Abstract

Today's Romanian migration towards the developed EU countries is one of the most complex and dynamic movements in Europe. In this context, we wonder what is the current state of the scientific literature regarding the rural perspective of this phenomenon? Also, what are the main directions, and socio-economic effects of the workforce emigration from rural Romania? Using a qualitative approach, with some quantitative elements, as well as documentary and content analysis, we performed a critical systematic literature review of the articles accessed from Google Scholar regarding the Romanian rural migration. The main themes identified in these articles are: the emigration destinations after the 2008 Economic Crisis; remittances; remigration; migration returns and entrepreneurship; socio-economic effects of emigration on the rural parts of Romania (on the family, health system). Our findings show that the main destinations for low skilled labor are Italy, Spain, Greece, Portugal, and post-crisis, the Northern Europe, while destinations such as France, Germany, UK have more complex migration patterns. Furthermore, we encountered remigration, brain drain (students, medical personnel), migration return and entrepreneurship, the separation of families and child abandonment or negligence, lack of workforce in agriculture or the related high costs, Roma emigration, as well as also gender differences. With over 3 million people, the post-communist Romanian emigration risks compromising the long-term chances of development in the original country. For the rural parts, the problems are even greater, since the youth are leaving for the cities. Likewise, the adverse socio-economic effects are harder to counter, due to the limitations in the rural areas (access and quality of education).

Keywords: Rural Romania, Romanian migration, socio-economic effects, literature review

Introduction

The transition from the planned economy to the market, as well as the post-communist socio-economic changes have left their mark on the evolution of the rural population, not only regarding structure and quality but also regarding numbers (Török, 2014).

Our research captures the changes in the countryside, where migration has exhausted localities of their most valuable resources, the people. With an area of over 200,000 km2 of the rural environment, Romania is among the main agrarian countries in Europe, and although it has good quality land, the real human capital is declining in this sector, which is causing significant agricultural performance problems.

The most important characteristic of the effects of migration is the social restructuring in the locality of origin, building a real culture of migration, especially in rural areas (Moraru & Munteanu, 2014).

Therefore, we are witnessing a dramatic phenomenon, Romania's rural areas becoming less attractive for the young people, who are often attracted by the mirage of the major cities. By analyzing the situation from an economic perspective, we understand that the rural labor force has adapted to the reality, and has identified other ways to meet its needs. The experience of the informal economy in the communist years and the spirit of adaptation of the Romanian migrants in rural areas has formed a human and social capital that was exploited abroad, in Italy, and even in France. However, not only the migration experience and the law limiting practices of the communist regime survived in the new economic context, supporting their achievement of these objectives, but also more traditional values and old practices (Larionescu, 2012).

The decline of the Romanian population, more pronounced in rural areas, is a problem that can be solved if the economic development of these regions is pursued. The most important problem of the Romanian countryside is the dismantling of the traditional peasant family through aging and migration. Until 1990, many peasants commuted to nearby industrial towns but continued farm work at home. The definitive rural exodus towards France, Italy, Spain has deprived the villages of an important segment of their population (the most active, able to work), leaving behind only elders and children bearing in their heart the burden of the desire to have parents close (Török, 2014).

However, changes in the rural labor force have negative effects at both local and national levels, generating a decrease in productivity. Migration does not only lead to the aging of the rural population but, primarily due to the migration of young people, also to the collapse of the agricultural economy by affecting the agricultural labor force. Although the labor force in agriculture is oversized compared to other sectors, it is not distributed proportionally in the territory and is especially characterized by the improper use of the factors of production, which determines the inability to secure a source of income. The deruralization is the one that brings to the forefront those peasants without a job, who are socially assisted by the state and who pass on this life strategy to future generations. This is happening quickly, since the land does not attract young people, despite government programs, and countering it requires saving rural areas with great potential but often not being used to the maximum (Moraru, & Munteanu, 2015).

On a closer inspection of the spatial patterns of migration distribution, Török (2014) has found that the negative rate of migration in a locality is influenced by the negative rate of migration in neighboring localities. This phenomenon is explained by the aging population and the low birth rate. The lack of companies and employment opportunities, as well as the low level of income in the agricultural sector, make these areas less attractive. This situation is even worse where there is a negative rate of migration accompanied by negative birth rates (Török, 2014).

On the other hand, the construction and decoration of a home are one of the main objectives of migrants, the house becoming a symbol of wealth and social ascension that mobilizes a significant part of their remittances. The new rural homes are moving away from the traditional pattern, both in the formal configuration and in the colors and materials used in the façade design. Old building materials (especially wood) are rejected because of their connection with traditional small houses, witnesses of a painful past, migrants prefer the use of quality materials (imported or brought from the host country). Many dwellings, some of them as yet unoccupied, as well as the generous dimensions of the newly constructed houses, led to the situation where two neighboring buildings can be located at a small distance from each other. In addition, migrant investment has contributed to the development of the construction sector locally and to rising construction land prices, building materials and labor. Therefore, migration favored the import of new construction systems, construction techniques and equipment, as well as more efficient, more effective heating and sanitation systems and water and electricity supplies (Jacob, 2015).

While migration changes the social mobility trajectories and builds the "rurban" villages, where the standard of living and lifestyle combine the new and old lifestyles, still these communities gradually start to resemble those of the destination countries and the urban localities in Romania, rather than the traditional rural space (Alexandru, 2012).

Problem Statement

The Romanian migration started after the 1989 revolution (Quffa, 2014), and is one of the biggest, most complex and dynamic migration movements directed towards the developed European countries, USA, or Canada.

Any valid assessment of the Romanian migration should include: an evaluation of the structural factors determining it; a structural analysis of factors that attract migrants to destination countries; a review of the motivations and expectations of individuals responding to these structural factors; a socio-economic research of the structures that are being developed to connect emigration with immigration areas.

While this is a complex model that offers a broader view of the phenomenon, it is easy to reduce to the pull/push model. By the same integrative approach, contemporary specialists, mainly sociologists, show that the dynamics of international migration (including: the emergence of new forms such as travel for work or that of the retired people; the feminization of migrant classes in some regions of the world; the phenomenon of brain drain and its complex consequences) call to readjust the theoretical perspectives by combining them with new research paths to be translated into models for all three levels of analysis (macro, mezzo and micro) (Sîrca, 2014).

Micro level

At the micro level of scrutiny, Romanians wanted to move/work in richer countries to improve their financial situation and to be able to offer a better future to their children, but also due to some psychological or social reasons (Cristian & Baragan, 2015).

The typology of migrants presents several sociological aspects. The definitive emigration is common for people with superior qualification (IT, science, sanitary system), well-qualified personnel with medium education, individuals with excellent network support, or those in search of a new life. Withal, temporary emigration is customary to low/medium-skilled young people, from middle class or under (the poorer or uneducated don’t migrate productively), individuals that manage to grab opportunities, niche craftsmen, the resilient with material resources (Sîrca, 2014).

Another interesting trend, especially in the rural areas, is the feminization of low-skilled migration (Quffa, 2014), mostly due to the labor market dynamics of Spain or Italy. Since, after the 2008 crisis, fewer workers were needed in construction (a field dominated by men), low-skilled women migration in support of their family increased, because their working fields (elderly or children care, for instance) were less affected by the crisis. Of course, the lack of opportunities for women plays a major role, particularly in rural Romania, for many the work abroad being their first job.

Mezzo level

The analysis at the mezzo level is reserved for the regional studies of migration in Romania. The historical regions of Moldova, Muntenia, and Oltenia, which fall into the North-East, South-East, South and South-West development areas, are those in which temporary migration is more intense (Vîlcea et al., 2013).

The South-West Oltenia region is a source of emigration (alongside with the North-East, South-East, South and South-West), while the regions receiving migrants are West, Center, and Bucharest-Ilfov regions. Furthermore, there is a correlation with international migration, considering that the regions which are losing their population are all mentioned as the sources of internal migration (Vîlcea et al., 2013).

The South-West Oltenia region follows the national migration trend, registering an increase of migration from the rural areas where subsistence agriculture is practiced (Vîlcea et al., 2013). Also, between 2012-2015, youth circular emigration slightly rose from 59% to 61% from the total number of temporary emigrants, so this group could consist of the higher-skilled workforce working or looking for a job abroad. At the same time, despite the increase in temporary migration from urban areas at the national level, in the South-West Oltenia region, for both female and male, the rural origin of the phenomenon prevails. In addition, regarding the urban youth temporary emigration, there are greater differences between the counties of the South-West Oltenia region. For instance, the Dolj County registers the biggest rate of temporary youth emigration in the South-West Oltenia region, a rate higher than the national average rate of temporary youth emigration. On the other hand, the Mehedinți County has the lowest rate of temporary youth emigration in the South-West Oltenia region (Babucea, 2016).

The general migration situation of the North-East region is similar with the one at the national level. On the short term, the migration for work of those without high qualification may release the pressure on the labor market, which is faced with unemployment and poor work conditions, or opportunities. On the other hand, the migration for work of the high-skilled workforce results in brain drain, and its effects are damaging the quality of the education and health system, but also the work productivity. Due to emigration and to the decrease in the birth rate, many settlements in the region are faced with population aging, which may result in an increasing pressure of the assisted population over the active one (Cristian & Baragan, 2015). For instance, Slănic Moldova’s population started to decrease since 2002, after an ongoing increase between 1992 and 2002, Cireșoaia having the highest emigration rate, also men emigrate the most between 30-34 years, while the women between 45-49 (Moraru & Muntele, 2014). One of the counties most affected by the emigration of the Nord-East region was Bacău, while Iași has a positive migration balance (Moraru, 2015). Furthermore, Bacău’s migration started earlier and the strategies adopted were more complex than in Vaslui, on the other hand, the latter evolved into a social epidemic present everywhere. Regarding the importance of religion in Botoșani county’s migration, 90% of the population are Christians, and the Neo-protestants and Catholics played a major role in establishing the migration networks, while the pioneers were of Pentecostal faith (Bunduc et al., 2014). In addition, in the North-East region, and particularly in the rural areas, the feminization of emigration for work is very noticeable, this affecting the birth rate and population numbers, and in the end becoming more severe than the male migration for the region (Moraru et al., 2015).

Macro level

On the macro level of analysis, regarding the economic factors facilitating the Romanian international migration, we stress the correlation between post-Decembrist deindustrialisation process, which created much unemployment, and the increase in domestic labor migration flows towards Western Europe (Iano, 2016).

Therefore, we highlight the connection between employment rate and its effects on the Romanian migration phenomenon (Şerb & Cicioc, 2014), especially on rural emigration, since there is a lack of job opportunities, due to the poor diversification of economic activities, an aspect Romania is trying to tackle through the National Rural Development Programme. Of course, the state of education in the rural areas plays a role in this matter as well, since too many people have average or low qualifications.

As we will see later, the phases of post-socialist Romanian external migration overlap to a large extent with the changes in the labor market. This is due to the low number of reforms, the inhibition of the private sector by corruption and bureaucracy. The effects were felt in the labor market, the main consequence being the mass emigration for work to Israel, Germany, Spain or Italy (Jurvale, 2013).

While, on the demographic level, in the Romanian post-socialist era the negative birth rate drove the natural growth towards a negative trend, despite the increase in life expectancy, in the long run affecting the young workforce (Moraru & Munteanu, 2014).

Therefore, deindustrialisation and the population decline also lead to the change of the traditional direction of the internal migration from rural to urban, in the reverse order, from urban to rural areas (Iano, 2016). It was a method of survival for the unemployed or retired who were unable or unwilling to emigrate (Moraru & Munteanu, 2014). Thus, they found a cheaper way of life in rural Romania, practicing subsistence agriculture, and receiving social aid from local authorities, consequently becoming dependent on the political factor.

While Romania’s accession to the EU played its role in boosting migration, the mass migration was not necessarily only caused by the development differences between the West and East, but also by how the ex-communist states were integrated into the transnational production and exchange circuits (Stan & Erne, 2014).

Sîrca’s (2014) research entitled, reveals another interesting point of view. The demographic aspects relate to the actual migration issues, politics, and policies, entrepreneurship, opportunities, institutional crisis and local/global identity, values, reproduction of underdevelopment through the emigration of the poorly qualified labor force and that of the specialists.

Thus, the youths left the countryside in high numbers. Some headed towards cities to complete their education, but others joined the labor migration flows towards Spain and Italy before the crisis, and nowadays, in a bigger proportion than before the crisis, towards the Northern Europe, for example, leaving to work in agriculture in Denmark. At the same time, some of the elders left the countryside to join their families abroad to provide care for the children. As such, there are places, especially in rural areas, where 50% of the population emigrated, resulting in the creation of tight groups of Romanian migrants in destination countries (Lupu, 2015).

On the external factors that influenced the Romanian international migration, we highlight the international political climate. For instance, at first, Romanians have chosen to emigrate to the countries where the migration policies were most permissive towards irregular migration, or where one could easily get a work permit (Matichescu et al., 2015).

Research Questions

Doing our inquiry, the following questions came up: In what direction did the migration research go between 2016-2012? What kind of studies did it approach? Is there a connection between the intensity of a migration subject and the impact of that issue? What are the main migration directions? What are the most important socio-economic effects of the mass international migration (on the family, brain drain, consumption, construction, the rural society)? What can be done to stop the mass emigration? Can Romania still develop if the workforce emigrates at this rate?

Purpose of the Study

Our goal is to reveal a comprehensive picture of the Romanian mass international migration, with an emphasis on rural areas. Furthermore, we intend to investigate which types of migration articles were written more often than others.

Research Methods

The main method used was documentary investigation, in conjunction with statistical observation and content analysis. The tool used to find the materials was Google’s Scholar (GS) search engine. The keywords were: Rural Romania migration. We managed to access the articles either by database search, or by asking the authors for a copy, therefore we thank all of those who helped us. Our final sample contained 64 articles. By their scope, we grouped the studies into General, Destinations, Regional, Family, Brain drain, Remittances, Rural, Ethnic categories (all being results of migration).

Findings

The most significant periods of the post-socialist Romanian migration were: 1990-1993, a period dominated by ethnic migration and asylum seeking. The main destination countries were Hungary and Germany (due to human rights violations in Romania); 1994-1996, a time in which a rather small number of Romanians migrated in search for better jobs, or education opportunities. The main destination countries: for labor, Germany, France, Spain, Italy, Greece, Israel; brain drain, the USA, and Canada; some ethnic Hungarians migrated towards Hungary or Western Europe; and asylum seekers, in Germany; 1997-2001, a notable increase in circular and irregular migration from Romania, human trafficking, official labor migration deals with Germany and Spain; 2002-2006, marked by the granting of the free movement right to Romanians in the EU and Schengen space, a new era of migration for work began, most desired destinations for the low-skilled workers being Italy and Spain, while brain drain was directed towards France, UK, Germany; 2007-2016, starting with Romania’s accession to the EU, this period was affected by the 2008 economic and financial crisis, and the austerity measures the Romanian authorities took to counter it (cost cuts in the public sector), but also by the more recent economic recovery. The favorite destinations of Romanian low-skilled workers were Spain, Italy, Greece, and Portugal.

There is a lack of data and studies on the Romanian non-definitive migration to Spain, and analyzing the life of those on the move (in the term of work mobility) could explain the macro perspective, including their return chances. Living the life on the move makes the notion of the border between home and abroad, traditional and nontraditional, or here and there confusing. However, these European citizens also live between symbolic and mental boundaries. Hence the need to create a theoretical framework for the research of the international work mobility of Romanians (Marcu, 2012).

The Romanian migration to Central European countries was characterized by ethnicity and seasonality, and usually, the migrants remigrated later to Western European countries.

A more complex workforce migration (ethnic, students, physicians, engineers, IT specialists) took place towards Germany, France, UK, and Belgium.

After the 2008 crisis, Romanian migrants, some of them who remigrated from Spain, took an interest in the Northern European countries, determining both labor migration, and brain drain.

While it could be argued that the young Romanian emigrants give the direction of the phenomenon (Șteliac, 2014), it is hard to clarify the full extent of Romanian migration, for both authorities, and the specialist. Even so, per Eurostat, post-socialist Romanian migration numbers over 3 million people.

Ethnic migration

On the topic of ethnic migration, one of the most important research areas for the Romanian migration studies is the Roma mobility in the EU.

For instance, Pantea (2012) assesses that the migration of Roma women is largely dependent on the gender regime of the home community. Even if migration does not mean abandoning their maternal role, migrants must make a considerable effort to ensure a sense of respect in the community. While men's migration is usually seen positively (the husband as the family supporter), the migration of Roma women is poorly accepted socially. The idea that Roma women could migrate alone is not accepted by social norms, and violation of standards brings moral sanctions. Pantea’s findings support the hypothesis that Roma women perceive migration both as emancipation and as an experience that brings social costs, a phenomenon that is probably less common for women in most of the population. They have to walk on a blurred line between community-specific obligations to share and a more individualistic need to reach their potential or to earn their existence. Overall, the migration of Roma women is for and about the survival of the family and the achievement of decent living. This result is in contradiction with the literature on women's migration, with consumerist motivations. Also, Roma women seem to experience the separation of children as a higher cost than migrants from the majority population. They leave with a feeling of insecurity about leaving children caregivers and seem to allocate a higher percentage of income to maintain family ties. Because of serious financial problems, migration is a form of taking care of children for them.

In addition, there is a struggle for access to the privileged network, many of the most vulnerable being excluded. At the same time, the migration of those from poor communities, located away from the strong migration networks, pay the highest price of exclusion, being exposed to human trafficking. On the other hand, the social relationships are not static: they change over time, and migration is a process that can drive and accelerate such dynamics.

However, their migration seems to increase the economic and social benefits for Roma women who already have some power and social capital. For them and their families, migration becomes a way of life, not necessarily caused by poverty.

Conversely, migration brings minimum benefits and high social costs to those who are vulnerable and disadvantaged from the start. For them, migration is far from being an outflow of poverty; on the contrary, there seems to be evidence that in these cases migration is generating poverty. In the worst cases, they become stigmatized at home and migration becomes a cycle that perpetuates both economic and social causes (Pantea, 2012).

The author’s research confirms the results of other studies suggesting that the success of migration is based not only on the existence of a network but also on the existence of a currency of exchange, the migrants acting as "gatekeepers" behave like agents, providing credit in accordance with their needs and other economic actors who gain more power by mediating migration. Furthermore, the human trafficking is much more heterogeneous than it is usually considered, the boundary between exploitation and aid is vague, fluid and contextual. Also, people's response to trafficking and exploitation is diverse, with social costs for those who claim to be victims, and the complicated dynamics of Roma communities make it difficult to learn from these negative experiences (Pantea, 2013).

Another interesting perspective on the matter is that of Troc’s (2012) in a study entitled, in which he challenges the idea that Roma groups, due to their alleged traditionalism, always fail in their attempt to integrate into society and to follow, like other ethnic groups, the steps towards modernization and a healthy community development. While the Roma might have their responses to the circumstances of modernization, they are not determined, in the first place, by a cultural specificity that is preserved, despite all the chances (on the contrary, the central values and models of social action of the groups are affected in depth in the process), but rather by the particular social history of the group, the preservation of its archaic social relations, but also because of their discrimination in Europe (Troc, 2012).

With respect to the migration of ethnic Croats from Romania, Anghel (2012) in a study entitled, underlines the role of ethnicity in migration. Romanian Croats emigrated to Serbia, then to Croatia and later to Austria. In these phases of migration, 3 uses of ethnicity were revealed: ethnicity as linguistic access, facilitating employment and widening social capital; ethnicity as a way of acquiring legal status, giving access to citizenship, rights and opportunities; ethnicity as a form of transnational solidarity with co-ethnic minorities, providing access to additional forms of social trust allowed by minority organizations. In this context, migration networks act as a provider of opportunities in a context where ethnicity was the structuring factor of this migration. In the present research, two social resources (social capital and migrant ethnicity) allowed the easiest and most successful migration, as well as economic prosperity for migrant households (Anghel, 2012).

Remittances

One of the most significant benefits of emigration for Romania are the financial remittances.

There is an extensive literature on remittances, Lucas & Stark's paper being the most famous and cited work. The authors have divided people's motivations to send financial remittances to their family (for support), personal reasons (because they want to come back and use the money for themselves), for safety, investment, and social pressure (Pașca & Pop, 2016).

At the micro level of analysis, the beneficiaries of remittances are the remitters or their close relatives. While, at the macro level, the benefits are reflected in increased household consumption, declining poverty, recovery after macroeconomic shocks and social imbalances, the balance of payments support (Pașca & Pop, 2016).

For example, on estimates based on multifactorial regression models analysis in a study entitled, Goschim (2013) found that the impact of remittances on economic growth in Romania, between 1994-2011, was significant and positive which should prompt leaders to promote more public policies to exploit the remittance investment potential as one of the engines of economic growth in Romania (Goschin, 2013).

The higher or lower remittance behavior of the emigrants is influenced by factors such as gender, age, educational level, civil status, social class, the length of stay or opportunities in the country of destination, salary level (Pașca & Pop, 2016).

There are about 3 million Romanians working abroad, and their remittances are an economic advantage for Romania, stimulating consumption, investment and improving the wellbeing of society. In this respect, Romanians have sent so far around 54 billion euros into the country, most money in 2008 (7.8 billion euros) (Pașca & Pop, 2016).

Concerning the negative effects of remittances, we note the rising inflation, inactivity or unemployment of those who receive remittances (they prefer not to look for a job) (Pașca &Pop, 2016). Also, according to Iano (2016) the remittances in rural areas promote laziness, which in turn negatively affects the organization and operation of agriculture. In addition, the resulting lack of skilled human resources in Romania, due to emigration, leads to a decline in competitiveness in comparison with the EU (Boghean & State, 2014). Furthermore, due to the 2008 crisis, the financial remittances almost halved (Pașca & Pop, 2016; Iano, 2016). Based on the statistical analysis obtained by Boghean and State (2014), in their study entitled, it can be concluded that there is a definite negative correlation between the employment rate and the volume of remittances in Romania, in other words, the low employment rate leads to an increased migration rate, triggering a high level of remittances into the country. At the same time, the high level of remittances also has some negative effects on the labor market, with the population refusing to employ insufficiently paid jobs (Boghean & State, 2014). Even more, by OECD remittances in the rural areas are not often directed in an important proportion of investments (Basarab, 2015).

Entrepreneurship of returned migrants

Another advantage worth mentioning refers to the benefits derived from the entrepreneurship spirit of the return migrants, even if they are in small numbers so far. At the same time, since it is in the interest of the Romanian authorities to persuade people to return home the efforts in this direction must be more consistent. Some initiatives for remigrants, such as those of a financial nature (tax breaks or educational support for children) designed to facilitate their reintegration in Romania, could ease their return (Rentea, 2015). In addition, the state could offer guarantees to facilitate crediting for the migrants who want to invest in rural areas of Romania, even if they are not returning (Pauna & Heins, 2012). At the same time, improving the quality of consular services from the most popular migration destination is also needed (Pauna & Heins, 2012). Furthermore, offering grants for publications, associations, or radio stations abroad would be beneficial (Pauna & Heins, 2012). Regarding the return, the interested parties could facilitate the reintegration process, tackling employment and social issues, or the psychological, educational or cultural adaptation. However, the success of these measures depends on how well the migrants are doing in their destination country, and on the quality or the amount of social and economic remittances they would return with (Rentea, 2015).

Migration also has social and psychological implications, at the micro (individual) or macro (societal) level, and the social change is the defining phenomenon. The factors that highlight the social changes are: material (money earned, possibilities and opportunities they had); psychosocial (the impact of the new social environment on the migrants, through adaptation and integration); humanities (the social relations in the host society); professional (new jobs or labor performed); cultural (language learning, adopting habits and cultural elements).

Once the changes occur, they are expected to produce positive or negative effects on the entire inner or extra-migratory system (in the family, origin community, host community) (Cormoş, 2014).

Some returning migrants, especially in rural areas, may become agents of change in their communities of origin. Therefore, returning migrants can be a resource for rural development through investment, bringing varieties and new breeds of animals (Cîmpean, 2014), or through their pro-social behavior in the community.

Brain drain

As to the adverse outcomes of mass international migration, the brain drain effect is one of the most damaging, and one of the most dangerous forms for Romania is the physicians’ emigration.

The emigration of health professionals is a severe problem in Romania. The cause being a deep demotivation of the medical personnel, because of the poor working conditions, the lack of appropriate incentives for the quality and quantity of work provided, the absence of future job advancement (which is not always based on competence), the wish for a better life abroad (Frâncu, 2015; Feraru, 2013). The outcome being the emergence of an imbalance of health professionals at the national level, especially in the poor areas (rural Romania), and the appearance of inequities, regarding the addressability and access to health (Frâncu, 2015). After 2007, according to the Romanian College of Physicians, 10.000 doctors have chosen to go to work in the West, and at least 400 new requests are registered monthly at the Romanian Ministry of Health (Feraru, 2013). From an economic perspective, the migration of doctors from Romania abroad is a loss of the amounts invested in the training and specialization of physicians. Now, the state pays approximately 8.000 lei per year for each medical student and about 21.000 for each year of residency. These expenses last between 6 and 11 years for each future physician, so Romania spends about 70.000 lei for each student. If over 20.000 doctors have left Romania so far, it means that Romania has lost over 400 million euros (Feraru, 2013). This situation calls for better public health policies to harmonize population health needs, by offering enough professionals, but also by creating a coherent system capable of keeping doctors and nurses in Romania, by adopting measures to motivate them to stay, especially the younger ones (Frâncu, 2013). For example, the state could make strategies to support doctors moving to rural areas, or stimulating the association of several specialists in a medical practice, with assistance from the state. On the other hand, it is important to realize that there are no perfect medical systems, in most EU countries there is a lack of doctors in the rural areas (Feraru, 2013).

Regarding the migration of the skilled labor to Spain and the adverse brain drain effects it causes in the origin country, it is important to elucidate the temporary or definitive character of this phenomenon. The literature underlines the connection between the different levels of analysis (macro, mezzo, and micro) in the formation of certain emigrant typologies, but also highlights why some migrants are more prone to settle in Spain than others, or what type of migration strategy they choose to use. The first category is composed of people who are greatly affected by structural problems in the origin country, at economic and political level. They organized on the social media to access the qualified labor market. The second type seems to be less affected by economic and political factors than the first. Their motivation is to make an international career, but they face structural obstacles, of legal or economic nature (such as the economic crisis, in Spain). Thus, they take advantage of study opportunities to access later better jobs. The last case is reserved for those who are recruited by multinational companies. Mainly, this migration has less to do with the structural push factors in the origin society, or with the pull factors from Spain, and more to do with the incorporation into the qualified Spanish labor market thanks to globalization, and it offers immigrants a smoother transition in the destination society (Petroff, 2016).

Another important form of brain drain for Romania is represented by the students who attend school abroad, but do not come back. Between 2008-2013, the most important factors influencing their decisions to study in abroad (Austria, Bulgaria, Denmark, Finland, France, Hungary, Italy, Norway, Poland, Spain, Sweden, UK) are: the total numbers of international students in the destination country; the GDP/capita in the host country; the employment rate in the harboring state (Pașca & Pop, 2016). On the other hand, there are other socio-political and cultural factors that play a major role in making their decision (support network, the language in which they study, political climate, the cost of the studies).

In the same framework, to see what the future holds for student brain drain, we need to analyze the attitude of the Romanian youth (high school students), regarding the international migration and its effects in the globalizing era. In this regard, 87% of the young Romanians studied by Nedelcu (2015) in the article entitled, know what migration means. In addition, they have a realistic perspective of globalization, most important characteristics of the phenomenon being: for 53%, the human rights (mechanisms and institutions); tolerance and intolerance, for 44%; peace versus war, with 33%; for 31%, the global warming and environmental protection; the globalization of commerce, with 29%; for 24%, the development of an international community and of a global conscience. Furthermore, they consider that Spain, USA, Italy, France, Germany, UK, Canada have the most numbers of immigrants, probably thinking of the places they know their family or friends went for work. On the other hand, the responders think Romania, China, Bulgaria, and Moldova have the highest numbers of emigrants, which is a rather accurate impression of the reality – since Romania exports the most students in EU (18% of the total, European average being only 5%) – while also having the lowest number of university graduates (from which 20% prefer to work in another country). Referring to the effects of international migration on Romania’s society, the high school students in question see them as being negative, from economic (80%, poverty; 78%, lack of job), political (80%, wars; lack of freedom, for 38%; the corruption of politicians, with 34%) and social perspective (on structure of the family, and on children left home). At the same time, 62% consider that emigration has positive economic effects on the destination society, not affecting too much the social, cultural, or political spectrum. Only 28% know anything about the immigration in Romania, but think a considerable increase of it would lead to a rise in criminality and discrimination in the society. 51% consider that immigrants are discriminated in the EU – discrimination being on ethnic or race grounds, most discriminated being the Roma (87%), African (61%), Romanian (57%) immigrants. Moreover, 60% believe that the host countries should give immigrants citizenship (Nedelcu, 2015).

Furthermore, based on the primary analysis of the Center for Urban and Regional Sociology (CURS) in Romania, it can be argued that the Romanian youth, being disappointed by the young political leaders and since emigration is a real alternative at this moment, choose to leave the country – whether it be a temporary or even a definitive stay, to meet aspirations, lifestyle or recreational activities. Also, we notice that the most mobile segment of the population is represented by young people, especially those under 19, being followed by those between 19 and 34 years of age. However, freedom of movement has not led to migration, it has only facilitated it. The Economic, social and political factors have shaped the migration patterns (Stoica, 2015).

Family

The Romanian post-socialist international migration also determines changes in the structure and life of the household, whether temporary or permanent migration is considered (Popa, 2016). In this respect, the migration affects the financial situation of the family and the relations between the family members (between the couple and with their parents and children) (Nemenyi, 2012).

In the, Luca, et al. (2012) are trying to identify the integration difficulties of Romanian children who emigrated to Italy and Spain, and the reintegration experience of children returned home after a failed migration project. Their findings show that between 2008-2012, 21.325 children returned from Italy and Spain requested to be reenrolled into the Romanian educational system. From those investigated at home, 92% want to live abroad, in 50% of the cases to live with their parents, and to a lesser degree for material reasons. Also, in 30% of the cases, at least one parent was already abroad, and only in 20% of the cases, the person taking care of the children in Romania was one of the parents. In half of the cases when migration occurred, the children changed multiple destination countries, but also their environment (37%, either from rural to urban, or from urban to rural), while 9% changed various settlements. About half of the remigrant children would opt for another migration, more boys than girls, and more often in urban, than in rural areas. On the causes of return, in 50% of the situations, both parents came back, with or without the approval of the pupil, after not adjusting to the school system, society, or culture in the destination country, or because they encountered financial problems abroad. The duration of the migration project has a negative effect on the emotional state of the remigrant children if it is longer than three years because it is harder for children to readjust to the Romanian society. While 10% of the remigrant children admit to having problems readjusting to the origin society, most of them have a positive state of mind about it, and only 17% regard it negatively. Between 10-15% of the remigrant children present a significant risk of developing a personality disorder, a total of 6.000 kids are facing difficulties readapting, or of emotional or psychological nature which may affect their future development. In the medium or long term, the number of children with severe emotional and psychological problems due to unassisted remigration will increase with about 1.000 every year (Luca et al., 2012).

In this context, in the study, the effects of parental migration on the children remaining in the country of origin, and on those who went abroad together with their families are analyzed, by comparing the attitudes towards parenting of two such groups of adolescents. The results do not show a notable difference between the attitudes towards parenting of the groups of teens who stay home, versus those who accompanied their parents aboard. However, the study findings suggest that parental migration correlated with leaving children at home may have a negative effect on the parent-child relationship, which may lead to more negative perceptions of parental behavior, in comparison with that of those of the reunited families. On the other hand, the teens left home from urban areas have a less positive attitude towards parenting, than those from rural areas (Popa, 2016).

Popa’s findings are partially supported by Cojocaru, et al. (2015) in the study The Effects of Parent Migration on the Children Left at Home: The Use of Ad-Hoc Research for Raising Moral Panic in Romania and the Republic of Moldova, who also adopt a cautious attitude towards the issue, rather than a rhetoric based on the deficiency paradigm, like some of the studies conducted by NGOs (probably to justify their programs). Often, such NGOs maintain and build the “moral panic”, and the same rhetoric about the parents carries a moral approach. Furthermore, even when part of the data collected by the researchers does not confirm the catastrophic discourse, public opinion is influenced, and the lack of data is not an impediment to setting up public policies under the pressure of the media or non-governmental organizations (Cojocaru et al., 2015).

On the other hand, migration leaves behind vulnerable and neglected children, lacking emotional and psychological protection, who require special attention from the authorities, especially when the parents, under the effect of poverty and unfulfilled needs, do not realize the adverse consequences on the neglected children. Also, given the possible effects of parental migration on children's education, it is important to help the children left at home and their parents who have gone to work by developing tools designed to aid parenting from a distance, and parent communication from abroad with the school. (Sănduleasa & Matei, 2015). The relationship between school and social assistance should be strengthened, by improving communication and procedures between teachers, principals, psychologists and social workers. Also, the role of the school counselor should be increased in rural areas (Păduraru, 2014).

From a historical point of view, women have been associated with immobility and passivity in their family migration project. However, as women became more prominent, and gained even more power in decision-making and planning, they often preferred to settle in destination countries thus challenging and provoking changes in the household's normalcy through gender-specific activities. Frequently quasi-emancipatory migration experiences have changed family dynamics, sometimes even at the level of structural factors. To clarify the dynamics of family life in the transnational context, researchers use the house management tools to highlight the migrants’ efforts to maintain a consistent and convenient migration project for all family members. In addition, based on the transnational view of migration, Badea, (2014) investigates the gender and age dynamics of the family members, in a study entitled, and shows that besides women, children and important family members are now involved in family decisions, representing more in the family than simply individuals who do work in the household .

In addition, in transnational families, in about 50% of cases parents receive monetary and non-monetary support from their grown children who emigrated (women more often than men). The amount of support depends on the possibility of the children working abroad and on the needs of the parents at home (Zimmer et al., 2014).

On the link between gender and migration, Vlase (2012) in, highlight the impact on the migrant society of origin and present their the research findings from a village in East Romania and Rome (the main destination of the population studied). The author emphasizes the migrants’ gender differences and their contribution to the socio-economic development of the society. Based on qualitative research, in the form of a semi-structured interview with migrants, and on participatory observation, their conclusions reveal different meanings of migration, (transfer of ideas, money or goods and local small business start-ups), by gender. From the perspective of the women who were part of the sample, development is related to the evolution of their personal situation (a high level of aspirations, widening the cultural horizon, new ways of expressing identity), while for men, development is related to local economic practices, which are often considered as an obstacle to development. Furthermore, the regularity of women's remittances (or types of remittances: clothes, furniture, and appliances) depends on the number of children left home to be taken care of by grandparents or other relatives. Hence the mothers’ sense of duty towards grandparents. The way in which migration affects the organization of the household in the country of origin is also an indicator of gender and intergenerational transformation, thus further evidence that development cannot be assessed solely by the study of economic indicators. Another notable result of the research is that it elucidates the reason for the invisibility of the financial remittances of women in Italy. Here, we can see that the differences in the gender delivery behavior are also caused by the rules of the home society. Because men are considered the main financial supporters of the family in the home community, they feel compelled to obey these rules, so they send more money and more often. However, this delivery behavior would not be possible without the financial contribution of women in Italy, so their contribution is less recognized in the home society (Vlase, 2012).

Migration-development paradigm

Regarding the migration-development paradigm, opinions are divided among specialists. One idea would be to have the state play a part in the administration of the resources provided by emigration, to foster future evolutions. A practical example is to implement measures to boost the information flux about existing economic opportunities, at the local or national level, to attract investments from the Romanian emigrants. A more difficult task would be to create a coherent strategy to include emigration as a resource for future development (Careja, 2013).

From a historical perspective of the migration-development paradigm in Europe, we can evaluate the possibility of Romania to follow the development route of Italy or Spain, and to become a country importing human resources, rather than a country exporting labor force (Încalţărău, 2012). In fact, Romania could be walking this road as we speak, after it had overcome the adverse effects of the 2008 economic crisis, incomes are increasing again, which could lead to future immigration. One example are the students from non-EU countries who can become doctors in Romania, being attracted by the recent increase in revenues in this sector (comparable to the EU average) and the easier integration into Romanian society, facilitated by the relatively small number of foreigners compared to the developed countries of the EU, and of course, to the vast lack of doctors (due to emigration). This is an example of how only structural reforms (income increases in the health system, improved work conditions, curbing corruption) in the origin country may stop emigration, bring development and with it immigration.

As such, we can say that there is a bizarre relationship between migration and development. The well-managed migration can be used as a tool for development, and development, in turn, can influence the dynamics and structure of migration. However, the cost-benefits analysis of Romanian international migration, from an economic perspective, reveals that the short-term advantages will not compensate the long-term losses. Thus, some forms of emigration could be encouraged, while others should not be at all (especially brain drain) (Stoica, 2012).

Conclusion

The territorial development of Romania, the new economic space structure, and the population are largely determined – in addition to processes that are dependent on directions – on new policies and social and economic circumstances (Török, 2014). Sîrca’s research suggests that the adverse effects of mass migration must be approached at the macro, mezzo and micro level (Sîrca, 2014).

: better absorption policies for the labor market; policies capable of stimulating the benefits received by employees; policies designed to create improved work chances for people (to counter the brain drain effect); policies based on the evaluation of push/pull factors of migration; the state institutions have to communicate and work better among themselves, through exchange protocols and coordination of elements concerning demography, population movement, and economic practice.

: public policies and communication orientated towards obvious problems of the middle, or micro level; collaboration with NGOs and other associations; supporting the local economy through development policies; specific policies which require community implication; policies suggested by specialists from associations meant to help individuals or groups punctually.

: by issuing social policies aimed at specific dysfunctionalities emigration facilitated (kids left home in the care of a single parent, or living with relatives; the Roma problem); strategies to enhance the collaboration between specialists and institutions to solve problems, or cases.

The Romanian authorities have been confronted, since 2008, with the internal and external socio-economic realities: the decrease in remittances; the Romanians leaving have no pre-established return plan; their children learn in foreign schools and integrate there; even if emigration helps the individual households, it does not sustain the community too much, and even less so at a regional level; migratory flows involve more and more diverse population categories, young people and families with children are the most numerous; the state has to deal with both brain waste (the inflation of diplomas in the country, uncoordinated with the needs of the labor market), and with the loss of the brains through emigration; the investment in human capital and education in Romania becomes a national cost difficult to recover on the long-term, rather than an engine for future development.

Therefore, international migration, even when is well managed, cannot replace an effective national strategy of human development. Emigration has small chances to offer development perspectives to a whole nation, at best it can accompany other efforts, at the local or national level, to reduce poverty and improve human development (Stoicovici, 2012).

The future structural evolution of the Romanian society will mostly depend on the human capital of the country that we will be able to create and keep in the national economy. While emigration drains the human capital and makes the stock unreliable, the financial capital has the potential to reduce its volatility. As such, investments in human capital could prove to be more stable and more profitable in time, and better at attracting external direct investments. At the same time, human capital is like a magnet for foreign companies, who can decide, especially in the Brexit context, to delocalize some activities towards a better business environment (Stoica, 2012).

To reinforce the investments in human capital, Romania should configure a national policy for employment depending on the real needs of the labor market. However, also, a strategy to harmonize the superior studies in Romania with labor market demand is necessary (Jurvale, 2013).

Regarding the rural areas of Romania, there are only two solutions left: we ignore the problems generated by the de-laboring of the workforce; we accept reality and seek solutions, if not for the elderly, at least for the youngest, who, for various reasons, leave the rural areas to obtain faster and safer financial gains, in their view, as against the practice of agriculture (Moraru & Munteanu, 2015). Perhaps the only rescue of the Romanian village remains the construction and the implementation of a large-scale national project aimed at the rebirth and development of rural space at all its economic, cultural, spiritual, political and social levels (Basarab, 2015).

In these cases, where the negative spill-over effects of migratory outflow, it is imperative to identify the strong points and opportunities that could bring development in the future, such as improving the regional infrastructure, the identification of tourist objectives and develop a very attractive business environment, to bring in foreign direct investment. Therefore, promoting rural development based on existing resources could be one of the most significant opportunities, as has been seen in some cases (Török, 2014). Moreover, the diversification of rural economic activities, together with specific needs of the countryside, could solve one of the biggest problems now, the aging of the population and the massive migration of young people to urban or overseas, indifferent of their professional qualifications. Improving conditions in education in rural areas would allow children to remain in the locality, not having to leave their homes to gain a satisfactory educational status (Preda, 2015).

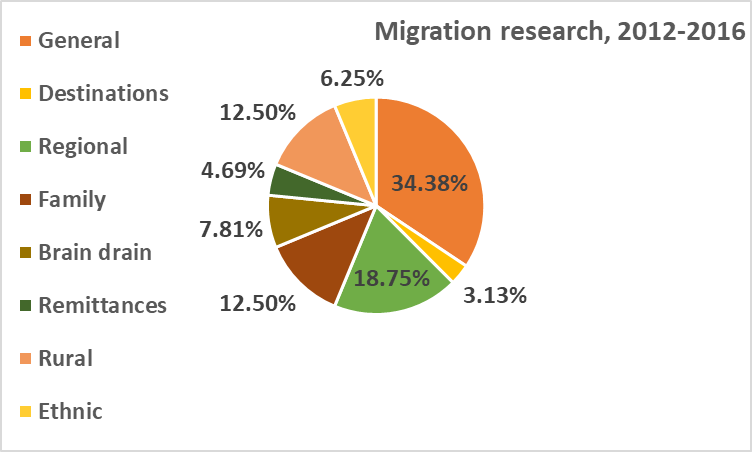

Regarding the quantitative review of the studied literature, we found that the most materials approached the migration subject from a general perspective, addressing the directions, socio-economic effects or development (34%). Another important part of the articles (18.75%) covered migration at the regional level, the North-East being the most researched geographical area. The rural migration and migration effects on the family were also approached by a significant number of authors (12.5% each). The analyses of the brain drain or remittances were somewhat rarer, but certainly not to be ignored (7.81% and 4.69%, respectively). The rest covered migration destination (3.13%), and ethnic migration (6.25%).

References

Alexandru, M. (2012). Stories of upward social mobility and migration in one Romanian commune. On the emergence of “rurban” spaces in migrant sending communities. Eastern Journal Of European Studies, 3(2), 141-160.

Anghel, R. G., Botezat, A., Coșciug, A., Manafi, I., & Roman, M. (2017). International migration, return migration, and their effects. a comprehensive review on the Romanian case. IZA Discussion Paper No. 10445. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2895293

Anghel, R. G. (2012). The migration of Romanian Croats: between ethnic and labour migration. Studia Ubb Sociologia, 57(2), 9-26.

Babucea, A. G. (2016). Analysis of the temporary emigration at the level of South–West Oltenia region of Romania - study of case: the young adult. Constantin Brancusi University of Targu Jiu Annals - Economy Series, 1, 13-18.

Badea, C. (2014). Dynamics and Decision‐Making Processes in Transnational Families: Home‐Making and Return of Romanian Labor Migrants. (Master Thesis). CEUeTD Collection. Retrieved from http://www.etd.ceu.edu/2014/badea_camelia.pdf

Basarab, E. (2015). Social Impact of migration upon the Romanian rural regions. Annals of the Constantin Brancusi University of Targu Jiu-Letters & Social Sciences Series, 1, 135-140. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/OsPfJh

Boghean, C., & State, M. (2014). The impact of remittance flows on the labour market of Romania and the EU countries. Annales Universitatis Apulensis Series Oeconomica, 2(16), 1-3.

Bunduc, P., Sochircă, V., & Bunduc, T. (2014). Rolul structurilor confesionale ale populaţiei în conturarea migraţiei internaţionale din judeţul Botoşani, România, Studia Universitatis Moldaviae, 6(76), 113-118.

Careja, R. (2013). Emigration for Development? An Exploration of the State’s Role in the Development Migration Nexus: The Case of Romania. International Migration, 51, 76-90.

Chirvas, C. (2015). Teorii clasice şi moderne ale migraţiei internaţionale, Conferință științifică internațională „Abordări clasice şi inovatoare în gândirea economică contemporană”, Ed. I (8 mai 2015) / com. șt.: Dumitru Moldovan [et al.]; coord., resp. de ed.: Elina Benea-Popuşoi. – Chișinău : ASEM, 2015. – 204 p. Antetit.: Acad. de Studii Econ. a Moldovei, Catedra Gândire Economică, Demografie, Geoeconomie. – Texte: lb. rom., engl., rusă. – Bibliogr. la sfârşitul art. – 40 ex. Retrieved from http://irek.ase.md/xmlui/handle/123456789/134

Cîmpean, S. (2014). Migration Phenomenon between the Departure, Return and Change of Lifestyle. Revista de Asistenţă Socială, 13(3), 125‑136. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/TMdZr7

Cojocaru, Ș., Rezaul Islam, M. & Timofte, D. (2015). The Effects of Parent Migration on the Children Left at Home: The Use of Ad-Hoc Research for Raising Moral Panic in Romania and the Republic of Moldova, Anthropologist, 22(2), 568-575.

Cormoş, C. V. (2014). Mentality and Change in the Context of International Migration. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 149, 242–247.

Cristian, E. R., & Baragan, G. L. (2015). Identification of main economic and social causes of Romanian migration, Ecoforum Journal, 4(2), 164-169.

Feraru, P. D. (2013). Romania and the Crisis in the Health System. Migration of Doctors, Global Journal of Medical Research, Interdisciplinary, 13(5).

Frâncu, V. (2015). Health professionals, migration, deficiency, quality of healthcare, health status. AMT, 20(1), 9-11.

Goschin, Z. (2013). The remittances as a potential economic growth resource for Romania. Annales Universitatis Apulensis Series Oeconomica, 15(2), 655-661,

Iano, I. (2016). Causal Relationships Between Economic Dynamics and Migration: Romania as Case Study. In J. Domínguez-Mujica (ed.) Global Change and Human Mobility. Advances in Geographical and Environmental Sciences (pp. 303-322). DOI:

Încalţărău, C. (2012). Toward Migration Transition In Romania. CES Working Papers, 726-735.

Jacob, A. (2015). Efecte ale migraţiei internaţionale asupra locuirii în ruralul românesc. Cazul comunei marginea, judeţul suceava, România, Calitatea Vieţii, 26(3), 238–263.

Jurvale, D. (2013). The consequences of external migration on romanian labor market, MPRA Paper No. 44989, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/12035787.pdf

Larionescu, A. L. J. (2012). Migrants’ housing in the homeland. A case study of the impact of migration on a rural community: the village of Marginea, Romania. Journal of Comparative Research in Anthropology and Sociology, 3(2). Available from https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1P3-2945476901/migrants-housing-in-the-homeland-a-case-study-of

Luca, C., Foca, L., Gulei, A. S., & Brebuleț, S. D. (2012). The study of remigrant children in Romania - quantitative aspects. Scientific Annals Of The “Alexandru Ioan Cuza” University, Iaşi. New Series Sociology And Social Work Section, 5(2). http://anale.fssp.uaic.ro/index.php/asas/article/view/83

Lupu, A., L. (2015). Adaptation strategies of the elderly migrants in destination countries – a qualitative analysis. Scientific Annals Of The “Alexandru Ioan Cuza” University, Iaşi. New Series Sociology And Social Work Section, 8(2), 101-112. Retrieved from http://anale.fssp.uaic.ro/ index.php/asas/article/view/83

Marcu, S. (2012). Living across the Borders: The Mobility Narratives of Romanian Immigrants in Spain. Romanian Journal of European Affairs, 12(3). DOI:

Mărginean, I. (2016). Mişcarea naturală a populaţiei. România în contextul statelor membre ale Uniunii Europene, Calitatea Vieţii, 27(2), 118–126.

Matichescu, M. L., Bica, A., Ogidescu, A. S., Lobonț, O. R., Moldovan, N. C., Iacob, M. C., Roșu, S. (2015). The Romanian migration: development of the phenomenon and the part played by the immigration policies of European countries. Revista de Cercetare si Interventie Sociala, 50, 225-238.

Merciu, G., L. (2015). Recent migration dynamics in Resita city and its area of influence. University Of Craiova Series: Geography, 16, 66-75.

Moraru, A. (2015). Emigration and the future of young generation in Bacau county, Romania, Logos Universality Mentality Education Novelty. Section: Social Sciences, 4(1), 89-100.

Moraru, A., & Munteanu, R. F. (2014). Romania - metamorphosis of a developing country and the long-term impact of migration, CES Working Papers, 6(4), 63-74.

Moraru, A., Munteanu, R. F., & Muntele, I. (2015). Emigration and gender in Bacau and Vaslui counties. Analele Universitatii din Oraden-Seria Geografie, 25(1), 39-45.

Moraru, A. & Muntele, I. (2015). Emigration and its geodemographic impact in Slănic Moldova city of Bacau county, Studia Ubb Geographia, 60(1), 81-96.

Moraru, A. & Munteanu, R. F. I. (2015). Workforce deruralization” - a consequence of migration with implication over agriculture, Lucrări Ştiinţifice, 58(2), 277-280.

Nedelcu, D. E. (2015). Romanian young people’s perception regarding the dynamics and effects of international migration in the globalization era. Romanian Review of Social Sciences, 8, 1-18.

Nemenyi, A. (2012). International Migration for Work-Consequences for the Families Who Remain at Home (The Case of Romania). Journal of Population Ageing, 5(2), 119–134. DOI:

Păduraru, M. E. (2014). Romania – emigration’s impact on families and children. Journal of Community Positive Practices, 14(1), 27-36.

Pantea, M. C. (2012). From ‘Making a Living’ to ‘Getting Ahead’: Roma Women's Experiences of Migration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 38(8), 1251-1268. DOI: 10.1080/1369183X.2012.689185

Pantea, M. C. (2013). Social ties at work: Roma migrants and the community dynamics, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 36(11), 1726-1744. DOI: 10.1080/01419870.2012.664282

Pașca, C. S. & Pop, A. L. (2016). Factors influencing Romanian students to study abroad. Review of Economic Studies and Research Virgil Madgearu 9(1), 113-130. https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=343671

Pașca, C. S. & Pop, A. L. (2016). Monetary remittance – Romania case study. The Journal Contemporary Economy, 1(3), 50-60.

Pauna, C. B., & Heins, F. (2012). Migratory flows and their demographic and economic importance in the Romanian regions. An analysis with special reference to the North-East and South-East Regions, 52nd Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Regions in Motion - Breaking the Path", 21-25 August 2012, Bratislava, Slovakia.

Petrea, D., & Hojda, V. (2013). Current Trends and Spatial Implications of Labour Force Migration from the Upper Basin of Vişeu River, Romania. Journal of Settlements and Spatial Planning, 2, 353-358. http://jssp.reviste.ubbcluj.ro/abstracte/abs23JSSPSI022013.html

Petroff, A. (2016). Turning points and transitions in the migratory trajectories of skilled Romanian immigrants in Spain. European Societies, 18(5), 438-459.

Popa, N. L. (2016). Grasping Parental Behaviors through the Eyes of Romanian Adolescents Affected by Parental or Family Migration. Rivista Italiana di Educazione Familiare 11(2), 71-80. http://www.fupress.net/index.php/rief/article/view/19522

Porumbescu, A. (2012). East European Migration Patterns Romanian emigration. Revista de Stiinte Politice, 35, 268-274.

Preda, M. C. (2015). Correlation of supply and demand on labor market in rural areas of Romania as a solution for development. Competitiveness of Agro - Food and Environmental Economy, 259-265. Retrieved from http://www.cafee.ase.ro/wp-content/upload/2015edition/file2015(29).pdf

Quffa, W. A. (2014). The effects of international migration on post Decembrist Romanian society. Revista de Stiinte Politice; Craiova 42, 238-250. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/D2u96u

Rentea, G. C. (2015). Governmental Measures Supporting the Return and the Reintegration of Romanian Migrants. Social Work Review/Revista de Asistenta Sociala, 14(2), 127-137. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/zV3Wn1

Sănduleasa, B., & Matei, A. (2015). Effects of Parental Migration on Families and Children in Post-Communist Romania. Revista de Stiinte Politice, 46, 196-207. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/8LXpi3

Şerb, D., E., & Cicioc, N. (2014). The employment rate in Romania and its impact on the migration phenomenon based on quantitative methods, Revista Academiei Forţelor Terestre, 19(4), 397.

Sîrca, V. (2013). Social and Economic Factors of Romanian External Migration. Preliminary Statistical Analysis: Comparison between the Counties of Cluj and Suceava. Romanian Journal of Population Studies; Cluj-Napoca, 7(1), 47-73. Retrieved from https://goo.gl/us8Twm

Sîrca, V. (2014). Migraţia românească post decembristă: focus grup cu specialişti, An. Inst. de Ist. „G. Bariţiu” din Cluj-Napoca, Series Humanistica, tom. 12, 65–95.

Stan, S., & Erne, R. (2014). Explaining Romanian Labor Migration: From Development Gaps to Development Trajectories, Labor History, 55(1), 21-46. DOI: 10.1080/0023656X .2013.843841

Stanciu, I., D. (2015). Changes on the Wedding Ceremony as an Effect of Migration. A Rural Community from Braşov County. Romanian Journal of Population Studies, 2, 123-140. Retrieved from https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=303301

Șteliac, N. (2014). The Romanian Migration between Official and Unofficial. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 5 6(1), 227-238. Retrieved from https://ijbssnet.com/journals/Vol_5_ No_6_1_May_2014/26.pdf

Stoica, I. (2012). External migration – a developmental tool for Romania. Between opportunity and risk, Impact Strategic, 1, 108-119. Retrieved from https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=113765

Stoica, M. M. (2015). Youth perceptions on the political and economic future of Romania in a global world. Reasons for migration. Interdisciplinary Management Research, 11, 1089-1094. Retrieved from https://ideas.repec.org/a/osi/journl/v11y2015p1089-1094.html

Stoicovici, M. (2012). România ca ţară de origine, de tranzit şI de destinaţie a migranţilor. Revista Română de Sociologie,, serie nouă, anul, 23(5–6), 429–443. Retrieved from http://www.revistadesociologie.ro/pdf-uri/nr.5-6-2012/06-MStoicovici.pdf

Török, I. (2014). From growth to shrinkage: The effects of economic change on the migration processes in rural Romania. Landbauforsch · Appl Agric Forestry Res, 3/4(64), 195-206.

Troc, G. (2012). Transnational migration and Roma self-identity: two case studies. Studia Universitatis Babes-Bolyai-Sociologia, 2, 77-100. Retrieved from https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=90185

Vîlcea, C., Avram, S., & Iordache, C. (2013). Trends of external migrations in South West Oltenia Development Region. Revista de Stiinte Politice; Craiova 39, 77-86. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/openview/264df8b320cde7f5887ada2b3794de59/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=51702

Vlase, I. (2012). Gender and Migration-Driven Changes in Rural Eastern Romania. Migrants’ Perspectives. International Review of Social Research, 2(2), 21-38.

Zimmer, Z., Rada, C., & Stoica, C., A. (2014). Migration, Location and Provision of Support to Older Parents: The Case of Romania. Journal of Population Ageing, 7(3), 161–184.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

27 June 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-948-1

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

1

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-161

Subjects

Business, management, behavioural management, macroeconomics, behavioural science, behavioural sales, behavioural marketing

Cite this article as:

Zodian*, Ș. A. (2017). A Comprehensive Literature Review of Romanias Rural Migration to Europe, 2010-2016. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), Business & Economics - BE-ci 2017, vol 1. European Proceedings of Multidisciplinary Sciences (pp. 141-161). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epms.2017.06.14