Abstract

Social work is an emotionally demanding profession, in which workers must reflect and regulate emotions. Students are not prepared for this emotion management, which often leads to unauthenticity. The study’s research questions refer to the relationships between authenticity, self-regulation and reflexivity for Czech students of social work. Therefore, the article‘s aim is to map these relationships between authenticity, self-regulation and reflexivity in Czech social work students and to determine the implications for social work based on these relationships mapping. The data were obtained by quantitative research strategy; specifically by a questionnaire survey, in which 102 sets of questionnaires (including Authenticity Scale, Generalized Expectancy for Negative Mood Regulation Scale and Groningen Reflexion Ability Scale) were obtained by intentional criterion selection. The data were processed by using the Pearson's correlation coefficient, the Krustal-Wallis test and the analysis of variance (ANOVA). The research found that: a) a high degree of reflexivity is associated with a low degree of authenticity; b) a high degree of self-regulation is associated with a low degree of authenticity; c) a high degree of reflexivity is associated with a high degree of self-regulation; and d) the length of practice is related to reflexivity. Therefore, the study concluded that high reflexivity enhances high self-regulation which leads to low authenticity. However, the way that reflexivity is constructed by students of social work is questioned. Social work students seem to view reflexivity through the technical rationality. Therefore, it is necessary to strengthen holistic reflexivity of students, which can strengthen their authenticity in practice.

Keywords: Authenticity, reflexivity, self-regulation, social work, education

Introduction

The social work practice naturally evokes emotions in social workers since they witness emotionally intense situations (Barlow & Hall, 2007). Also, working with persons who require some support from a social worker in dealing with their own (strong) emotions is a common phenomenon in social work (Ikenbuchi & Rasmunssen, 2014). The performance of social work thus becomes emotionally demanding and stressful, especially in cases where social workers work with vulnerable children or experience traumatic events with their clients, such as the loss of a loved one (Grant et al., 2014). Stanley and Bhuvaneswari (2016) add that social work is a highly stressful profession precisely, because it involves working with people in stressful life events such as domestic violence, crime experience, loss of housing, etc.

In social work practice, social workers experience situations associated with negative emotions (similarly see Smith, 2010; Stanley & Bhuvaneswari, 2016), but also with joy (Cameron & Jago, 2008). A number of research works deal with the types of feelings that social workers experience in their practice. These research works refer to: pain, shame, guilt, anger, helplessness, anxiety, discomfort, being overwhelmed, worry, isolation, shock, agitation, humiliation, anger, and combinations thereof (Barlow & Hall, 2007). Other research deals with fears in social work, where, for example, Smith (2010) notes that social workers face fears of death, loss of control, separation from the organization they work for, fear of assault, etc. Litvack et al. (2010) categorizes fears in social work into fears and worries about personal safety, fears of harming others, and fears associated with relationships with other professionals/colleagues.

In health and social care, workers are expected to be able to manage their emotions (Grandey et al., 2012). Clients cope with discomfort due to their difficult life situation in which they find themselves and show emotions of fear or anger, which places great demands on helping professionals (Demerouti et al., 2001). At the same time, they are expected to work with their emotions (Brotheridge and Lee (2002) define emotional labour as the management of public expressions of workers’ emotions in line with the organizational rules for expressing emotions. Thanks to emotional labour, emotions are expressed in an appropriate way at appropriate moments and suppressed in all other cases (Banks, 2012).) in the sense of expressing interest, fear, fondness, and suppression of frustration and anxiety (Mann, 2005); which may lead to alienation from the true self, inauthenticity and emotional fatigue (Vannini & Franzese, 2008). Workers are forced to suppress anger and respond positively to clients’ negative emotions, meaning that they must fabricate emotional expressions (Diefendorff et al., 2008; Rupp & Spencer, 2006). Expressing emotions and is viewed as unprofessional in the social and health service professions (Emotional management (rules of conduct) in an organization may not always lead to inauthenticity; it may help some employees cope with emotionally intense situations and maintain a role distance (Sloan, 2007). ) (Henderson, 2001; Lewis, 2005). Therefore, a person is therefore always balancing between authenticity and acceptance by others (Vannini & Franzese, 2008).

In the Czech educational context of social work, the educational setting, which is focused on meeting the clients’ needs in a situation where the workers’ needs (in order to carry outare rather neglected, seems to be problematic. In the context of the above, this paper aims to map the relationships between authenticity, self-regulation and reflexivity among Czech students of social work and based on these relationships to determine the implications for social work.

Problem Statement

Authenticity can be defined as: the condition of (achieving the individual’s full potential) (Rogers, 1965); an individual’s own perception, which leads to the experience (lack of) authenticity (Erickson, 1994);a bipolar continuum, where on the one hand there is a fully authentic being and on the other a fully inauthentic being (Van den Bosch & Taris, 2014); ideal and task (Man interacts with others to strike a balance between ideal and necessity.) (searching for one’s true self) (Johnson, 2007; O’Connor, 2006); the feeling of genuineness to oneself (to one’s self; it is) and to other people (it is); authenticity thus becomes a product of social interaction (Vannini & Franzese, 2008).

Authenticity arises through the reflection of one’s own actions and their subsequent adjustment (Vannini & Franzese, 2008; English & John, 2013). In this context, the reflexivity of a particular individual can be understood as a project of one’s self as a self-determining subject (Elliot, 2001). Gardner (2016) emphasizes the procedural nature of critical reflexivity and says that critical reflexivity is a process that begins with a certain incident, continues with emotions, values, questioning, articulation of values and assumptions, and ends with a change in one’s actions in practice. The human self can thus be considered a certain reflective project, which is continuously revised in the intentions of the opposites of the true and false selves (Giddens, 1991). The perception of incongruence between the internal (true) self and external behaviour leads to a feeling of inauthenticity (Rogers, 1965).

Authenticity offers two dichotomous possibilities for conceptualization: A) authenticity is a stable disposition that does not change over time (see, e.g., Wood et al., 2008); versus: a sense of authenticity arises as a result of congruence between a person and the specific environment in which he or she functions (Van den Bosch & Taris, 2014; Schmidt, 2005); and B); versus (Wood et al., 2008).

Authenticity consists of four components: awareness (recognition of existing polarities), unbiased processing (objectivity in assessing one’s own positive and negative aspects), behaviour (in accordance with one’s own values and self-determination) and relational orientation (truth in close relationships) (Goldman & Kernis, 2002). Authenticity at work has three components: (the degree of truthfulness to one’s self and acting in accordance with one’s own values and beliefs), (subjective experience when one does not know who he/she is) and(fulfilling the expectations of others) (Van den Bosch & Taris, 2014).

In the context of the above-mentioned high expectations made of social and health service workers, it can be generally stated that professions that require working with people place high demands on, which can be understood as control over emotional expression and experience, especially negative emotions and their energy. The act of suppressing emotions costs workers energy. Emotional suppression is thus associated with stress, exhaustion, burnout, and other stressors (see, e.g., Baumeiser et al., 2007; Bono & Vey, 2005; Lee et al., 2010).

Therefore, authenticity can be conceptualized as part of a broader set of self-regulatory efforts that monitors the effects of behaviour on an individual’s self (Leary & Baumeister, 2000). Authenticity is an indicator whether an individual’s behaviour is congruent with his or her general beliefs, attitudes, values, and goals (English & John, 2013). Thus, authenticity can be considered as a product of self-regulation, which reflects a high level of self-determination or a high introjection of the requirements of others, which gives rise to inauthenticity (Forgas et al., 2005).

Boucher (2011) and Grandey et al. (2012) point out the importance of authenticity for human functioning. Lower levels of authenticity are associated with a higher risk of anxiety, depression and perceived stress (Van den Bosch & Taris, 2014). Forgas et al. (2005) state that authenticity promotes mental health, safe attachment to other people and social adjustment. Wood et al. (2008) and Toor and Ofori (2009) point out that authenticity is positively correlated with life satisfaction, self-esteem (similarly Vannini & Franzese, 2008), autonomy, happiness, self-acceptance, personal growth and gratitude in a relationship to others. Ménard and Brinet (2011) expand on a positive correlation between authenticity and well-being (similarly, see also Toor & Ofori, 2009) and authenticity and job satisfaction. Van Horn et al. (2004) add that authenticity reduces emotional exhaustion. Authenticity can also be associated with better work results, performance in work roles and work commitment (Van den Bosch & Taris, 2014). Feelings of inauthenticity lead to problems such as depression or anxiety. Inauthenticity interferes with self-opening and gaining appropriate self-affirmation from others; it can also prevent misunderstandings, lead to interpersonal distance and less satisfaction in social relationships and lower attainment of social support on the part of the individual (Goldman & Kernis, 2002).

Research Questions

In this context our research question was: What are the relationships between authenticity, self-regulation and reflexivity for Czech students of social work?

Purpose of the Study

In relation to the above, the purpose of our article is to map the relationships between authenticity, self-regulation and reflexivity in Czech social work students and to determine the implications for social work based on these relationships mapping.

Research Methods

In the quantitative research strategy that we used, we investigated the relationships between authenticity, self-regulation, and reflexivity in Czech students of social work. We centred our investigation/survey on the relationships between: a) authenticity and selected concepts of social work practice, specifically the abilities of reflexivity and self-regulation; b) age and length of experience and authenticity, self-regulation, and reflexivity. The phenomenon of authenticity and its relations with other concepts of social work practice is yet to be researched in the Czech Republic. Based on the results of foreign research (see e.g. Leary & Baumeister, 2000; Forgas et al., 2005), we assumed the following relationships between individual concepts:

: A high degree of reflexivity ability is associated with a high degree of authenticity.

The high use of self-regulation is associated with a high degree of inauthenticity.

A high degree of reflexivity is associated with a high degree of self-regulation.

There is a relationship between age and the overall score of authenticity, reflexivity, and self-regulation

There is a relationship between the length of experience and the overall score of authenticity, reflexivity, and self-regulation

We used an intentional criterion sampling to select our respondents. The selection criteria were: a) university study of social work at one of the universities in the Czech Republic; b) Bachelor’s degree in social work and enrolment in a follow-up Master’s studies; c) voluntary participation in research. A total of 102 students from four universities took part in the research.

Data were collected using an online questionnaire, which was compiled by combining three existing questionnaires (We refrained from creating a questionnaire of our own design due to: a) obtaining the consent of the authors of foreign inventories to use them; b) unexplored phenomenon of authenticity in the Czech environment and a certain declared intuitiveness of social work practice.) . We used the following sources: a) Authenticity Scale (Wood et al., 2008); b) Generalized Expectancy for Negative Mood Regulation Scale (Catanzaro & Mearns, 1990); c) Groningen Reflexion Ability Scale (Aukes, 2008). The Czech translations of the questionnaires were created on the basis of a double-blind text translation, which translated the English versions of the inventories into Czech, and then back into English. The translations were then edited and consulted with native speakers.

The obtained data were described using descriptive statistics, adjusted for erroneous and missing values, while the accuracy of remote and extreme values was verified and corrected. The following statistical methods were used for data analysis: Pearson’s correlation coefficient, analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Krustal-Wallis test.

As part of the research, we followed the Ethical Principles in Human Research adopted by the American Psychological Association (APA, 2010) and current Czech legislation. All participants were informed about the research objectives and the subsequent data handling.

In relation to the limits of research, it can be stated that we reflect several basic limits: a) social desirability of respondents in relation to the statements; b) an unrepresentative sampling, which prevents the data collected from being generalized; c) the selection of the research sample determined to some extent by self-selection, which does not reflect the difference between the respondents who decided to participate in the research and those who did not decide to participate. Even so, the data provide an interesting insight into the issue of authenticity and its relationships in students of social work.

Findings

A total of 102 social work students (93 women and 9 men) were involved in the research. Two variables were monitored within the research: a) age (in years); b) length of experience (in years). The average age was 29 years. The minimum age was 22 and the maximum age was 52 years. The average length of experience (in years) was 5 years, with the maximum length of experience being 29 years and the minimum length of experience 0 years. The above data served to create categories for further data analysis: (1) age: up to 26 years (n=63); 27 to 39 years (n=18) and over 39 years (n=21); (2) length of experience: experience of less than 1 year (n=24); experience 1 to 5 years (n=50), experience over 5 years (n=28).

As part of the data analysis, the total questionnaire scores were identified for individual respondents (The occurrence of negative statements was taken into account in the calculation of the total scores.) , which are clearly depicted in Table 1.

The subject of our analysis was the correlation of the total questionnaire scores, which was calculated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

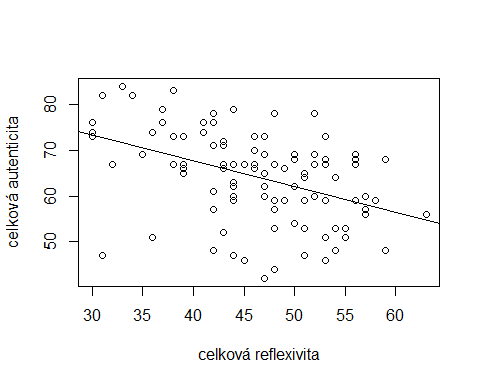

Relationship between the total reflexivity score and total authenticity score

The analysis of the relationship between the total reflexivity score and total authenticity score revealed that(see Figure 1). Pearson’s correlation coefficient was -0.4346422. The null value of a correlation coefficient was rejected (p-value was 2.502e-06).

Source: Authors’ own design

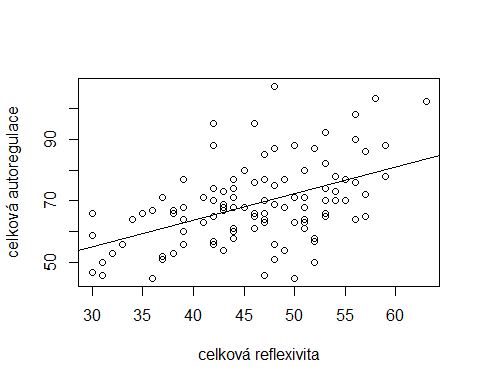

Relationship between the total reflexivity score and total self-regulation score

The analysis of the relationship between the total reflexivity score and total authenticity score revealed that (see Figure 2). Pearson’s correlation coefficient was 0.4852151. The null value of the correlation coefficient was rejected (p-value was 1.18e-07).

Source: Authors’ own design

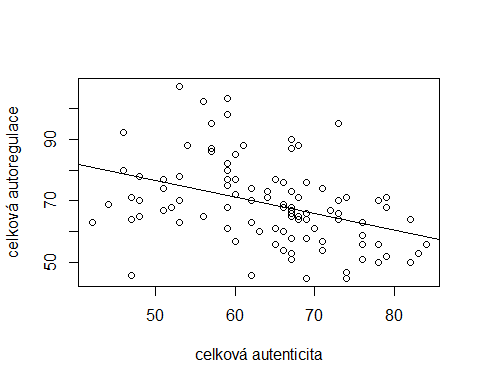

Relationship between the total authenticity score and total self-regulation score

The analysis of the relationship between the total reflexivity score and total authenticity score revealed that(see Figure 3). Pearson’s correlation coefficient was -0.3918029. The null value of the correlation coefficient was rejected (p-value was 2.328e-05).

Source: Authors’ own design

As part of subsequent data analysis, we determined the dependence of the total scores of individual questionnaires on the age of respondents and their length of practice. This dependence was determined using ANOVA (where the null hypothesis about data normality was not rejected) and the Krustal-Wallis test. This analysis did not confirm the relationship between:

- Age category (see above) and total reflexivity score (p-value: 0.1499);

- Age category (see above) and total authenticity score (p-value: 0.6324);

- Age category (see above) and total self-regulation score (p-value: 0.2642);

- Length of practice (see above) and total self-regulation score (p-value: 0.171);

- Length of practice (see above) and total self-regulation score (p-value: 0.05249).

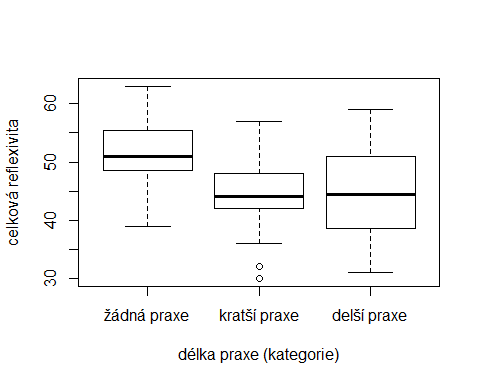

This analysis confirmed the relationship between:

- Length of practice (see Figure 4) and total reflexivity score (p-value: 3.821e-05).

Source: Authors’ own design

Regarding the validity of hypotheses:

A high degree of reflexivity is associated with a high degree of authenticity. The research found that with an increasing total reflexivity score, the total authenticity score decreases. Therefore we can conclude that reflexivity apparently tends to lead to an increase in self-regulation in workers, thus reducing their authentic expression in practice.

A high degree of self-regulation is associated with a high degree of inauthenticity (or a low level of authenticity). The research found that with an increasing total authenticity score, the total self-regulation score decreases.

A high degree of reflexivity is associated with a high degree of self-regulation. The research found that with an increasing total reflexivity score, the total self-regulation score increases.

There is a relationship between age and the total score of authenticity, reflexivity and self-regulation. The relationship between age and total score was not demonstrated in any of the questionnaires. The ability of authenticity, reflexivity and self-regulation is therefore related to variables other than age.

There is a relationship between the length of practice and the total score of authenticity, reflexivity and self-regulation. The relationship between the length of practice and the total score of the questionnaires was demonstrated only in case of reflexivity. Thus, it seems that authenticity and self-regulation are related to other variables in the social work practice (e.g. with the personality of the worker or with the strategies used to perform fine in the practice).

Conclusion

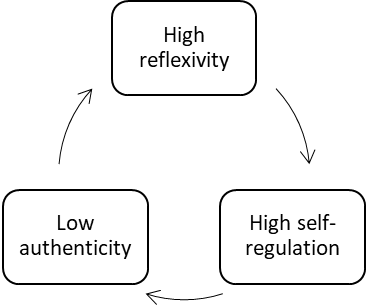

The research found that: a) A high degree of reflexivity is associated with a low degree of authenticity; b) A high degree of self-regulation is associated with a low degree of authenticity; c) A high degree of reflexivity is associated with a high degree of self-regulation; d) The length of practice is related to the degree of reflexivity. Our basic findings can be illustrated by the Figure 5.

Source: Authors’ own design

Thus, high reflexivity reinforces high self-regulation, which leads to low authenticity. However, there is a question of how the reflexivity is constructed by social work students, or in relation to what it is constructed. In relation to the research results and findings on possible views of reflexivity through the lens of the technically conceived self of a social worker or a reflexive professional, we believe that reflexivity is viewed through a technical lens by social work students.

A technically conceived lens is based on the concept of technical rationality, which presupposes an instrumental solution of the problem performed on the basis of scientific theory and techniques. This construct is also based on the assumption that social problems are objective and real and that a social worker is a professionally skilled worker applying an experimentally proven theory into practice (where he/she works with objects rather than subjects). The concept of technical rationality perceives emotions as undesirable, as it is based on objectivism, which presupposes the collection of unambiguous and unquestionable data that can be compared with the expected norm (similarly see Navrátil, 2014). In this context, we can assume that social workers apply reflection in a sense whether they act in accordance with the rules, procedures and requirements of the organization (one’s responsibility toward organization) and not in the sense that they apply reflection in relation to the social construction of reality existing in a particular contextual framework, and it seeks to reveal the meaning and gain insight into the complexity of the situation by reflecting on one’s own preconceptions and the process of construction (of that insight). This approach emphasizes the (in-depth) relationship with the client, the construction process, and the existence of a multitude of truths (Glumbíková, 2019).

As a result of the above, social work students seem to apply their reflection through technical optics and subsequent self-regulation of emotions as a tool of how to deal with the demands of social work practice. This leads to suppression or emphasis of emotions and thus to experiences of inauthenticity, which can be exhausting for social workers in the long run.

From the resulting data, it therefore seems necessary to provide social work students with sufficient opportunities to work with holistically conceived reflexivity, which can be a tool for strengthening greater authenticity among social workers in their practice. (Future) social workers during their educational process should be provided with opportunities to gain an emotional experience from the social work practice in a safe environment as well as with tools for working with emotions such as reflective diaries (where students can record experiences from practice and further reflect on them), or both the group and individual reflections on practical experiences with mentors (e.g. using the critical incident analysis method) (similarly see e.g. Koole et al., 2012; Stanley & Bhuvaneswari, 2016). The authenticity of social work students can also be supported by the culture-setting in educational institutions. Of particular importance is the establishment of a blame-free organizational culture, which is characterized by establishment of a safe environment (an environment that does not raise concerns about mistakes and does not lead to shame), in which mistakes can be shared with colleagues and the mistakes themselves are perceived in the context of social work values as a space for learning (Sicora, 2017).

References

American Psychological Association (APA). (2010). Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct. http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/

Aukes, L. C. (2008). Personal reflection in medical education Groningen. University of Groningen.

Banks, S. (2012). Ethics and Values in Social Work. Palgrave Macmillan.

Barlow, C., & Hall, B. L. (2007). What about Feelings? A Study of Emotion and Tension in Social Work Field Education. Social Work Education, 26(4), 399 – 413.

Baumeiser, R. F., Vohs, K. D., & Tice, D. M. (2007). The Strength Model of Self-control. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 351 – 355.

Bono, J., & Vey, M. (2005). Towards Understanding Emotional Management at Work: A Quantitative Review of Emotional Labour Research. In C. E. Härtel & W. J. Zerbe (Eds.), Emotions in Organizational Behaviour (pp. 213 – 233). Erlbaum.

Boucher, H. C. (2011). The Dialectical Self-Concept II. Cross-role and within-role consistency, well-being, self-certainty, and authenticity. Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology, 42, 1251 – 1271.

Brotheridge, C. M., & Lee, R. T. (2002). Testing a Conservation of Resources Model of the Dynamics of Emotional Labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7(1), 57 – 67.

Cameron, L. D., & Jago, L. (2008). Emotion Regulation Interventions: A Common Sense Model Approach. British Journal of Health Psychology, 13(2), 215 – 221.

Catanzaro, S. J., & Mearns, J. (1990). Measuring generalized expectancies for negative mood regulation: Initial scale development and implications. Journal of Personality Assessment, 54, 546–563.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B. Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The Job Demands-resources Model of Burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 499 – 512.

Diefendorff, J. M., Richard, E. M. Yang, J. (2008). Linking Emotion Regulation Strategies to Affective Events and Negative Emotions at Work. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 73, 498 – 508.

Elliot, A. (2001). Concepts of the Self. UK Policy Press.

English, T., & John O. P. (2013). Understanding the Social Effect of Emotion Regulation: The Mediating Role of Authenticity for Individual Differences in Suppression. Emotions, 13(2), 314 – 329.

Erickson, R. J. (1994). Our Society, Our Selves: Becoming Authentic in an Inauthentic World. Advanced Development, 6, 27 – 39.

Forgas, J. P., Williams, K. D., & Laham, S. M. (2005). Social Motivation: Conscious and Unconscious Process. Cambridge University Press.

Gardner, F. (2016). Critical Spirituality in Holistic Practice. Journal for the Study of Spirituality, 6(2), 180-193.

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society and the Late Modern Age. Polity.

Glumbíková, K. (2019). The self of social workers in practice of field social work with families in the Czech Republic. Journal of Social Work Practice.

Goldman, B. M., & Kernis, M. H. (2002). Role of Authenticity in Healthy Psychological Functioning and Subjective Well-being. Annals of the American Psychotherapy: APA, 5, 18 – 20.

Grandey, A., Foo, S. C., Gorth, M., & Goodwin, R. E. (2012). Free to Be You and Me: A Climate of Authenticity Alleviates Burnout from Emotional Labour. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 17, 1 – 14.

Grant, L., Kinman, G., & Alexander, K. (2014). What´s All this Talk about Emotion? Developing Emotional Intelligence in Social Work Students. Social Work Education, 33(7), 874 – 889.

Henderson, A. (2001). Emotional Labour and Nursing: An Under-appreciated Aspect of Caring Work. Nursing Inquiry, 8, 130 – 138.

Ikenbuchi, J., & Rasmunssen, B. M. (2014). The Use of Emotions in Social Work Education. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 34(3), 285 – 301.

Johnson, A. (2007). Authenticity, Tourism and Self-Discovery in Thailand: Self-Creation and the Discrening Gaze of Trekkers and Old Hands. SOJOURN: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia, 22, 153 – 78.

Koole, S., Dorman, T., Aper, L., De Wever, B., Scherpbier, A., & Derese, A. (2012). Using Video-cases to Assess Student Reflection: Development and Validation of an Instrument. BMC Medical Education, 12(1), 12 – 22.

Lee R. T., Lovell, B. L., & Brotheridge, C. M. (2010). Tenderness and steadiness: Relating Job and Interpersonal Demands and Resources with Burnout and Physical Symptoms of Stress in Canadian Physicians. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40, 2319 – 2342.

Leary, M. R., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). The Nature and Function of Self-esteem: Sociometrical Theory, In M. P. Zanna (Ed.) Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 1 – 62). Academic Press.

Lewis, P. (2005). Suppression and Expression: An Exploration of Emotion Management in a Special Care Baby Unit. Work, Employment, and Society, 19, 565 – 581.

Litvack, A., Bogo, M., Mishna, F. (2010). Emotional Reactions of Students in Field Education: An Exploratory Study. Journal of Social Work Education, 46(2), 227 – 243.

Mann, S. (2005). A Health‐care Model of Emotional Labour. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 19(5), 304 – 317.

Ménard, J., & Brinet, L. (2011). Authenticity and Well-being in the Workplace: A Mediation Model. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 26, 331 – 346.

Navrátil, P. (Ed.). (2014). Reflexivní posouzení v sociální práci s rodinami [Reflective assessment in social work with families]. Masarykova univerzita.

O’Connor, P. (2006). Young People’s Constructions of the Self: Late Modern Elements and Gender Differences. Sociology, 40, 107 – 24.

Rogers, C. R. (1965). The Concept of Fully Functioning Persons. Pastoral Psychology, 16, 21 – 33.

Rupp, D. E., Spencer, S. (2006). When Customers Lash out: The Effects of Customer Interactional Injustice on Emotional Labour and the Mediating Role of Discrete Emotions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 971 – 978.

Schmidt, P. F. (2005). Authenticity and Alienation: Towards an Understanding of the Person beyond the Categories of Order and Disorder. In S. Joseph and R. Worsley (Eds.). Person-centred Psychopatology (pp. 75 – 90). PCCS.

Sicora, A. (2017). Reflective Practice and Learning from Mistakes in Social Work. Policy Press.

Sloan, M. (2007). The Real Self and Inauthenticity: The Importance of Self-Concept Anchorage for Emotional Experiences in the Workplace. Social Psychology Quarterly, 70, 305 – 18.

Smith, M. (2010). Sustaining Relationships: Working with Strong Feelings: Anger, Aggression and Hostility. In G. Ruch, D. Turnes, & A. Ward (Eds.), Relationship-based Social Work (pp. 102–117). Jessica Kingsley.

Stanley, S., & Bhuvaneswari, M. (2016). Reflective Ability, Empathy, and Emotional Intelligence in Undergraduate Social Work Students: A Cross-sectional Study from India. Social Work Education, 35(5), 560 – 575.

Toor, S., & Ofori G. (2009). Authenticity and its Influence on Psychological Well-being and Contingent Self-esteem of Leaders in Singapore Construction Sector. Construction Management and Economics, 27, 299 – 313.

Vannini, P., & Franzese, A. (2008). The Authenticity of Self: Conceptualization, Personal Experience, and Practice. Sociology Compass, 2/5, 1621 – 1637.

Van den Bosch, R., & Taris, T. W. (2014). Authenticity at Work: Development and Validation of an Individual Authenticity Measure at Work. Journal of Happiness Study, 15, 1 – 18.

Van Horn, Joan E., Taris,T. W., Schaufeli, W. B., & Schreurs, P. J. G. (2004). The structure of occupational well-being: a study among Dutch teachers. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77(3), 365 – 375.

Wood, A. M., Linley, P. A., Maltby, J., Baliousis, M., & Joseph, S. (2008). The Authentic Personality: A Theoretical and Empirical Conceptualization and the Development of the Authenticity Scale. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 55, 385 – 399.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

24 November 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-952-8

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

1

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-370

Subjects

Education, educational psychology, pedagogy, positive pedagogy, special education, second language teaching

Cite this article as:

Glumbíková, K., Mikulec, M., & Zegzulková, V. M. (2020). Authenticity, Reflexivity and Self-Regulation in Social Work Students: Implications for Education. In P. Besedová, N. Heinrichová, & J. Ondráková (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2020: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 1. European Proceedings of International Conference on Education and Educational Psychology (pp. 106-117). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epiceepsy.20111.10