Abstract

This study examines the relationship between attitudes and participation in Adult Education and Training (AET) among a representative sample of adults in the Czech Republic. While previous research has explored sociopsychological factors related to AET participation, the direct impact of attitudes on overall participation remains understudied. Using a representative sample of adults (n = 1,200), this study employs a three-factorial model of attitudes towards AET (AtoALE) to investigate the influence of attitudes on the likelihood of AET participation. Structural equation modeling reveals that adults' attitudes significantly predict participation in AET. Our findings indicate that attitudes towards AET have a substantial impact on participation, and are consistent with earlier studies conducted on smaller non-representative samples. Notably, positive attitudes towards organised learning emerge as a crucial factor for participation. Furthermore, our results demonstrate that attitudes towards AET, as proposed by the three-factorial model, are not equal in significance, with emotional associations connected with AET playing a pivotal role. These findings support the notion that attitudes towards AET are deeply embodied and gradually developed over time. In conclusion, we recommend that future research consider both socioeconomic and sociopsychological factors to enhance our understanding of AET participation, expanding the explanatory power of existing models.

Keywords: Adult education and training, attitudes, participation in organised learning, lifelong learning, structural equation modeling

Introduction

According to the last UNESCO's Global Report on Adult Learning and Education (GRALE V.), participation in (AET) and inequality to access to educational opportunities for adults have remained one of the central challenges of lifelong learning (UNESCO, 2022, p. 25).

In recent years, many scholars have done much to understand the structural layers of participation in AET. In this regard, they have explored the role of various institutional features that affect not only the level of participation in a particular country (Desjardins, 2017, 2020, 2023; Desjardins & Ioannidou, 2020; Ioannidou & Parma, 2022; Rubenson, 2018; Rubenson & Desjardins, 2009; Saar et al., 2013, 2023) but also related inequality among different social groups (Blossfeld et al., 2020; Dämmrich et al., 2014; Green et al., 2015; Hovdhaugen & Opheim, 2018; Lee, 2018; Lee & Desjardins, 2021; Van Nieuwenhove & De Wever, 2021), especially those who face various obstacles regarding their access to AET (Cabus et al., 2020; Iñiguez-Berrozpe et al., 2020).

Despite advances, these works often lack an explicit empirical measure of different socio-psychological factors (beliefs, attitudes, or various forms of motivation) linked to participation in AET. According to established theory, socio-psychological constructs are important for explaining participation as they represent cognitive constructs that are close to the decision-making of actors (Boeren, 2016, 2017, 2023; Kyndt et al., 2013a, 2013b; Lavrijsen & Nicaise, 2017). For this reason, the presented study is directly focused on the relationship between one of the sociopsychological factors of participation and AET.

Participation in AET

We understand AET in line with current international discourse (CEDEFOP, 2008; Eurostat, 2016a, 2016b; UNESCO, 2020) as both Formal Adult Education (FAE) and Non-formal Adult Education (NFE) learning activities. While FAE is institutionalised, intentional and planned through public organisations and recognised private bodies that constitute the formal education system of a country, NFE involves structured activities that usually do not result in official certification, according to ISCED (2011). This type of learning includes all organised and planned development activities, such as courses, workshops, and private lessons or training in the workplace. NFE also includes both job-oriented (vocational) as well as non-job-oriented learning.

Numerous authors, including Albert et al. (2010), Boeren (2016), Boeren et al. (2017), Markowitsch and Hefler (2019), and policy documents such as from OECD (2019, 2020), or UNESCO (2022), contend that adult participation in AET contributes to economic development and social inclusion. This participation also benefits individuals by enhancing their qualifications and skills, improving or securing their position in the labour market, and enhancing their well-being (Schuller & Desjardins, 2010). Studies have also shown that adults who participate in AET exhibit higher levels of civic engagement (Iñiguez-Berrozpe et al., 2020) and report better overall quality of life (Field, 2012; Sabates & Hammond, 2008; Schuller & Desjardins, 2010), even in areas unconnected to the workplace. Therefore, it is a significant policy objective for national governments (MYES, 2020), the EU (EC, 2021; CEDEFOP, 2018), UNESCO (2020, 2022), and OECD (2019) to encourage high and equal participation of adults from all socio-demographic groups, especially for those who participate the least.

The level of participation in AET is typically determined by measuring an individual's involvement in any type of formal or non-formal learning activity within the past year. This is applicable to adults between the ages of 25 and 64 years old (Eurostat 2016a, 2016b) who are usually undergoing any kind of post-compulsory training – FAE or NFE. Similarly, the same approach has been used in this study to measure participation levels (see below).

Attitudes and participation in AET

In this article, we define attitudes as everyday opinions and emotions that take the form of normative perspectives on a particular topic (e.g., AET). These views are evaluative, rather than descriptive, and can implicitly or explicitly involve cultural meanings as positive or negative, good or bad, appropriate or inappropriate (Eagly & Chaiken, 2005; Procter, 2008). The significance of attitudes lies in their ability to influence both individuals (Ajzen & Fishbein, 2014) and social groups (Fazio & Olson, 2003). In other words, they serve as a compass for individuals as to whether a particular behaviour or object is appropriate or valuable.

The way adults view AET plays a crucial role in their decision-making process when it comes to participating in educational and training activities. According to various scholars (Boeren, 2016, 2017, 2023; Kalenda et al., 2023; Kyndt et al., 2013a, 2013b; Lavrijsen & Nicaise, 2017), having a positive perception of lifelong learning, viewing participation as beneficial or valuable, and associating learning with positive emotions, tends to make adults more receptive to participating. Conversely, if their attitudes are predominantly negative, they are more likely to be hesitant about participation.

Our understanding of attitudes has been influenced by Lizardo's (2017) triadic model of culture, which has helped us develop a three-factor model of attitudes towards AET (Kalenda et al., 2023). Based on this framework, we have proposed three distinct types of attitudes that reflect particular everyday normative opinions or emotional associations that shape perspectives on AET. These include:

(1) (i.e. personal declarative dimension) involve their daily assessments of its usefulness and expectations for lifelong learning. This may include whether adults believe they need to pursue FAE at some point in their lives or if they view further organised learning as a beneficial activity for personal growth.

(2)(i.e., declarative public dimension) include normative perspectives on the shared meanings of continuous learning. These attitudes assess institutions and key narratives related to adult education, and cover not only the evaluation of educational opportunities but also equal access to AET and its social roles. Its primary focus is on whether AET is perceived as an established social way to enhance individuals' earnings, job prospects, and social inclusion.

(3) The final type of attitude in the proposed model pertains to normative (personal aspects of non-declarative dimension). It focuses on both positive and negative emotions associated with adult education. These emotions are significant because they reflect implicit ideas of organised learning for adults that, unlike the preceding two types, are learned much slowly, and they are deeply embodied.

In summary, we argue that attitudes towards AET are complex and encompass various dimensions. They represent individuals' perceptions and emotional associations towards lifelong learning and can influence their participation. These attitudes can be measured through statements that express evaluative opinions, reflecting cultural beliefs that consider AET as either individually favourable or unfavourable, socially beneficial or unhelpful, and associated with positive or negative emotions.

Problem Statement

Although some of the sociopsychological aspects of participation in AET, like motivation, or perceived barriers, have been investigated before (Blunt & Yang, 2002; Boeren, Holford, et al., 2012; Boeren, Nicaise, et al., 2012; Boshier 1971; Cross 1981), a deeper examination of attitudes is still needed. Surveys that specifically target attitudes have not been conducted with representative samples of adults (Bennett, 2016; Blunt & Yang, 2002; Darkenwald & Hayes, 1988; Hayes & Darkenwald, 1990; Lavrijsen & Nicaise, 2017), making it difficult to establish a clear link between attitudes to lifelong learning and AET involvement. Furthermore, there has not been a systematic exploration of how attitudes impact the participation of adults in organised adult learning in the Czech Republic. Previous research in this country has primarily focused on comparing attitudes between those who do and do not participate in AET (Kalenda et al., 2023), motives for non-involvement in AET (Kalenda & Kočvarová, 2022a), barriers to AET (Kalenda et al., 2022) or socioeconomic factors contributing to participation in organised learning for adults (Kalenda & Kočvarová 2022b; Vaculíková et al., 2021).

Research Questions

Following the previous discussion, we have addressed three interrelated research questions that were previously identified as a research gap. These questions include: (1) Whether attitudes towards AET have an impact on participation in AET? (RQ1);(2) To what extent attitudes towards AET can predict the variability of participation in AET? (RQ2), and (3) How do different types of attitudes, based on the triadic model of culture, affect participation in AET? (RQ3).

Purpose of the Study

The aim of the study is to explore the link between attitudes towards AET and participation in AET among a representative sample of adults in the Czech Republic. This study aims to demonstrate: (1) how attitudes affect participation in AET in the Czech Republic (as outlined in RQ1), (2) how attitudes can explain some of the participation in AET (see RQ2), and (3) which attitudes have the greatest impact on participation in AET among Czech adults (see RQ3).

Research Methods

Research sample

Our quantitative research used a representative stratified random sample of 1,200 individuals aged 25 to 69 years, reflecting the gender, education, and region ratio of the overall Czech population. The data was collected in the Czech Republic during September and October 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, using the Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI) method by a professional agency. Throughout the survey process, ethical principles of research were emphasised, particularly anonymity, as per the ICC/ESOMAR International Code (2022). Our data have no missing values, and Table 1 shows the basic socio-demographic characteristics of the sample.

Measures

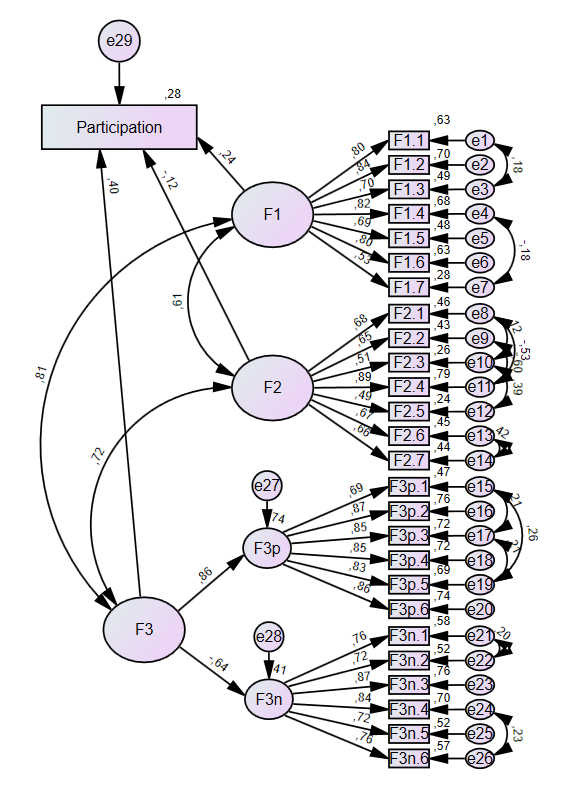

In our research, we utilised the “Attitudes toward adult learning and education questionnaire” (AtoALE). This questionnaire consists of three batteries of items that were created following the theoretical model introduced earlier (Kalenda et al., 2023). Each battery of items focuses on one of the three forms of attitudes discussed above: Factor 1 (F1): (Personal declarative dimension); Factor 2 (F2):(Public declarative dimension); and Factor 3 (F3):(Personal non-declarative dimension), which is further divided into F3p (positive emotions) and F3n (negative emotions).

The AtoALE research tool comprises 26 items and uses a 6-point Likert scale, where 1 indicates strong disagreement, and 6 indicates strong agreement (see Table 2). The tool satisfies the standard statistical parameters for measurement quality (x2 = 1555.221; df = 282; CFI = 0.937; TLI = 0.928; RMSEA = 0.061). All factors and the complete tool are dependable. Results of Cronbach's α show a value of 0.895 for F1, 0.835 for F2, 0.929 for F3p, 0.907 for F3n, and 0.830 for the Complete model. Detailed information regarding the construct validity and reliability of AtoALE is available in Kalenda et al. (2023). Similar to major international surveys on lifelong learning, such as the(AES) and Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), participation in AET is measured as the involvement of adults in any FAE and NFE in the twelve months before the survey.

Analysis

To better understand why some individuals participate in AET while others do not, we used (SEM) to examine the relationship between attitudes towards AET and participation in organised learning. In this model, participation was the dependent variable, while attitudes towards AET were the independent variables. We ensured that the model met standard measurement quality parameters (x2 = 1657.193; df = 305; CFI = 0.935; TLI = 0.925; RMSEA = 0.061), and all regression weights, intercepts, covariances, and variances were found to be statistically significant at a level of 0.01.

We conducted our analysis using IBM SPSS 27, and used IBM SPSS Amos 27 for SEM. To calculate reliability, we used JASP 0.16.2.0, which allowed us to calculate not only Cronbach's α, but also McDonald's ω and Gutmann's λ6.

Findings

The results from our SEM analysis are presented in Figure 1. It is evident that the total explained variance of participation in AET is 28% by using a three-factorial model of attitudes. All of the proposed factors of the theoretical model have a positive correlation among each other. Their impact on the level of participation is mostly indicating that more people tend to participate in AET when they agree with individual items, except for factor F2 () and sub-factor F3n (negative) which has reversely formulated items. In this regard, negative emotional associations with AET are related to non-participation. The strength of the direct effect of F1 () is .24, F2 () is .12 (the weakest), and F3 () is .40 (the strongest).

Conclusion

Our research has found that attitudes towards AET have a substantial impact on participation, even when measuring attitudes for both FAE and NFE on a representative sample of adults aged 25 to 69. These results align with previous research on smaller non-representative samples conducted by Bennett (2016), Blunt & Yang (2002), Darkenwald & Hayes (1988), Hayes & Darkenwald (1990), and Lavrijsen & Nicaise (2017). It is essential to have a positive attitude towards organised learning as a crucial factor for participation.

In addition, research has shown that attitudes towards AET can significantly predict participation in AET. Although models that explain participation based on socioeconomic factors can account for 19 to 35% of the variability (Blossfeld et al., 2020; Dämmrich et al., 2014; Kalenda & Kočvarová, 2022b, Kalenda et al., 2022), our model has a similar explanatory power, accounting for 28% of the explained variation. Therefore, we strongly recommend that future research should consider both socioeconomic and sociopsychological factors to expand our understanding and explanation of participation in AET.

Lastly, our research indicates that not all types of attitudes towards AET, as per our triadic model, carry the same weight. Some hold more significance than others. Specifically, emotional associations connected with AET (F3) appear to be crucial. This is not only because they have the greatest impact on overall participation, but also because they are closely linked to the other two forms of attitudes. Therefore, our findings support the previous theoretical assumption that attitudes towards AET are deeply ingrained in individuals (Kyndt et al., 2013b, 2013b; Lavrijsen & Nicaise, 2017; Van Nieuwenhove & De Wever, 2021), and have gradually developed over time rather than being a by-product of current public discourse.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analysed in this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of Conflicts Interests

The author(s) declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship or publication of this article.

Funding

This article was written with the financial support of the project “Personality and employment factors in adult education: Measuring participation and non-participation in non-formal education” from the Faculty of Humanities, Tomas Bata University in Zlín.

Ethics Statement

Data collection and data analysis follow the ethical principles of research respecting the ICC / ESOMAR International Code (ESOMAR, 2022). A principle of anonymity was followed according to which participants remained anonymous to each other and to the research team. Emphasis was put on voluntary participation and comprehension of informed consent. Principle of anonymity remaining participants anonymous and to the researchers themselves throughout the study emphasised voluntary participation and comprehension of informed consent. Participants were informed about the aims of the research and that the given information would be treated confidentially. Grant project reviewers evaluated the grant proposal with respect to ethical implications and assured the safety and rights of participants.

References

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (2014). The influence of attitudes on behaviour. In D. Albarracin, B. T. Johnson, & M. P. Zanna, (Eds.). The Handbook of Attitudes (pp. 173–221). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Albert, C., García-Serrano, C., & Hernanz, V. (2010). On-the-job Training in Europe: Determinants and Wage Returns. International Labour Review, 149(3), 315–341.

Bennett, A. R. (2016). Attitudes Toward Adult Education Among Adult Learners Without a High School Diploma or GED. Available at Graduate Theses and Dissertations.http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6468

Blossfeld, H.-P., Kilpi-Jakonen, E., Vono de Vilhena, D., & Buchholz, S. (2020). Is there a Matthew effect in adult learning? Results from a cross-national comparison. In J. Schrader, A. Ioannidou, & H.-P. Blossfeld (Eds.), Monetäre und nichtmonetäre Erträge von Weiterbildung – Monetary and nonmonetary effects of adult education and training. Edition ZfE, Vol. 7 (pp. 51–74). Wiesbaden, Germany: VS.

Blunt, A., & Yang, B. (2002). Factor Structure of the Adult Attitudes Toward Adult and Continuing Education Scale and its Capacity to Predict Participation Behavior: Evidence for Adoption of a Revised Scale. Adult Education Quarterly, 52(4), 299–314.

Boeren, E. (2016). Lifelong Learning Participation in a Changing Policy Context. An Interdisciplinary Theory. Palgrave Macmillan.

Boeren, E. (2017). Understanding adult lifelong learning participation as a layered problem. Studies in Continuing Education, 39(2), 161–175.

Boeren, E. (2023). Conceptualizing Lifelong Learning Participation – Theoretical Perspectives and Integrated Approaches. In M. Schemman (Ed.), Internationales Jahrbuch der Erwachsenenbildung / International Yearbook of Adult Education 2023 (pp. 17–31).

Boeren, E., Holford, J., Nicaise, I., & Baert, H. (2012). Why do adults learn? Developing a motivational typology across 12 European countries. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 10(2), 247-269.

Boeren, E., Nicaise, I., Roosmaa, E. L., & Saar, E. (2012). Formal Adult Education in the spotlight: Profiles, motivation, and experiences of participants in 12 countries. In S. Riddel, J. Markowitsch, & E. Weeden (Eds.), Lifelong learning in Europe: Equality and efficiency in balance (pp. 63–86). Polity Press.

Boeren, E., Whittaker, S., & Riddell, S. (2017). Provision of Seven Types of Education for Disadvantaged Adults in Ten Countries: Overview and Cross-Country Comparison. ENLIVEN Report, Deliverable No. 2.1. https://h2020enliven.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/enliven-d2-1.pdf

Boshier, R. (1971). Motivational orientations of adult education participants: a factor analytic exploration of Houle’s typology. Adult Education, 21(2), 3–26.

Cabus, S., Ilieva-Trichkova, P., & Štefánik, M. (2020). Multi-layered perspective on the barriers to learning participation of disadvantaged adults. Zeitschrift für Weiterbildungsforschungm, 43(2), 169–196.

CEDEFOP. (2008). Terminology of European education and training policy-a selection of 100 key terms CEDEFOP. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

CEDEFOP. (2018). Insights into skill Shortages and skill mismatch. Learning from Cedefop´s European skills and job survey. Luxembourg: Publications Office. Cedefop reference series; No 106.

Cross, P. K. (1981). Adults as Learners. Increasing Participation and Facilitating Learning. Jossey-Bass.

Dämmrich, J., Vono, D., & Reichart, E. (2014). Participation in adult learning in Europe: The impact of country-level and individual characteristics. In H.-P. Blossfeld, E. Kilpi-Jakonen, D. Vono de Vilhena, & S. Buchholz (Eds.), Adult learning in modern societies: Patterns and consequences of participation from a life-course perspective (pp. 25–51). Edward Elgar.

Darkenwald, G. G., & Hayes, E. R. (1988). Assessment of adult attitudes toward continuing education. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 7(3), 197–204.

Desjardins, P. (2020). PIAAC Thematic Report on Adult Learning. OECD Education Working Paper No. 223. OECD.

Desjardins, R. (2017). Political Economy of Adult Learning Systems. Comparative Study of Strategies, Policies, and Constraints. Bloomsbury.

Desjardins, R. (2023). Lifelong Learning Systems. In K. Evans, J. Markowitsch, W. O. Lee, & M. Zukas (Eds.) Third International Handbook of Lifelong Learning. Springer International Handbooks of Education (pp. 353–374). Springer.

Desjardins, R., & Ioannidou, A. (2020). The political economy of adult learning systems—some institutional features that promote adult learning participation. Zeitschrift für Weiterbildungsforschung, 43, 143–168.

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (2005). Attitude research in the 21st century: The current state of knowledge. In D. Albarracin, B. T. Johnson, & M. P. Zanna, (Eds.), The Handbook of Attitudes (pp. 743–767). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

EC. (2021). Towards a sustainable Europe by 2030. European Commission. Luxembourg: Publication Office. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/towards-sustainable-europe-2030_en

ESOMAR. (2022). ICC/ESOMAR International Code. https://esomar.org/code-and-guidelines/icc-esomar-code

Eurostat. (2016a). 2016 AES manual. Available from https://circabc.europa.eu/sd/a/700a220d-33dc-42d4-a5c4-634c8eab7b26/2016%20AES%20MANUAL%20v3_02-2017.pdf

Eurostat. (2016b). Classification of learning activities manual. Publications Office of the European Union.

Fazio, R. H., & Olson, M. A. (2003). Attitudes: Foundations, functions, and consequences. In M. A. Hogg, & J. Cooper (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of social psychology (pp. 139–160). Sage.

Field, J. (2012). Is lifelong learning making a difference? Research-based evidence on the impact of adult learning. In D. Aspin, J. Chapman, K. Evans & R. Bagnall (Eds.), Second international handbook of lifelong learning (pp. 887–897). Springer.

Green, A., Green, F., & Persiero, N. (2015). Cross-country variation in adult skills inequality: Why are still levels and opportunities so unequal in Anglophone countries? Comparative Education Review, 59(4), 595–619.

Hayes, E., & Darkenwald, G. G. (1990). Attitudes toward adult education: An empirically-based conceptualization. Adult Education Quarterly, 40(1), 158–168.

Hovdhaugen, E., & Opheim, V. (2018). Participation in adult education and training in countries with high and low participation rates: Demand and barriers. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 37(5), 560–577.

Iñiguez-Berrozpe, T., Elboj-Saso, C., Flecha, A., & Marcaletti, F. (2020). Benefits of Adult Education Participation for Low-Educated Women. Adult Education Quarterly, 70(1), 64–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741713619870793

Ioannidou, A., & Parma, A. (2022). Risk of Job Automation and Participation in Adult Education and Training: Do Welfare Regimes Matter? Adult Education Quarterly, 72(1), 84–109.

ISCED. (2011). International standard classification of education (ISCED) 2011. UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

Kalenda, J., & Kočvarová, I. (2022a). Why do they not participate? Reasons for non-participation in adult learning and education from the viewpoint of self-determination theory. (RELA) Journal of European Research of Learning and Education of Adults. Pre-published, 1-16.

Kalenda, J., & Kočvarová, I. (2022b). Participation in non-formal education in risk society. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 41(2), 146-167.

Kalenda, J., Boeren, E., & Kočvarová, I. (2023). Exploring attitudes towards adult learning and education: group patterns among participants and non-participants, Studies in Continuing Education,

Kalenda, J., Kočvarová, I., & Vaculíková, J. (2022). Barriers to Participation of Low-educated Workers in Non-formal Education. Journal of Education and Work. Pre-published, 1-16.

Kyndt, E., Govaerts, N., Keunen, L., & Dochy, F. (2013a). Examining the learning intentions of low-qualified employees: a mixed method study. Journal of Workplace Learning, 25(3), 178–197.

Kyndt, E., Raes, E., Dochy, F., & Janssens, E. (2013b). Approaches to learning at work: Investigating work motivation, workload and choice independence. Journal of Career Development, 40(4), 271–291.

Lavrijsen, J., & Nicaise, I. (2017). Systemic obstacles to lifelong learning: the influence of the educational system design on learning attitudes. Studies in Continuing Education, 39(2), 176–196.

Lee, J. (2018). Conceptual foundations for understanding inequality in participation in adult learning and education (ALE) for international comparisons, International Journal of Lifelong Education, 37(3), 297–314.

Lee, J., & Desjardins, R. (2021). Changes to adult learning and education (ALE) policy environment in Finland, Korea and the United States: implications for addressing inequality in ALE participation, Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 51(2), 221–239.

Lizardo, O. (2017). Improving Cultural Analysis: Considering Personal Culture in its Declarative and Nondeclarative Modes. American Sociological Review, 82(1), 88–115.

Markowitsch, J., & Hefler, G. (2019). Future Developments in Vocational Education and Training in Europe, Report on reskilling and upskilling through formal and vocational education training. Seville: European Commission.

MEYS. (2020). Strategie vzdělávací politiky do roku 2030+. Ministerstvo školství, mládeže a tělovýchovy.

OECD. (2019). Getting Skills Right: Future-ready adult learning systems. OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD. (2020). OECD Skills Strategy Slovak Republic: Assessment and Recommendations. OECD Skills Studies. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Procter, M. (2008). Measuring attitudes. In N. Gilbert (Ed.), Researching Social Life (pp. 105–122). Sage.

Rubenson, K. (2018). Conceptualising Participation in Adult Learning and Education. Equity Issues. In M. Milana, S. Webb, J. Holford, R. Waller, & P. Jarvis (Eds.), The Palgrave International Handbook on Adult and Lifelong Education and Learning (pp. 337–357). Palgrave.

Rubenson, K., & Desjardins, R. (2009). The impact of welfare state requirements on barriers to participation in adult education: A bounded agency model. Adult Education Quarterly, 59(3), 187–207.

Saar, E., Roosalu, T., & Roosmaa, E. L. (2023). Lifelong Learning for Economy or for Society: Policy Issues in Post-Socialist Countries in Europe. In K. Evans, W. O. Lee, J. Markowitsch, & M. Zukas (Eds.), Third International Handbook of Lifelong Learning (pp. 523–548). Springer International Handbooks of Education,

Saar, E., Ure, O. B., & Holford, J. (Eds.). (2013). Lifelong Learning in Europe. National Patterns and Challenges. Edward Elgar.

Sabates, R., & Hammond, C. (2008). The impact of lifelong learning on happiness and well-being. Leicester: National Institute for Adult and Continuing Education.

Schuller, T., & Desjardins, R. (2010). The wider benefits of adult education. In P. Peterson, E. Baker, & B. McGaw (Eds.), International encyclopaedia of education (pp. 229–233). Elsevier.

UNESCO. (2020). Embracing a culture of lifelong learning. Contribution to the Futures of Education initiative. UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning.

UNESCO. (2022). GRALE V. 5th Global Report on Adult Learning and Education. citizenship education: empowering adults for change; executive summary Hamburg: UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning. Dostupné z: https://uil.unesco.org/adult-education/global-report/5th-global-report-adult-learning-and-education-citizenship-education-0

Vaculíková, J., Kalenda, J., & Kočvarová, I. (2021). Hidden gender differences in formal and non-formal adult education. Studies in Continuing Education, 43(1), 33-47.

Van Nieuwenhove, L., & De Wever, B. (2021). Why are low-educated adults underrepresented in adult education? Studying the role of educational background in expressing learning needs and barriers. Studies in Continuing Education, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2020.1865299

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

26 December 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-965-8

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

4

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-109

Subjects

Education, educational psychology, pedagogy, positive pedagogy, special education, second language teaching

Cite this article as:

Kalenda, J., Kočvarová, I., & Karger, T. (2023). Impact of Attitudes on Participation in Adult Education and Training. In A. Güneyli, & F. Silman (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2023: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 4. European Proceedings of International Conference on Education and Educational Psychology (pp. 20-31). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epiceepsy.23124.2