Orphan’s Social Engagement and Demographic Relationship: A Preliminary Investigation From Pahang Orphanages

Abstract

Social engagement is essential to make sure that the orphans do not feel like they are being left behind by society. It is also necessary to support Sustainability Development Goal (SDG) in creating child well-being. Child well-being is both an indicator and a foundation of social and economic development. Therefore, this study aims to identify the social engagement of orphans in Pahang orphanages. Besides, this study examines the relationship and significant differences between demographic factors (gender, age, and years of living in orphanages) and social engagement among the orphans in Pahang orphanages. The questionnaire was distributed to 270 orphans aged 8 to 17 years old at 12 orphanages in Pahang, Malaysia. To test research objectives, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) was used in generating the descriptive result, regression and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). The result shows that the overall social engagement in Pahang orphanages is considered moderately high. Besides, the result revealed that gender and years of living in orphanages have an impact on social engagement. For these results, there is a need for the policymakers to organize more programs between orphans and society by considering the gender and years of living in orphanages to support the National Children’s Mental and Well-being Strategy.

Keywords: Demographic, social engagement, orphans, orphanages, SPSS

Introduction

Orphans and underprivileged care of children have remained a serious issue in society. At least 140 million children had lost at least one or both parents as reported by United Nations Children’s Fund (2019). As they are orphans, some of them choose to stay in childcare due to lack of support they received from their loved one (Suryaningsih et al., 2022). In the Malaysian context, at least 64,000 children were estimated to be living in childcare institutions for the year 2021 (Hazariah et al., 2020). From that, 87% of the children still have at least one living parent. The number is expected to increase since some childcare institutions are still unregistered under government or private orphanages.

Alfred et al. (2018) revealed that low levels of guardian involvement among orphans at the orphanages. This issue led to difficulty to have a sense of belonging and acceptance among orphans’ families before they start feeling it among their social groups. Therefore, the responsibility to care for children in childcare is not only for the guardian only. The society also needs to engage and support the children for their overall holistic development (Mir & Bhat, 2022). Society needs to provide social engagement as the social interactions with them create self-belonging and form social bonds (Thurman et al., 2008). The caregivers, friends and management at the orphanage, teachers and the public as the target group for the social engagement should avoid negative attitudes and enhance care and protection towards children from the institution (Muguwe et al., 2011).

Suryaningsih et al. (2022) revealed that children could get social support in the form of comfort, care, or help from other people in the orphanage surroundings. Physical activities include recreational activities and innovations that can strengthen bonds between orphanage residents and society. Besides, society can offer continuous support and serve as role models to inspire the orphans for future directions. Sadly, these orphans still lack the nurturing which required the stimulation on environment. Therefore, the objectives of this study are:

- To identify the level of social engagement of orphans in Pahang orphanages.

- To explore the relationship between demographic (gender, age, and years of living in orphanages) with social engagement in Pahang orphanages.

- To examine the significant difference between demographic (gender, age, and years of living in orphanages) with social engagement in Pahang orphanages.

Limited studies focus on social engagement in orphanages in which previous studies highly emphasize the psychosocial well-being of orphans (Nortje & Pillay, 2022; Ringson, 2022; Yimer, 2022). Orphans who stay at Pahang orphanages were selected for this study since varies challenges in orphan management faced by caregivers and management and the increasing number of orphans every year Department of Social Welfare Malaysia (2022). Besides, this study can strengthen better life of orphans with the strong community ties. Furthermore, this study contributes to the literatures on whether demographic factors affect social engagement among orphans in Pahang orphanages. It is important to have high social engagement by focusing on the specific demographic, including gender, age, and years of living in orphanages, in order to empower their well-being.

Literature Reviews

Social engagement refers to the ability to initiate social interaction and be receptive to social overtures from others (Tsuchiya‐Ito et al., 2022). The level of social engagement is considered as one of the most important predictor of children’s successful learning outcomes include for orphans who live at orphanages (Sjöman et al., 2021). This engagement will create a positive vibe, self-belonging, and attachment, which will create better psychological well-being. It will avoid negative aspects such as social isolation from the community, anxiety, and depression. In addition, this engagement will be working collaboratively with the community to improve the well-being of the orphans (Johnston, 2018). There are many factors that influence the community care provided to orphans, including social, historical, and cultural factors (Thurman et al., 2008). Besides, a demographic factor can also influence social engagement, as mentioned by Huxhold and Fiori (2019) and Sillaots et al. (2020).

Demographic factor on gender is capable of influencing social engagement. Thomas (2011) explained the difference in social engagement levels between women and men. The women show greater social engagement with lower levels of subsequent physical and cognitive limitations. Meanwhile, men are more on a lower level of social engagement, but they have greater physical and cognitive limitations. Ejechi (2015) added that women engage more with society in religious activities and visitations and participate in the formal volunteer work, while men prefer to have informal socialization with a family and friends. However, development in technology helps all the gender to maintain their preferred type of social engagement (Kim et al., 2017). In terms of the children, Sjöman et al. (2021) explained that boys with high levels of hyperactivity will show lower social engagement except if they receive enough special support to improve their attention and perseverance in everyday activities. Therefore, it leads to the following hypothesis:

H1a: There is a significant relationship between genders and the social engagement of orphans in Pahang orphanages.

H1b: There is a significant difference in the social engagement between genders of orphans in Pahang orphanages.

Age will also affect social engagement. Age has positive influences on social engagement since they will have different abilities in physical activity (Pan, 2009). Hofer and Hargittai (2021) revealed that older individuals tend to have a more online social engagement, which will increase their anxiety due to negative feedback from others. Besides, older people have more social engagement since they can crystallize cognitive age-adjusted abilities (Borgeest et al., 2020). Besides, children often show a low level of social engagement with peers and adults if they have Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) (Kellems et al., 2022). Therefore, it leads to the following hypothesis:

H2a: There is a significant relationship between age and the social engagement of orphans in Pahang orphanages.

H2b: There is a significant difference in social engagement between the age of orphans in Pahang orphanages.

Kiely and Flacker (2003) explained that the duration that the children stay at the orphanages would affect their social engagement with the people surrounding them. Lapane et al. (2022) and Ahmad (2021) mentioned that individuals who live in special care and with other people might increase the odds of high social connectedness and improve their mental health. The evidence is also supported by Shiferaw et al. (2018), who found that individual in orphanages for less than 2 years has a possibility of depression of 2.08 times higher compared with those who were in orphanages for more than 2 years. However, Rolandi et al. (2020) explained the need to avoid self-isolation in the same place for a long duration since it will affect older adults’ psychological and social well-being. Therefore, it leads to the following hypothesis:

H3a: There is a significant relationship between years of living in orphanages and the social engagement of orphans in Pahang orphanages.

H3b: There is a significant difference in the social engagement between years of living in orphanages of orphans in Pahang orphanages.

Theoretical framework

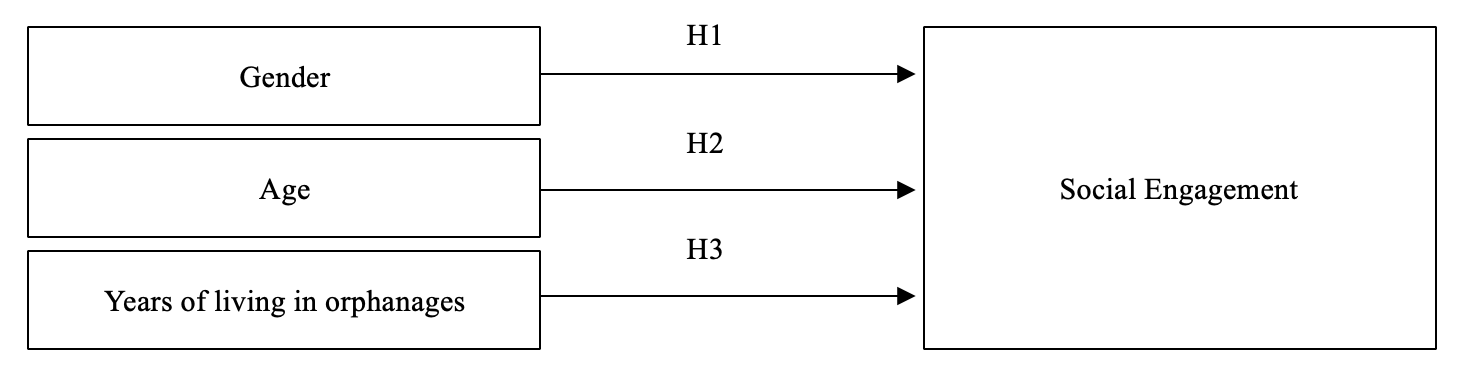

Social capital theory refers to the social relationships that facilitate certain actions of individuals and accumulate human capital (Bankston, 2022). This social capital can enable the individual to set the relationship with others, including friends, colleagues, and more general contacts. It also facilitates coordinating actions more effectively (Crosby et al., 2009). Besides, Kim and Cannella (2008) also studied that social capital will create trust, norms, and networks, which create either internal social capital or external social capital. In this study, the orphans will have internal social capital with other people in the orphanages, for example, caregivers and friends as shown in Figure 1. While external social capital ties and relations with various outside include nongovernment agencies and people surrounding orphanages.

Methodology

Research methodology

The sample used for this study is 270 orphans at the age of 7 years old and above who live at 12 Pahang orphanages. The respondents must receive basic education from the school to ensure they are able to understand the language used in the questionnaire. Besides, Pahang orphanages were selected since it is reported to have the highest number of childcares under the Department of Social Welfare Malaysia (2022).

For data collection, a questionnaire survey was used and distributed face-to-face for two months, from November to December 2021. The questionnaire consists of two-part which are demographic items for Part A, and social engagement for part B. Part A comprise of three questions on gender, age and years of living in orphanages. Part B consists of social engagement aspects which were measured using the five-Likert type with 1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Moderate Disagree, 4= Agree, and 5 = Strongly Agree. The questions on social engagement related to the engagement of orphans with people inside and outside the orphanages which was developed based on research conducted by Tsuchiya‐Ito et al. (2022), Ahmad and Jamil (2021), Tuovinen et al. (2020), and Fredricks et al. (2016). The interpretation of the levels of social engagement are translated into four level as depicted in Table 1 based on Ahmad et al. (2018).

Analytical methods

This study uses SPSS version 25 to generate descriptive result, regression, and ANOVA. The descriptive result was used to identify the social engagement of orphans in Pahang orphanages. A regression analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between the variables (Uyanık & Güler, 2013). In this study, regression was used to measure the relationship between demographic factors and social engagement. According to Abdul-Wahab et al. (2005), ANOVA is used to compare two means from two groups. This ANOVA will determine the influence that independent variables have on the dependent variable in a regression study. For this study, ANOVA will be used to measure the significant difference between demographic factors with social engagement.

Results

Respondents’ demographic data

Out of 270 respondents, 122 (45.19%) are male orphans, and 148 are female orphans (54.81%). In terms of age, 160 (59.26%) respondents are in the range of 13-17 years old, which means they are in secondary school and the remaining 110 (40.74%) at 8-12 years old. The majority (140, 51.9%) respondents already live in the same orphanages for 2 years, and only 3 (1.1%) respondents live there for 10 years. Table 2 shows the demographic information of the respondents.

Social engagement

Table 3 presents the results regarding social engagement of orphans in Pahang orphanages. To describe the strength of each statement, the mean score for each item was used which means 1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Moderate Disagree, 4= Agree, and 5 = Strongly Agree. The highest mean score was recorded for the statement “I always get involved in activities organized by outsiders” (M=4.074). The second highest mean score was recorded for the statement “I was always treated well” (M=3.80), followed by the statement “I feel loved by others” (M=3.80) and “other people are always helpful if I need help” (M=3.70). The statement “I am confident to deal with outsiders” (M=3.30) was recorded as the lowest mean score. Overall, the mean for social engagement is rated as moderately-high according to the rate by Ahmad et al. (2018).

Based on the results obtained in Table 3, the results show that the respondents strongly agree (45.56%) that they are always involved with activities organized by outsiders, for example, non-profit organizations, universities/colleges, and companies. Trampa and Venetsanou (2022) revealed that physical activity organized at the orphanages has positive implications for the quality of life of youth. World Health Organization (WHO, 2019) explained that quality of life is important for individual and public health to support the well-being of people. Hyndman et al. (2017) support that physical activity, either free or organized, offers a holistic framework for social-psychological-physical development.

Additionally, the respondent exhibited that they strongly agree (31.85%) that they feel loved by people. The respondents have received adequate encouragement and care from their social environment to further inspire them for daily activities. Gatsi (2014) explained that the child needs consistent love and care from the main support system. The main support system is from organizations, including schools and orphanages, since they are sensitive to their loss of parents, financial problems, and family problems.

The result also identified that 7.78% of respondents strongly disagree that they are confident in dealing with outsiders. Burnett (2021) mentioned that the experience of social rejection due to their destitution, poor living conditions, and appearance affects lower interpersonal contacts. Besides, it will create difficulties in cultivating possible relationships with other parties. Besides, caregiving also has the responsibility to develop the psychological development of children, including cognitive abilities, language, attachment, and emotional maturity, as well as behavioral issues (Khalid et al., 2022). Therefore, the result for first research objective proved that overall social engagement among orphans in Pahang orphanages is moderately highly but still need continuous social support and social participation from caregiver, NGO, regulators and public.

For second research objective, regression analysis is performed to identify the relationship between demographic factors and social engagement. Table 4 indicates that gender and duration of stay in the orphanages are significant, with social engagement at a p-value less than 0.005. Therefore, H1a and H3a are accepted. In addition, age and duration of stay in the orphanages are insignificant to social engagement. Hence, H2a is rejected.

For third research objective, further analysis was done to examine the significant difference in demographic (gender, age, and years of living in orphanages) with social engagement using ANOVA. The result in Table 5 shows that there is a statistically significant difference at p<0.05 level in social engagement based on gender and duration of stay in the orphanages. Therefore, H1b and H3b are accepted. Meanwhile, the result provides evidence that no significant difference was found between age and social engagement. It means that age does not influence social engagement among orphans in Pahang orphanages. Therefore, H2b is rejected.

The result on gender supports previous studies by Feng et al. (2014), where they found female individuals have more varied social engagement compared to male individuals since female individuals encounter a greater level of communication apprehension. Besides, the female individual who is more interested in engaging with her friends had a lower cognitive decline. Lee and Yeung (2019) reported that social engagement would be declined among female individuals who have lower education. Male individuals do not have an interest in engaging in non-paid socially productive activities such as volunteering and caregiving (Thomas, 2011).

In terms of years of living in orphanages, the result found is consistent with Kiely and Flacker (2003). They revealed that a longer duration of survival in the same place would increase the level of social interaction due to familiarity among members. Yi and Kim (2022) also supported that the long-term care received will influence social engagement, which will improve the quality of life among the residents of institutions.

For age, the result is not significant with social engagement. Meek et al. (2018) pointed out that health status, including disease-related emotional/physical problems, regardless of age, might influence engagement with society. Besides, Ihm (2018) supported that the addiction to smartphones among children will lead to less participation in social engagement. Csibi et al. (2021) commented that excessive use of smartphone use is among adolescents aged 12 to 18 years.

Conclusion

For first research objective, the overall social engagement in orphanages is considered moderately high based on the moderate mean scores recorded for all the statements from the questionnaires. The highest mean score is on the statement that they always get involved in activities organized by an outsider. At the same time, the lowest mean scores were recorded for the statement that the respondents are confident in dealing with outsiders, which reflects the effectiveness of physical activities organized inside or outside the orphanages. For second and third research objectives, the finding of this study also highlights that gender and years of living in orphanages have an influence on social engagement. Besides, gender and years of living in orphanages have significant differences in social engagement. This result is aligned with the social capital theory that emphasizes that one of the factors affecting social engagement is related to the actor and the nature of the relationship between any two actors, which will relate to familiarity and trust (Koley et al., 2020).

This study recommends that the policymaker needs to have a proper guideline for orphanages to monitor the level of social engagement among orphans. It is to ensure that Malaysia can support Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 10, in creating a more equitable, just, and sustainable world for all. Besides, this study provides more information on the demographic factor that need to consider to ensure active engagement throughout the physical and virtual activities in the orphanages. More importantly, this study successfully fills the gaps due to limited studies done on social engagement for orphans in orphanages. Therefore, future research should focus on the effectiveness of physical activities for the orphans according to their gender and years of living in orphanages in order to improve their quality of life, including enhancing self-confidence and improving self-esteem.

Since this study only covers one state in Malaysia, generalization cannot be drawn. However, this preliminary idea of how the orphans feel about social engagements can be imagined in brief. To generalize the result, more respondents are needed, and more data must be collected, including interviews with caregivers, orphans, and society.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the YCU grant (Project No. 202210046YCU) provided by Yayasan Canselor UNITEN (YCU).

References

Abdul-Wahab, S. A., Bakheit, C. S., & Al-Alawi, S. M. (2005). Principal component and multipleregression analysis in modelling of ground-level ozone and factors affecting its concentrations. Environmental Modelling & Software, 20(10), 1263- 1271. DOI:

Ahmad, J., Ahmad, A. R., Malek, J. A., & Ahmad, N. A. I. L. (2018). Social Support and Social Participation among Urban Community in Malaysia. International Journal of Academic Research Business and Social Science, 8, 418-428. DOI:

Ahmad, N. N. (2021). Identification of the Elements of Social Well-being Index for Orphans and Vulnerable Adolescents through Principal Component Analysis (PCA). Global Business & Management Research, 13.

Ahmad, N. N., & Jamil, N. N. (2021). Quality of Education Provision for Orphans and Vulnerable Adolescents in The Time of Covid-19 at Orphanages. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 11(8), 605–611. DOI:

Alfred, A. J., Ma’rof, A. M., & Buang, N. (2018). The Relationship Between Institutional Environment, Guardian Involvement, Academic Achievement and Learning Motivation of Children Reared In a Malaysian Orphanage. Jurnal VARIDIKA, 29(2), 147-157. DOI:

Bankston III, C. (2022). Applications of social capital theory. In Rethinking Social Capital (pp. 85-85). DOI:

Borgeest, G. S., Henson, R. N., Shafto, M., Samu, D., Cam-CAN, & Kievit, R. A. (2020). Greater lifestyle engagement is associated with better age-adjusted cognitive abilities. Plos one, 15(5), e0230077. DOI:

Burnett, C. (2021). Framing a 21st century case for the social value of sport in South Africa. Sport in Society, 24(3), 340-355. DOI:

Crosby, R. A., Kegler, M. C., & DiClemente, R. J. (2009). Theory in health promotion practice and research. Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research, 2, 3-17.

Csibi, S., Griffiths, M. D., Demetrovics, Z., & Szabo, A. (2021). Analysis of problematic smartphone use across different age groups within the ‘components model of addiction’. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 19(3), 616-631. DOI:

Department of Social Welfare. (2022, June 2021). Full List of Care Centers. Social Welfare Department Malaysia.https://www.jkm.gov.my/jkm/index.php?r=portal/carecenter&map_type=02&inst_cat=&id=dW5XdUJqMjE0bnUrVVg3QXl3QjFodz09&Map%5Bname%5D=&Map%5Binst_cat%5D=&Map%5Bstate%5D=Pahang&Map%5B%20district%5D=

Ejechi, E. O. (2015). Gender differences in the social engagement and self-rated health of retirees in a Nigerian setting. IOSR-JHSS, 20(4), 26-36.

Feng, L., Ng, X. T., Yap, P., Li, J., Lee, T. S., Håkansson, K., & Ng, T. P. (2014). Marital status and cognitive impairment among community-dwelling Chinese older adults: the role of gender and social engagement. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders extra, 4(3), 375-384. DOI:

Fredricks, J. A., te Wang, M., Schall Linn, J., Hofkens, T. L., Sung, H., Parr, A., & Allerton, J. (2016). Using qualitative methods to develop a survey measure of math and science engagement. Learning and Instruction, 43, 5–15. DOI:

Gatsi, R. (2014). Analysis of The Impact of Existing Intervention Programmes On Psychosocial Needs: Teenage Orphans’ perceptions. Academic Research International, 5(1), 180.

Hazariah, A. H. S., Fallon, D., & Callery, P. (2020). An Overview of Adolescents Sexual and Reproductive Health Services Provision in Malaysia. Comprehensive Child and Adolescent Nursing, 19, 1–7. DOI:

Hofer, M., & Hargittai, E. (2021). Online social engagement, depression, and anxiety among older adults. New Media & Society, 0(0). DOI:

Huxhold, O., & Fiori, K. L. (2019). Do demographic changes jeopardize social integration among aging adults living in rural regions? The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 74(6), 954-963. DOI:

Hyndman, B., Mahony, L., Te Ava, A., Smith, S., & Nutton, G. (2017). Complementing the Australian primary school Health and Physical Education (HPE) curriculum: exploring children's HPE learning experiences within varying school ground equipment contexts. Education 3-13, 45(5), 613-628. DOI:

Ihm, J. (2018). Social implications of children’s smartphone addiction: The role of support networks and social engagement. Journal of behavioral addictions, 7(2), 473-481. DOI:

Johnston, K. A. (2018). Toward a theory of social engagement. The handbook of communication engagement, 1, 19-32. DOI:

Kellems, R. O., Charlton, C. T., Black, B., Bussey, H., Ferguson, R., Gonçalves, B. F., & Vallejo, S. (2022). Social Engagement of Elementary-Aged Children With Autism Live Animation Avatar Versus Human Interaction. Journal of Special Education Technology, 0(0). DOI:

Khalid, A., Morawska, A., & Turner, K. M. (2022). Pakistani orphanage caregivers' perspectives regarding their caregiving abilities, personal and orphan children's psychological wellbeing. Child: Care, Health and Development, 49(1), 145– 155. DOI:

Kiely, D. K., & Flacker, J. M. (2003). The protective effect of social engagement on 1-year mortality in a long-stay nursing home population. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 56(5), 472-478. DOI:

Kim, J., Lee, H. Y., Christensen, M. C., & Merighi, J. R. (2017). Technology access and use, and their associations with social engagement among older adults: Do women and men differ? Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72(5), 836-845. DOI:

Kim, Y., & Cannella Jr, A. A. (2008). Toward a social capital theory of director selection. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 16(4), 282-293. DOI:

Koley, G., Deshmukh, J., & Srinivasa, S. (2020, October). Social Capital as Engagement and Belief Revision. In International Conference on Social Informatics (pp. 137-151). Springer, Cham. DOI:

Lapane, K. L., Dubé, C. E., Jesdale, B. M., & Bova, C. (2022). Social Connectedness among Long-Stay Nursing Home Residents with Alzheimer’s and Dementia: Exploring Individual and Facility-Level Variation. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord, 51(3), 249–261. DOI:

Lee, Y., & Yeung, W. J. J. (2019). Gender matters: productive social engagement and the subsequent cognitive changes among older adults. Social Science & Medicine, 229, 87-95. DOI:

Meek, K. P., Bergeron, C. D., Towne Jr, S. D., Ahn, S., Ory, M. G., & Smith, M. L. (2018). Restricted social engagement among adults living with chronic conditions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(1), 158. DOI:

Mir, B., & Bhat, M. (2022). Impact of Personality Disposition, Study Habits and Mental Health on Academic Achievement of Orphan Students: Comparative Analysis. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 6(3), 6792-6800.

Muguwe, E., Taruvinga, F. C., Manyumwa, E., & Shoko, N. (2011). Re-integration of institutionalised children into society: A case study of Zimbabwe. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 13(8), 142-149.

Nortje, A. L., & Pillay, J. (2022). Vulnerable young adults’ retrospective perceptions of school-based psychosocial support. South African Journal of Education, 42(1), 1-9. DOI:

Pan, C. Y. (2009). Age, social engagement, and physical activity in children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3(1), 22-31. DOI:

Ringson, J. (2022). The Caregivers’ Perspective in Coping with the Challenges Faced by Orphans and Vulnerable Children at the Household Level in Zimbabwe. In Parenting-Challenges of Child Rearing in a Changing Society. IntechOpen. DOI:

Rolandi, E., Vaccaro, R., Abbondanza, S., Casanova, G., Pettinato, L., Colombo, M., & Guaita, A. (2020). Loneliness and social engagement in older adults based in Lombardy during the COVID-19 lockdown: The long-term effects of a course on social networking sites use. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(21), 7912. DOI:

Shiferaw, G., Bacha, L., & Tsegaye, D. (2018). Prevalence of depression and its associated factors among orphan children in orphanages in Ilu Abba Bor Zone, South West Ethiopia. Psychiatry journal, 2018. DOI:

Sillaots, M., Jesmin, T., Fiadotau, M., & Khulbe, M. (2020, September). Gamifying Classroom Presentations: Evaluating the Effects on Engagement Across Demographic Factors. In European Conference on Games Based Learning (pp. 537-XIX). Academic Conferences International Limited.

Sjöman, M., Granlund, M., Axelsson, A. K., Almqvist, L., & Danielsson, H. (2021). Social interaction and gender as factors affecting the trajectories of children’s engagement and hyperactive behaviour in preschool. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(2), 617-637. DOI:

Suryaningsih, C., Hani Putri Utami, I., & Imelisa, R. (2022). Coping Strategies of Adolescents in Orphanages. KnE Medicine, 2(2), 161–178. DOI:

Thomas, P. A. (2011). Gender, social engagement, and limitations in late life. Social science & medicine, 73(9), 1428-1435. DOI:

Thurman, T. R., Snider, L. A., Boris, N. W., Kalisa, E., Nyirazinyoye, L., & Brown, L. (2008). Barriers to the community support of orphans and vulnerable youth in Rwanda. Social Science & Medicine, 66(7), 1557-1567. DOI:

Trampa, K., & Venetsanou, F. (2022). Can A Physical Activity Programme Improve The Quality Of Life In Youth Who Live In An Orphanage? A Mixed Methods Study. Facta Universitatis Series: Physical Education And Sport, 20(1), 73-87. DOI: 10.22190/FUPES220225007T

Tsuchiya‐Ito, R., Naruse, T., Ishibashi, T., & Ikegami, N. (2022). The revised index for social engagement (RISE) in long‐term care facilities: reliability and validity in Japan. Psychogeriatrics, 22(1), 122- 131. DOI:

Tuovinen, S., Tang, X., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2020). Introversion and social engagement: scale validation, their interaction, and positive association with self-esteem. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 590748. DOI:

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The state of the world’s children 2019: A fair chance for every child. https://www.unicef.org/reports/state-worlds-children-2016

Uyanık, G. K., & Güler, N. (2013). A study on multiple linear regression analysis. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 106, 234-240. DOI:

World Health Organization. (WHO, 2019). Coming of Age: Adolescent health. WHO health international. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/coming-of-age-adolescent-health

Yi, J. Y., & Kim, H. (2022). Factors associated with low and high social engagement among older nursing home residents in Korea. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 23(7), 1185-1190. DOI:

Yimer, B. L. (2022). Psychosocial well-being of child orphans: The influence of current living place. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 32(3), 282-287. DOI:

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

18 August 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-963-4

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

1

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1050

Subjects

Multi-disciplinary, Accounting, Finance, Economics, Business Management, Marketing, Entrepreneurship, Social Studies

Cite this article as:

Ahmad, N. N. (2023). Orphan’s Social Engagement and Demographic Relationship: A Preliminary Investigation From Pahang Orphanages. In A. H. Jaaffar, S. Buniamin, N. R. A. Rahman, N. S. Othman, N. Mohammad, S. Kasavan, N. E. A. B. Mohamad, Z. M. Saad, F. A. Ghani, & N. I. N. Redzuan (Eds.), Accelerating Transformation towards Sustainable and Resilient Business: Lessons Learned from the COVID-19 Crisis, vol 1. European Proceedings of Finance and Economics (pp. 778-789). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epfe.23081.70