Abstract

This mixed-method study had two aims. One was to explore Thai university EFL teachers' perceptions toward online education during the COVID-19 pandemic. The other was to exemplify the influential relationships between teachers' perceptions and their instructional practices. To do so, the researcher recruited 26 EFL teachers from four research universities in the Greater Bangkok Area. All completed and returned a questionnaire; 14 agreed to be interviewed; and 11 consented to classroom observations. Findings were discussed in twofold. Numerical data demonstrated teacher participants' neutral feelings toward online education. Descriptive data listed several factors influencing these teachers' capabilities with online education. They were, for example, prior experiences with online education, computer literacy, personal comfort, and digital readiness, to name only a few. The qualitative study also revealed that online platforms and students were the main factors that influenced changes in teachers' practices. Overall, findings of this current study revealed factors contributing to EFL teachers' readiness for the sudden shift to online education during the COVID-19 pandemic in Thailand. The mandatory sudden shift to online education left teachers without a choice. As a result, they tended to perceive more difficulties, particularly those who have limited experience. However, over time they found certain strategies along with the help to resolve the difficulties. This study also amplified teachers’ voices in calling for the betterment of future online teaching and learning through five strategies.

Keywords: Covid-19, English as a foreign language teaching, mixed-methods, teachers’ perceptions, online education

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic triggers the importance of online education because, in a sudden shift, teachers must use online platforms to deliver their classes. The sudden migration to online platforms left both teachers and students unprepared—mentally and physically. It also surfaces and augments the long-unsolved problems regarding integration: technical and computer literacy, among others. A previous study by Wintachai et al. (2020) reported their observation in a university in Bangkok that the sudden shift magnified the fragile education mode. It is caused by the lack of experience in utilizing online platforms and stiff curriculum which then create disruptions among the teachers, including concerns about teaching quality. Worse yet, students face dropout risks due to financial situations. On the bright side, collegial support is raising among teachers and the notorious hierarchical relationship is fading as senior teachers need help from tech-savvy junior teachers. In different universities, Todd (2020) explained that although teachers perceive online platforms as having more problems than benefits, they can solve them within a few weeks thanks to their school culture. At an autonomous university in Bangkok, Jansem (2021) found that all her teacher participants perceive the use of online platforms as practical. She further explained that the practicality perceived by the teachers were on three different level: high, acceptable, and low. However, her participants also voiced their concerns regarding online education, such as learning unproductivity, loneliness, limited classroom activities, financial statuses, learning styles, interaction, and attitudes.

Literature review

The framework for this study draws on the concepts of teachers' beliefs and voices. To contextualize the study, a review of previous studies that have examined similar phenomena in recent years is provided

Teachers’ belief

The current study follows four complementing-to-each-other views of teachers’ beliefs as guidance. Nespor (1987) explained that teachers' beliefs, as has been distinguished from knowledge, play a major role in teachers' practice and orientation. He suggested that beliefs lay in the teachers' episodic memory, which comes from experience or cultural sources of knowledge. Pajares (1992) posed a similar perspective to Nespor's (1987) notions of beliefs. He suggested that teachers' beliefs influence their perceptions and judgments. This eventually affects their behaviors in the classroom. Furthermore, he emphasized the connections between teachers' beliefs and other beliefs—as in other cognitive and affective structures, which Rokeach (1968) called attitudes. It implies that teachers' beliefs are mainly constructed based on teachers' experiences. This suggests that teachers' experiences are built from their roles, students, subject matter, and school. Kagan (1992) emphasized the idea that teachers' beliefs are generated from teachers' prior accumulated experiences. She explained that experiences influence teachers' creativity in terms of problem findings and solving in their practice. This skill, over time, accumulates experiences. It leads to changes in teachers' beliefs since they obtain more and more ideas developed by themselves and through observations of fellow practitioners.

Hargreaves (1996) vocalized the importance of teachers' voice as it is highly related to the school and teachers' role in restructuring and reforming school culture. Moreover, teachers' voice is not built based on their own perspective, but also on students' and parents' voice. It implies that listening to teachers' voices, particularly the marginalized and disaffected ones, allows the enhancement of the understanding of, not just about teachers, but also, "our systems and ourselves" (p. 17)

Furthermore, the connection established among ideas and experiences contributes to the development of teachers' beliefs. In response to this, it is crucial to identify and understand teachers' beliefs and their developing processes and factors that influence them, since it is the "very heart of teaching" (Kagan, 1992, p. 85). Moreover, if it is measured and extracted with reliable and valid tools, such as semi-structured interviews, it could be the best predictor of teachers' professional growth and give a better picture to conduct better pre-service teacher education.

Teachers’ perceptions of online education

Many previous studies documented both advantages and disadvantages of online education. Studies conducted prior to the pandemic seem to provide more advantages than disadvantages. This is possibly due to the preparation and intention that they have before integrating the online education to their practices (Banditvilai, 2016; Bhat et al., 2018; Dede et al., 2009; Dina & Ciornei, 2014; Hemrungrote et al., 2017; Heggart & Yoo, 2018; Iftakhar, 2016; Peterson, 2010; Parsons et al., 2019; Robinson, 2008; Samruayruen et al., 2013; Ventayen et al., 2018; Xiangming et al., 2020). In contrast, during the Covid-19 pandemic situation, more difficulties were documented. This is due to the sudden shift to online education. Teachers and students are left without choice other than to shift to online platforms to have their classes. Kim and Asbury (2020) stated that their participants felt stressed and uncertain. The teacher participants also expressed their concern about their students’ vulnerability. Zhou (2020) categorized lack of experience, students’ low motivation and self-management, and deterioration of physical and mental health as the three main inhibitors of effective online learning during the pandemic. Sepulveda-Escobar and Morrison (2020) reported low to no interaction between teachers and students and among students. Nambiar’s (2020) participants complained that their classroom felt less lively because of this. Wintachai et al. (2020) explained that their student participants need financial reinforcements to increase their class retention. More problems were reported by Hell and Sauro (2021). They found that teachers did not receive adequate training in integrating their online education with an online platform. Four of the six participants admitted that they did not have enough knowledge of the integration. The lack of training led to the depleting teaching confidence, the absence of communication, and time to design their online teaching. Teachers felt that they were left alone to figure out everything by themselves.

Research Methods

As this study focuses on teachers’ perceptions identification, a questionnaire, interviews, and online classroom observations were utilized to collect the data. The collection of the data using multiple tools also allows the researcher to enhance the validity of the research findings. The participants of this study were recruited through purposive sampling from 4 research universities in the Greater Bangkok Area. They were invited through email and voluntarily participated in the study.

The questionnaire was adapted from Ismail et al. (2010), Mollaei and Riasati (2013), and Mohsen and Shafeeq (2014). The adapted questionnaire was modified in terms of the number, scope, order of the items, wording, and categorization. Generally, there are 60 items in the questionnaire, and it consisted of three main parts. The first part consists of 8 items concerning the participants’ demography and previous experiences. The second part has 32 items aiming to measure the participants’ agreement with the usage of online platforms in their practice. The third part comprises of 20 items investigating any difficulties resulting from the participants’ integration of online platforms.

Semi-structured, one-on-one online interviews were addressed to consented 14 participants. There are 22 open-ended questions as the guiding questions. The questions were focused on the factors initiating teachers to use an online classroom platform, their experience, and the hindrances they have during their integration. Further, it also explored the strategies teachers used to overcome the hindrances, and how they alter their practice. The recorded interviews were conducted in English and lasted approximately 40 to 90 minutes. The average length of the interviews was 62.57 minutes. 222 pages of interview transcriptions were made with the help of Otter.ai.

Eleven teachers gave their consent for their online classroom to be observed. The researcher also asked for students’ verbal consent. They were asked to write “yes” or “understand” on the online platform’s chat box as an affirmation that they gave their consent to be observed. An observation note was used to record the observations.

Findings

Three major findings emerged from the analysis of data collected through questionnaires, interviews, and online classroom observations: (1) ambivalent gestures in teachers' use of online platforms, (2) factors affecting how teachers perceived the online platforms, and (3) two sources of changes in teachers' practices.

Measurement of teachers’ agreement towards online platforms in their practice

The quantitative data calculations revealed that teacher participants’ perceptions of the use of online platforms are ambivalent. The ambivalence—sometimes agreeing or disagreeing, was caused by several factors. The perceived feasibility of online learning platforms affects teachers’ perceptions (Jansem, 2021). In other words, the teachers’ mixed feelings were caused by the mixed feasibility that they experienced during the use of online platform. Some teachers perceived the feasibility, while others did not. Other than feasibility, “’outside’ influences” (Jansem, 2021, p. 100) played a role in determining the teachers’ perceptions.

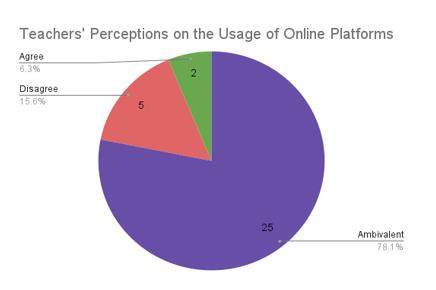

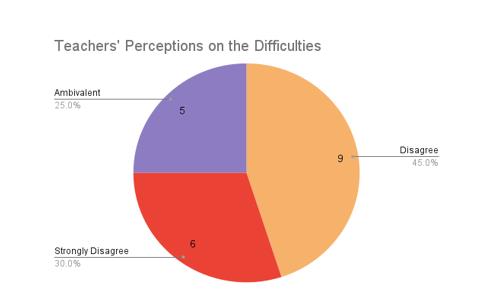

Based on Figure 1, from the 32 items asked to measure their agreement on the use of online platforms, more than two-thirds (78.1%; x̄: 3.33; σ: 1.23) of the items were rated an ambivalent level. These perceptions were also influenced by their prior experience and adaptation strategies. Only two items were rated as agree (x̄: 4.29; σ: .98) and the other 5 disagreed (x̄: 2.82; σ: 1.25). Furthermore, based on Figure 2, from the 20 items asked to identify their difficulties, almost half (45%) of the items were rated disagree (x̄: 2.39; σ: 1.25). Following that, there are 6 items (30%) rated strongly disagree (x̄: 1.71; σ: 0.91). These two perceptions showed that the teacher participants did not perceive many difficulties during their practices. This was caused by the time that they have to implement adaptation strategies, institutional support, and school culture. The rest 5 items were rated as ambivalent (x̄: 3.76; σ: 1.26). This is due to the diverse conditions and environment each teacher has.

The factors influencing teachers’ perceptions

The current study found a wide area of factors that influence teachers’ perceptions of online education. They are categorized into three groups consisting of a number of factors. All of the factors are explained as follows.

The teachers and their online learning platforms

This section discusses teachers’ perceptions of themselves; their prior experience in using online learning platforms in their classes and their computer literacy, the online learning platforms they have been using during the sudden move, their financial situation and their institution support that includes their demands as well. This section aimed at providing a thorough context on teachers’ conditions. A number of the teacher participants did not have some or extended prior experience in integrating online learning platforms into their teaching. They admitted that the limited experience has several drawbacks. The drawbacks were feeling difficulty in the initial period of the sudden move and worried and nervous about what will happen during the online learning due to the inadequacy in expectations. asserted “No, never. That's why it's hard for me to teach [online].” Similarly,shared her perceptions “At first, everyone was very worried and nervous because they never used any online platform before.”

In contrast, the teachers with some or extended prior experiences were better prepared and adjusted during the sudden move to online learning.explained how his prior experience has helped him to adapt and adjust to the sudden shift,

To me, it was not a shock. It was not like a big adjustment. Because in the US, when I first taught my first college-level writing class for native students, it was a hybrid. And I also had an experience teaching online classes twice. In 2018, I taught a Technical Writing class for my university. It was a summer class, purely online. And then January to May 2018, I taught another Technical Writing class for another university. And then when I came to Thailand to teach at Trail University, I continued to teach another online writing class for another university. So, online to me is not new.

One factor that could explain this is that teachers feel comfortable with the technologies. Another factor is the geographical setting. The participants are coming from urban areas and hence have better access to technology and supporting infrastructure (Hani et al., 2021). With their computer literacy, teachers asserted that they could prevent issues in their online classes, adapting better to the sudden move, and broadening their professional development.

For the online platforms, the teacher participants use various video conferences software such as Zoom meetings, Google Meet, Microsoft Teams, and Cisco WebEx. In addition to them, they also integrate several internet tools such as Kahoot, E-Book, OBS Studio, university developed LMS, Padlet, and others. They mentioned several characteristics of the preferred online learning platforms: (1) user-friendly, (2) simple to use, (3) provide features they need, (4) reliable, and (5) secure.shared his consideration in choosing an online platform,

Google Classroom is so easy. I appreciate that Microsoft Teams has some abilities through its complexity that Google doesn't have. But they definitely do not outweigh the difficulty in having to find an old assignment or something past.

The teachers explained that they have to purchase several supporting gadgets and tools during the sudden move. They asserted that they could afford the needed supporting gadgets such as laptops, computer tablets, stylus, extra monitors, mouse, and aiding set up such as an ergonomic chair, standing desk, and higher speed and stable internet plan. Although those expenditures added their financial cost, however, they were willing to invest (Lall et al., 2021). The result of the comfortable financial situation is digital affordances, although they observed that many of their students are financially struggling. The struggle leads to a digital divide.

The teachers admitted that their institutions provided training for them, particularly in the first year of the sudden move. The trainings were led by experts within or outside of their institution. They asserted that most of the trainings were about how to use the features on online learning platforms and less on digital pedagogy. They agreed that the trainings were helpful and necessary (Sangeeta & Tandon, 2021). However, they demanded more training focusing on how to teach with online learning platforms. Some teachers opted to not attend the training because it only focused on how to click.

The reasons the teachers favor online education

Teachers have three factors influencing their positive perceptions toward online education. Interestingly, they are not only coming from the nature of online education, but also from within themselves and administrators. In short, their institutions’ strategies and policies in dealing with online education, personal comfort, and the outcomes of online education to their students helped them to continue online education even after the Covid-19 pandemic is contained. Their institutions required the teachers to use synchronous learning with video conference platforms to virtually meet their students. Their institutions also advised giving the students time to adapt to the new mode of teaching and giving a one-week break prior to the final exam weeks to their students. Two teachers mentioned that their institution advised them to limit their online meetings with their students.

The teachers mentioned two forms of positive school culture that have helped them to adapt and survive the transition to online education—collaboration and IT Support. The teachers asserted that collaboration in the form of co-teaching could enhance their teaching experience and practice. However, one teacher noted that to achieve efficiency, co-teaching should act not only as a cosmetic. Another form of collaboration explained by the teachers is information sharing. Through this collaboration, the teachers could exchange teaching resources, online teaching tools, and new ideas for their online teaching. The teacher mentioned the availability of IT support or technicians to help them with preparing the online learning platforms account, preparing the online or hybrid class, and providing assistance related to technical problems. However, some of the teachers opt to go to a specific person or a group of colleagues whenever they face problems. The balkanization was mainly grounded on their closeness to one another (Hongboontri & Keawkhong, 2014).explained her preference “We had faculty members and IT support staff in the Line group. But usually, I don't consult that group. I have a group of friends and then we just chat there.”

Furthermore, the first personal comfort revealed from the data analysis is both the teachers and their students do not need to commute to their universities. The absence of this activity brings two benefits: alleviated commuting expenses and saving time. Other benefits were mentioned: they do not need to wake up early in the morning. This could be beneficial for those who need more sleep and could make more time for their families at home. Additionally, they could make use of the time between classes or breaks to do chores, have a home-cooked meal, and do their hobbies.

Teachers mentioned online platform features as one of the important benefits. They asserted that the features bring innovative teaching into their practice. For instance, cloud storage provides a centralized place to store and edit teaching materials. In addition, cloud storage has the ability to share and invite students to edit documents. The teachers asserted that feedback-giving and interactions become more feasible through this feature. The teachers further mentioned video recording features that helped their students to rewatch their online classes. This made it possible for the students to review their classes and helped those who cannot attend the scheduled class to not miss any lectures. Correspondingly, students can build a better understanding of the courses. More than that, the teachers mentioned that features in online learning platforms allowed their students to be autonomous learners.

The difficulties caused by online teaching

This section houses most of the influencing factors. There are four groups as a result of the data analysis: (1) teacher-related problems, (2) student-related problems, (3) environmental-related problems, and (4) classroom management.

Teacher-related problems

Health become the major issues for teachers during their use of online platforms. The teachers’ increasing workload and obligation to sit in front of their computers for hours bring disadvantages to their physical and mental health. They asserted that they have to go to a hospital due to office syndrome, vertigo, backache, and bladder problems. Prolonged screen time also causes dryness in their eyes. One teacher also reported that she gained weight as a result of her sedentary habits during the Covid-19 pandemic. Moreover, the burnout caused them stress. Isolation from their colleagues and social life, and students’ decision to turn off their cameras during the online class worsened their condition. Belinda shared her health deterioration,

I went to the hospital. I don't remember how many times because of the office syndrome. I've got vertigo symptom. I cannot walk. I vomit all the time. And it's because I've been sitting on my desk teaching all day long. And sometimes I've got six hours of class, like six hours for the whole day.

Student-related problems

The interview analyses found students’ personal characteristics such as shyness, introversion, short attention span, lack of curiosity, and complaining to be among of the problems in online education. Those internal factors led to the students being uncooperative by not answering the teacher’s questions, hesitating to express their thoughts, being unwilling to do the extra mile in classroom activities, and demanding higher grades. The teachers opined that one of the factors influencing their inwardness was a lack of social, face-to-face interactions with their peers. Especially freshmen who have not had the chance to meet their peers were observed to have higher difficulties to do group work.

Thirteen of fourteen interviewed teachers reported that their students are losing their university milieu during the sudden move to online learning caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. The loss of social life led to several problems. The teachers listed six of the problems: (1) failure to learn independency, (2) missing their friends and losing the chance to build meaningful friendships, (3) missing out on social university life, (4) lack of socialization with their peers, (5) loneliness, and (6) lack of building rapport ability. As a result, the teachers noticed many drawbacks: (1) leaving a void in their university memory, (2) declining mental and physical health, (3) difficulties in making groups and doing group work, (4) anxiousness, (5) decreasing motivation, (6) tend to not volunteer to answer the teachers’ questions, (7) classroom withdrawal, and (8) excluded from a group.

Environmental-related problems

The physical location in which the teachers and their students attend the online classroom affects their perceptions of online learning platforms. The teachers and their students have different places to attend the online class, whether it was based on their preferences or limitations. Two teacher participants reported one problem. Their toddlers were their main problem in online teaching. Their toddlers like to have their attention and most of the time, annoy them when they are teaching. On the other hand, the teachers observed a number of problems experienced by their students from their environments.

The problems come from two source of locations: (1) disturbing and (2) relaxing environments. The teachers asserted that most of their students turned off their cameras. This absence of visual cues makes them doubt the whereabouts of their students and whether they are paying attention to the class. Furthermore, the teachers also found that the disturbing environments made their students reluctant to answer their questions, online class withdrawal, and decreased motivation. Other digital distractions such as games, social media use, and multitasking could lessen students’ focus and cause broad deficiency (Liu, 2022). Furthermore, the teachers noticed that some of their students had to share one room with other people—parents, siblings, or roommates, which makes them distracted and cannot focus on the online class. Jessica shared one of her students’ stories,

I remember that there was one student, they told me that their environment at home wasn't really supportive of online learning. Because that student needs to help raising a very young kid. And she cannot go anywhere because she doesn't have her own room. And she needs to help take care of the baby.

The second environment, relaxing, was found to be a distraction for students as well. In students’ relaxing and convenient bedrooms—in which they attend the online class, the teachers assumed that some of their students are sleeping. One teacher found out that his student was attending the online class from a café that played loud music. The student’s decision costs their interaction.

Classroom management

The teachers asserted that they face several problems in their classroom management. The problems were caused by limitations on online learning platforms and students’ choice to turn off their cameras. Due to the limitations, the teachers have to repeat their feedback to their students. This particularly happened when they divide their students into several small groups in Breakout Room. As a consequence, teachers need to recalculate the time spent on each group as they have limited time with many groups they have to visit.

The teachers conveyed that they have limited verbal interaction between them and their students. Similarly, they observed poor interaction between their students and their peers. Isaac shared his experience,

Obviously, a lot less interaction, a lot less cues for how the students ought to act. And figuring out who this teacher is, and then when they can't figure these things out. I think there's a lot of resignation, there's a lot of just, I might as well not even try.

The teachers highlighted two main reasons their students have a low level of interaction; they are having low motivation and are shy. They further explained that interactions combined with other factors contribute to a more severe problem. For example, low motivation and low interaction contribute to students’ low focus and allow them to get distracted. Shyness led to students’ choice to turn off their cameras combined with low interaction contribute to students’ failure in building rapport with their teachers and peers. This further could lead to class resignation and lowering group retention and agency in the group project.

The next problem documented in the data analysis is online classroom size. It refers to the number of students in an online classroom. Of the 11 observed online classrooms, the smallest and the biggest classroom comprised of 10 and 56 students, respectively, with an average of 30.45 students per online classroom. The teachers surfaced their concern about the overcrowded online classrooms as it could decrease education quality (Azorín, 2020).

The changes in teachers’ practice

The analysis of the data resulted in two causes of change: online platforms and students.

Changes because of the online platforms

The teachers’ perceptions of the limitation, features, and format (synchronous or asynchronous) of the online learning platforms evoke changes in their teaching efforts, instructional strategies, time allocation, and tools. Due to the limitation, one teacher admitted that she changed her strategy from game-based to focus more on lecturing. Furthermore, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the teachers’ use of online learning platforms increasing to a new point higher than ever in their careers. This has led to a change in their instructional strategy from whiteboard- and paper-based, to cloud-based teaching. The cloud-based refers to the use of cloud storage to keep learning files such as materials and assignments. The new instructional strategy allowed the teachers to modify and share the learning materials without printing them as well as share and collect assignments from their students. Jason admitted this as he said “I use Google Docs. I think [it] is quite good. [It] is real-time. And you can see that students help each other; paraphrase sentences. I think this is good. Google Docs changed the way I teach.”

Changes because of their students

Empathetic changes were found during the data analysis. The teachers were aware their students have been through struggles during the Covid-19 pandemic. They tried to make learning not a burden for students. Thus, they changed their instructional strategies to be more flexible. The teachers admitted that they reduce the number of assignments. Although this is not a direct effect of the teachers’ use of online platforms, however, by reducing the assignment they expect their students would have less screen time and more time for themselves. This strategy also aimed at giving time for students to rest from their exhaustion—which led to fatigue, from their online classes.shared his empathetic change,

I try to understand students more. I know that they are very stressed. They just sit there in front of the computer alone. They do not see their friends. They do not sit next to each other. No chit-chats. So, I would say, I become a very kind teacher. During this time, the pandemic time. More kind than before.

Conclusion

The factors documented in this study influence the teacher participants’ perceptions positively and negatively. It can be concluded that most of the negative perceptions were generated from their limited experience and the sudden shift to online education due to the pandemic. Teachers with limited experience perceive more difficulties compared to those who have certain experience, however, they found certain strategies to deal with difficulties. Those findings are consistent with previous studies conducted by Orlov et al. (2021). Teachers’ prior experience in teaching with online platforms contributed a great role in “ameliorating the potentially negative effects of the pandemic on learning” (p. 3). This is in line with the data saying that the teachers did not find serious problems regarding technology integration. In the same vein, Yan and Wang (2022) found that teachers’ “digital competence developed before the pandemic” (p. 8) influences their ability to adapt to the abrupt change. They explained the three stages of the online switching process: preparing, adapting, and stabilizing. They argue the success of the three stages determines the effectiveness of online learning and the learning outcome.

Among the factors that emerged from the analysis of the data, the loss of students’ university milieu not only greatly impacted students but also teachers. This is because the students become more inward and uncooperative. Teachers cannot do much as students tend to turn off their cameras which then led to the teachers cannot see their visual cues. A report by Kaufmann and Vallade (2020) stated that their student participants feel lonely during the online classroom. The loneliness was related to their learning environment and rapport between them and their teachers and their peers. They added that the problems could increase online learning attrition rates. Similarly, Eberle and Hobrecht (2021) found that students have a decrease in social life quality, and indeed in need support in their self-regulation and ways to initiate and maintain their social interactions to achieve better online learning experiences. Those experiences are related to their academic satisfaction. The decrease in satisfaction could lead to decreasing performance (Kuo et al., 2014). The positive perceptions were gained from the features and innovative teaching methods brought by the online learning platforms to their practice. For those positive perceptions, they decided to keep using some of the online learning platforms even after the pandemic contained.

The factors documented in this study not only change teachers’ perceptions, but they also induce changes in their practices. The changes were divided into two based on the causes—online learning platforms and students. The teacher admitted that some of the changes are permanent as one of their efforts in following the advancement of technology. One of the reasons they considered the permanent change was because of the innovativeness the online learning platforms brought into their classroom. Other than that, they also understand that their institution also sees the importance of incorporating educational technologies in classes, not only for the sake of the educational innovation, but also the image of the institution.

The results of the current study offered contributions for stakeholders that includes authorities, teachers, online learning platform companies, and researchers. The documentation of teachers’ perceptions of online learning platforms during the Covid-19 pandemic could provide descriptions and documentation of how teachers recognize and act. Furthermore, the documentation also could be used as a foreground in inventing educational innovations for companies and authorities. Additionally, the research could be a thorough record of what happened during the pandemic for future research.

References

Azorín, C. (2020). Beyond COVID-19 supernova. Is another education coming? In Journal of Professional Capital and Community 5 (3–4), 381–390 Emerald Group Holdings Ltd. DOI:

Banditvilai, C. (2016). Enhancing students’ language skills through blended learning. Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 14(3), 223-232.

Bhat, S., Raju, R., Bikramjit, A., & D'Souza, R. (2018). Leveraging E-learning through Google classroom: A usability study. Journal of Engineering Education Transformations, 31(3), 129-135.

Dede, C., Jass Ketelhut, D., Whitehouse, P., Breit, L., & McCloskey, E. M. (2009). A research agenda for online teacher professional development. Journal of Teacher Education, 60(1), 8-19.

Dina, A. T., & Ciornei, S. I. (2014). Teaching Less Widely Used Languages with Qualitative Multimedia Resources. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 128, 246–50.

Eberle, J., & Hobrecht, J. (2021). The lonely struggle with autonomy: A case study of first-year university students’ experiences during emergency online teaching. Computers in Human Behavior, 121, 106804.

Hani, U., Naz, M., & Muhammad, Y. (2021). Exploring in-service teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs regarding online teaching: A qualitative multi-case study. Global Educational Studies Review, 6(2), 92-104.

Hargreaves, A. (1996). Revisiting Voice. Educational Researcher, 25(1), 12–19.

Heggart, K. R., & Yoo, J. (2018). Getting the most from google classroom: A pedagogical framework for tertiary educators. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 43(3), 9.

Hell, A., & Sauro, S. (2021). Swedish as a Second Language Teachers’ Perceptions and Experiences with CALL for the Newly Arrived. CALICO Journal, 38(2), 202–221. DOI:

Hemrungrote, S., Jakkaew, P., & Assawaboonmee, S. (2017). Deployment of Google Classroom to enhance SDL cognitive skills: A case study of introduction to information technology course. 2017 International Conference on Digital Arts, Media and Technology (ICDAMT), 200-204.

Hongboontri, C., & Keawkhong, N. (2014). School culture: Teachers’ beliefs, behaviors, and instructional practices. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 39(5). DOI:

Iftakhar, S. (2016). Google Classroom: what works and how? Journal of Education and Social Sciences, 3, 12–18.

Ismail, S. A. A., Almekhlafi, A. G., & Al-Mekhlafy, M. H. (2010). Teachers’ perceptions of the use of technology in teaching languages in United Arab Emirates’ schools. International Journal for Research in Education, 27(1), 37-56.

Jansem, A. (2021). The feasibility of foreign language online instruction during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative case study of instructors' and students' reflections. International Education Studies, 14(4), 93-102.

Kagan, D. M. (1992). Implication of research on teacher belief. Educational Psychologist, 27(1), 65–90.

Kaufmann, R., & Vallade, J. I. (2020). Exploring connections in the online learning environment: student perceptions of rapport, climate, and loneliness. Interactive Learning Environments. DOI:

Kim, L. E., & Asbury, K. (2020). ‘Like a rug had been pulled from under you’: The impact of COVID‐19 on teachers in England during the first six weeks of the UK lockdown. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(4), 1062-1083.

Kuo, Y. C., Walker, A. E., Schroder, K. E., & Belland, B. R. (2014). Interaction, Internet self-efficacy, and self-regulated learning as predictors of student satisfaction in online education courses. The internet and higher education, 20, 35-50.

Lall, M., Jain, S., & Singh, A. (2021). Teachers’ voices on the impact of COVID-19 on school education: Are Ed-tech companies really the panacea? Contemporary Education Dialogue, 18(1), 58–89. DOI:

Liu, Z. (2022). Reading in the age of digital distraction. Journal of Documentation. DOI:

Mohsen, M. A., & Shafeeq, C. P. (2014). EFL Teachers' Perceptions on Blackboard Applications. English Language Teaching, 7(11), 108-118.

Mollaei, F., & Riasati, M. J. (2013). Teachers’ perceptions of using technology in teaching EFL. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 2(1), 13-22.

Nambiar, D. (2020). The impact of online learning during COVID-19: students’ and teachers’ perspective. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 8(2), 783-793. DIP:18.01.094/20200802

Nespor, J. (1987). The Role of Beliefs in the Practice of Teaching. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 19(4), 317–328.

Orlov, G., McKee, D., Berry, J., Boyle, A., DiCiccio, T., Ransom, T., Rees-Jones, A., & Stoye, J. (2021). Learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: It is not who you teach, but how you teach. Economics Letters, 202. DOI:

Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of educational research, 62(3), 307-332.

Parsons, S. A., Hutchison, A. C., Hall, L. A., Parsons, A. W., Ives, S. T., & Leggett, A. B. (2019). U.S. teachers’ perceptions of online professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education: An International Journal of Research and Studies, 82(1), 33-42. Elsevier Ltd.

Peterson, M. (2010). Computerized games and simulations in computer-assisted language learning: A meta-analysis of research. Simulation and Gaming, 41(1), 72–93.

Robinson, B. (2008). Using ICT and distance education to increase access, equity and quality of rural teachers’ professional development. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 9(1).

Rokeach, M. (1968). A theory of organization and change within value‐attitude systems 1. Journal of social issues, 24(1), 13-33.

Samruayruen, B., Enriquez, J., Natakuatoong, O., & Samruayruen, K. (2013). Self-regulated learning: A key of a successful learner in online learning environments in Thailand. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 48(1), 45-69.

Sangeeta, & Tandon, U. (2021). Factors influencing adoption of online teaching by schoolteachers: A study during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Public Affairs, 21(4). DOI:

Sepulveda-Escobar, P., & Morrison, A. (2020). Online teaching placement during the COVID-19 pandemic in Chile: Challenges and opportunities. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(4), 587-607.

Todd, W. R. (2020). Teachers’ perceptions of the shift from the classroom to online teaching. International Journal of TESOL Studies, 2(2), 4–16. DOI:

Ventayen, R. J. M., Estira, K. L. A., De Guzman, M. J., Cabaluna, C. M., & Espinosa, N. N. (2018). Usability evaluation of google classroom: Basis for the adaptation of gsuite e-learning platform. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, Arts and Sciences, 5(1), 47-51.

Wintachai, J., Khong, T. D. H., & Saito, E. (2020). COVID-19 as a game changer in a Thai university: A self-reflection. PRACTICE, 1-7.

Xiangming, L., Liu, M., & Zhang, C. (2020). Technological impact on language anxiety dynamic. Comput. Educ., 150, 103839.

Yan, C., & Wang, L. (2022). Experienced EFL teachers switching to online teaching: A case study from China. System, 105. DOI:

Zhou, Z. (2020). On the lesson design of online college english class during the COVID-19 pandemic. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 10(11), 1484-1488.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 September 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-964-1

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

7

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-929

Subjects

Language, education, literature, linguistics

Cite this article as:

Hendrajaya, M. R., Hongboontri, C., & Boonyaprakob, K. (2023). EFL Teachers' Perceptions of Online Education Amidst Covid-19 Pandemic in Thailand. In M. Rahim, A. A. Ab Aziz, I. Saja @ Mearaj, N. A. Kamarudin, O. L. Chong, N. Zaini, A. Bidin, N. Mohamad Ayob, Z. Mohd Sulaiman, Y. S. Chan, & N. H. M. Saad (Eds.), Embracing Change: Emancipating the Landscape of Research in Linguistic, Language and Literature, vol 7. European Proceedings of Educational Sciences (pp. 377-390). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.23097.34