Abstract

In higher education institutions today, the use of technology among learners studying a second or foreign language is abundant, especially when it comes to the use of machine translation. This study aims to gauge language instructors' perception at higher education institutions on the (1) use of machine translation in learning a language and the (2) extent of its use by second or foreign language learners in completing writing tasks and assessments. Following Benson model for autonomous learning, a set of questionnaires was developed which emphasises on three levels which are technology-based approach, teacher-based approach, and resource-based approach. Data was collected from 127 English, Mandarin, Japanese and Arabic language instructors from various higher educational institutions via online questionnaires. Data analysis was conducted using PASW Statistics software (SPSS) version 28 for descriptive statistics. The findings demonstrate that a significant portion of second or foreign language instructors in Malaysia (1) believe that machine translation is useful as an auxiliary tool for learners in second or foreign language writing; (2) opine that the use of machine translation increases learners’ confidence in their language writing; (3) agree that language translation machines mostly were used for sentence translation in language writing, followed by paragraph translation and checking vocabulary in language writing; (4) are able to detect their learners using machine translation as an auxiliary tool in their language writing tasks or assessments; and (5) are hesitant on the idea of allowing and consenting their students using translation machine in completing language assessments.

Keywords: Higher education, language instructors, machine translation, second or foreign language learners

Introduction

The Malaysian Education Blueprint 2015–2025 states that the government urges students to study global languages to meet the demands of the vastly-growth market. As a result, various foreign language courses are currently being gradually offered at both primary and secondary schools. In the era of artificial intelligence, a high talent demand of the society requires for a learning process that incorporates human and machine (Ahmad, 2019). Presently, there is a new trend observed in the process of second or foreign language learning, whereby the inclination to use technology among learners at higher education is increasing rapidly, especially in machine translation (Clifford et al., 2013; O’Neill, 2019a). According to research, when learning a foreign language, learners tend to use machine translation abundantly. When it comes to translating word, sentence or even paragraph, machine translation is the primary source of assistance among learners (Fibriana et al., 2021). Its use is even more widespread in second or foreign language learning. Research also shows that one of the most used language learning applications among tertiary-level students in Malaysia is in fact machine translation (Chan & Ang, 2017). Thus, it is undeniable that in completing course writing and assessments, learners tend to opt for machine translation. This preference, however, poses another challenge to learners as they lack the knowledge to use machine translation effectively, and therefore requires close guidance from instructors.

This situation leads to the emergence of new learning atmosphere as teaching and assessment methods are impacted, apart from learners’ styles of learning. Nevertheless, little is known about how instructors perceive machine translation as an auxiliary tool for second or foreign language learners. What is the instructors’ perception towards the use of machine translation in the process of learning and assessing second and foreign languages? To date, machine translation has not been included as part of any content in language learning at tertiary level in Malaysia. Despite its vast usage among language learners, the acceptance of instructors towards machine translation remains unclear. Do instructors support the use of machine translation in language learning? If yes, to what extent are they willing to allow its usage?

It is undeniable that machine translation offers translation services to learners in the most convenient way possible, especially in this fast-paced era where the value of time is increasing (Motlaq & Mahadi, 2020). However, some believe that despite the benefits it provides, machine translation is insufficient, without the inclusion of human correction. Translating, modifying, and polishing words and sentences remain as one of the most necessary skills acquired by language learners. Thus, it is significant to acknowledge the widespread use of machine translation, without disregarding the importance of manual editing. The incorporation of machine translation into language classroom is therefore seen as one of the most effective pedagogical approaches to assist learners to use it efficiently (Motlaq & Mahadi, 2020).

Moreover, the level of academic dishonesty and plagiarism has heightened rapidly over the past few years, more so with the introduction of machine translation in various fields of study (Mundt & Groves, 2016). Due to the concern towards current education policy, the awareness on the issues of academic misconduct and plagiarism is increasing, with academicians actively participating in discussion and research on overcoming this obstacle (Mundt & Groves, 2016). As such, this study encompasses academic writing as the scope of this study. Based on the widespread use of machine translation, it is of utmost importance to find out whether instructors acknowledge the benefits offered by machine translation, and whether they accept its use in language learning at tertiary level. If yes, to what extent do they think it is being used by learners. It is hoped that despite the boundaries posed by the different languages, the use of machine translation is able to assist learners faster and easier, by diminishing learners’ total reliance on it, so that effective communication and language skills will be achieved through the improvement of learners’ second or foreign language.

Literature review

Structure Instructors’ beliefs regarding the use of machine translation

Numerous studies have looked into how second or foreign language students perceive the use of machine translation, but only a small number of studies have looked into how second or foreign language instructors perceive the use of machine translation. Previous research found that proper training on effective use of machine translation is deemed as necessary from both instructors’ and learners’ perspectives (Jolley & Maimone, 2015). This notion is supported by Bowker (2020) who proposed the idea of literacy training for machine translation to empower its use collaboratively. Few studies have investigated the use of machine translation from the instructors’ perspectives. Rico and González Pastor (2022) investigated professional translation instructors’ beliefs and perspective towards the use of machine translation in the classroom but fails to incorporate the general language instructors’ opinions on learners’ use of machine translation.

Similarly, studies on instructors’ perspectives on the use of machine translation in Malaysia is scarce, even though the use of Google Translate is widespread among Malaysian tertiary students (Chan & Ang, 2017). Eriksson (2021) explored instructors’ beliefs and practices regarding the use of free online machine translation tools and found that instructors strongly recommend their students to limit the use of the tools only to their personal lives, and use other sources for learning purposes instead. Ata and Debreli (2021) investigated both learners’ and instructors’ perceptions towards online machine translation in foreign language classrooms. The results show that instructors tend to overestimate the use of online machine translation among learners, while learners, on the other hand, undervalues instructors’ acceptance in online machine translation. Likewise, Liu et al. (2022) conducted a study on the perception and attitudes of translation instructors and learners. The results show that 60% of instructors strongly agreed or agreed that they encouraged the use of machine translation in translation teaching with clear ethical policies. Niño (2009) similarly, investigated the attitudes of learners and language instructors towards machine translation in foreign language classroom at higher learning institution. It was interesting to find that although both learners and instructors believe that the use of machine translation leads to a positive and innovative learning experience, only a few instructors used machine translation as an auxiliary tool. Thus, considering the perspectives of both learners and instructors is vital in order to understand the complexity of the use of machine translation in second or foreign language teaching.

Nevertheless, despite numerous evidence that instructors are still doubtful towards the use of machine translation, latest studies show that instructors are gradually opening up to the idea of using machine translation in language learning. Ata and Debreli (2021) found that compared to learners, instructors exhibit a higher level of positivity towards the effectiveness of machine translation. In addition, Cancino and Panes (2021) also conducted a similar study and found that instructors did not reject the use of machine translation in total, but rather admitted the potential it has in language enhancement. Findings by Stapleton and Leong (2019) also show that instructors frequently make allowances for learners to use machine translation in spite of numerous perceived flaws of its output, especially when using platforms such as Google Translate and online dictionaries. It is interesting to note that most instructors fail to detect learners’ use of machine translation due to the increasing accuracy of machine translation output (Stapleton & Leong, 2019).

Guidelines for effective use of machine translation

Previous research have recommended for effective use of machine translation by encouraging instructors to provide guidance to learners instead of prohibiting them from using it (Cancino & Panes, 2021; Wei, 2021; Yoon, 2016). A set of guidelines can be formed for instructors in assisting learners to use machine translation for effective learning. Firstly, instructors ought to clarify to learners the pros and cons of machine translation and the method to use it effectively as auxiliary tools (Lee, 2020). Second, instructors need to highlight factors that may jeopardise the output quality of machine translation by demonstrating to learners of the numerous effective and ineffective applications and methods to utilise machine translation (e.g. form of text, task or purpose, assignment, and the intricacy and length of each part etc.) (Jolley & Maimone, 2015; O’Neill, 2019b; Stapleton & Leong, 2019). Third, instructors have to explain the effects and rules of using machine translation to learners (e.g. learners need to fully comprehend which types of tasks allow the use of machine translation tools) (Jolley & Maimone, 2015). Finally, instructors are encouraged to assist learners in developing the necessary skills to properly use machine translation such as editing, instead of taking in the output in total (Case, 2015; O’Neill, 2019a).

The incorporation of machine translation into language learning has also been heavily emphasised. Instructors need to acknowledge the benefits of machine translation and subsequently utilise it as an auxiliary tool in language learning (Ducar & Schocket, 2018). Machine translation ought to be included in the instructional pedagogy in order to empower learners to extend its use beyond the walls of the classroom (Wei, 2021). In addition, the incorporation of machine translation into language learning will serve as an eye-opener for learners to expose themselves to the various media and tools available (McDougall et al., 2018). Therefore, it is vital for language instructors to possess a certain level of flexibility and adaptability in modifying their teaching strategies in order to utilise technology to its full potential (Golonka et al., 2014; Pérez Cañado, 2018).

Research Question

What are university language instructors’ beliefs regarding the use of machine translation among learners in completing second or foreign language writing tasks and assessments?

Research Objective

To explore the beliefs of university language instructor regarding learners' use of machine translation in completing second or foreign language writing tasks and assessments.

Research Methods

This study uses quantitative method, which is an online survey with 5-point Likert Scale. A group of 127 instructors teaching second or foreign languages at tertiary level in Malaysia were chosen as the respondents in the study. The respondents’ details are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 shows the frequency of the respondents' profiles. From the sample, respondents between the age of 31-40 years formed the largest age group (35.4%), followed by the age of 41-50 (32.3%), 51-60 years (28.3%) and below 31 years (3.9%). This study encompasses 72.4% female and 27.6% male respondents. 31.5% of the respondents teach English, 26.8% teach Mandarin, 23.6% teach Japanese and 18.1% teach Arabic. With regards to teaching experience, 38.6% of the respondents have more than 20 years of teaching experience followed by 4-10 years (25.2%), 11-15 years (24.4%) and 16-20 years (11.8%).

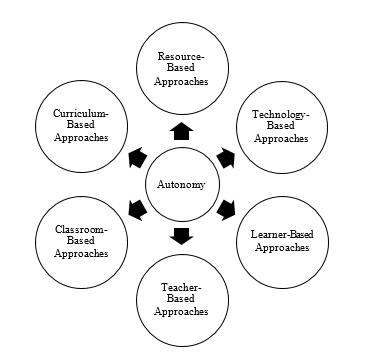

Figure 1 shows Benson’s (2011) model for the promotion of autonomous learning in the class. As illustrated in this model, there are various levels that support learners autonomy, which are (1) resource-based approach that emphasises on using learning resources independently; (2) curriculum-based approach which emphasises on curriculum control; (3) classroom-based approach that concentrates on classroom control decisions; (4) teacher-based approach emphasising teacher roles; (5) learner-based approach that inculcates autonomous learning skills growth and (6) technology-based approach which promotes the use of learning technologies independently.

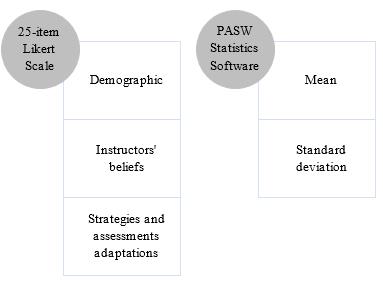

Based on Benson’s model, a set of questionnaires was developed by the researchers as the instrument of the study. In this study, three levels were selected to guide the construction, which are technology-based approach, learner-based approach, and resource-based approach. Bearing Benson’s (2011) model in mind, it is crucial to acknowledge the importance of using and interacting with learning technologies to promote learners autonomy in which the language instructors’ roles are to facilitate and support learners in exploring and encouraging the use of digital literacy. Respondents were requested to fill out the 25-item Likert scale instrument. Figure 2 shows further details of the questionnaires and the tool used to analyse the data in the questionnaires.

The questionnaires consist of three parts; the aim of the first part is to elicit respondents’ demographic details; the second part (Item 1-13) is aimed to find out the beliefs of instructors regarding the use of machine translation among learners in completing second or foreign language tasks and assessments. Meanwhile, part three (Item 14-25) of the questionnaire was formulated to explore instructors’ adaptations in terms of teaching strategies and assessments within the context of machine translation. All the 127 questionnaires were returned completely, signifying a return rate of 100% from the participants. The level of agreement of the instructors was elicited from each statement via a 5-point scale (1=Strongly agree, 2=Agree, 3=Neutral, 4=Disagree, 5=Strongly disagree). A higher score suggests a more positive attitude towards the item(s) while a lower score indicates a more negative attitude. The data analysis was conducted using PASW Statistics software (SPSS) version 28 for descriptive statistics. The results indicate reliable level (0.896), which is greater than 0.7, based on Cronbach’s alpha reliability score. In determining the beliefs and perceptions of instructors regarding the use of machine translation among learners, mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) were calculated using statistical analysis which was conducted based on the research questions. The average score of each response to each case (range 1-5) was reported using the measurement method proposed by Hanson et al. (2005) This method suggests that an average score of 1.00 to 2.33 is considered low, an average score of 2.34 to 3.67 is medium, and an average score of 3.68 to 5.00 is high.

Findings

5-point Likert Scale was used in the survey, minimum point was 1 and the maximum point was 5.

Table 2 shows the perceptions of language instructors in using machine translation for language learning. There were 127 language instructors involved in the research, and the four languages involved in the research were English, Arabic, Japanese and Mandarin. Based on their responses, all the language instructors agreed that machine translation is useful as an auxiliary tool for learners in second or foreign language writing, 3.71. Among the four languages, Arabic language instructors agreed the most (3.91) that machine translation is useful for learners in second or foreign language writing, followed by Japanese language instructors (3.83), English language instructors (3.72) and Mandarin language instructors (3.44).

Language instructors do not often use machine translation as an auxiliary tool in their language instruction (2.38) and do not include hands-on practice on machine translation as an auxiliary tool in their class (2.13). English language instructors seldom use machine translation in language instruction (2.00) and rarely include hands-on practice on machine translation in their class (2.05), as they believe that students are already familiar with various types of machine translation, and it is not necessary to teach that purposely in class.

Mandarin language instructors also rarely use machine translation as an auxiliary tool as part of their language instruction (2.03) and seldom include hands-on practice on machine translation as an auxiliary tool in their class (1.85). Similar to Mandarin language instructors, Japanese language instructors (2.00) also seldom include hands-on practice on machine translation as an auxiliary tool in their class, and this happened mainly because of the time factor.

Table 3 describes the perceptions of language instructor in learners using machine translation in learning second or foreign language. Based on the results, language instructors agreed that majority of their learners use machine translation as an auxiliary tool in their second or foreign language writing tasks, 3.75. The Arabic language instructors felt that most of their students used machine translation (4.09) and other languages have not much difference, English (3.69), Mandarin (3.68) and Japanese (3.67).

Arabic (3.78), English (3.48) and Japanese (3.40) language instructors accepted the use of machine translation among their learners as an auxiliary tool to complete second or foreign language writing tasks. However, Mandarin language instructors (2.88) were not so keen on the idea of allowing their learners to use it, and they cited the factor of the inefficiency of Mandarin machine translation as compared to other languages as one of the reasons.

Table 4 illustrates the perceptions of language instructor in using machine translation for which purpose in learning second or foreign language. According to the language instructors, language machine translation mostly were used for sentence translation in language writing (3.99), followed by paragraph translation (3.68) and checking vocabulary in language writing (3.53). Perception of all the languages instructors were the same.

Table 5 depicts the perceptions of language instructor in reliance and confidence on machine translation for learning second or foreign language. Regarding the students’ level of confidence while using machine translation in language writing, all the language instructors agreed that their students will feel confident when using machine translation in their language writing (3.64).

In terms of the students’ reliability on machine translation in language writing, language instructors feel that their students will rely on machine translation for language writing (2.65), due to this question being a negative statement. However, Japanese language instructors do not share the same opinion (3.67).

Table 6 shows the perceptions of language instructor in students using machine translation for assessment of second or foreign language. Based on the responses, most of the language instructors think that majority of their learners use machine translation as an auxiliary tool in their second or foreign language assessment (3.57) and the value is not so much different among the languages: Arabic (3.96), English (3.56), Mandarin (3.47) and Japanese (3.40).

Mandarin (2.56) and Japanese (2.83) language instructors do not agree that learners can use machine translation as an auxiliary tool to complete their second or foreign language assessments, and this is in contrast with Arabic (3.48) and English (3.13) languages instructors’ perception.

Table 7 demonstrates the perceptions of language instructors’ ability to detect learners using machine translation for writing task in second or foreign language. According to their responses, majority of the language instructors are able to detect their learners using machine translation as an auxiliary tool in their language writing tasks (4.28). The results shown are almost similar across all four languages, with Japanese (4.50), Arabic (4.48), Mandarin (4.36) and English (3.95).

Table 8 presents the perceptions of language instructors’ consent in learners using machine translation for writing task in second or foreign language. The results show that majority of the language instructors are able to detect their learners using machine translation as an auxiliary tool in their language assessments (4.20), especially foreign language instructors: Arabic (4.48), Japanese (4.33) and Mandarin (4.26). English language instructors (3.88) are less sensitive compared to foreign language instructors. This is because in some English courses, students are allowed to use dictionary.

Table 9 shows the perceptions of language instructors in allowing and giving consent to the learners using machine translation in completing language writing. The findings indicate that Mandarin language instructors do not completely agree in letting their learners use machine translation as an auxiliary tool in their language writing (2.61) compared to other language instructors: Arabic (3.35), Japanese (3.10) and English (3.00). This is mainly because they feel that Mandarin online machine translation is not reliable compared to other languages.

Table 10 depicts the perceptions of language instructors in allowing and consenting the students to use translation machine in completing language assessments. It was found that majority of the language instructors are not welcome to the idea of allowing and consenting their students to use machine translation in completing language assessments (2.49), especially Mandarin language instructors (2.03), English (2.53) and Japanese (2.57). Arabic language instructors (3.00) on the other hand were not so opposing to the idea of allowing their students to use machine translation in completing language assessments.

Conclusion

All the language instructors agreed that machine translation is useful as an auxiliary tool for learners in second or foreign language writing. However, language instructors do not often use machine translation as an auxiliary tool in their language instruction, including hands-on practices in class.

Language instructors also agreed that majority of their learners use machine translation as an auxiliary tool in their second or foreign language writing tasks, and that their students will feel confident when they use machine translation in their language writing.

Perception of all the languages instructors were the same; they believe that language translation machines mostly were used for sentence translation in language writing, followed by paragraph translation and checking vocabulary in language writing.

Most of the language instructors think that majority of their learners use machine translation as an auxiliary tool in their second or foreign language assessment, and they are able to detect their learners using machine translation as an auxiliary tool in their language writing tasks or assessments.

Majority of the language instructors are not welcoming to the idea of allowing and consenting their students using machine translation in completing language assessments, except for language writing. Language instructors also do not encourage learners to use machine translation, which can be drawn from the fact that they do not often use machine translation in teaching and do not teach learners to use it in classrooms.

Among the language instructors teaching the four languages, Mandarin language instructors have the most negative views on the use of machine translation by learners, while Arabic language instructors are most optimistic that machine translation can help students learn. The views of English and Japanese language instructors are in the middle between those of Mandarin and Arabic language instructors.

The use of machine translation in foreign language learning could be advantageous. Therefore, we propose that machine translation be integrated into the foreign language curriculum, and specific training for instructors and learners according to their actual use and needs be provided. Foreign language instructors could guide learners to use machine translation for learning, and utilize machine translation as an autonomous, diverse, and open approach to foreign language acquisition.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Geran Penyelidikan MYRA, Universiti Teknologi MARA [600-RMC/GPM LPHD 5/3 (122/2021)]. Special thanks to Universiti Teknologi MARA, Cawangan Pulau Pinang and Cawangan Perlis for the facilities.

References

Ahmad, T. (2019). Scenario based approach to re-imagining future of higher education which prepares students for the future of work. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 10(1), 217–238.

Ata, M., & Debreli, E. (2021). Machine translation in the language classroom: Turkish EFL learners’ and instructors’ perceptions and use. IAFOR Journal of Education, 9(4), 103–122.

Benson, P. (2011). Language learning and teaching beyond the classroom: An introduction to the field. In: Benson, P., & Reinders, H. (Eds.), Beyond the Language Classroom (pp. 7-16). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Bowker, L. (2020). Machine translation literacy instruction for international business students and business English instructors. Journal of Business and Finance Librarianship, 25(1–2), 25–43.

Cancino, M., & Panes, J. (2021). The impact of Google Translate on L2 writing quality measures: Evidence from Chilean EFL high school learners. System, 98, 102464.

Case, M. (2015). Machine translation and the disruption of foreign language learning activities. ELearning Papers, 45, 4–16. http://du.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A874792&dswid=8504

Chan, N. N., & Ang, C.-S. (2017). Investigating the use of mobile applications in everyday language learning. International Journal of Mobile Learning and Organisation, 11(4), 378–394.

Clifford, J., Merschel, L., & Munné, J. (2013). Surveying the landscape: What is the role of machine translation in language learning? @ Tic. Revista d’innovació Educativa, 10, 108–121. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3495/349532398012.pdf

Ducar, C., & Schocket, D. H. (2018). Machine translation and the L2 classroom: Pedagogical solutions for making peace with Google Translate. Foreign Language Annals, 51(4), 779–795.

Eriksson, N. L. (2021). Google Translate in English-language learning: A study of teachers’ beliefs and practices [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Dalarna University.

Fibriana, I., Ardini, S. N., & Affini, L. N. (2021). Google Translate and its role in academic writing for university students. Journal of Advanced English Studies, 4(1), 26–33. https://jaes.journal.unifa.ac.id/index.php/jes/article/view/96

Golonka, E. M., Bowles, A. R., Frank, V. M., Richardson, D. L., & Freynik, S. (2014). Technologies for foreign language learning: A review of technology types and their effectiveness. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 27(1), 70–105.

Hanson, W. E., Creswell, J. W., Clark, V. L. P., Petska, K. S., & Creswell, J. D. (2005). Mixed methods research designs in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 224.

Jolley, J. R., & Maimone, L. (2015). Free online machine translation: Use and perceptions by Spanish students and instructors. Learn Languages, Explore Cultures, Transform Lives, 181–200.

Lee, S. M. (2020). The impact of using machine translation on EFL students’ writing. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 33(3), 157–175.

Liu, K., Kwok, H. L., Liu, J., & Cheung, A. K. F. (2022). Sustainability and influence of machine translation: Perceptions and attitudes of translation instructors and learners in Hong Kong. Sustainability, 14(11), 6399. MDPI AG.

McDougall, J., Readman, M., & Wilkinson, P. (2018). The uses of (digital) literacy. Learning, Media and Technology, 43(3), 263–279.

Motlaq, M. D. A., & Mahadi, T. S. T. (2020). Advantages and disadvantages of using machine translation in translation pedagogy from the perspective of instructors and learners. Humanities & Social Sciences Reviews, 8(4), 121–137.

Mundt, K., & Groves, M. (2016). A double-edged sword: The merits and the policy implications of Google Translate in higher education. European Journal of Higher Education, 6(4), 387–401.

Niño, A. (2009). Machine translation in foreign language learning: Language learners’ and tutors’ perceptions of its advantages and disadvantages. ReCALL, 21(2), 241–258.

O’Neill, E. M. (2019a). Online translator, dictionary, and search engine use among L2 students. Call-EJ, 20(1), 154–177. http://callej.org/journal/20-1/O’Neill2019.pdf

O’Neill, E. M. (2019b). Training students to use online translators and dictionaries: The impact on second language writing scores. International Journal of Research Studies in Language Learning, 8(2), 47-65.

Pérez Cañado, M. L. (2018). Technology for teaching English as a foreign language (EFL) Writing. The TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching, 1–12.

Rico, C., & González Pastor, D. (2022). The role of machine translation in translation education: A thematic analysis of translator educators’ beliefs. Translation and Interpreting, 14(1), 177–197.

Stapleton, P., & Leong, K. K. (2019). Assessing the accuracy and teachers’ impressions of Google Translate: A study of primary L2 writers in Hong Kong. English for Specific Purposes, 56(July), 18–34.

Wei, L. K. (2021). The use of Google Translate in English language learning: How students view it. International Journal of Advanced Research in Education and Society, 3(1), 47–53.

Yoon, C. (2016). Concordancers and dictionaries as problem-solving tools for ESL academic writing. Language Learning & Technology, 20(1), 209–229.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 September 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-964-1

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

7

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-929

Subjects

Language, education, literature, linguistics

Cite this article as:

Hamid, H. A., Terng, H. F., Ling, L. Y., & Kaur, N. (2023). Instructors’ Perception of Using Machine Translation In Second Language Learning and Assessment. In M. Rahim, A. A. Ab Aziz, I. Saja @ Mearaj, N. A. Kamarudin, O. L. Chong, N. Zaini, A. Bidin, N. Mohamad Ayob, Z. Mohd Sulaiman, Y. S. Chan, & N. H. M. Saad (Eds.), Embracing Change: Emancipating the Landscape of Research in Linguistic, Language and Literature, vol 7. European Proceedings of Educational Sciences (pp. 58-71). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.23097.6