. Austrian region of AT12 Niederösterreich (87) includes climbing areas of Adlitzgraben, Hohe Wand and Höllental, which are easy to access.

Concerning island regions, the biggest number of trips were on Sardinia (57), which offers lots of climbing areas. However, this can be misleading because most climbers manage to visit more climbing areas within one trip. Another island region is Greek EL42 South Aegean, where the island of Kalymnos is situated. This island is often called a climbing paradise and it is popular with climbers from all over the world. Spanish Balearic Islands ES53 (19 trips) are represented mainly by Mallorka. Other 14 visited climbing areas were found on the island of an independent state of MT00 Malta. Malta is also an example of the entire state being at the same time a NUTS 2 region. Among other frequently visited island regions there are Canarias ES70 (13 trips), namely Gran Canaria and Tenerife. A last of the big islands is ITG1 Sicilia (8 trips) and 2 visits were recorded on CY00 Cyprus.

Other significant NUTS 2 regions are within individual states listed as follows: SK02 Western Slovakia (68 trips), AT33 Tirol (62) in Austria, TR62 Antalya (56) in Turkey, ITC3 Liguria (46) in Italy, HR03 Jadranska Hrvatska (43) in Croatia, ES52 Comunidad Valencian (41) and ES61 Andalucía (37) in Spain. The most important region in Poland is Dolnoslaskie PL51 (38) and in Norway it is NO06 Trondelag (31). More than 30 trips were recorded in the French region of FR81 Languedoc-Roussilon (34).

When comparing the results of the survey in different regions it is necessary to evaluate them with regard to various factors that can affect the number of visits and thus the results. Among the factors there are especially the size and climbing potential of a particular mountain climbing area, the distance from home, seasonality and the related time spent in a particular destination. On one hand some of the mentioned areas have a great potential of climbing routes, such as the area of Arco Rock (ITH2 Trento), which is a popular destination for a week or weekend holidays and at the same time proper for spring and autumn season. Because of their distance, Spanish regions are typical for longer stays of climbers in one place, especially in winter months. The longest continuous visit, in duration of 40 days, was recorded in the climbing area of El Chorro in the region of ES61 Andalucia. On the other hand, foreign destinations close to the Czech Republic border are frequently visited for weekends, or even single days. Examples include Slovak regions, which are attractive especially for Czech climbers living close to Slovak border. A typical Czech climbers’ weekend destination is Frankenjura in the region of DE2 Bayern. In Frankenjura there was the record of the highest number of visits (19) made by one climber in one year. Climbers who travel to get to know a given region often visit a few smaller climbing areas during one trip, for example when travelling to islands of ITG2 Sardinia or MT00 Malta.

Conclusion

Regional hierarchy of NUTS1 and NUTS2 is suitable for statistical data processing for tourism business and economical purposes. The findings demonstrate a potential of different European regions for rock climbers as a special segment of sport tourism.

Answer to the question: Which European regions at level NUTS 1 and NUTS 2 are the most frequented destinations for Czech climbers?

The most visited areas for Czech climbers at the level NUTS 1 are Bayern in Gemany, Nord Est in Italy, Slovakia, Méditerranée in France, Este in Spain and Slovenia. The most visited areas for Czech climbers at the NUTS 2 level are Oberfranken in Germany, Trento in Italy, Central Slovakia in Slovakia, Western Slovenia in Slovenia and Provence-Alpes-Cote d'Azur in France

Answer to the question: What are the key climbing destinations in different states and regions?

The research results show the key European climbing destinations for Czech climbers, in terms of number of visits made in 2015. In Germany it is Oberfranken, Oberpfalz and Mittelfranken (climbing region of Frankenjura) and Sachsen (climbing region of Elbsandstein). In Italy it is Provincia Autonoma di Trento (Arco Rock climbing region), Sardegna and Liguria (climbing region of Finale Ligure). In Slovakia it is Central Slovakia (climbing area of Súlov and Porúbka). In Spain it is Cataluña (climbing area of Siruana and Margalef), Comunidad Valenciana (climbing area of Chulilla) and Andalucía (climbing area of El Chorro). In Austria it is Niederösterreich (climbing area of Adlitzgraben, Hohe Wand and Höllental) and Tirol (Zillertal climbing area). In France it is Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur (climbing area of St. Leger Du Ventoux) and Languedoc-Roussillon (climbing area of Gorges du Tarn). In Slovenia it is Western Slovenia (climbing area of Mišja Peč and Osp), in Norway it is Trondelag (climbing area of Hell and Flatanger), in Turkey it is Antalya (climbing area of Geyikbayiri), in Poland it is Dolnoslaskie (climbing area of Szczeliniec Wielki and Narozniak), in Croatia it is Jadranska Hrvatska (Paklenica climbing area) and in Greece it is South Aegean (Kalymnos Island).

Processing of the survey results outlined further research possibilities, both in sports tourism and geographical regionalization of climbing areas. The authors will continue in the analysis on a regional level in individual countries. The data collecting should be carried on and thus enlarged in a time span of several years. The results should provide a basis for comparison of European and also global trends in climbing sport tourism.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank to a Tourism Management student Radek Sedlacek for his help with the data collection and processing and also to a colleague Dagmar Hrusova for partial translation and English language revision.

References

Albayrak, T., & Caber, M. (2016). Destination attribute effects on rock climbing tourist satisfaction: An asymmetric impact-performance analysis. Tourism Geographies, 18(3), 280-296. DOI:

Atchinson-Jones, D. (2002). Europe: sport vertical. London: Jingo Wobbly Euro Guides.

Caber, M., & Albayrak, T. (2016). Push or pull? Identifying rock climbing tourists' motivations. Tourism Management, 55, 74-84. DOI:

Chaloupsky, D. (2014). Rock climbing in Czech paradise: Historical development of the frequency of traditional ascents at selected sandstone towers. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise, 9, S276-S283. DOI:

Cohen, S. A., Duncan, T., & Thulemark, M. (2013). Lifestyle mobilities: The crossroads of travel, leisure and migration. Mobilities, 10, 155-172.

Cresswell, T., & Merriman, P. (Eds.). (2011). Introduction: Geographies of mobilities - practices, spaces, subjects. Geographies of Mobilities: Practices, Spaces, Subjects (pp. 1-18). Burlington, VT: Ashgate

Eurostat. (2015). Your key to European statistics. [online] Retrieved March 20, 2017 from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/nuts/overview

Ewert, A., Gilbertson, K., Luo, Y., & Voight, A. (2013). Beyond "because it's there" motivations for pursuing adventure recreational activities. Journal of Leisure Research, 45(1), 91-111. DOI:

Goedeke, R. (1992). Der deutsche Kletter-Atlas: alle Felsgebiete Deutschlands von Helgoland und Rügen bis zum Karwendel und Watzmann. München: Berg.

Kulczycki, C. (2014). Place meanings and rock climbing in outdoor settings. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 7-8, 8-15. DOI: 10.1016/j.jort.2014.09.005

Manica, M., Negretti, D., & Cicogna, A. (2015). Arco rock. Milano: Versante sud.

Meadows, M. (2013). Reinventing the heights: The origins of rock climbing culture in Australia. Continuum, 27(3), 329-346. DOI:

Rickly, J. M. (2016). Lifestyle mobilities: A politics of lifestyle rock climbing. Mobilities, 11(2), 243-263. DOI: 10.1080/17450101.2014.977667

Rickly, J. M. (2017). “I’m a red river local”: Rock climbing mobilities and community hospitalities. Tourist Studies, 17(1), 54-74. DOI:

Rickly-Boyd, J. M. (2012). Lifestyle climbing: Toward existential authenticity. Journal of Sport and Tourism, 17(2), 85-104. DOI:

Rickly-Boyd, J. M. (2014) ‘“Dirtbags”: Mobility, Community and Rock Climbing as Performative of Identity. In T. Duncan, S. Cohen, & M. Thulemark (Eds.), Lifestyle Mobilities: Intersections of Travel, Leisure and Migration (pp. 51–64). Ashgate Publishers.

Schwertner, S. (2012). Frankenjura. Köngen: Panico-Alpinverl.

Thorpe, H. (2012). Transnational mobilities in snowboarding culture: Travel, tourism and lifestyle migration. Mobilities, 7(2), 317-345. DOI: 10.1080/17450101.2012.654999

Thorpe, H. (2014). Transnational Mobilities in Action Sports Cultures. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmilian

Toula, T. (2003). Rock 'n' road: an atlas of North American rock climbing areas. Guilford, Conn.: Falcon.

Weed, M. (2014). After 20 years, what are the Big Questions for sports tourism research? Journal of Sport & Tourism, 19(1), 1–4. DOI:

Zelenka, J., & Pásková, M. (2012). Výkladový slovník cestovního ruchu. Praha: Linde Praha.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

27 June 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-948-1

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

1

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-161

Subjects

Business, management, behavioural management, macroeconomics, behavioural science, behavioural sales, behavioural marketing

Cite this article as:

Chaloupska, P., & Chaloupsky*, D. (2017). Rock Climbing Tourism Destinations at Level Nuts 1-2 For Czech Climbers. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), Business & Economics - BE-ci 2017, vol 1. European Proceedings of Multidisciplinary Sciences (pp. 16-28). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epms.2017.06.3