Abstract

Previous studies on the adaptation of Reader’s Theatre in English language learning and Literature classrooms have suggested that not only it can improve reading comprehension, also it is deemed to be a motivating, interactive and entertaining approach, especially for reluctant language learners. Learning of literature helps learners to recognise semiotic representation, ambiguity, and ambivalent voices which they can translate their interpretation of these different elements into a performance-based assessment. Studies have proven that Reader’s Theatre can be adapted as an alternative assessment tool to measure students’ learning performance. Alternative assessment is argued to be a better option to traditional assessment for it is more realistic and facilitates higher order thinking. This study examines on the use of Online Reader’s Theatre (ORT) as an alternative assessment tool in a literature class. The findings from the quantitative data showed that ORT not only has helped students to sustain their interest in learning literature and increase their engagement with their peers and instructors, also, they found ORT to be effective and holistic in measuring their knowledge and understanding of the play compared to traditional written form assessment. Living in a complex, uncertain and precarious post pandemic world has brought critical impact to the overall landscape of assessment which requires instructors to re-design their course delivery and assessment modes to make it more relatable, flexible and meaningful for learners.

Keywords: Alternative assessment, Higher Education, online Reader’s Theatre (ORT), teaching and learning literature

Introduction

The richness and complexities of literary text may cause learners to find learning literature to be challenging yet stimulating. The younger generation may also opine that learning literature is tedious and outdated. Despite such challenges, it is essential to integrate literature into language learning as it may help to enrich the learning experience of not only learning a language but also recognising the people and culture associated to the language (Bakar, 2021).

Assessment is critical in creating “backwash effect” which is defined as the manner students’ learning can be altered through assessment design (Prodromou, 1995; Watkins et al., 2005). In other words, preparing for assessment gives the drive on the manner students learn which may lead to the improvement of quality of their learning accomplishment (Edström, 2008; Vu & Dall’Alba, 2014). However, conventional assessment is said to only be able to measure decontextualized lower order thinking (Villarroel et al., 2020). It focuses on knowledge reproduction that requires students to memorise the information and reproduce them mechanically within a closed-setting with invigilators at present. This brings adverse effect to the students as they become passive learners (Schell & Porter, 2018; Villarroel et al., 2020). The pandemic has disrupted learning and hastily brings higher education into the era of uncertainty and precarity. Not only instructors need to adapt to pedagogical techniques related to online learning to help students to better attain the learning outcomes, they also need to reconsider the way they conduct their assessments (Hatzipanagos et al., 2020). Conventional assessments like sitting for physical examinations were perceived to be unsuitable, ergo instructors need to develop and design alternative assessments which can be executed online. Digital tools are adopted and integrated as part of the platforms to carry out online assessment. This abrupt transition to online assessment imposes several challenges like the quality of the assessment and whether online assessment can measure students’ performance objectively (Guangul et al., 2020). During crises, to assess students using conventional methods may pose a challenge, thus, alternative assessments like self-reflections or portfolios are recommended. Pre-defined and well-prepared alternative assessment approaches provide affordances for students to take charge for their own learning, while concurrently improved motivation, academic engagement and metacognition (Kearney & Perkins, 2014; Nicol et al., 2014; Rapanta et al., 2020; Vanaki & Memarian, 2009). In addition, curriculum design at higher education has also been designed to be more futuristic and flexible, thus it is instrumental for all instructors to refashion conventional assessment as a means to prepare for future learning process.

Learning does not merely equate with gaining knowledge, instead interior qualities like skills and attitudes are more crucial (Abd Rahim, 2021). This may be achieved through the use of Reader’s Theatre. Initially, Reader’s Theatre may be presumed to only be relevant for language learning, in particular in the learning of literature. On the contrary, Reader’s Theatre has been a useful pedagogical tool in other discipline like nursing and law. Reader’s Theatre is claimed to provide students with the experience of immersing themselves into the real world (MacRae & Pardue, 2007) apart from improving understanding on the course content, promoting peer-interaction and developing critical thinking skills among students (Cross, 2017; Khanlou et al., 2022; Rasisnski et al., 2017). When applied in a literature classroom, Reader’s Theatre may be used to enhance the study of language, to encourage exploration of different point of view, to facilitate the acquisition of language skills and as an outlet for students to display their creativity by participating in theatrical performance as a means to deliver their interpretation of a literary text (Ratliff, 2000). The elements of performance and drama embedded in Reader’s Theatre can help to develop emotional and intellectual capabilities and nurture collaborative learning through teamwork (Kalamees-Ruubel & Läänemets, 2012). For the purpose of this research, Reader’s Theatre is re-fashioned in a language and literature class for higher education by redefining its conventional principles of oral presentation and recitative reading and transforms it into an alternative assessment approach. To date, there are limited studies that focuses on using ORT as an alternative assessment to measure students’ comprehension and analysis of a literary text. Thus, this study is designed by uplifting conventional reader’s theatre models using digital platforms during disrupted setting and examined students’ perception on its usage as an alternative assessment tool.

Literature review

Reader’s Theatre As A Pedagogy For English Language Teaching

Conventionally, Reader’s Theatre is an instructional activity that is used to improve learners’ reading fluency via the component of literature in an ESL class (Corcoran & Davis, 2005; Uribe, 2019a Worthy & Prater, 2002; Young & Rasinski, 2018). Bloom et al. (2009) asserted that Reader’s Theatre is “a powerful strategy” to engage students at higher education by affording them with opportunities to interact, to rehearse and perform scripts for an audience (Worthy & Prater, 2002; Young et al., 2019). Moreover, it is also argued to be easily adaptable and helps to facilitate the process of connecting to the literary texts (Young & Rasinski, 2018; Zimmerman et al., 2019).

Initially, Reader’s Theatre is defined as “an interpretive, voice-only performance” (Vasinda & McLeod, 2011, p. 487) which requires no additional props, costumes or even acting. This is because Reader’s Theatre mainly gives focus on expressive and meaningful reading performance of a literary text to an audience (Worthy & Prater, 2002; Young et al., 2019). Flynn (2007) further describes the approach of Reader’s Theatre as an instructional design that imbues basic performance element through dramatisation with subject matter. Many studies on Reader’s Theatre have asserted the benefits in improving students’ language skills, language competence, cultural awareness, reading comprehension, information retention, communication skills, and comprehension (Drew & Pedersen, 2010; Liu, 2000; Ng, 2008; Nugent, 2021; Uribe, 2019b). Apart from contributing positively to the development of language skills, Reader’s Theatre is remarked to be motivating and cultivating collaborative skills with their peers (Ng, 2008; Nugent, 2021). Reader’s Theatre is also considered to be a “low anxiety activity” that is weaved between educational values and entertainment (Lo et al., 2021, p. 3).

With time, Reader’s Theatre is re-fashioned by integrating the elements of drama and performance. To bring the vision to action, the reader needs to portray the emotions, goals and motives of the character that he is performing by engaging in “deeper analytical thought” in order to extent the plot of the story to the audience (Guzzetti, 2002; Vasinda & McLeod, 2011). Participants of Reader’s Theatre become interwoven with images, characters, and backdrop presented in the dramatization which “arouses emotion” within the viewers as they are engulfed by the depicted conflicts on stage (MacRae & Pardue, 2007, p. 533).

To adapt to the demands of sudden changes to the educational landscape due to the pandemic, the facets of Reader’s Theatre is further expanded by integrating it into online learning environments. The pandemic has triggered for the shift from conventional to online learning, thus integrating learning with the use of technology is perceived essential. ORT is categorized as a performance-based assessment which provides allowances for students to demonstrate the attained learning outcomes and to apply knowledge and skills within a purposeful learning context (Haertel, 1992; Reeves, 2000). Such changes are parallel with the sudden transformation of educational landscape post-pandemic.

Opportunities of Alternative Assessment

Assessment is commonly referred to as a method to inform instructors on the achievement of the learning outcomes by students (Angelo & Cross, 2012). This definition is further broadened to which both formative and summative assessment is used with the former to construct knowledge while the later to determine the “depth and breadth of knowledge” attain by students (van Vuuren, 2022, p. 163). The pandemic has pivoted higher education institutions to rapidly innovate conventional educational practices. This transformation is inevitable as the entire education landscape changed overnight. Technology quickly becomes the reliable tool in teaching and learning including assessment during the pandemic. Technological-based assessment quickly replaced conventional assessment, however, the principles of conducting assessment remains as proposed by Rahim (2020) who asserted that apart from ensuring the validity and reliability, assessment should be aligned with the learning outcomes, be inclusive of students’ varied situations, and provide high-impact feedback. In addition, it is also necessary to ensure assessment practices are authentic and cognitively appropriate (Maistry, 2022).

Higher education traditional assessments focus on knowledge retention within limited contexts that are measured through approach such as academic writing assignments (Reeves, 2000). Conventional assessment policies and practices have been criticised to be misaligned to curriculum designs, to place too much emphasis on grading which many students found to be demotivating and affect learning aspirations (Attwood & Radnofsky, 2007; Nasab, 2015; Timmis et al., 2016). Higher education institutions need to play a significant role to prepare students to be employment-ready for the industry. Thus, an urgent call is made to reshape assessment practices that are not only able to link theory into practice, but also able to cultivate “deep approach to learning” through knowledge construction, participation in problem-solving tasks, effective collaboration and managing feedback (Adams et al., 2022). Alternative assessment inspires students to use the knowledge that they have attained in “complex and realistic contexts” (Reeves, 2000, p. 101). One of the means to achieve this is through observation of authentic or alternative assessment principles (Biggs & Tang, 2011; Timmis et al., 2016) in which students are encouraged to correspond and relate between what they have learned to what they need to perform in real life (Neely & Tucker, 2012). Alternative assessment is argued to be able to inform and monitor instructions based on students’ assessment results (Tsagari, 2004). The attainment of learning outcomes can be facilitated through the process of modifications. In addition, alternative assessment focuses on “constructivist learning”, cultivation of learning skills rather than testing which is more realistic and meaningful (Atifnigar et al., 2020; Janisch et al., 2007). It also provides affordances for students to reflect on their learning processes which leads them to improve their motivations and attitudes towards learning as well as their self-esteem (Renandya & Widodo, 2016). The strength and opportunities afforded by alternative assessment further highlight its potential in reversing “the traditional paradigm of student passivity” (Janisch et al., 2007, p. 227) into producing students with initiatives, self-discipline and choice when they are given the autonomy to direct and regulate their learning through authentic and dynamic assessment.

Research Methods

This study is primarily guided by the tenets of action research by McNiff and Whitehead (2002). Action research begins with a review process by the instructors of the current practice followed by identification of any aspects that need improvement. A way forward remedy needs to be adopted and tried out to improve the current educational practices. The outcome of the remedy is observed and evaluated for its value and the steps are repeated until the instructors feel satisfied with the outcome of the measures taken. To reflect on the pedagogical approach of ORT, this study has adapted a questionnaire adopted from Kabilan and Kamarudin (2010) which was distributed to the first-year students from Languages and Cross-cultural communication programme at Universiti Pertahanan Nasional Malaysia who took up the subject Language and Literature as an elective course in their second semester. The participants were made up of 15 male and 20 female students which range between the ages of 18 to 22 years old. At the time of this research, classes were still conducted fully online. Swordfish and The Concubine written by a Malaysian playwright, Kee Thuan Chye was studied as the material for staging of the Online Reader’s Theatre. The play is an interpretation of two tales from Sejarah Melayu; Hikayat Demang Lebar Daun and Hikayat Singapura dilanggar Todak that has been creatively re-visioned by the playwright. The play deals with issues related to history manipulation, power abuse, differentiated gender representations, treason and deconstruction of the Malay monarchy. Modern elements like rap and hip hop music are integrated into the play as signifiers that break the conventional rules of a drama. The process of designing and contextualising the alternative assessment is based on Jasper and Rosser (2013) ERA cycle (experience, reflect, action) and Brown and Hudson (1998)’s characteristics of alternative assessment. The experience of surviving the pandemic requires instructors to reflect their pedagogical practices and take the necessary action to adapt to the urgent educational needs triggered by the pandemic (see Figure 1). ORT is a performance-based assessment which requires students to create, produce and perform a dramatization of the chosen literary text which taps into their higher-level thinking and problem-solving skill.

Table 1 below illustrated the steps involved in designing ORT for the chosen literary play as an alternative assessment tool;

The study ran for four weeks from the preparatory phase to the assessment phase. By the end of the fourth week, a questionnaire was given to the students for them to ruminate on their experience while preparing and performing the ORT. The questionnaire consists of three parts; demography profiling, students’ perception on the use of ORT as learning activities, students’ perception on the use of ORT as an alternative assessment. In the second part of the questionnaire, the students were required to rate their responses according to Likert scales; 1 for Strongly Disagree to 5 for Strongly Agree. The final part of the questionnaire investigated the students’ perception on the use of ORT as an alternative assessment in a form of open-ended questions. Findings for Part I and Part II from the questionnaire were tabulated using SPSS version 23, whilst findings for Part III were analysed using principles of Reflexive Thematic Analysis as proposed by Braun and Clarke (2021); data familiarization; 2) systematic coding of data; 3) generating initial themes from coded and collated data; 4) developing and reviewing themes; 5) defining, refining and naming the themes; and 6) report writing (p. 4). All these six phases need to be blended whilst analysing a dataset which requires a researcher to be involved in a process of recursive analysis. This phase requires the researchers to immerse herself in the data, to read, to reflect, to question, to imagine, to wonder, to write, to retreat and to return to the data throughout the study (Braun & Clarke, 2021).

Findings

Table 2 shows the overall mean score which indicated students’ positive perception towards ORT as a tool for language practice (Mean = 4.0810). The students responded positively that ORT has helped to improve their command of the literary play, visualise the scenes in the play and relate to the characters featured in the play.

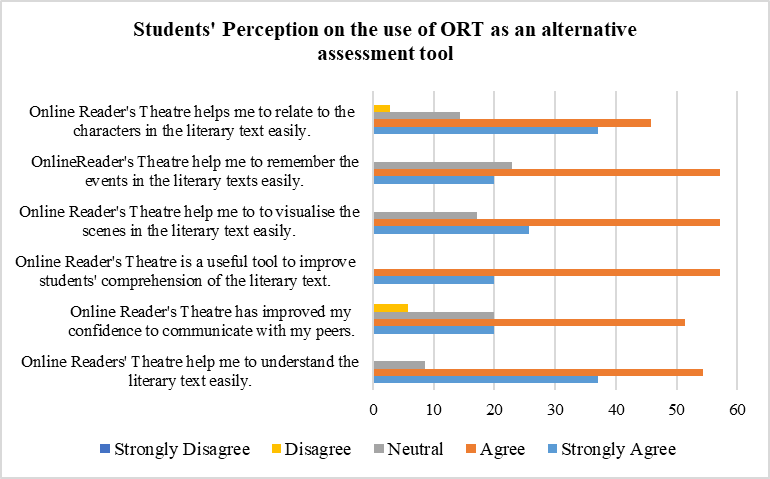

In addition, Figure 2 shows the results of the survey on learners’ responses to using ORT as a tool for language practice and literary reflection. To ascertain the answer, a seven-question Likert scale survey, with possible responses ranging from 5 - Strongly Disagree to 1- Strongly Agree.

From the figure, it can be deduced that higher scores indicate immense agreement of learners’ with each statement. Learners’ responses were positive for item 2 until 6 with an average of 55% from them agreed that the use of ORT as an alternative assessment approach has helped them to engage and comprehend the literary text and communication with their peers with much ease. Their affluent adaptation to the approach is most likely due to their generation’s inclination as digital natives, thus they have greater ability to cope with online learning (Rapanta et al., 2020). For item 1, 46% agree that ORT has helped the students to engage and interact with the characters from the play. Their understanding on the characters featured in the play is imperative not only to prepare them for the online staging of Reader’s theatre but also to demonstrate their critical analysis of the play. In addition, through the re-enactment of the characters, learners can understand the literary text further as they established connections by immersing themselves into the characters (Kabilan & Kamarudin, 2010; Rapanta et al., 2020). The findings from the research has clearly indicated that the adaptation of ORT as an alternative assessment tool in a literature class is approved by the majority of the respondents. This concurrs with findings from Fajarsari (2016) who asserted that the implementation of alternative assessment is influential in increasing student’s language skills ability and motivation as well as facilitating cooperative learning process.

The following is the thematic analysis for the findings from the final section of the survey;

Collaborative learning from remote locations

ORT provides opportunities for students to use their creativity in preparing and presenting their drama presentation from remote locations. During the pandemic, face to face learning was seized and classes were conducted fully online. Despite students were scattered at various locations, they still managed to come online and work collaboratively with their peers to complete the assessment. Many respondents described the experience of preparing their ORT as “fun”, “adventurous”, “a wonderful journey”, and “exciting”. The remote locations did not impede their effort in working together as they resorted to various tools like the messenger and online conferencing to communicate and discuss their ideas. The respondents further added that the experience of completing the assessment was particularly rewarding when receiving validation of their effort through peer-praising;

“All group members give their full cooperation, and we always praise each other’s effort” (S1)

Even though the pandemic has affected their learning, yet the students were motivated to complete their ORT despite most of them had never attempted such assessment task before. Most respondents expressed that their experience of group collaboration has been productive, and they particularly enjoyed the process of brainstorming and their discourse while they were ‘punching’ and ‘hitting’ ideas and listening to their members’ interpretation of how the characters should be portrayed in their ORT.

Cultivates creativity and innovative approaches in preparing the ORT

In delivering the ORT presentation, students were required to tap into their technological knowledge. The students were required to prepare their ORT just like how they would stage it in front of a live audience. Apart from familiarising themselves with the characters that they were going to play, they also need to figure out how to make their ORT as ‘realistic’ as possible. During this study, the Movement Control Order had not been lifted, thus students have limited opportunity to go outdoor and shoot their scenes. Despite this setback, the students managed to overcome the challenge by utilising the green screen feature and edited it according to the setting featured in the play. Some of the respondents described the experience as uplifting for they got the opportunity to hone their skills in video editing as well as learning from their peers who are more technological apt;

“…the quality of editing by my group members make me want to learn more about video editing” (S2) (see Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Being digital natives, the students were naturally apt at searching for the right technological tools to complete their assessment task. Their positive experience while preparing for the task indicated that even in crises, the learning experience was undisrupted, and students were fast at adapting themselves to the limitations caused by the pandemic.

Promotes deep learning and increased engagement with the literary text

Learning of literature may be found to be challenging as the texts are laden with expressive language and symbolism that entail students to amplify their engagement with the text. To help student to sustain their interest and motivation in learning literature which not only can be achieved by placing them in experiential learning environment that is enjoyable and stimulating, but also through imaginative and innovative alternative assessment like ORT. One of the matters that dampen students’ motivation to learn literature is when they knowledge and comprehension of the text are conventionally assessed through assessment like essay writing. Based on the feedback received from the respondents, ORT did not impose pressure on them like a conventional assessment does;

“the process of preparing the ORT was fun and adventurous. It was a productive assessment” (S3).

In addition, most of the respondents reported that the implementation of ORT as an alternative assessment has further motivated them to engage deeper into learning the play for they need to present their interpretation and comprehension through the roles that they were playing. They also reported that the provision of rubrics to assess their ORT has helped them to better plan their ORT video presentation. Through a well-designed and well-executed ORT, the students felt their effort was validated through increased knowledge, self-confidence, and literary awareness.

The open-ended items from the survey were analysed thematically. It is found that ORT as an alternative assessment tool is perceived to be constructive and effectual. Reader’s Theatre is designed with the intention to help learners to reflect on life through the themes and characterisation featured in the play as well as to sustain their interest in learning literature. Moreover, Reader’s Theatre is also a strategic tool to encourage learners to immerse themselves into the ‘shoes’ of the literary characters in order to form better understanding and perspectives about the characters (Bell et al., 2010; Kabilan & Kamarudin, 2010). This view is also evident in Ratliff (2000) to which he found Reader’s Theatre to be the key principle and stimulus to dramatise literature and positions students into a theatrical mind-set which would help them with their imagination and visualisation of the literary text. In other respects, the integration of ORT initiates a rewarding and nurturing learning journey as learners are engaged in creative and fun learning activity while learning literature (Shanthi & Jaafar, 2020). This implementation provides multiple benefits to learners: gaining new knowledge and experience and establishing presence within conducive and positive online learning setting. Furthermore, the production of ORT promotes collaborative learning which can help to increase student’s achievement and “practice the academic language” (Uribe, 2019a, p. 245).

Apart from that, the pedagogical practices for the studies of literature to generation of digital natives who have been argued to have limited interest in reading has to be further re-thought and re-designed. The focus of assessment should be shifted to providing continuous feedback that can help to optimise student’s learning outcomes which many students have found to be much rewarding and encouraging rather than on grades attainment. Students also become less anxious when completing an alternative assessment task compared to when sitting for an exam (Mansory, 2020). As alternative assessment is promoted to be implemented at all educational levels, instructors also need to be innovative in designing alternative assessment that is integrated with technologies. Alternative assessment that is imbued with technology is said to be less didactic, enjoyable and meaningful as well as able to foster autonomous learning and collaborative learning among learners within the online realm (Kirschner, 2015).

Although there is a debate that integration of technology into assessment is perceived to be only replicating existing assessment methods, on the contrary, technology offers massive opportunities for instructors to re-design existing models and practices as well as re-fashion the aim of assessment and its relationship with the attainment of learning outcomes (Shute et al., 2013; Timmis et al., 2016). Media tools and modalities like text, image, video, audio, and visualisations can be utilised for students to demonstrate their knowledge and skills. As physical contact became scarce due to social distancing during pandemic era, technology becomes an instrumental support for online learning. The flexibility and accessibility of technology highly supports collaborative learning using emerging technology like Web 2.0 which allows data sharing and “collaborative construction of knowledge” (Adams et al., 2022; Barton & Heiman, 2012; Timmis et al., 2016, p. 461). Through technology, education model at higher education can be innovated to be more versatile and flexible, therefore, making it more resistant to future domestic or global crises.

Conclusion

The study has shown that the reformulation of ORT using online platform has been well-perceived by the students. It is a useful tool that not only can help students to comprehend and cope with the demands of the literary text, also it is an effective alternative assessment approach which can help learners to engage meaningfully with their peers and instructor despite being confined in a remote learning environment. From the various literature, Reader’s theatre is often viewed as an additional and engaging learning activities not only in a literature classroom but also across disciplines which is proven to help to improve fluency, comprehension and as an avenue for students to immerse themselves within the context or setting relevant to the disciplines. In addition, through the staging of ORT, not only students are given the opportunities to demonstrate the attainment of learning outcomes through the display of their comprehension and interpretation of the literary play, also they are able to show their appreciation towards literary works. Moreover, this study also ascertains that ORT is an engaging and enjoyable alternative assessment approach which facilitates students’ effort in regulating their learning by being more autonomous. Moreover, this study also has indicated that ORT is also an effective strategy to promote collaborative learning via technological tools. Adding the digital platform dimension not only makes it a suitable alternative assessment to be applied in a literature classroom, it also improves the values, attributes and overall scholarship of Reader’s Theatre. The post-pandemic era serves as a catalyst for instructors to explore and experiment with creative alternatives in designing effective learning environment with embedded online technologies. The unprecedented event of the pandemic has become a useful lesson especially for academic practitioners in which it has initiated an emergent need for instructors to continuously re-examine their own teaching ideologies and keep themselves abreast on effective pedagogical methods and instructional design through professional development preparedness training as the future of teaching and learning becomes more precarious yet flexible and fluid. On a final note, in the era of post-pandemic, it is instrumental for instructors to continuously reflect and evaluate the effectiveness of their pedagogical practices especially in designing assessments while being attentive and alert to respond to future crises with richer yet flexible pedagogical models and practices.

Acknowledgments

This research is sponsored by the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme, Ministry of Higher Education – FRGS/1/2021/SSI0/UPNM/03/1. The authors would like to convey their appreciation to National Defence University of Malaysia for their continuous support in any research activities as well as to the Research Management Centre of National Defence University of Malaysia for providing their endless assistance for this research. In addition, the authors also would like to thank students of Languages and Cross-cultural Communication cohort 2020 for participating in this research.

References

Abd Rahim, F. (2021). Changing the mindset: Making meaningful assessment. In Alternative Assessment in Higher Education: A practical guide to assessing learning. Ministry of Higher Education.

Adams, D., Abu Samah, H., & Samat, S. N. A. (2022). Group-based assessment: Using multimedia presentation to promote collaborative e-learning. In Alternative Assessments in Malaysian Higher Education (pp. 95-104). Springer.

Angelo, T. A., & Cross, K. P. (2012). Classroom assessment techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers (2nd ed.). Jossey Bass Wiley.

Atifnigar, H., Alokozay, W., & Takal, G. M. (2020). Students’ perception of alternative assessment: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Translation, 3(4), 228-240.

Attwood, R., & Radnofsky, L. (2007). Satisfied—but students want more feedback. Times Higher Education, 14.

Bakar, E. W. (2021). Enhancing Literary Comprehension and Technology Engagement Via Digital Storytelling During A Pandemic Lockdown–A Qualitative Study on Malaysian Undergraduates. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 11(5), 156-170.

Barton, M. D., & Heiman, J. R. (2012). Process, product, and potential: The archaeological assessment of collaborative, wiki-based student projects in the technical communication classroom. Technical Communication Quarterly, 21(1), 46-60.

Bell, S. K., Wideroff, M., & Gaufberg, L. (2010). Student voices in readers’ theater: Exploring communication in the hidden curriculum. Patient Education and Counseling, 80(3), 354-357.

Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2011). Train-the-trainers: Implementing outcomes-based teaching and learning in Malaysian higher education. Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction, 8, 1-19.

Bloom, L. R., Reynolds, A., Amore, R., Beaman, A., Chantem, G. K., Chapman, E., Fitzpatrick, J., Iñiguez, A., Mozak, A., Olson, D., Teshome, Y., & Vance, N. (2009). Identify This…: A readers theater of women’s voices. International Review of Qualitative Research, 2(2), 209–228.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328-352.

Brown, J. D., & Hudson, T. (1998). The Alternatives in Language Assessment. TESOL Quarterly, 32(4), 653.

Corcoran, C. A., & Davis, A. D. (2005). A study of the effects of readers' theater on second and third grade special education students' fluency growth. Reading Improvement, 42(2), 105.

Cross, C. J. (2017). Undergraduate biology students' attitudes towards the use of curriculum-based reader's theater in a laboratory setting. Bioscene: Journal of College Biology Teaching, 43(1), 12-19.

Drew, I., & Pedersen, R. R. (2010). Readers Theatre: A different approach to English for struggling readers. Acta Didactica Norge, 4(1), Art-7.

Edström, K. (2008). Doing course evaluation as if learning matters most. Higher education research & development, 27(2), 95-106.

Fajarsari, L. A. (2016). Students’ perceptions to alternative assessment in English learning at SMA Kristen Satya Wacana Salatiga [Unpublished master’s thesis, Universitas Kristen Satya Wacana].

Flynn, R. M. (2007). Dramatizing the content with curriculum-based readers theatre, Grades 6-12. International Reading Association.

Guangul, F. M., Suhail, A. H., Khalit, M. I., & Khidhir, B. A. (2020). Challenges of remote assessment in higher education in the context of COVID-19: A case study of Middle East College. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 32(4), 519-535.

Guzzetti, B. L. (2002). Literacy in America: An encyclopedia of history, theory and practice. Santa Barbara, CA.

Haertel, E. (1992). Performance measurement. Encyclopedia of educational research, 984-989.

Hatzipanagos, S., Tait, A., & Amrane-Cooper, L. (2020). Towards a Post Covid-19 Digital Authentic Assessment Practice: When Radical Changes Enhance the Student Experience. EDEN Conference Proceedings (1), 59-65.

Janisch, C., Liu, X., & Akrofi, A. (2007). Implementing Alternative Assessment: Opportunities and Obstacles. The Educational Forum, 71(3), 221-230. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131720709335007

Jasper, M., & Rosser, M. (2013). Reflection and reflective practice: Professional development, reflection and decision-making in nursing and healthcare. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Kabilan, M. K., & Kamarudin, F. (2010). Engaging learners' comprehension, interest and motivation to learn literature using the reader's theatre. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 9(3), 132-159.

Kalamees-Ruubel, K., & Läänemets, U. (2012). Teaching Literature In and Outside of the Classroom. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 45, 216-226.

Kearney, S. P., & Perkins, T. (2014). Engaging students through assessment: The success and limitations of the ASPAL (Authentic Self and Peer Assessment for Learning) Model. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 11(3), 2.

Khanlou, N., Vazquez, L. M., Khan, A., Orazietti, B., & Ross, G. (2022). Readers Theatre as an arts-based approach to education: A scoping review on experiences of adult learners and educators. Nurse Education Today, 105440.

Kirschner, P. A. (2015). Do we need teachers as designers of technology enhanced learning?. Instructional science, 43, 309-322.

Liu, J. (2000). The power of Readers Theater: from reading to writing. ELT Journal 54(4), 354-361.

Lo, C.-C., Lu, S.-Y., & Cheng, D.-D. (2021). The influence of Reader's Theater on High School Students' English Reading Comprehension-English Learning Anxiety and Learning Styles Perspective. SAGE Open, 11(4), 215824402110615.

MacRae, N., & Pardue, K. T. (2007). Use of Readers Theater to Enhance Interdisciplinary Geriatric Education. Educational Gerontology, 33(6), 529-536.

Maistry, S. M. (2022). COVID-19 and the move to online teaching in a developing country context: Why fundamental teaching and assessment principles still apply?. In Academic Voices (pp. 175-183). Chandos Publishing.

Mansory, M. (2020). The significance of non-traditional and alternative assessment in English language teaching: Evidence from literature. International Journal of Linguistics, 12(5), 210-225.

McNiff, J., & Whitehead, J. (2002). Action Research – Principles and Practice. Routledge.

Nasab, F. G. (2015). Alternative versus traditional assessment. Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Research, 2(6), 165-178.

Neely, P., & Tucker, J. (2012). Using Business Simulations as Authentic Assessment Tools. American Journal of Business Education, 5(4), 449-456.

Ng, P. (2008). The Impact of Readers Theatre (RT) in the EFL Classroom. Polyglossia, 14, 93-100.

Nicol, D., Thomson, A., & Breslin, C. (2014). Rethinking feedback practices in higher education: a peer review perspective. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 39(1), 102-122.

Nugent, P. (2021). An Introduction to readers theatre. The Centre for the Study of English Language Teaching Journal, 9, 61-71.

Prodromou, L. (1995). The backwash effect: from testing to teaching. ELT Journal, 49(1).

Rahim, A. F. A. (2020). Guidelines for online assessment in emergency remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. Education in Medicine Journal, 12(3).

Rapanta, C., Botturi, L., Goodyear, P., Guàrdia, L., & Koole, M. (2020). Online university teaching during and after the Covid-19 crisis: Refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Postdigital Science and Education, 2(3), 923-945.

Rasisnski, T., Stokes, F., & Young, C. (2017). The role of the teacher in reader's theater instruction. Texas Journal of Literacy Education, 5(2), 168-174.

Ratliff, G. L. (2000). Readers theatre: An introduction to classroom performance [Paper presentation]. 86th Annual Meeting of the National Communication Association Seattle, Washington, USA.

Reeves, T. C. (2000). Alternative assessment approaches for online learning environments in higher education. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 23(1), 101-111.

Renandya, W., & Widodo, H. P. (Eds.). (2016). English language teaching today - linking theory to practice. Springer.

Schell, J. A., & Porter, J. R. (2018). Applying the Science of Learning to Classroom Teaching: The Critical Importance of Aligning Learning with Testing: Fennema Essay…. Journal of Food Science Education, 17(2), 36-41.

Shanthi, A., & Jaafar, Z. (2020). Readers theatre something old but still an assiduous tool to acquire English Language. Journal of Creative Practices in Language Learning and Teaching (CPLT), 8(1), 32-42.

Shute, V. J., Ventura, M., & Kim, Y. J. (2013). Assessment and learning of Qualitative Physics in Newton's Playground. The Journal of Educational Research, 106(6), 423-430.

Timmis, S., Broadfoot, P., Sutherland, R., & Oldfield, A. (2016). Rethinking assessment in a digital age: opportunities, challenges and risks. British Educational Research Journal, 42(3), 454-476.

Tsagari, D. (2004). Is there life beyond language testing? An introduction to alternative language assessment. Center for Research in Language Education, CRILE working papers (58).

Uribe, S. N. (2019a). Curriculum-based readers theatre as an approach to literacy and content area instruction for English language learners. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 35(3), 243-260.

Uribe, S. N. (2019b). Investigating the benefits of curriculum-based readers theatre for English language learners through an innovative professional learning community model. In Mertler, C. A. (Eds.), The Wiley Handbook of Action Research in Education. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

van Vuuren, E. J. (2022). Assessment in higher education during troubled times: The case of a South African arts module. In Academic Voices (pp. 161-174). Chandos Publishing.

Vanaki, Z., & Memarian, R. (2009). Professional ethics: Beyond the clinical competency. Journal of Professional Nursing, 25(5), 285-291.

Vasinda, S., & McLeod, J. (2011). Extending readers theatre: A powerful and purposeful match with podcasting. The Reading Teacher, 64(7), 486-497.

Villarroel, V., Boud, D., Bloxham, S., Bruna, D., & Bruna, C. (2020). Using principles of authentic assessment to redesign written examinations and tests. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 57(1), 38-49.

Vu, T. T., & Dall’Alba, G. (2014). Authentic Assessment for Student Learning: An ontological conceptualisation. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 46(7), 778-791.

Watkins, D., Dahlin, B., & Ekholm, M. (2005). Awareness of the backwash effect of assessment: A phenomenographic study of the views of Hong Kong and Swedish lecturers. Instructional Science, 33(4), 283-309.

Worthy, J., & Prater, K. (2002). The intermediate grades:" I thought about it all night": Readers theatre for reading fluency and motivation. The Reading Teacher, 56(3), 294-297.

Young, C. J., & Rasinski, T. V. (2018). Enhancing author's voice through scripting. The Reading Teacher, 65(1), 24-28.

Young, C., Durham, P., Miller, M., Rasinski, T. V., & Lane, F. (2019). Improving reading comprehension with readers theater. The Journal of Educational Research, 112(5), 615-626.

Zimmerman, B. S., Rasinski, T. V., Was, C. A., Rawson, K. A., Dunlosky, J., Kruse, S. D., & Nikbakht, E. (2019). Enhancing outcomes for struggling readers: Empirical analysis of the fluency development lesson. Reading Psychology, 40(1), 70–94.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 September 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-964-1

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

7

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-929

Subjects

Language, education, literature, linguistics

Cite this article as:

Bakar, E. W., & Sulaiman, F. (2023). Vision to Action: Exploring Online Reader’s Theatre as an Alternative Assessment Tool. In M. Rahim, A. A. Ab Aziz, I. Saja @ Mearaj, N. A. Kamarudin, O. L. Chong, N. Zaini, A. Bidin, N. Mohamad Ayob, Z. Mohd Sulaiman, Y. S. Chan, & N. H. M. Saad (Eds.), Embracing Change: Emancipating the Landscape of Research in Linguistic, Language and Literature, vol 7. European Proceedings of Educational Sciences (pp. 43-57). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.23097.5