Abstract

Second language acquisition (SLA) has always been connected to interactive methods and environments introduced by educators worldwide, which is why sports was one of many domains that has been paired with SLA. Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) is one of the methods used to bridge the gap between SLA and sports. Past studies have proven that CLT is significantly effective in improving students’ second language (L2) proficiency levels. This pilot qualitative research aims to determine if CLT is effective in improving university students’ English communication skills significantly by playing volleyball in a casual setting. This research utilizes the participant observation method. 11 Malay undergraduates from Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) Melaka were observed whilst playing volleyball in a recreational setting. The pilot research was carried out for 51 days in the span of 14 weeks. The in-game communications were recorded and described in field notes. The data were then systematically arranged and transcribed before being triangulated. The analysis of the triangulated data showed that in 14 weeks’ time, most of the students’ English-talking time and word count increased significantly. In addition, their frequency of initiating in-game communications in English also showed gradual increase. This research has proven the successful achievement of the research objective, which is CLT is effective in improving university students’ English communication skills significantly by playing volleyball in a casual setting.

Keywords: Communicative language teaching, volleyball, participant observation method

Introduction

The connections of second language acquisition (SLA) and sports have been discussed by various academic researchers from both domains – which generally implies that it is not uncommon for language educators to incorporate sports contents or inculcate sports habits within their means of teaching a second language (L2). Back in the late 2000s, it was already highlighted that earlier literature that focused on SLA had very rarely connected it with physical games. While it has been fairly common for researchers in the early millennium to associate physical games with early childhood education, Tomlinson and Masuhara (2009) elaborated that almost none have associated physical games with SLA. Although there were earlier studies that correlate language learning with sports, such as browsing through sports sections in the local newspapers and interactive learning experiences by reading sports news headlines , these studies did not involve the students physically playing the sports.

Problem Statement

It was recently reported that only a few academic works have been published on the subject or in-depth analysis of language usage in sports . Specifically for Malaysia’s higher education setting, high school graduates must first pass their English subject for their national high school exam aptly named “” before they can register themselves as an undergraduate in a Malaysian public university – one of which is Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM Melaka, 2022), the current university of the respondents for this research. As Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) students, they would have earned at least a “” (meaning pass / satisfactory) on their high-school test as one of the minimal prerequisites for university entrance. This also indirectly fulfills the objective of this research because the students are not English native speakers, trained professional experts in language communication, or even highly experienced students is a communication or linguistic program.

Communicative Language Teaching (CLT)

In the early 1990s, academic experts perceived that communicative language teaching (CLT) had become a concept for approaches and syllabuses that encompass both the objectives and steps of classroom learning, for curriculum implementation that considers capabilities in terms of active participation and aims to improve future SLA research studies to catalyse its advancement. CLT is flexible by nature and there are simply too many ways for it to be manipulated in order to make it suitable and efficient for every educator’s student profiles and their respective learning environments. Hence, the researcher has chosen to try adapting CLT by playing sports – and volleyball was chosen; as it is one of a few team sports that involves significant amount of both verbal and non-verbal in-game communications betwixt all the players (D’Elia et al., 2020).

Volleyball

As volleyball has existed for over a century, its origins are pretty basic. According to historical documents, William G. Morgan, who created volleyball in 1895, had a sudden inspiration of providing an alternate physical exercise for those who felt basketball's 'bumping' or 'jolting' excessively demanding. William G. Morgan surveyed the available athletic games and selected those that he believed best fit his objective .Volleyball’s regulations varied according to region; nonetheless, national titles were held in a number of nations. Thus, volleyball developed into an increasingly professional sport requires a great deal of physical and technical ability . Currently, it is believed that volleyball is being played by over 800 million people worldwide.

Learning in sports – recent theory and recommendations

Recently, researchers have theorised that learning in sports may help promote critical thinking and an openness to experience learning (Ronkainen et al., 2021). Language educators and researchers typically correlate non-linguistic domains with teaching English by engaging English for Specific Purposes (ESP) philosophies, which also can also include sports. It has been recently recommended that teaching English with the integration of sports element needs to be improvised not just at university levels but also at school levels (Mendes et al., 2021) and professional working levels (Pranoto & Suprayogi, 2020). Hence, this research also addresses the recommendations stated previously.

Research Questions

This study questions whether CLT is effective or not in terms of improving university students’ English communication skills significantly by playing volleyball in a casual setting.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to determine the effectiveness of CLT in improving university students’ English communication skills significantly by playing volleyball in a casual setting.

Research Methods

Prior to the commencement of this pilot research, the potential students (as volleyball players) must be able to converse volleyball’s in-game communications in English; and, these conversations must meet certain English proficiency levels. The general prerequisite for the sample’s English proficiency had already been determined to be deemed acceptable (as mentioned in Problem Statement paragraph previously).

![Basic positions [(a)] and their roles [(b)] in volleyball (MIT Women's Volleyball Club, 2008).](https://www.europeanproceedings.com/files/data/article/10129/17629/IRoLE2023F070.fig.001.jpg)

Figure 1 shows volleyball players’ basic positions and their respective roles; the students were already familiar with this setup. The positions include setter, outside hitter, middle blocker, opposite, and libero . For the in-game communications, the students were expected to verbally communicate with each other frequently because they were not trained professionals who can systematically and easily play using various tactical attacks and planned formations without any verbal discussions. As the game requires repetitive, back-to-back movements and cooperation of all the six players in both teams respectively, the students would have to communicate continuously to ensure they can coordinate their intended plays; these involves all the basic plays in volleyball (serve, dig, set, spike, block, point system, and rotation) being discussed, called out, planned, argued, and celebrated – mainly verbally . Hence, three methods were utilized to collect the data from the in-game communications; observation, field notes, and unstructured interviews.

Data Collection

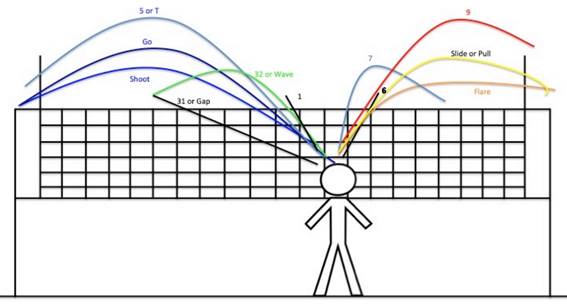

Being actively involved in the recreational volleyball matches as a presumed foreign lecturer who did not understand Malay, the students had no choice but to speak English to communicate with the researcher whilst playing volleyball. This natural setting as a fellow recreational volleyball player enabled the researcher to verbally communicate with the students during the matches and actively observe their English communication abilities at the same time. The pilot research was carried out for 51 days in the span of 14 weeks; the observation days were not pre-planned with students to ensure data validity and reliability. As it turned out, researcher only happened to be available during the playing days in Week 1, Week 5, and Week 10. Hence, these days were used to collect the data needed. The in-game communications were recorded and described as field notes in a smartphone app during the interval periods in between the matches. Every conversation had would revolve around actual volleyball game plays, such as positions, strategies, instructions, suggestions, questions, and celebratory cheers. Aside from the volleyball basics listed earlier, some plays could only be explained using diagrams in Figure 2.

Volleyball tosses by a setter.

Participant Observation

A quick search in Google Scholar using the phrase “participant observation in sports research” revealed only three relevant results out of 473,000 results found without any specific range of publication year (Google Scholar, 2022). The lack of prior qualitative studies that utilized participant observation method for sports research has been one of the two main reasons of why this method was selected. The researcher, who happened to have more than 12 years of experience as a semi-professional volleyball player, an amateur volleyball coach, and a local university’s volleyball club advisor, had already possessed the necessary background knowledge and playing skills of the sport – this made the researcher a perfect ‘participant’ for this observation. Taylor et al. (2015) had thoroughly elaborated that participant observation researchers need to “blend into the woodwork”; in this research, the researcher’s past experiences and skills have proven that he had already grasped the required understanding of the settings. Another crucial reason for selecting participant observation is: there was already a presumed, mistaken perception amongst the students that the researcher is a foreigner who apparently did not understand Malay – the students’ first language. Hence, the researcher had decided to stay in the presumed character and joined the recreational volleyball sessions as a ‘foreign lecturer who can play volleyball’. This had proven to be extremely beneficial to this research because even though they still used Malay significantly as per their constant interactions with each other, the students naturally had to use English whenever they have to converse with the researcher. With these reasons in mind, the researcher even volunteered as a setter to promote more one-to-one communications with the students because setters control all the major offensive patterns. All these unplanned settings not only rejected potential bias elements, but also strengthen the validity of the data – because the actual representativeness of the linguistical features used could be assured in real-time settings .

Field notes

As suggested and explained by Taylor et al. (2015), researchers need to be critical when it comes to using field notes for contemporary qualitative research; primary concerns include how notes are recorded, what kind of notes are being kept, the possibilities of requiring informed consents from certain parties, and organization of data categories. As recommended by many past qualitative research experts, the researcher had used abbreviations, pseudonyms and unique keywords to protect the students’ privacy and confidentiality. In addition, the researcher had never asked anything concerning their demographic details (age, gender, hometown, etc.) or student profile (student ID number, current semester, program, course, etc.) to further reduce the possibility of the students’ identities being revealed in the future. By using a default, factory-setting ‘Notepad’ smartphone app to record notes during the short interval in between sets, most descriptions and conversations could be recorded fairly easily because of the categorized outlines made prior to playing the games. As these data were only used in this research solely to improve the students’ English proficiency levels, the researcher viewed that no informed consents were required from the students. Apart from the hidden identities and the sole objective of improving the students’ English proficiency levels, the researcher also perceived the observation sessions as an extension of learning more on how to educate the students better – these were the highlighted representations of the data collected .

Unstructured interviews

For this study, the researcher decided to proceed with unstructured interviews because according to Alsaawi (2014), this method’s flexibility provides lots of leeway and freedom for the students in answering them. This would also naturally cause minimal interjections for and from the researcher whilst asking questions. Alsaawi (2014) summarized that apart from the reasons mentioned previously, it would be efficient if the researcher has singled out the focus of then intended domain – in this case, the researcher only asked questions pertaining to volleyball skills and game plays. The researcher also used a specific variation of unstructured interviews that does not include having pre-planned questions – as explained by Adhabi and Anozie (2017). They called it non-directive interview, which signifies that the researcher would already have a strong grasp of the intended research contexts and the ability to control the directions of questions towards the relevant matter at hand – volleyball skills and game plays . As an example: if the researcher (as the setter) would be planning for an attack, he would have aptly instructed both outside hitter and opposite to prepare for A5 and D9 tosses respectively whilst quickly reminding the ones behind the 3-meter line to receive and pass the first ball up high towards the setter. A normal conversation would be expected to sound something similar to the interactive dialogue below:

Setter: “Outside hitter, listen up! You’ll get an A5 after this.”

Outside hitter: “Alright setter, I’m open!”

Setter: “Opposite, get ready for a D9 toss. That’ll be yours!”

Opposite: “I’m ready! Just give it to me!”

Setter: “The others! Make sure you pass the ball up high so that I can toss to the hitters!”

The others: “OK! We’ll give you a nice pass!”

In-game conversations like the ones prepared above would have been continuously uttered and shouted depending on the real-time rotations and offensive / defensive formations. Playing as the setter, the researcher would converse non-stop throughout the matches for both (i) play-making strategical awareness, and (ii) collecting data for further analysis. On average, at least four volleyball matches could be completed in the span of roughly two hours every day. The length of each match can easily differ from each other depending on several factors such current temperature and weather conditions (windy condition, bright sunlight, etc.), individual performances and volleyball rallies. Hence, matches could end as fast as 15 minutes and could go up to 30 minutes per match. All the relevant data from observation, field notes, and unstructured interviews would later be triangulated to increase the credibility and validity the future results that would be generated by further analysis with thematic coding.

Samples

For this research, 11 Malay undergraduates from Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) Melaka were observed whilst playing volleyball in a recreational setting. Their actual academic levels were not ascertained, but they could most likely be a mixture of groups of students from either a Diploma program or a Bachelor’s Degree program or both. All of them were regular, recreational volleyball players who would play volleyball at the university’s public sport center late in the afternoons almost every day regardless of whether it would be weekdays or weekends. Figure 3 displays the layout of an official volleyball court:

As no demographic details or student profiles were recorded, the only known similarity that can be confirmed visually was their passion in playing volleyball. It has been duly ascertained, however, that none of them (i) were non-Malay students, because all UiTM campuses only have Malay undergraduate students; and (ii) had an advanced English proficiency level; because everyone whom the researcher talked to could not form complete, grammatically – correct sentences as their verbal replies. These confirmations were within expectations – as explained in the methods’ introductory paragraph earlier. In terms of individual volleyball innate talents and physical skills, everyone’s level differs somewhat slightly. All of them had differing physical heights – from as short as 145cm to as tall as 180cm. They also showcased various levels of body conditionings, fitness, jumping abilities, and physical strengths. If they were indeed sharing a similarity in these aspects, it would be the notion that their individual skills as volleyball players were not up to par compared to the researcher’s own volleyball skills who has played as a semi-professional volleyball athlete for several years.

Findings

After the data have been collected, the researcher triangulated them into separate elements of codes accordingly. The main objective was to find out if they would have shown improvements in terms of the words, phrases, and sentences that they uttered whenever they communicated with everyone in the team / court during those multiple volleyball sessions in the span of 14 weeks. All Table 1, Table 2 dan Table 3 will showcase all the codes mentioned / repeated collectively by all the 11 students. The elements to be coded were volleyball jargons / phrases, volleyball verbs used, and sentences used. The expected improvements of English proficiency levels of every student were not going to be compared individually with each other. The findings would then be interpreted with open coding and axial coding ; the final stage would involve summarization process with content analysis.

Data interpretations and discussions

From the triangulated data, it can be initially summarized that the students gradually uttered not only more words and phrases, but also sentences to communicate with everyone during the matches. The sentence structures in Week 1 showed that they had uttered short and brief sentences; most of them were simple sentences. Week 1’s sentences showed a low average of number of words used in a sentence – the numbers range in single digits. The vocabulary used was basic in nature and the level of confidence shown was not high. Awkwardness was detected whenever the researcher asked questions or initiated communications in the court. Some of them hesitated to answer and started to look at their teammates for assistance in giving responses. Their awkward smiles and stuttered speeches also gave the impressions that they were not used to conversing with a supposed foreigner – or perhaps, it was because they were simply not used to conversing in English outside of their classrooms. There were also a number of instances which reflected their lack of awareness in utilizing proper modal verbs (such as can, must, will, should, etc.) and subject-verb agreements (SVA; such as is and are with the correlating verbs). In addition, they also incorporated a few localized volleyball jargons to indicate certain events or situations; all of which were not recognized based on Fédération Internationale de Volleyball (FIVB) standardized guidelines. For this issue, it also proved that they never had any prior professional experience as a volleyball athlete.

However, starting from Week 5, the lengths as well as the types of sentence structures spoken increased steadily. The average word count in their sentences reached double digits; their vocabulary ranges also showed improvements in terms of the variety of volleyball jargons used such as ‘floater’, ‘pancake’, ‘dummy’, and ‘cross’. Most probably because of stronger resolves and increased familiarity with the researcher in court for the past week, the students seemed as if they had a booster for confidence. They had begun initiating conversations using the second language instead of their mother tongue before they gave lengthier verbal responses and more variations of non-verbal feedbacks. They even elaborated specific instructions for certain plays and movements by using various volleyball jargons, particularly for offensive plays such as ‘fast ball’, ‘open ball’, ‘sub ball’, ‘back line ball’, jump serve, and ‘dump’. This proved that the students not only had the passion to improve their skills, but also the drive to improve their English communication skills by not being ashamed to try initiating conversations and giving responses.

Week 10 showed extensive progress if it was compared to the data collected in Week 1. Not only they started using significantly more jargons and longer sentences, but they also voiced out their responses with loud inflections. Aside from more varied and longer sentences (compound sentences and complex sentences could also be heard), they also asked questions and gave specific instructions with relevant recommendations. As an example, when a player advised the other teammates with “Remember guys, if you stay in front, you must take care of front zones only. Let others at (the) back receive high serves. All (must) bend down!” and / or requested a specific toss with “Setter, I prefer if the toss is close to the net and not far from the net”, these possibly showed either comfortability, spontaneity, or even confidence in L2. Hence, they have reached a level where they were able to inclusively (i) communicate with better English proficiency levels, and (ii) focused on the intensity of the actual matches. At this stage, they no longer needed to pause and think of a proper response in English – they could do it almost naturally without any reinforcement or assistance by the researcher.

Conclusion

These analyses summarized that for this pilot research, the adapted CLT utilized in the volleyball matches had worked quite well. After a period of time, the students’ linguistic progresses could easily be evaluated by observing and listening to their verbal responses. In addition, they even managed to somehow converge these linguistic progresses within their efforts of improving their individual-and-team volleyball plays and skills. As a bonus point, their affective domains could be observed to have improved quite significantly as well; which could be deduced from their stronger confidence in communicating in English, they had better team chemistry whilst playing, and they signalled clearer awareness on their respective in-game roles and formations. Apart from these findings, the researcher had also summarized two notable limitations which could be adjusted or rectified in future undertakings. The most obvious one would be the scope of the vocabulary used – which revolved only about volleyball. The specific nature of the sport made it almost impossible to generalize most of the linguistic progresses into applications in real-life contexts. Another limitation factored in the participation of the researcher – which was only possible because of the researcher’s background profile as an athlete. Based on the discussions stated previously, it is highly recommended that the practice of adapting CLT to be continued by language educators. Adapted CLT approaches have been proven to be not only effective for SLA, but also for students’ intrinsic affective domains. Aside from sports, CLT can also be adapted with numerous other domains which can be highly technical too, such as aircraft maintenance (Abdul Samad et al., 2022c), manufacturing technology health (Abdul Samad et al., 2022b; Ya’acob et al., 2018), piston engine (Khairuddin et al., 2017), industrial working conditions (Abdul Samad et al., 2022a), and educational technology (Yusof et al., 2019) – depending on the educators’ individual strengths, talents, and skills. For future research, it is hoped that adapted CLT in sports can be transgressed into other sports or group activities which require equally loaded in-game communications like basketball, football, managing events, organizing ceremonies, and online meetings.

Acknowledgments

The financial budget for this project was funded by Universiti Teknologi MARA Melaka (Geran Dalaman TEJA 2022; grant number: GDT2022/1-11).

References

Abdul Samad, A. G., Azizan, M. A., Khairuddin, M. H., & Johari, M. K. (2022a). A Review on the Mental Workload and Physical Workload for Aircraft Maintenance Personnel. Human-Centered Technology for a Better Tomorrow, 627-635. DOI:

Abdul Samad, A. G., Azizan, M. A., Khairuddin, M. H., & Johari, M. K. (2022b). Effect of Mental Workload on Heart Rate Variability and Reaction Time of Aircraft Maintenance Personnel. Human-Centered Technology for a Better Tomorrow, 613-625. DOI:

Abdul Samad, A. G., Azizan, M. A., Khairuddin, M. H., & Johari, M. K. (2022c). Significance of aircraft maintenance personnel’s reaction time during physical workload and mental workload. SpringerLink. DOI:

Adhabi, E. A. R., & Anozie, C. B. L. (2017). Literature Review for the Type of Interview in Qualitative Research. International Journal of Education, 9(3), 86. DOI:

Alsaawi, A. (2014). A critical review of qualitative interviews. Social Science Research Network. DOI:

Aprianie, E. (2005). A study on English sports terminologies written in the Jawa Pos newspaper [Master's thesis, University of Muhammadiyah Malang]. UMM Institutional Repository.

Atabek, O. (2020). Alternative certification candidates' attitudes towards using technology in education and use of social networking services: A comparison of sports sciences and foreign language graduates. World Journal on Educational Technology: Current Issues, 12(1), 1-12. DOI:

Chen, K.-M., & Hsu, K.-P. (2007). Learning English by reading sports news headlines. Journal of the Department of Physical Education, 7, 83–92.

D'Elia, F., Sgrò, F., & D'Isanto, T. (2020). The educational value of the rules in volleyball. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise - 2020 - Spring Conferences of Sports Science. DOI: 10.14198/jhse.2020.15.proc3.15

Deng, F. (2020). Book review: Marcus Callies and Magnus Levin (Eds.), Corpus approaches to the language of sports: Texts, media, modalities. Discourse Studies, 22(5), 642–643. DOI:

Fédération Internationale de Volleyball. (2022). Glossary - Volleyball Game. FIVB. https://www.fivb.com/en/volleyball/thegame_glossary

Flick, U. (2018). The SAGE handbook of qualitative data collection. SAGE Publications Ltd.

Fusion Volleyball Club. (2019). Volleyball basics. In Fusion VBC. https://dt5602vnjxv0c.cloudfront.net/portals/4951/docs/2019-2020%20season/2019-20%20fusion%20volleyball%20club%20handbook.pdf

Google Scholar. (2022, March 29). Participant observation in sports research. In Google Scholar. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=participant+observation+in+sports+research&btnG=

Khairuddin, M. H., Yahya, M. Y., & Johari, M. K. (2017). Critical needs for piston engine overhaul centre in Malaysia. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 270. DOI:

Mendes, P. C., Leandro, C. R., Campos, F., Fachada, M., Santos, A. P., & Gomes, R. (2021). Extended school time: impact on learning and teaching. European Journal of Educational Research, 10(1), 353-365. DOI:

MIT Women's Volleyball Club. (2008). Rotations, Specialization, Positions, Switching and Stacking. MIT. https://wvc.mit.edu/sites/default/files/documents/ServiceRotation_080911.pdf

Musante, K., & DeWalt, B. (2011). Participant observation: A guide for fieldworkers. AltaMira Press.

Peter, N. (2021, August 12). The rise of volleyball: From humble beginnings to a global sport. International Olympic Committee. https://olympics.com/en/news/what-history-volleyball-game-origin-mintonette-ymca-fivb-olympics

Pranoto, B. E., & Suprayogi, S. (2020). A Need Analysis of ESP for Physical Education Students in Indonesia. Premise: Journal of English Education, 9(1), 94. DOI: 10.24127/pj.v9i1.2274

Ronkainen, N. J., Aggerholm, K., Ryba, T. V., & Allen-Collinson, J. (2021). Learning in sport: from life skills to existential learning. Sport, Education and Society, 26(2), 214-227. DOI:

Taylor, S., Bogdan, R., & DeVault, M. (2015). Introduction to qualitative research methods - A guidebook and resource. John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Tomlinson, B., & Masuhara, H. (2009). Playing to Learn: A Review of Physical Games in Second Language Acquisition. Simulation & Gaming, 40(5), 645-668. DOI: 10.1177/1046878109339969

UiTM Melaka. (2022). UiTM Melaka - Admission Now. In UiTM Melaka. https://melaka.uitm.edu.my/index.php/en/admission-now

Williams, M., & Moser, T. (2019). The art of coding and thematic exploration in qualitative research. International Management Review, 15(1), 45–55.

Ya’acob, A. M., Razali, D. A., Anwar, U. A., Radhi, A. H., Ishak, A. A., Minhat, M., Mohd Aris, K. D., Johari, M. K., & Casey, T. (2018). Preliminary Study on GF/Carbon/Epoxy Composite Permeability in Designing Close Compartment Processing. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 370, 012030. DOI:

Yusof, M. A., Ya’acob, A. M., Mohd Zaki, M. A., Abdul Rahman, Z., Zainol Abidin, N. H., Padil, I. F., Johari, M. K., Bakar, I. A., & Mohd Hashim, H. F. (2019). Developing a virtual reality (VR) app for theory of flight & control as a teaching & learning aid. International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering, 8(6S), 670–673.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 September 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-964-1

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

7

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-929

Subjects

Language, education, literature, linguistics

Cite this article as:

Johari, M. K., & Jamil, N. Z. (2023). Learning & Improving English Communication With Volleyball - A Qualitative Study. In M. Rahim, A. A. Ab Aziz, I. Saja @ Mearaj, N. A. Kamarudin, O. L. Chong, N. Zaini, A. Bidin, N. Mohamad Ayob, Z. Mohd Sulaiman, Y. S. Chan, & N. H. M. Saad (Eds.), Embracing Change: Emancipating the Landscape of Research in Linguistic, Language and Literature, vol 7. European Proceedings of Educational Sciences (pp. 783-795). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.23097.70