Abstract

A sukuk can generally be understood as an investment document or certificate that proves the existence of right for certificate holder to an underlying profit, project or asset. However, there are some obstacles in structuring ‘asset-backed’ sukuk from a shariah aspect such as the difficulty of changing the name in the underlying asset grant from obligor to sukuk holder, tax issues and implications to ‘negative pledge’. This study uses a qualitative approach in which the analysis of the original book of fiqh and a review of past studies by applying the method of content analysis. Content analysis has been defined as a systematic, replicable technique for compressing many words of text into fewer content categories based on explicit rules of coding. The most common notion about the content analysis is simply means doing a word- frequency count. The assumption made is that the words that are mentioned most often are the words that reflect the greatest concerns. Thus, this study will use the words counting codes from the past literatures to examine the shariah issues that are hurdles to the industry in determining the nature of underlying asset for the sukuk marketability so that the liquidity problems may be resolved.

Introduction

The Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) (2007) has defined sukuk as:

Certificates of equal value representing undivided shares in ownership of tangible assets, usufruct and services or (in the ownership of) the assets of particular projects or special investment activity, however, this is true after receipt of the value of the sukuk, the closing of subscription and the employment of funds received for the purpose for which the sukuk were issued. (p. 85)

Based on the definition of AAOIFI, the sukuk structuring process is based on the underlying asset. It is a document that proves the existence of rights either to an asset, service or any benefit from the asset depending on the type of contract and its structuring process. Thus, securities issued by making solely a group of debts or receivables as the underlying assets are not included in the sukuk category.

Meanwhile, the Securities Commission (SC) defines sukuk with a broader definition (Ahmad, 2020) as they say the certificates of equal value evidencing undivided ownership or investment in the assets using Shariah principles and concepts endorsed by the Shariah Advisory Council (SAC). By this definition, sukuk is not only limited in its meaning by referring to equity -based financial instruments but can also refer to debt -based financial instruments. This means that instruments issued on the basis of receivables are also categorized as sukuk. Sukuk is seen to have very similar goals and roles to conventional bonds (Etudaiye-Muhtar, 2016) (From the perspective of the issuer (the entity that issues the sukuk), the sukuk plays a role in obtaining funds or financing from investors for the purpose of project development, business expansion or any commercial purpose.

Meanwhile, from the investor's perspective, sukuk is a medium to channel funds or offer financing that has the potential to provide a profit return. The sukuk market is seen to be able to help boost economic growth (Yıldırım et al., 2020). However, shariah scholars have differed on the marketability of some types of sukuk in the secondary market. Shariah supervisory bodies such as AAOIFI and the SAC of the Securities Commission have issued different resolutions from each other on sukuk trading activities in the secondary market. This arises as a result of differences of opinion from the perspective of fiqh, especially on the nature or character of al-maliyah (property nature) of sukuk whether it can be considered as a separate property or by looking at the type of underlying asset. These differences also have an impact on the liquidity of sukuk as well as the construction of an active secondary market for sukuk.

Sukuk historical background

Interestingly, sukuk as a financial instrument is not a creation of the modern financial industry but the concept was introduced a long time ago, in the first century of Hijrah. During the time of Caliph Marwan in the Umayyad Dynasty, he paid his army's salary in cash or cash-substitute instruments. The cash substitute instrument was then known as sukuk today. Sukuk used at that time is also known as commodity coupon or grain coupon. These coupons are used to redeem grains such as wheat when they have reached their maturity date. However, its use has been stopped due to the criticism of Islamic scholars at that time. However, 12 centuries later during the Ottoman Empire, financial certificate instruments were introduced to finance the government's finances through debt. The certificate is known as esham, iltizam and malikane which all refer to income tax security certificates. Esham appears to have neither tangible nor intangible assets except the right to collect taxes. This situation does not meet the standard of accepting sukuk at the global level. However, this esham structure seems to be in line with the definition given by the Shariah Committee in Malaysia. This esham structuring system was introduced in 1775 during the ottoman empire to finance their budget deficit due to heavy spending on the war against Russia including paying compensation to Russia for their defeat (Muhammad et al., 2015).

Jordan and Pakistan effort on developing sukuk

One of the earliest efforts in developing a shariah-compliant security certificate was in Jordan in 1978. This can be seen when the Jordanian government at the time allowed the Jordan Islamic Bank to issue bonds known as muqaradah bonds which were finally gazetted through the Muqaradah Bond Act 1981. Simultaneously with that, Pakistan also made several improvements to its legal framework in June 1980 to enable the issuance of interest-free corporate finance certificates. This certificate is very similar in concept to equity-based sukuk to allow investors to share the profits from the funders' investments. The string, the Government of Pakistan has approved rules and ordinances related to Mudarabah and companies 1981. However, this effort did not bring significant results due to lack of preparation from an infrastructure point of view and lack of transparency from an implementation point of view (Iqbal & Mirakhor, 2011)

Malaysia and Turkey's revival attempt in sukuk development

The Malaysian government introduced the Government Investment Issue (GII) in 1983, while the Turkish government introduced the Gelir Ortakligi Senetleri (GOS) in 1984. However, the development and experience experienced by these two countries differed when the bonds introduced by the Turkish government did not last long. due to the volatile exchange of political power. On the other hand, the Malaysian government continues this good effort to the level of the fastest development in the world. Aided by a wide network of financial institutions, as well as an efficient regulatory and supervisory system, Malaysia is the most successful country in the development of the sukuk market.

However, the sukuk market was not as active as expected until 2001 when the sukuk market began to become an alternative to the conventional bond market. For example, Bahrain has issued their first ijarah sukuk in the domestic market with an amount of USD250 million. Sukuk with a maturity of 6 months has become a stepping stone to the birth of sukuk in the Islamic financial market where Islamic equity and debt- based instruments have begun to be traded. in the same year, the Islamic Religious Council of Singapore (MUIS) issued SGD 25 million worth of sukuk through the musharakah principle of sukuk maturing within 5 years. Similarly, Kumpulan Guthrie Berhad, a Malaysian-owned corporate company that also successfully issued their first corporate sukuk, also in 2001 (Muhammad et al., 2015).

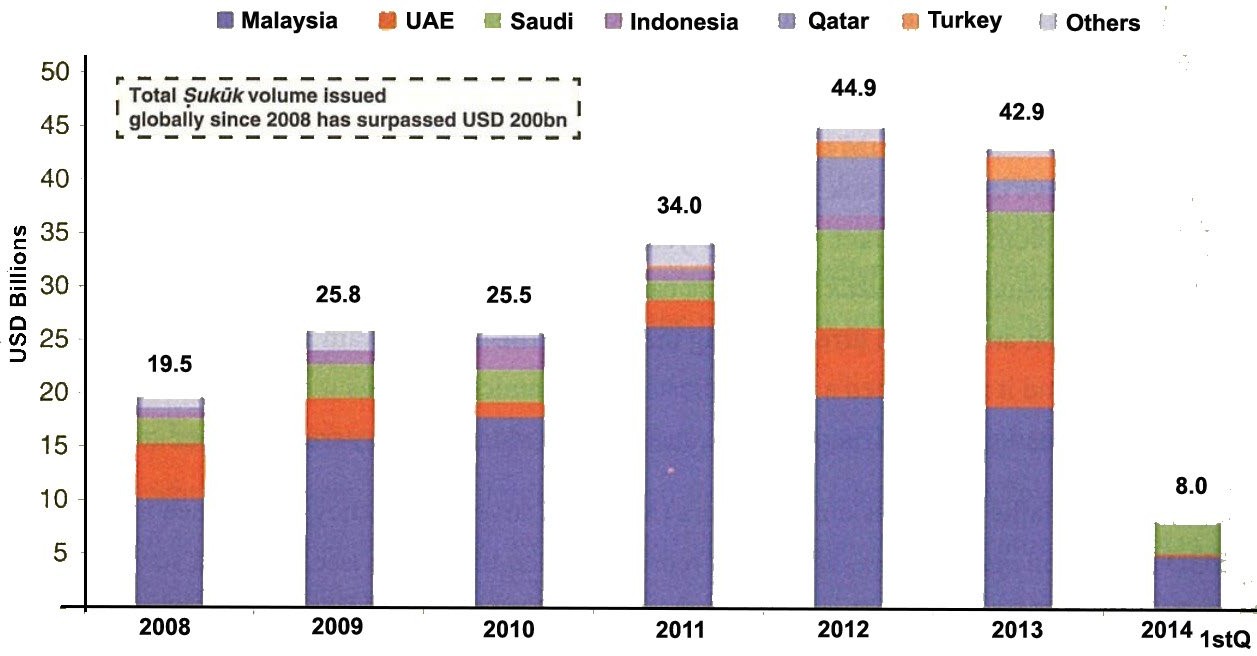

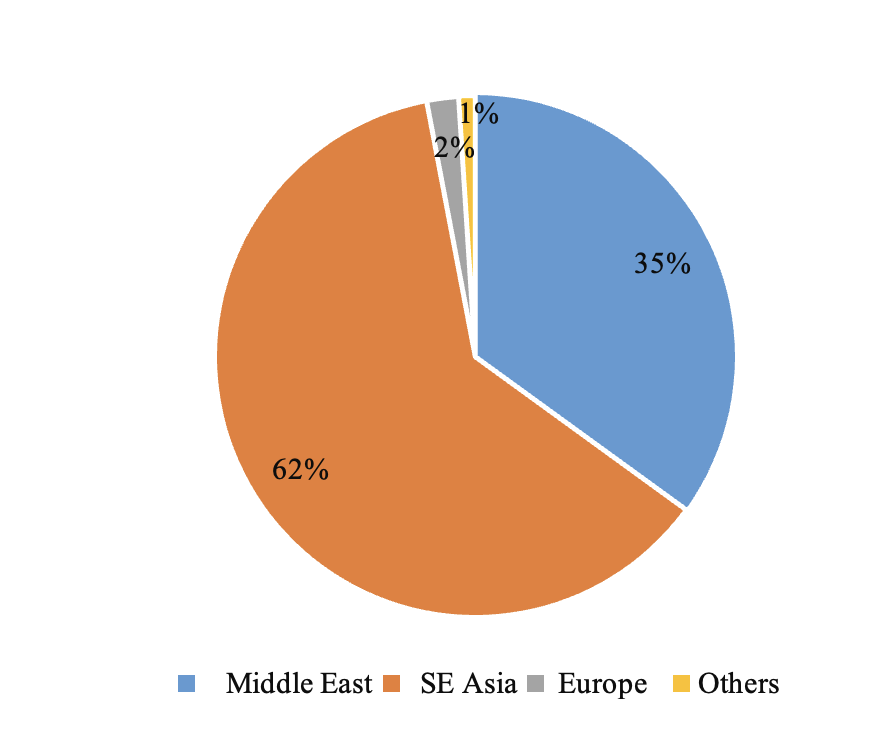

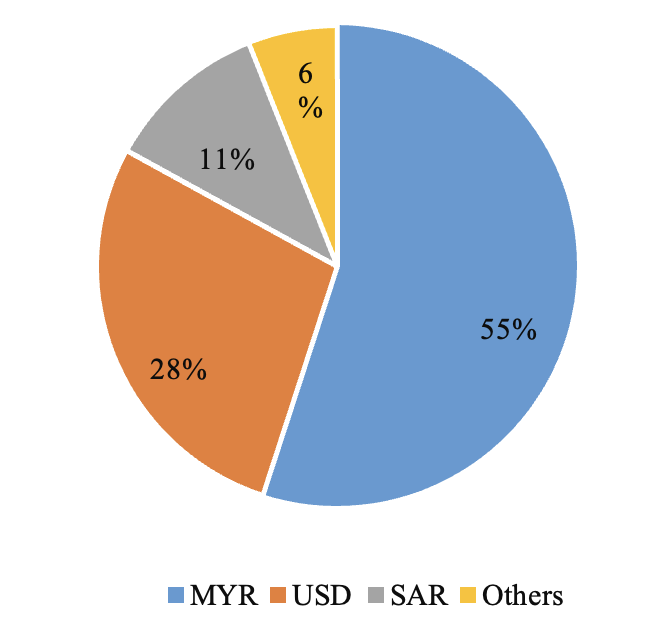

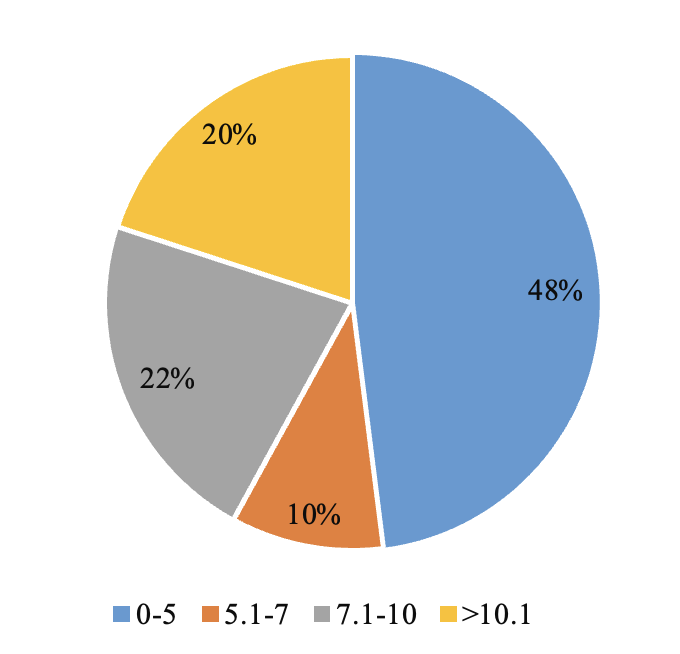

As shown in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, it was found that there was significant growth between 2008 and 2013 despite the global financial crisis at that time. In 2010, global issuance of sukuk reached a total of USD25 trillion and since then, the sukuk market has recorded a growth rate of 33% and 32% with a trading volume of USD34.01 billion and USD44.88 billion in 2011 and 2012. On average, sukuk issuance at the global level has grown at a rate of 18% per year for a period of 5 years (2009-2013). The average value of sukuk issuance in 2013 has reached almost USD 43 billion with a slightly lower dilution rate compared to the previous year. This is likely a cautious and wait-and-see attitude by investors in the Islamic financial market. In 2014, the expected supply of new sukuk will continue to grow at the same rate as in previous years. With the participation of countries such as Oman and Morocco that have further streamlined their legal systems and Islamic financial regulations, the amount of sukuk issuance from the Middle East market is expected to account for half of global sukuk issuance.

In the Islamic capital market, sukuk instruments can be divided into the following divisions:

Asset-Based Sukuk

Most of the sukuk that are traded today are of this type, whether they are structured as ijarah, wakalah, salam, istithmar, murabaha or others. This sukuk is traded through fixed income capital

Subordinate Sukuk

This type of sukuk is usually structured on the principles of ijarah, wakalah, mudharabah and musyarakah. Usually, a subordination structure is required by certain issuers who are looking to meet certain capital or debt ratio requirements. In a subordinated sukuk, the sukuk holders will have legal recourse only to the issuer but subordinate to all senior creditors.

Secured Sukuk and Asset-Backed Sukuk

Sukuk issuers usually choose this type if they need off-balance-sheet financing and they do not obtain a good credit rating without providing returns to sukuk holders. The difference between asset-based sukuk and asset-backed sukuk is the guarantee given by the sukuk issuer in asset-based sukuk, while asset-backed sukuk is guaranteed by assets owned by the sukuk issuer.

In discussing the sukuk structure, there are several principles used as the basis of sukuk issuance, among them:

BBA Sukuk

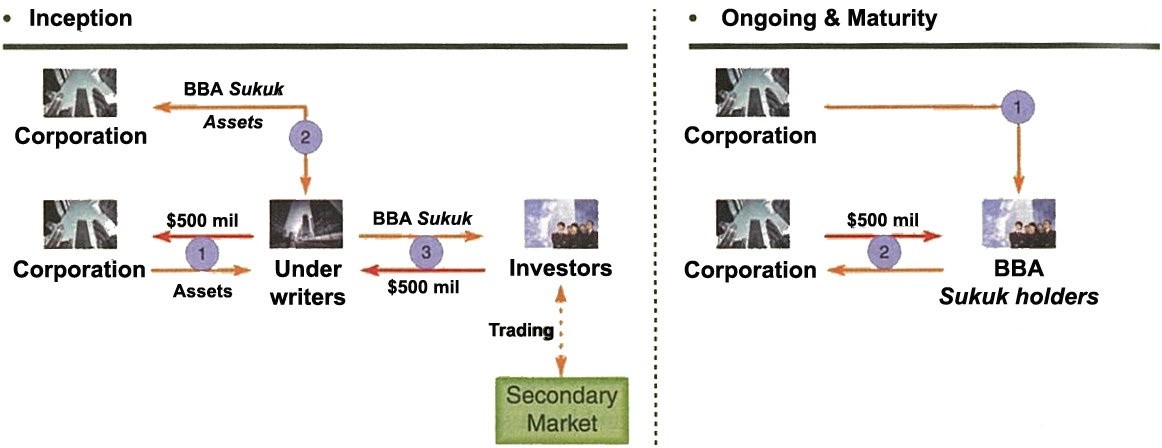

This sukuk is built through the principles of bay inah (sale and buy back) and bay al-dayn (sale of debt). Bay Inah refers to a transaction involving two back-to-back sales where the original seller sells the asset to the original buyer in cash, which the buyer then resells to the previous seller on a deferred basis at the original price with a profit margin. These transactions are carried out simultaneously at one time without handing over the traded assets. The validity of this principle is based on certain views in the schools of Syafie, Zahiri and Ibn Hazm because they think that the validity is sufficient in the form of a contract, not intention. However, this view is rejected by other scholars, among them Abu Hanifah, Malik and Ahmad ibn Hanbal who say that every act will be determined by intention based on the hadith of Umar's narration related to intention. Meanwhile, bay dayn is used because the asset sale contract involves deferred payment where the issuer will owe a certain amount whose value is displayed on the sukuk certificate. Sukuk certificates that have the responsibility to repay the debt, are usually offered at a discount price on the primary market to get the opportunity to increase funds. However, just like bay al-inah, this principle also has a long debate on its validity from the point of view of Sharia, especially the permission of Middle Eastern scholars including Sheikh Taqi Usmani. According to him, any price in the form of a debt (in this case, deferred payment is considered a debt) and if it is paid later with the addition of profit related to the money, then this situation is exempt from being linked to usury. However, this sukuk is very popular in Malaysia because of the interpretation of fiqh by Malaysian scholars that allows the practice. In fact, this BBA sukuk is very popular in Islamic debt securities in the local market of Malaysia which is estimated recently to be half of the debt securities issued in the local market (see Figure 5).

Beginning Stage: The diagram above shows the BBA sukuk structure built based on the principles of bay al-inah and bay al-dayn. If you look at the diagram, the company will sell certain assets that they own for $500 million in cash. The underwriters will then sell it back to the company for $600 million ($100 million to be paid in 10 installments along with $500 million to be paid at maturity, say 5 years. The company. The corporation proved the deferred payment earlier by issuing a BBA sukuk. The The underwriters will then sell the BBA sukuk to investors at a discount of $500.

Ongoing and maturity stage: The company will pay 6 instalments to sukuk holders. The sukuk holder will surrender the BBA sukuk for the purpose of redemption at the maturity date (say 5 years) for $500 million.

Sukuk Ijarah

Despite the controversy surrounding BBA sukuk, ongoing efforts have been made seriously to find a suitable sukuk structure and comply with the shariah requirements recognized by the global market to compete with senior unsecured bonds. The effectiveness of Ijarah sukuk was first tested around the year 2000 in handling small aircraft rental financing transactions. The structuring of the small aircraft rental is structured as follows:

i.Islamic financial financiers will establish a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV)

ii. The SPV will act as a representative/agent for the Islamic financier earlier

iii. Islamic financial financiers will provide funds to SPVs (agents)

iv. The SPV will use the funds to buy a small plane and register it in the name of the SPV

v. The SPV will lease the small pesawat to the airline for say 10 years with a rental payment every 3 months.

vi. The airline will buy the small plane at a set price from the SPV after the 10-year lease is over

vii. The SPV will receive rent payments every 3 months and distribute a portion of the payments to the Islamic financial financier as a shared profit.

viii. After the expiry of the 10-year period, the SPV will sell the aircraft to the airline at a set price and divide the funds received from the Islamic financial financier earlier as part of the investment principle.

Sukuk Ijarah is based on the rental (ijarah) of assets that can be rented. This type of sukuk usually has a maturity date of 6 months that has been determined at the beginning of the contract and is paid in arrears during the rental period. Sukuk ijarah is usually combined with the lessee's right to purchase the asset at the end of the rental contract (ijarah thumma al-bay'). Although it looks similar in rental structure in conventional finance, sukuk ijarah is bound to certain prerequisites which are:

i.the contract must be structured in accordance with Sharia and free from any prohibited elements

ii. the underlying asset must bring benefits to the user

iii. sukuk proceeds must be used according to shariah requirements

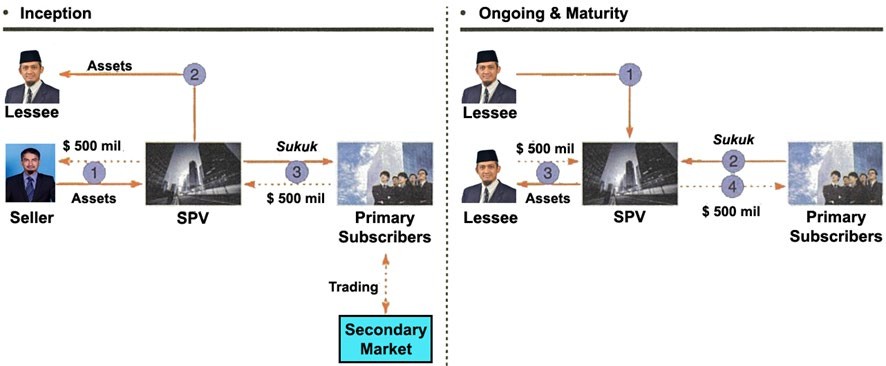

Sukuk Ijarah has been widely accepted in the global financial market and the fastest sukuk structure has been introduced in the market. Most countries such as Indonesia, Qatar, Pakistan and including Malaysia itself have structured most of their sukuk with Ijarah. Through this structuring, the SPV will issue sukuk to investors to acquire assets. The sukuk holder (investor) will then become the owner of the asset. The SPV will also sublease the asset to the lessee and receive leasing income from it. The leasing income will then be divided among the sukuk holders depending on the ownership rate on the asset. The leasing income rate can be determined on a floating or fixed basis depending on the agreement. Once the leasing date has reached maturity, the SPV will then resell to the original seller of the asset together with the proceeds from the original contribution amount (see Figure 6).

i.The diagram above is displayed to facilitate understanding of how the sukuk occurs through this structuring. At the initial stage, the seller sells certain assets it owns to the SPV for USD 500 million which is paid in cash. In many cases, the seller is also a lessee. (step 1)

ii. Then, the SPV leases the asset for 5 years. The lessee will also give a purchase undertaking to buy the asset on the maturity date of the lease. (step 2)

iii. The SPV then issued sukuk ijarah for 5 years to obtain funds of USD 500 million. (step 3) Ongoing and maturity

While the sukuk process is ongoing and reaching maturity

i.Lessee pays 6 monthly rentals to the sukuk holders. (Step 1)

ii. SPV distributes the 6-monthly rentals to the sukuk holders (Step 2)

iii. SPV sells the assets for USD 500 million at the end of 5 years pursuant to the Purchase undertaking (step 3)

iv. SPB distributes USD 500 million at the end of 5 years to redeem the Sukuk (step 4)

In the 90's era, the study focused more on the practical aspects of sukuk, whether it can be created practically in the environment of the existing economic and financial system or vice versa. Dualeh (1998) in his study has discussed about Islamic securities from the aspect of its practicality in the Islamic financial and banking system. Nisar (2007) and Gadar & Wilson (2006) briefly discuss the application, innovation, and performance of Islamic bonds or sukuk that have taken place since the time of its issuance. They are optimistic that Islamic securities will be able to move in tandem and compete with conventional securities if research continues.

In addition, there is also research and writing related to the advantages and potential of sukuk and its challenges in the financial markets. Writing in the field was done by Muhammad al-Bashir Muhammad al-Amin (t.t), Muhammad Ayub (t.t) and Michael Saleh Gassner (t.t). The study conducted by Asmak Abd Rahman (2000) is more focused on the role of Islamic debt securities and its implementation in the capital market in general. This study also discusses the capability of Islamic debt securities as an alternative financial instrument to conventional debt securities.

Tariq and Dar (2007) analyzes issues related to the structuring, risk, evolution as well as competition or competitive nature of sukuk to replace conventional bonds as the main instrument in the money and capital markets. This study is more focused on the risk management of Islamic securities due to changes in the current financial markets. The study published by the Islamic Research & Training Institute (IRTI) of the Islamic Development Bank was found to be more general and comprehensive. The study entitled Islamic Capital Market Product: Developments and Challenges (2005) examines the state of the Islamic capital market in the world as well as the ability of Islamic financial instruments to withstand risk. Another study entitled Financing Public Expenditure: An Islamic Perspective (2004) focuses more on how the use and role of sukuk as a medium to improve the standard of living of society and the economy of a country.

2.0 Sukuk market and its development

Sukuk is gaining attention in the world economy. Many countries have issued sukuk. As of 2020, 36 countries have issued sukuk. Asia is a major producer of sukuk (Abrorov & Imamnazarov, 2021). Aman et al. (2022) studied the factors influencing the development of the sukuk market. Per capita income, banking assets and money supply are among the main factors contributing to the development of sukuk. Many countries are beginning to show great interest in financing through sukuk as well as realizing the importance of developing capital markets. Shariah research also needs to be done to analyze the obstacles that can be overcome to create innovative sukuk products that are competitive and competitive. The study also suggested that other aspects such as buying and selling sukuk in the secondary market, sukuk returns and the role of sukuk in economic development be studied.

Jahan et al. (2021) discuss the opportunities and challenges of mobile sukuk for the purpose of social development in sub-saharan Africa where this instrument is also called as perpetual waqaf mobile sukuk (perpetual waqf mobile sukuk). It combines two main shariah principles, namely qard and waqaf. However, according to the researcher, this sukuk, if issued, can only be traded in the secondary market at par price and the sale and purchase takes place before the principal payment is paid by the issuer to the investor. Saeed and Aishath (2021) in turn studied the factors that influence the tendency of retail investors to subscribe to innovative sukuk such as caring sukuk during the COVID-19 pandemic. The characteristics of sukuk are one of the most important factors apart from attitude, social norms and perceived control that led to sukuk subscriptions by retail investors.

Hesham Amen (2021) in his thesis has studied the impact of sukuk including its issuance and liquidity on the stock market. Studies have shown that sukuk liquidity has an impact on stock market liquidity which is a positive relationship. Duqi & Al-Tamimi (2019) also studied the factors that influence the decision of investors in the UAE in subscribing for sukuk. The characteristics of the sukuk issued are among the main factors influencing investor decisions apart from religious factors. The study also revealed that the reason for the lack of liquidity of sukuk is the lack of market makers as well as the tendency of investors to hold until maturity. Rafay et al. (2017) presented a universal framework suitable for all sects for issuing sukuk. However, this study only focuses on sukuk ijarah. This study proves that it is not impossible to create a universal framework that can be accepted by all sects and without geographical limitations.

Classification of sukuk

In the Islamic capital market, sukuk instruments can be divided into the following divisions:

Asset-Based Sukuk

Most of the sukuk that are traded today are of this type, whether they are structured as ijarah, wakalah, salam, istithmar, murabaha or others. This sukuk is traded through the fixed income capital market along with conventional bonds.

Subordinate Sukuk

This type of sukuk is usually structured on the principles of ijarah, wakalah, mudharabah and musyarakah. Usually, a subordination structure is required by certain issuers who are looking to meet certain capital or debt ratio requirements. In a subordinated sukuk, the sukuk holders will have legal recourse only to the issuer but subordinate to all senior creditors and not have any recourse to the underlying sukuk assets.

Problem Statement

Preliminary studies on shariah issues in sukuk have focused on the ‘form vs substance’ polemic. The pattern of structuring and issuance of Islamic bonds in Malaysia, which is largely based on the bay 'al- 'inah and bay' al-dayn mechanisms, has led to many criticisms being leveled by analysts as well as sharia and economic experts both from within and outside the country. Saiful Azhar Rosly (2005) explains that differences of opinion arise due to the practice of different sects between Malaysia and the Middle East countries. Malaysia, which allows the practice of bay 'al-'inah and bay al-dayn contracts in the Islamic securities market, is based on the Syafi'i school. However, Muhammad Ayub (t.t) disagreed with the opinion and action that allowed Islamic bonds based on al-murabahah and BBA to be traded in the second market because it is said not to take into account the opinion of the entire Syafi’i school. Muhammad Ayub further explained that the fuqaha of the Syafi’i school only allowed the case when the debt was traded above par.

Saiful Azhar Rosly (2005) in another article suggested that the views of Islamic financial experts from the Middle East should be taken into account and considered if we want to improve the quality of Islamic financial instruments in the Islamic capital market in Malaysia not only from the economic aspect but also from the aspect tidiness of sharia legislation. Furthermore, Rosly and Sanusi (1999) argue that bond securitization based on al-muqarada contracts is seen as a good alternative to address the issue as well as attract large capital from Middle Eastern countries and avoid falling into the use of controversial contracts. The same thing was also raised by Mohd Hashim Kamali (2007) on the securitization practiced in Malaysia. Hashim opined that sukuk al-ijarah has the potential to be a more efficient and flexible financial instrument compared to al-murabahah and BBA besides being able to avoid using controversial contracts such as bay ’al-‘inah and bay’ al-dayn.

The increase in sukuk issuance is in line with the progress of innovation in the sukuk structuring process to meet shariah standards, laws and industry requirements. Although sukuk is seen to play a similar role to conventional bonds, these two instruments are different especially in their structuring process. Meanwhile, a bond is a document that proves the existence of indebtedness between the issuer and the bondholder along with the interest rate and it is issued without the underlying assets. On the other hand, sukuk requires the underlying asset in its structuring process. This puts sukuk more similar to asset-backed securities (Haneef, 2009). Most scholars are of the view that sukuk that fully meets shariah aspirations are ‘asset-backed’ sukuk. This is due to the exchange of asset ownership in a ‘correct’ manner through a sale and purchase contract between the asset owner and the sukuk holder. The sukuk holder also has full rights over the underlying assets.

However, due to the existence of several obstacles in structuring ‘asset-backed’ sukuk such as the difficulty of changing the name in the underlying asset grant from obligor to sukuk holder, tax issues and the negative implications of the ‘negative pledge’ clause have resulted in ‘asset-based’ sukuk. This sukuk only transfers beneficial ownership to the sukuk holder and puts the sukuk holder in the position of ‘unsecured creditor’. As a result, the sukuk holder has no rights over the underlying assets. Instead, they are only entitled to the cash flows generated through the underlying assets. Since both asset-backed and asset-based sukuk require an appropriate amount of assets to be used as the underlying assets, they are only able to attract certain entities, especially government or semi-governmental institutions because of these entities. It has sufficient assets to be used as the underlying asset in the process of issuing sukuk.

The difficulty of finding suitable assets to be used as underlying assets has eventually led to ‘blended-asset’ sukuk, followed by ‘asset-light’ sukuk. The existence of these two types of sukuk has provided an opportunity for corporate entities that do not have suitable or sufficient assets to raise funds through the issuance of sukuk in the Islamic capital market. Both of these types of sukuk offer flexibility in terms of the composition of the underlying assets required. The underlying assets for ‘blended-asset’ sukuk consist of a combination of tangible assets and intangible assets, while for ‘asset-light’ sukuk, they do not require the underlying assets in the initial structuring process. Among the shariah principles that are often used in structuring ‘asset-light’ sukuk are musyarakah and wakalah. Sukuk wakalah is the most popular structure in less than 10 years which accounted for 51% of the total issuance from 2010 to 2018. Sukuk wakalah is in demand because it provides greater flexibility in its structuring process and as an alternative to address the issue of lack of suitable assets to be used as underlying assets (Katterbauer et al., 2022).

Although the structuring of sukuk has undergone various innovations, it has not had a significant impact on the liquidity of sukuk in the secondary market. Not all sukuk can be traded on the secondary market at market prices as they are subject to certain conditions set by the respective shariah supervisory bodies (Ulusoy & Ela, 2018). The following are some of the resolutions issued by AAOIFI regarding the procedure for selling sukuk in the secondary market:

As shown in Table 1, although equity -based sukuk can be traded at market price once the project has commenced, it is still subject to the type and composition of the underlying assets. The majority of scholars especially from the Middle East have stipulated that the minimum percentage of real assets in the underlying asset component of sukuk is 33%, to enable these instruments to be traded on the secondary market at current prices. Some set it at 51%. Thus, any ‘asset-light’ sukuk structured using the principles of wakalah, musharakah or mudharabah must ensure that this ratio is met throughout the listing or issuance period to enable it to be traded at market prices in the secondary market.

But in reality, it is quite difficult for a special purpose vehicle (SPV) or any entity that manages the fund or project to meet the prescribed ratio. For example, the Dubai Metal & Commodity Exchange (DMCE) Sukuk issued in 2005 used the musharakah principle, where one party contributed land worth USD48 million, while investors contributed USD 300 million, bringing the total value to USD348 million. Thus, the cash to total asset ratio is 86%. The funds raised will be used to build three towers. If all the funds have been spent on the development project by way of payment to the contractor, the ratio of receivables remains above 33%. The receivables are from the sale of units in the tower that have not yet been built. More than 80% of the units of the two towers had already been sold before the sukuk was issued (Haneef, 2009). This stipulation makes ‘asset-light’ sukuk highly unlikely to be traded due to not being able to meet the percentage of real assets (Haneef, 2012). This has indirectly caused the secondary market for sukuk to become increasingly inactive due to the lack of liquid financial products on offer and the lack of participation from retail investors and corporate institutions.

As explained earlier, based on the rulings set by the AAOIFI as well as the majority of Middle Eastern scholars, sukuk whose underlying assets consist of cash, receivables or debt only, then the instrument can only be sold at par. However, for sukuk whose underlying assets are mixed, for example consisting of 33% cash and 67% physical assets such as buildings and factory equipment, then they can be sold at market or current prices. What about sukuk whose underlying assets are the same as previous sukuk even though the cash ratio is only over 33%? Does it have to be sold according to the cash ratio or is there another mechanism in determining its selling value? To date, there has been no clear ruling on the value and marketability of the instrument from international shariah supervisory bodies.

Research Questions

This study focuses on shariah issues in sukuk liquidity in the secondary market. Thus, the research question of this study related to:

a) What is the reason for the lack of liquidity of sukuk in the secondary market?

b) What is the suitable universal framework for issuing sukuk that can be accepted by all sects?

Purpose of the Study

This study aims to identify the reason for the lack of liquidity of sukuk in the secondary market as well as the tendency of investors to hold until maturity. To be specific this research focuses on the mechanism in determining sukuk’s selling value because to date, there has been no clear ruling on the value and marketability of the instrument from international shariah supervisory bodies. This study also aims to propose a universal framework suitable for all sects for issuing sukuk. This study will prove that it is not impossible to create a universal framework that can be accepted by all sects and without geographical limitations.

Research Methods

Using a qualitative methodology, data was collected and analysed for this study. The research focuses on efforts to gather non-numerical data that can offer in-depth knowledge on the backdrop subject (Cresswell, 2013). Additionally, it does so without altering any actual circumstances in order to grasp the true status of a phenomenon in a particular setting (Patton, 2002). The study's content analysis strategy aims to accomplish the necessary goals. In qualitative investigations, content analysis views more text as a personal, internal reading of meaning. According to Graneheim and Lundman (2004), content analysis has a distinct benefit when assessing contents in light of context and procedure. While the process component comprises the methodical and recurring process of text interpretation, the context aspect is implicitly observed through the main content (latent content). Then, this information is processed inductively, beginning with in-depth observations in broad circumstances before generating more specialised opinions and ideas (Bennard, 2011). This method is used to define the issue or phenomenon being examined, and the research's findings are then applied to the development of specific conclusions that are pertinent to the issue being studied.

While applying the study, a qualitative approach is used in which the analysis of the original book of fiqh and a review of past studies by applying the method of content analysis. Content analysis has been defined as a systematic, replicable technique for compressing many words of text into fewer content categories based on explicit rules of coding. The most common notion about the content analysis is simply means doing a word-frequency count. The assumption made is that the words that are mentioned most often are the words that reflect the greatest concerns. Thus, the words counting is coded from the past literatures to examine the shariah issues that are hurdles to the industry in determining the nature of underlying asset for the sukuk marketability so that the liquidity problems may be resolved.

Findings

Contemporary scholars differ in determining the basis of shariah judgments about the sukuk sales standards of its underlying assets which are mixed in the secondary market. Methods such as al-asalah wa al-tab’iyah, al-aghlabiyah, al-akthariyah, syakhsiyah al-iktibariyah and mud ajwah are often discussed among current shariah and muamalat experts.

Syaksiyah Iktibariyah

Muhammad Ali al-Qari argues that modern companies are based on the concept of legal personality (syaksiyah iktibariyah). Thus, the assets of the company are owned by legal personalities, not shareholders. Shareholders are only the owners of rights or have ownership over the legal personality. Since shares are considered not to be a joint part of the company's assets, then shares and sukuk can be traded without having to look solely at the composition of the assets (El-Qary, 1998). On the other hand, it is sufficient to just look at the original goal and the business is halal. He also pointed out in another paper that the definition of shares put forward by Majma ’Fiqh Islami is inconsistent with the description of shares understood in the modern context (El-Qary, 2015). Dr Adil Awadh Ba Bakr who also supports this principle stressed that the determination of sarf and debt law to sukuk traces the principle of syakhsiyah iktibariyah, while from a legal perspective, there is a difference of responsibility and liability between sukuk holders and companies or institutions. This results in at the same time making investments in the capital market ineffective. Companies also find it difficult to determine the ratio of cash, debt and real assets at all times (Bakr, 2013).

Mud Ajwah

The issue of buying and selling sukuk in the second market was also analyzed by Rafe Haneef (2012) who suggested that the mud ajwa case discussed by past jurists can be used as a backup in determining the minimum rate of value of sukuk traded. He sees this mud ajwah method can be considered as a backup in determining the liquidity ratio of sukuk, especially sukuk issued without tangible assets or the ratio of small real assets compared to intangible assets such as sukuk wakalah and sukuk musharakah. Yet, asserts that the mud ajwah method applies when both exchange assets (goods and prices) exist when the contract is entered into. If one does not exist, then this method does not apply (Alkhamees, 2017). Mohamad et al. (2018) also concluded that the mud ajwah method is seen as relevant if it involves ribawi goods physically. As for debt (debt) or receivables (receiveable) is seen as more suitable to match the case of selling slaves and their property. Redzuan et al. (2021) are of the view that the mud ajwah method can be used as a parameter to buy and sell shares in the capital market or exchange if the instrument is not considered as urudh tijarah (merchandise) instead the maliyah (property) nature of the stock is determined based on its underlying assets.

Al-Asalah Wa Al-Tab’iyah & Al-Ghalabah

Ali Ahmad Nadvi discusses the tab’iyah method and its implications for stocks and sukuk whose underlying assets are mixed. He is of the view that the tab'iyah method can be made the core, without having to look at any ratio. He sees this practice on the basis of rukhsah and looks at qasd ijmali (objective holistically) rather than tafsili (objective specifically). Yet it does not preclude the use of the method of aghlabiyah if a component is always dominant so as to drown the qasd (Nadvi, 2006). Al-Qurrah al-Daghi (2013) discusses several mechanisms in resolving the issue of buying and selling shares and sukuk whose underlying assets are mixed. He has discussed the method of legal personality, the method of al-kathrah wa al-ghalabah, al-asalah wa al-tab’iyah as well as the method of al-takharuj. He is of the view that the principle of al-asalah wa al-tab'iyah is most suitable as the basis for a solution for the sale of shares and sukuk (Al-Qurrah al-Daghi, 2013). Based on this principle, the marketability of shares and sukuk by looking at the main activities or core of the company. For companies whose main activity is business involving assets, then shares and sukuk can be traded at market prices without having to look at the asset -debt ratio.

Asad and Anwar (2019) also stressed the same point that the principle of al-asalah wa al-tab’iyah is more practical in solving this problem provided the shares are wanted while cash and debt are subsidiaries. Yusuf bin Abdullah al- Syubaili argues that the principle of Al-Tab'iyah is applied specifically to sukuk musharakah & mudarabah whose activities are progressive. Company assets are considered to be tabi ’to the company’s activities. Furthermore, the company is also considered as syakhsiyah iktibariyah. But this principle was born due to the existence of progressive activities. The purpose of a buying investor is to engage in the company’s activities and not to acquire the company’s assets. Therefore, when the use of funds begins, then cash and debt are considered tabi '(subsidiary), therefore, there is no need to look at the ratio and there is no need to look at the rules of bay al-sarf and bay al-dayn. He is also of the view that the principles of Al-Aghlabiyyah are applicable to other than sukuk musharakah & mudarabah. Rules of its sale by looking at the dominant element. If the physical assets, benefits and rights exceed 50%, then there is no need to comply with the law of sale and purchase bay al-sarf (Habib et al., 2015).

Mohamad et al. (2018) discuss the principles of al-asalah wa al-tab’iyah, al-aghlabiyyah and al-akhtariyyah in the context of stocks. Discussions are more focused on stocks. He concluded that for mixed instruments such as a combination of cash, debt and receivables (receiveable) is seen to be more suitable to be matched with the case of selling slaves and their property and not with the mud ajwah method. Sami Ibrahim al-Suwailem also discusses the methods of al-ghalabah and al-tab’iyah in muamalat and its application to stocks, unit trusts and sukuk. He is of the view that sukuk should follow the method of al- aghlabiyah. The sukuk structuring process is different from stocks. SPVs created in the sukuk structuring process do not have actual capital, instead only to maintain the related assets. Therefore, it is tabi '(subsidiary). He thinks that actual capital is matbu' (Alkhamees, 2017).

Conclusion

The question of error in determining the appropriate shariah principles is important to discuss in the operation of Sukuk. However, the shariah principles embedded in the product should take into account commercial factors such as liquidity friendliness to investors and sukuk issuers especially in the secondary capital market. The secondary market is important for sukuk investors in obtaining financing because there are still many small companies that are still unable to issue sukuk in large quantities due to small asset ownership factors. With a variety of solutions or those adapted from the theories and problems of fiqh will be able to boost the second market due to almost all sukuk whose underlying assets are mixed and thus give confidence to investors including institutions that do not have sufficient real assets to invest and issue sukuk.

Acknowledgments

This paper is one of the research output made for fulfilling the TEJA Research Grant requirement under the project entitled, ‘Perimeter of Sukuk Marketability in The Secondary Capital Market’ - GDT2022/1-3.

References

Abrorov, S., & Imamnazarov, J. (2021). Islamic Fintech Instruments: New Opportunities for Digital Economy of Uzbekistan. In The 5th International Conference on Future Networks & Distributed Systems (pp. 663-667).

Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions Accounting (AAOIFI). (2007). Auditing & governance standards (For Islamic Financial Institutions), Shariah Standards. Manamah.

Ahmad, N. (2020). The Sukuk Industry in Malaysia. Islamic Finance as a Complex System: New Insights, 127.

Alkhamees, A. A. (2017). A critique of creative Shari'ah compliance in the Islamic finance industry. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

Al-Qurrah al-Daghi, A. (2013). Athar al-ikhtilaf bayna al-syakhsiyyah al-tabi‘iyyah wa al-syakhsiyyah

al-i‘tibariyyah fi al-ahkam al-fiqhiyyah li mustajadat al-masrifiyyah al-Islamiyyah wa nahwiha [The effect of the difference between the natural personality and the legal person on the jurisprudential rulings of the Islamic banking]. Retrieved April 5, 2022, from http://iso-tecdemos.com/islamfiqh/dataentry/ar/node/376

Aman, A., Naim, A. M., Isa, M. Y., & Ali, S. E. A. (2022). Factors affecting sukuk market development: empirical evidence from sukuk issuing economies. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management, 15(5), 884-902.

Asad, M., & Hafiz, M. A. (2019). Shariah Maxim of Originality and Dependency and Their Modern Applications in Commercial Transactions. Journal Al-Basirah, 8(1), 61–80.

Asmak, A. R. (2000). Peranan Hutang Sekuriti Swasta Islam Dalam Pasaran Modal Di Malaysia. Disertasi Sarjana Syariah, Akademi Pengajian Islam Universiti Malaya.

Bakr, A. A. B. (2013). Completion of the Topic of Islamic Sukuk – A Comparative Study of Legal, Practical and Jurisprudential Aspects. International Islamic Fiqh Academy Conference. https://docs.google.com/viewer?url=https://www.muslim-library.com/dl/books/ar5597.pdf

Bennard, H. R. (2011). Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Aita Mira Press.

Cresswell, T. (2013). Geographic thought: a critical introduction (Vol. 8). John Wiley & Sons.

Dualeh, S. A. (1998). Islamic securitisation: practical aspects. In World Conference on Islamic Banking, Geneva (pp. 8-9).

Duqi, A., & Al-Tamimi, H. (2019). Factors affecting investors’ decision regarding investment in Islamic Sukuk. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 11(1), 60-72.

El-Qary, M. A. (1998). Legal Personality with Limited Liability: An Economic Jurisprudence Study. Islamic Economic Studies, 5(2), 9–60.

El-Qary, M. A. (2015). Jurisprudential Adjustment of Shares of Joint Stock Companies. The Sixth Jurisprudential Shura Conference for Islamic Financial Institutions.

Etudaiye-Muhtar, O. F. (2016). The Effect of Financial Market Development on Capital and Debt Maturity Structure of Firms in Selected African Countries. Universiti Malaya.

Gadar, K., & Wilson, R. (2006). An Empirical Analysis of Islamic Bond Selection by Individual Dealers: Evidence from Malaysia. Review of Islamic Economics, 10(2), 55-73.

Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse education today, 24(2), 105-112.

Jahan, S., Muneeza, A., & Baharuddin, S. H. (2021). Islamic capital market for social development: innovating waqf mobile sukuk in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Habib, F., Laldin, M. A., & Lahsasna, A. (2015). A Fiqhī Analysis of Tradability of Islamic Securities. ISRA International Journal of Islamic Finance, 7(1), 159-167.

Hashim, K. (2007). A Shari’ah Analysis Of Issues In Islamic Leasing. Journal Of King Abdul Aziz University: Islamic Economic, 20(1), 3-22.

Haneef, R. (2009). From “asset-backed” to “asset-light” structures: The intricate history of sukuk. ISRA International Journal of Islamic Finance, 1(1), 103-126.

Haneef, R. (2012). The Case For Receivables-Based Ṣukūk: Convergence Between The Malaysian And Global Sharīʻah Standards On Bayʻ Al-Dayn? Isra International Journal of Islamic Finance, 4(2), 119-140.

Iqbal, Z., & Mirakhor, A. (2011). An Introduction to Islamic Finance: Theory and Practice. John Wiley & Sons.

Katterbauer, K., Syed, H., Cleenewerck, L., & Genc, S. Y. (2022). Robo-Sukuk pricing for Chinese equities. Borsa Istanbul Review, 22(5), 854-860.

Mohamad, S., Habib, F., & Salim, K. (2018). Criteria for determining the Shari'ah compliance of shares: a fiqhi synthesis. ISRA.

Muhammad, M., Sairally, B. S., & Habib, F. (2015). Islamic Capital Market: Principles & Practices. https://ikr.inceif.org/handle/INCEIF/2122

Nisar, S. (2007). Islamic Bonds (Sukuk): its introduction and application.

Nadvi, A. A. (2006). The Rules of “Dependency” and Their Impact on Financial Contracts: Islamic Economic Studies. The Islamic Research and Training Institute, 14, 1–62.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: A personal, experiential perspective. Qualitative social work, 1(3), 261-283.

Rafe, H. (2012). The Case for Receivable-Based Sukuk: Convergence between the Malaysian and Global Shariah Standards on Bay al-Dayn. ISRA: International Journal of Islamic Finance, 4(2), 53-68.

Rafay, A., Sadiq, R., & Ajmal, M. (2017). Uniform framework for Sukuk al-Ijarah–a proposed model for all madhahib. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research.

Redzuan, M. A., Sharif, D., & Khir, M. F. A. (2021). Mud Ajwah Issues and Its Implications on Current Islamic Financial Practices: Literature Highlights. Jurnal'Ulwan, 6(3), 37-48.

Rosly, S. A., & Sanusi, M. M. (1999). The application of bay’al-’inah and bay’al-dayn in Malaysian Islamic bonds–an Islamic analysis’. International Journal of Islamic Financial Services, 1(2), 3-11.

Saeed, A. N., & Aishath, M. (2021). Investment Decisions in Digital Sukuk in the time of COVID-19: Do Tax Incentives Matter? Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment.

Saiful, A. R. (2005). Critical Issues on Islamic Banking and Financial Markets: Islamic Economics, Banking and Finance, Investments, Takaful and Financial Planning. Dinamas Publishing.

Tariq, A. A., & Dar, H. (2007). Risks of sukuk structures: implications for resource mobilization. Thunderbird International Business Review, 49(2), 201–223.

Ulusoy, A., & Ela, M. (2018). Developments in Taxation of Sukuk in the World and Suggestions for Turkey.

Yıldırım, S., Yıldırım, D. C., & Diboglu, P. (2020). Does Sukuk market development promote economic growth? PSU Research Review, 4(3), 209-218. https://doi.org/10.1108/PRR-03-2020-0011

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

18 August 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-963-4

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

1

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1050

Subjects

Multi-disciplinary, Accounting, Finance, Economics, Business Management, Marketing, Entrepreneurship, Social Studies

Cite this article as:

Sharif, D., Redzuan, M. A., Meerangani, K. A., & Mustafar, M. Z. (2023). An Overview of Sukuk Liquidity Market Issues in the Shariah Perspective. In A. H. Jaaffar, S. Buniamin, N. R. A. Rahman, N. S. Othman, N. Mohammad, S. Kasavan, N. E. A. B. Mohamad, Z. M. Saad, F. A. Ghani, & N. I. N. Redzuan (Eds.), Accelerating Transformation towards Sustainable and Resilient Business: Lessons Learned from the COVID-19 Crisis, vol 1. European Proceedings of Finance and Economics (pp. 224-241). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epfe.23081.19