Abstract

With the increase of overseas construction projects, there is great demand for a comprehensive understanding of construction contracts (CC) from the language perspective. But such perspectives are understudied when exploring CC. This study aims to tap language features from the lenses of genre analysis (GA), which is conducive to a better understanding of CC. In this study, a corpus-driven exploration of CC was carried out, in which striking language features were revealed in a visualized manner by adopting the Multidimensional Analysis Tagger (MAT). The study found that nouns and normalization were dense in CC, with attributive adjectives and total prepositional phrases frequently used. When it comes to the overall generic features of the CC used in this corpus, it was found that CC belong to the written genre with the informational, non-narrative, context-independent, persuasive, and abstract generic feature. Those features further make CC formal in style, explicit in communicative purposes, objective in stance, and authoritative in position. The language features in question are not out of thin air but the results of the evolution of professional practices (PP) and professional cultures (PC). Limited as the language features have been discussed, insight can still be obtained, which is conducive to further studies.

Keywords: Critical genre analysis, construction contracts, genre analysis, language features

Introduction

CC refer to the agreements between two or more parties for carrying out a construction project, they identify the rights and obligations of relevant parties, determine the dispute settlement mechanisms and other issues to safeguard the interests of all relevant parties, and will be enforced according to the system of laws applied to the contracts (Ning & Wu, 2019; Sweet et al., 2015; Wang & Yang, 2016). Along with the technological complexity ranging from materials and trades to complex facilities, a construction project may also involve builders, designers, regulators, purchasers, and users of buildings (Murdoch & Hughes, 2008). That determines that CC are rather complex in structures, contents, and styles. From this perspective, a better interpretation of CC needs a thorough exploration.

As China deepens its integration into the international community, an increasing number of multinational corporations have swarmed into China, bidding for construction projects. In the same manner, many Chinese companies are going abroad with the aim of winning overseas projects. According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China (2022), as of the end of 2021, the total value of the newly signed CC is $201.7 billion. In such a surge of construction exchanges, CC play an indispensable role in carrying out construction projects. Hence, a comprehensive understanding of English CC is crucial for those engaging in or will engage in overseas construction projects. As a legal genre, CC possess all the complex features in content and language (Orts, 2015). In many cases, the most daunting task is not content knowledge but the language barriers that pose a great challenge to the understanding of contracts for practitioners (Qi, 2004; Wang & Li, 2016). This is especially true in China for the fact that English is just a foreign language and not all the people engaging in English contracts are proficient in English (Ning & Wu, 2019). In this sense, if one wants to have a better understanding towards CC, he/she must be familiar with how CC are structured, what language styles (generic feature) to employ, what words to use in a specific situation, how to manipulate grammatical elements to meet objectives, and how to use rhetorical strategies to cater to given situations (Rasmussen & Engberg, 2017; Wang & Li, 2016). To put it simply, getting to know about the language features of CC is a necessary access to a comprehensive understanding (Li et al., 2020). In this sense, efforts are in great need to obtain a comprehensive understanding of them, and more studies need to be carried out from language perspectives.

When it comes to the studies concerning CC, two tendencies can be found. Some studies deal with the problems arising from the complexity of CC (Elkhayat & Marzouk, 2022). Others focus more on the issues concerning the laws, regulations, customs, cultures, and so on (McNamara & Sepasgozar, 2021; Wang & Li, 2016). It can easily be seen that most studies are interested in issues concerning professional practices and professional cultures. As for the studies of CC concerning the language perspectives, only several studies can be found. For instance, Liu (2008) explored the language features of the FIDIC conditions from the Functional Stylistics perspective. This study found that the FIDIC contracts possessed unique features at the field & ideational, tenor & interpersonal, and mode & textual levels. Though only focusing on specific linguistic aspects of one contract for construction, it demonstrated that it was feasible to carry out the research of CC from the language perspective. Based on an overseas construction contract, Cheng (2009) made a thorough study on the contract’s language features, including modal verbs, normalizations, adverbials, adverbial clauses, attributive clauses, and so forth. Limited as the research scope was, it shed new light on the lexical and grammatical features of CC. There are also other studies concerning the language of CC, but most studies are more concerned with why language is important and how to write a specific part of CC (Lv, 2015; Ning & Wu, 2019; Wang & Li, 2016). As has been reviewed, no comprehensive studies of CC have attached importance to their general genre features (Nie, 2021).

To make a thicker study of CC, theories of GA can be of use for their advantages. According to genre theories, the genre can be deemed as getting things done with language (Martin, 1985). In this sense, language is an indispensable instrument for a given genre to achieve specific purposes. GA is deemed efficient in identifying linguistic features of specific genres (Flowerdew, 2015; Hyland, 2004). GA can be carried out at two levels, namely, the textual level and the contextual level (Hyland, 2004; Hyon, 2018). At the textual level, genre theorists first focus on the lexico-grammatical features and their specific functions in genres. Systemic Function Grammar (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004) holds that there is a connection between linguistic forms and their meanings, and different forms can produce different meanings. In other words, a genre may have its distinct features lexically and grammatically to realize specific purposes (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004). Thus, the exploration of lexical and grammatical features is the prerequisite for a thorough understanding of a given genre (Bhatia, 1993, 2008, 2017; Hyland, 2004; Hyon, 2018). Through continuous exploration, Bhatia (1993, 2008, 2017) finally formulated the critical genre analysis (CGA), which is conducive to understanding professional genres in a broader sense. From a contextual perspective, CGA narrows down the scope to the professional contexts of given genres from the broad socio-cultural contexts. In doing so, Bhatia shifts the research focus from decoding genres at lexico-grammatical and structural domains to how language semiotics are organized to conform to professional practices and professional cultures. Attaching importance to professional practices and professional cultures is one striking feature of CGA because they can shape the overall generic features, the lexico-grammatical appropriation, and move organization. According to Bhatia (2017), professional practices in CGA involve choosing a proper language and other semiotic resources to adapt to professional activities in which different genres can be appropriated to fulfill vocational objectives. Such activities include the usual practices concerning the implementation of a specific task. Professional cultures, on the other hand, focus on how cultural factors (norms, conventions, professional identities, and goals & objectives, which are closely related to a given genre) affect the use of language resources (Bhatia, 2017). Those two variables are deeply interrelated with the given genre that is being used in a certain professional situation. Another outstanding feature of CGA is its concentration on interdiscursivity. Interdiscursivity refers to the employment of discursive elements of different genres in one specific genre for which institutional and social meanings from other discourses and social practices may help the meaning construction in the target genre (Candlin & Maley, 1997; Feng, 2019). This term, borrowed from discourse analysis, can mirror the nature of the target professional genre (Bhatia, 2017). Thus, understanding the interdiscursive nature of a genre is propitious to rigorous and comprehensive demystification (Bhatia, 2017).

As discussed previously, GA is an effective tool for addressing text-internal issues (Swales, 1990, 2004). On the other hand, CGA provides new means for exploring the correlations between languages and professional contexts, which belongs to the text-external scale (Bhatia, 2017). In this respect, integrating GA and CGA perspectives to study a given genre will provide a holistic picture of its language features.

Studies concerning text-internal factors are numerous, with the research focuses ranging from lexico-grammatical features (Biber, 1988; Biber & Conrad, 2019; Hyland, 2004, 2005; Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004) to moves (Bhatia, 1993; Biber et al., 2007; Swales, 1990, 2004). As for studies concerning text-external factors, Bhatia (2004, 2008, 2017) carries out a series of comprehensive explorations of genres of advertising, fundraising, memorandum, corporate, arbitration, and legislation. However, as reviewed by the writer, most studies just deal with genres from one perspective, GA or CGA. There are fewer comprehensive studies concerning genres through the integration of GA and CGA. When it comes to CC, there seem to be no studies carried out under the scope of GA or CGA, not to mention to integrate them. This study attempts to take advantage of GA and CGA and depict a holistic picture of language features concerning CC.

Research Methods

This study was corpus-driven, in which a mixed method was employed. In the quantitative aspect, a corpus of five DBB contracts was built, with the total number of words being 146,338. The reasons for selecting such a small corpus were that DBB contracts are conventionalized in format and rigid in language, and a small corpus of legal texts can also provide enough information about the language features of the target genre (Bhatia, 1993). To ensure the validity, all five contracts are real contracts, with two from the archive of our university, one from a business partner of our university, and two downloaded from the Law Insider website providing real CC to a paid member. All the information concerning privacy was removed from the contracts on request. The contracts were transcribed or transformed into “txt.” format with Baidu APP or manually. Then the texts processed were further checked by the writer and two teachers familiar with CC. The texts were processed by the MAT, a software for processing texts. At the qualitative level, the results were analyzed from CGA scope based on textual analysis and Functional Grammar. Small as the corpus may seem, it can shed light on the generic features of CC for its rigid and conventionalized nature.

Based on Biber’s study concerning text features from multi-dimensional aspects, the MAT is a program for Windows to produce a series of visualized diagrams revealing lexico-grammatical features of a corpus or the target texts along with the statistics information in detail (Nini, 2019). This program explores the target texts or corpus with the dimensions put forward by Biber (1988) and can classify the target genre into specific genre types through a computerized process. The biggest advantage of the program is that it can bring forward the statistics of 67 linguistic variables and generate visualized results from diverse dimensions that reveal the detailed features of a given text. Because of the limitation of the space, the study will focus on the dimensional features and the variables whose frequencies are pretty striking.

As far as the generic features are concerned, this study mainly focused on overall styles based on Biber’s multi-dimensional scale because they can present the genre features from multiple perspectives. As mentioned early, in the MAT program, there are six dimensions, including the dimension ofthe dimension of, the dimension of, the dimension of, the dimension of, and the dimension of. When texts of a given genre are put into the program, the program will generate scores based on the textual features. The ranges of the scores will display the features of the texts selected from a different perspective, as displayed in Table 1. Besides, this program can be employed to generate detailed statistics about the overall language features of a given genre in graphs, revealing the outstanding linguistic features clearly and convincingly.

As for the research procedure, the five CC were first collected, and then the texts were transformed into “txt.” format. Next, the transformed contracts were put into the MAT v.1.3.2. Then results concerning lexico-grammatical features and overall generic features can be produced. Finally, the results were interpreted from the CGA lens.

Findings

Linguistic Features

The study went deeper via the multidimensional analysis to obtain a thicker description of CC, which was realized by the application of the MAT program. The MAT program can process the text in “txt.” format. Thus, the transformed contracts from the previous stage are usable directly. After inputting the data into the program, a series of visualized results were produced. At the linguistic level, statistics of linguistic variables of the corpus were generated. Because of the limited space of the study, it was difficult to exhaust all 67 variables. Thus, the study only retained the outstanding features with a variable frequency exceeding five times per hundred tokens (including five) or nearly zero. By studying the results generated by the MAT program, we can find that the average word length (AWL) is 5.27. The nouns (NN) and nominalizations (NOMZ) account for about one-third of the corpus, with an even dispersion in the contracts of the corpus. Moreover, total prepositional phrases (PIN) emerged more than 13 times per hundred tokens of the corpus, and they dispersed evenly too. Attributive adjectives (JJ) are also quite frequent in CC, with a frequency of five times per hundred tokens. Contrary to the high frequency of some variables, we have found that concessive adverbial subordinators (CONC), conjuncts (CONT), discourse particles (DPAR), hedges (HDG), direct WH-questions, and that adjective complements (THAC) are in the least use in the CC.

The dominance of the nouns and nominalizations can be interpreted from professional scopes. From a professional practice perspective, every detail needs to be considered to guarantee the smooth progress of the construction and safeguard the interests of related parties. Thus, CC is used to identify all the relevant details and set a clear boundary of rights and duties of the parties involved. Nouns and nominalizations can better meet the requirement for they can increase the density to the maximum limit (Carlo, 2015), which will be able to hold as much information as possible. As revealed in Example 1,,, o,,,,,, and depict a detailed and explicit road map about in what condition a mechanism will be triggered, and what to do to cope with the situation. In such a manner, CC will effectively fulfill its functions of serving the construction process. From the professional culture perspective, it has been conventionalized that a contract should be formal to give expression to its authority (Qi, 2004). The abundant use of nouns and nominalizations can add extreme formality (Carlo, 2015).

Example 1

In the event that the Contractor shall fall behind schedule at any time, for any reason, and such delay is adversely affecting the County’s timely occupation of the Project for its intended purpose, the County shall be entitled to direct acceleration or re-sequencing of the Work to bring the Project back on schedule. The Contractor shall reserve in each of its subcontracts entered in connection with the Project, --- --- (Excerpt from Contract 1)

As for the wide use of total prepositional phrases, it can be viewed from the Functional Grammar perspective. According to Halliday and Matthiessen (2004), propositional phrases can be used as circumstantial adjuncts, interpersonal adjuncts (not frequently), and conjunctive adjuncts like the conjunction groups. For example,,,, anddefine the circumstances or conditions for certain measures to be taken. From the professional perspective, the construction process needs the coordination of diverse elements. The coordinated relations will be clarified in CC, which is subsequently reflected in total prepositional phrases.

Based on the previous discussion, it will not be difficult to understand the fact that attributive adjectives are frequently used. To explicitly present the information, the key terms need to be clearly delimited (Liu, 2018).are effective devices to realize such a function. Meanwhile, for the sake of compactness, conciseness, and information density, attributive adjectives are also useful, for they can carry particular meanings. Furthermore,can reflect professional cultures in one way or another. As we can see from Example 2,,,,,, andset a clear limit on the terms they modify. Simultaneously, additional information is provided as well. In this example, and are essential norms for contracting that are highly valued by all parties involved.

Example 2

The Contractor acknowledges that the respective contracts require the Owner and the Design Professional to proceed with the Project on the basis of trust, good faith, and fair dealing, and they will take all actions reasonably necessary to ensure the Project proceeds to completion within the Owner's time and budgeting constraints. The Contractor also acknowledges that the Design Professional is to perform all tasks and services required of it under the Design Professional Contract. The Contractor further acknowledges that, in order for the Design Professional to perform its obligations, the Design Professional requires certain materials, information, or other submissions pursuant to the Contract Documents from the Contractor (Excerpt from Contract 2).

As for the shortage of concessive adverbial subordinators (CONC), conjuncts (CONT), discourse particles (DPAR), hedges (HDG), direct WH-questions, and that adjective complements (THAC), the reasons are as follows: CC are written legal documents that are formal, compact, and concise (Lv, 2015). This means written language is the prerequisite for drafting CC. Thus, discourse particles are inappropriate for they usually serve the spoken context. At the same time, it has been deemed a common practice that legal language should be formal, compact, and concise (Bhatia, 1993, 2017). In view of this, concessive adverbial subordinators (CONC), conjuncts (CONT), and hedges (HDG) cannot meet such a standard. Concessive adverbial subordinators (CONC) and conjuncts (CONT) usually present themselves in a complex manner indirectly to achieve their specific aims. As for hedges (HDG), real intentions are usually revealed in an implicit manner.

As can be seen from Example 3, long sentences are preferable in CC, in which elements are usually juxtaposed explicitly. Such structures can reveal the information directly so as to eliminate vagueness (Han & He, 2012). The reasons for such drafting styles are two-fold. On the one hand, the drafting of CC has been conventionalized, which means drafting in a formal way has been a norm accepted by those in the construction industry. We may say it is professional cultures that determine the ways CC are written. Moreover, the complex nature of the construction process needs CC to be more inclusive, concise, and authoritative. Therefore, CC need specific language features to serve the smooth progress of the construction project as well as the interests of the stakeholders.

Example 3

Notwithstanding any other provision of the Contract Documents to the contrary, no general partner, limited partner, member, officer, shareholder, director or other representative of Owner or of any partner, member or manager of Owner shall have any personal liability for the performance of any obligations under the Contract Documents, and no monetary other judgment shall be sought or enforced against any such persons or their assets. (Excerpt from Contract 2)

For the limit of the space, not all linguistic features can be analyzed; however, we can still gain insight into the language features of CC, which proves that further exploration is feasible and meaningful.

Overall Generic Feature Analysis

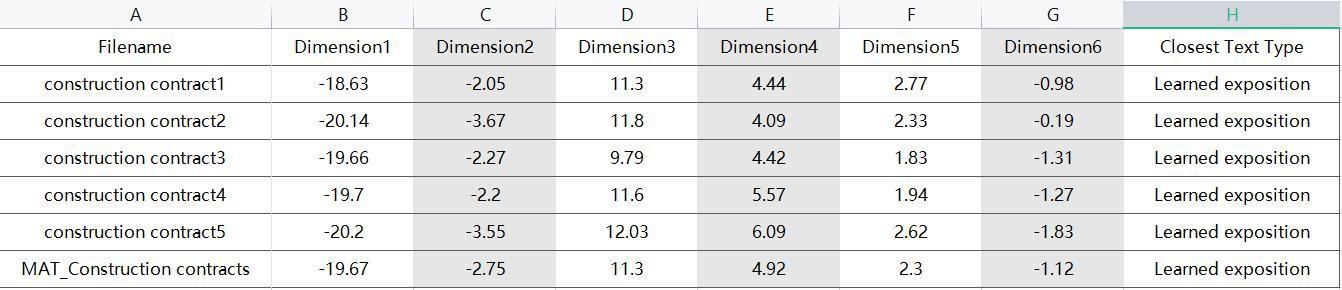

Along with the detailed linguistic features, generic features were analyzed in this section. This study mainly focused on the features of on six dimensions proposed by Biber (1988). The MAT program automatically undertook the analysis concerning the general genre features and generated the results in graphs. As displayed in Figure 1, each construction contract’s scores and the average scores of every dimension were visualized. The scores, as elaborated in the generated graph, revealed that all the CC in the corpus are similar to the learned exposition after a synthesized analysis. According to Nini (2019), learned expositions are expositions that are information-oriented, trying to provide information in a formal and systematic manner. Official documents, academic prose, and press reviews belong to this generic type.

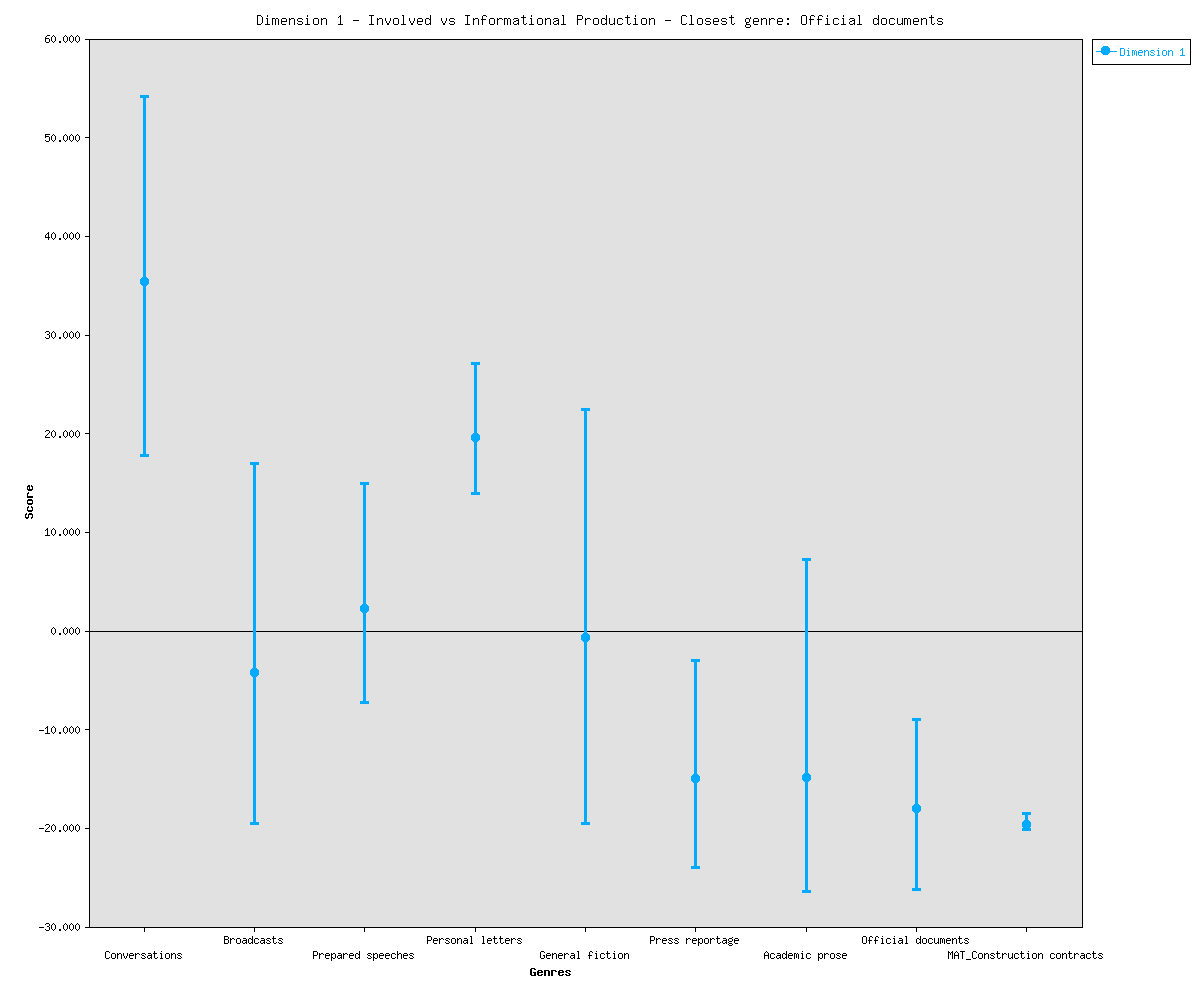

Meanwhile, the program made a comparative analysis with other common genres (including conversations, news broadcasts, speeches, letters, general fictions, press reportage, academic prose, and official documents) and produced six visualized graphs concerning different dimensions. These visualized graphs revealed the generic features of the CC from different perspectives. On the first dimension, which focuses on whether the genre is for information giving or involving the target audience, CC have an average score of 19.67 and shared some features with broadcasts, general fiction, press reportage, academic prose, and official documents, making its closest genre official documents, as revealed in Figure 2. That suggests that the CC are dense with information and full of nouns, long words, and adjectives (Biber, 1988; Nini, 2019; Tessuto, 2012). As was discussed previously, CC are used to safeguard the smooth progress of construction projects, which renders the complex nature of CC, suggesting that they must be inclusive of as much information as possible. This is the very reason for their similarities with broadcasts, general fiction, press reportage, academic prose, and official documents, for they are all loaded with information. That feature also serves to achieve their communicative purposes, which are also the reasons for CC to display some features possessed by other genres. In other words, interdiscursive elements can be tools for the realization of specific communicative purposes. As is shown in Example 4, technical terms like earthing system, electromechanical stress, earth fault, human and property safety and protection, codes and regulations, copper clad steel rods, bare copper, and ground grid are all crucial elements to condense as much information as possible in the concisest manner.

Example 4

Proposed earthing system shall withstand any electromechanical stress caused by earth fault conditions. The system shall be designed to ensure human and property safety and protection, as recommended by applicable codes and regulations. The earthing/grounding system consists of underground copper clad steel rods to be interconnected with bare copper wired to form a ground grid. All non-current carrying metal parts of electrical equipment shall be grounded... (Excerpt from Contract 3)

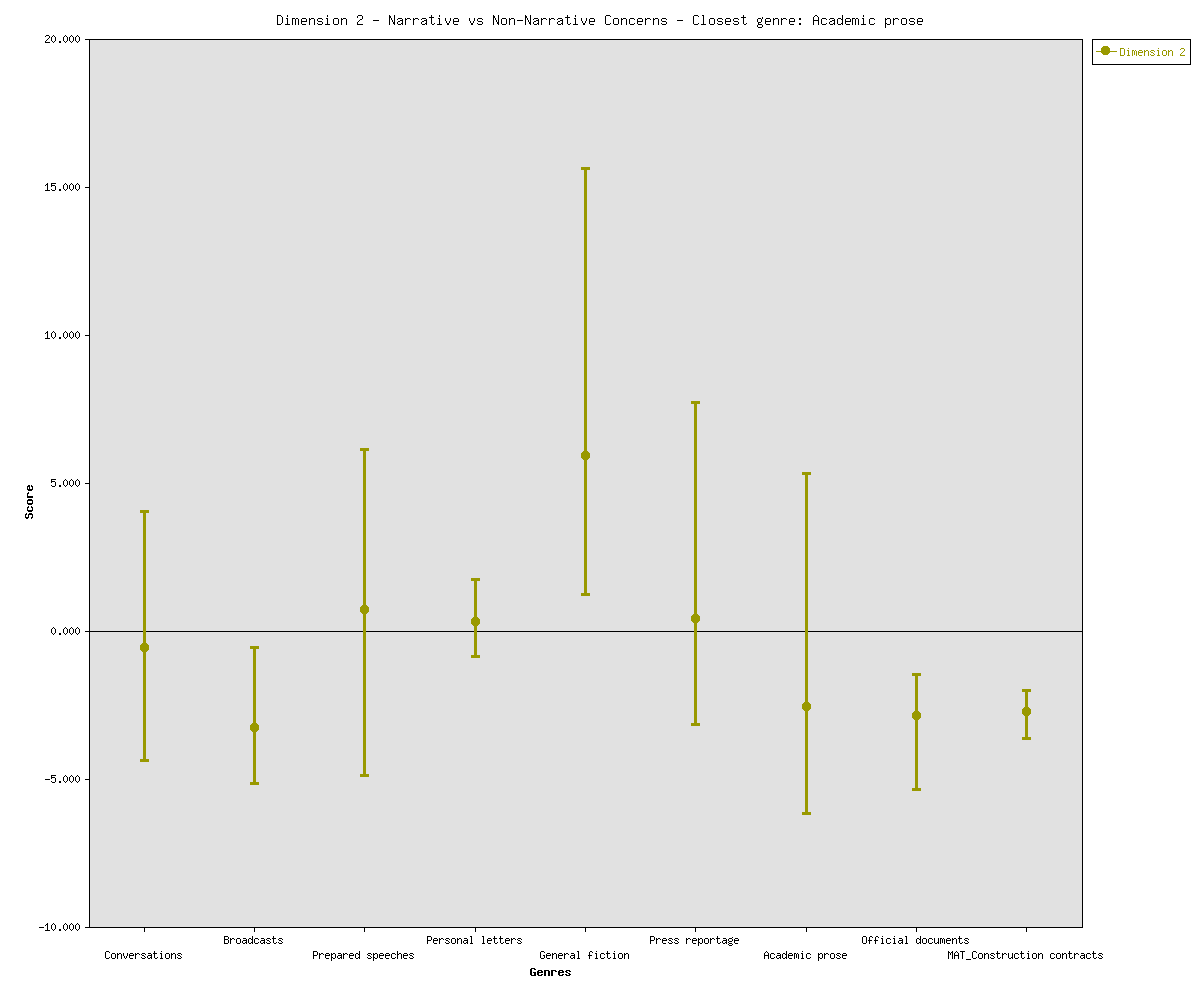

On the second dimension, Narrative vs Non-Narrative Concern, the score of CC was -2.75, which suggests that the CC in this study are non-narrative in nature and past tense is not frequently used. In this respect, CC are closest to academic prose in generic features displayed in Figure 3. Such a feature is due to the fact that CC are the tools for clarifying rights and obligations, the procedures for carrying out certain tasks, the mechanism for settling disputes, and other issues related to the construction process. As for the lack of past tense, it is due to the fact that CC are drafted to guarantee the projects to be carried out. Thus, simple future tense and present tense are more suitable in this respect, which are all the professional practice-related factors that exert their influences on the generic features. From the professional culture perspective, it has been conventionalized that CC should be formal and authoritative. Such features can be found in Example 5, in which sentences are all simple in structure and information-loaded, making them more of instruction and stipulation. Furthermore, the tense of the sentences is more future-oriented. To sum up, being non-narrative and formal is a striking generic feature of this dimension.

Example 5

Contractor shall ensure that the existing telecommunications network outside of the terminal is not interrupted, neither temporarily nor permanently. In this regard, Contractor shall be responsible for all temporary and/or permanent measures, including but not limited to rerouting telecommunications cables installation of conduits, ducts, duct banks, junctions, pits, connections, etc. to ensure that continuous service of the existing telecommunications network is provided to all areas within K Port. (Excerpt from Contract 4)

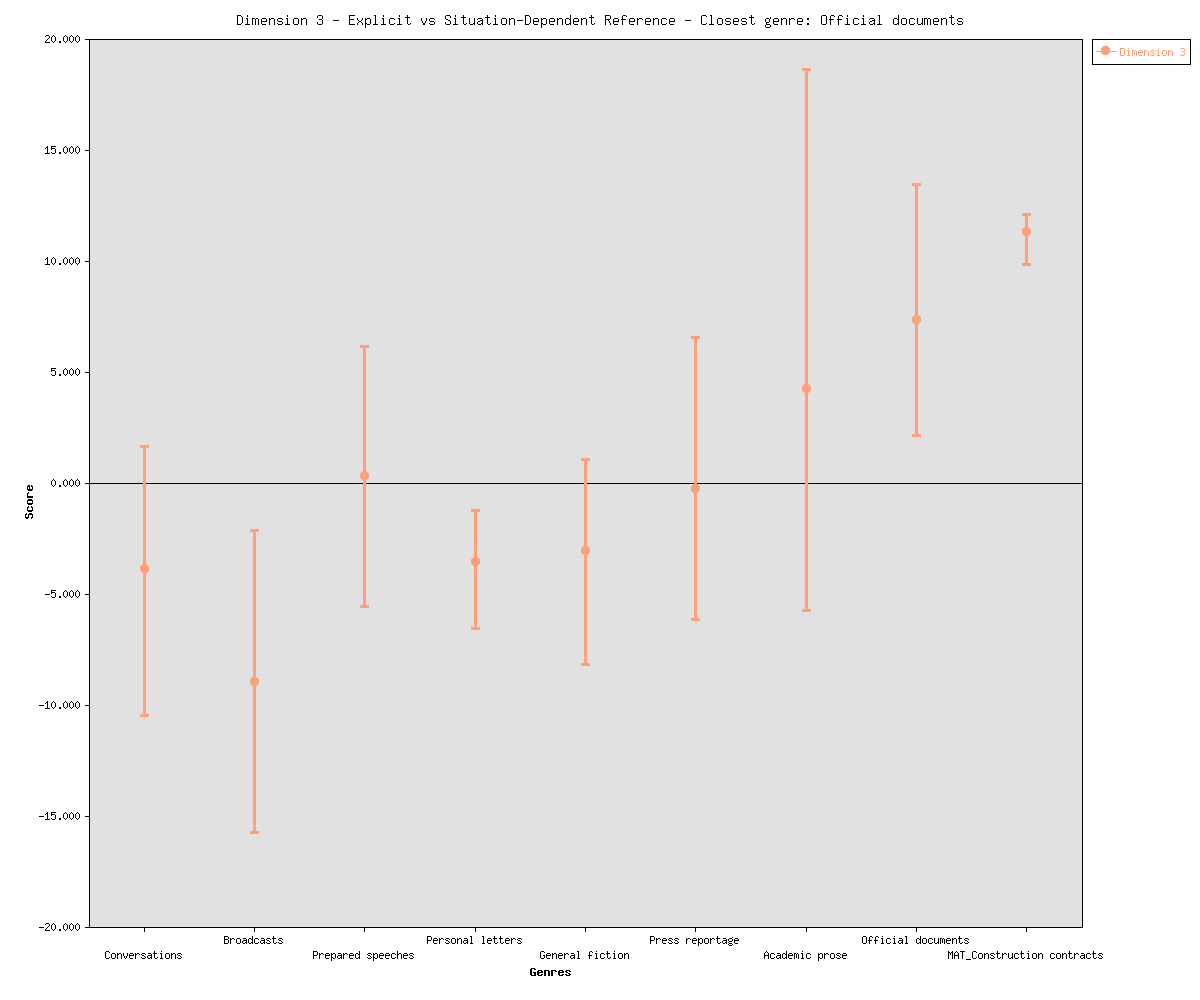

On the dimension of, the score was 11.3. It is a high score suggesting that the language of CC does not depend on the context to realize their communicative purposes and that many nominalizations are rich in CC. We can see in Figure 4 that CC are closest to official documents in generic features, sharing many similarities with academic prose. Such features are the results of the nature of CC. Usually, to make sure the smooth implementation of all the measures, CC are usually drafted beforehand. In this sense, CC need to go beyond the contexts that they are in use and embrace a bigger picture. This practice in the professional domain makes them extricate themselves from the boundaries of the immediate context in the language respect. Furthermore, being independent of the context further proves that CC are objective and fair in nature.

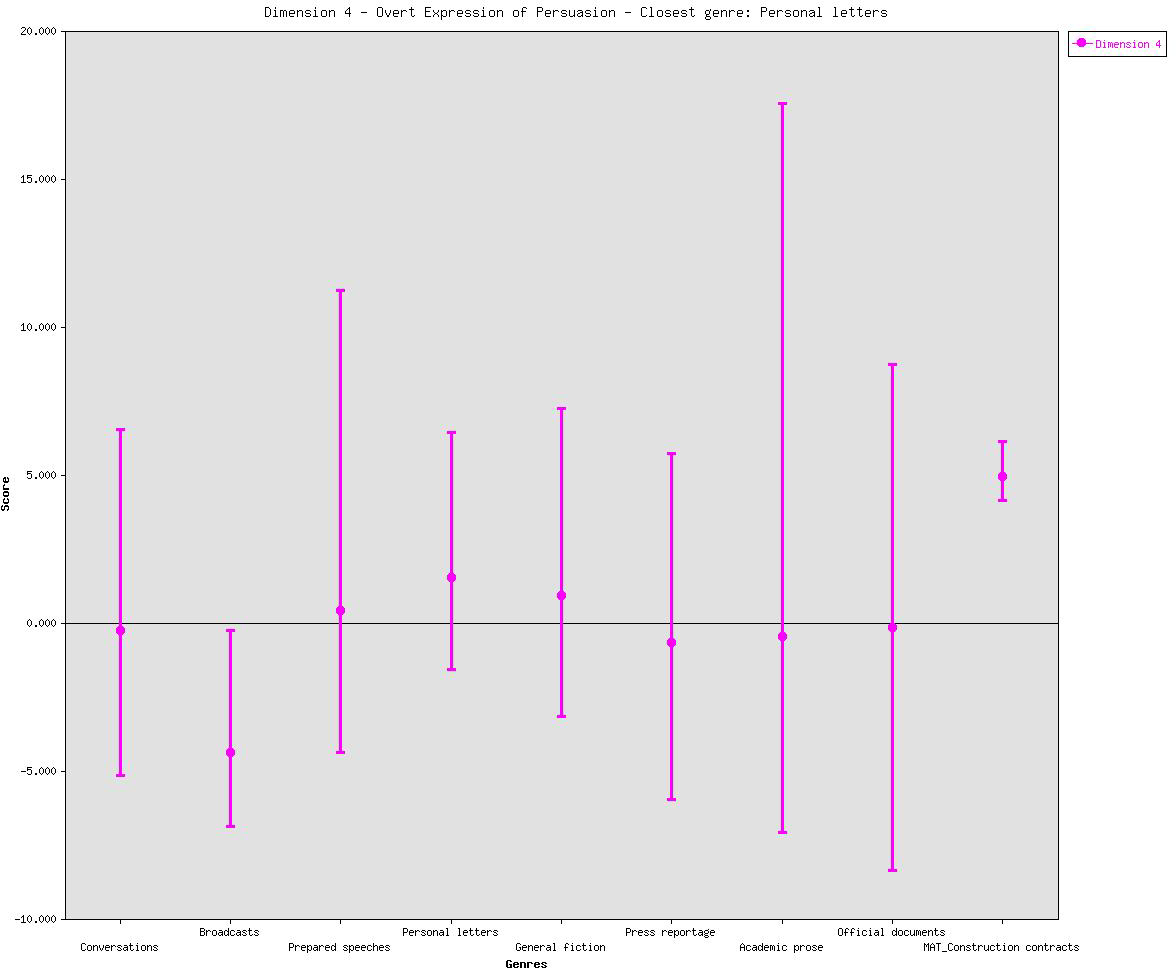

On Dimension 4, Overt Expression of Persuasion, as shown in Figure 5, CC had a score of 4.92. It indicates that stakeholders’ ideas and their evaluation or judgment toward given issues are revealed in CC

(Nini, 2019), making them share most similarities with personal letters. This generic feature can be interpreted through the nature of CC, the documents that are agreed upon by all the stakeholders in the same construction projects. They are built on the consensus of relevant parties and attempt to convince the readers of the credibility of the document (Biber, 1988). To reach that end,, andare usually used (Biber, 1988; Nini, 2019). That can be seen in Example 6. As revealed in this example, viewpoint and assessment are expressly presented. Furthermore,,andmake the text more of persuasion.

Example 6

If Contractor fails to clean up as provided in this Article 3.15 or elsewhere in the Contract Documents, Owner may do so, and Owner shall be entitled to reimbursement from Contractor. (Excerpt from Contract4)

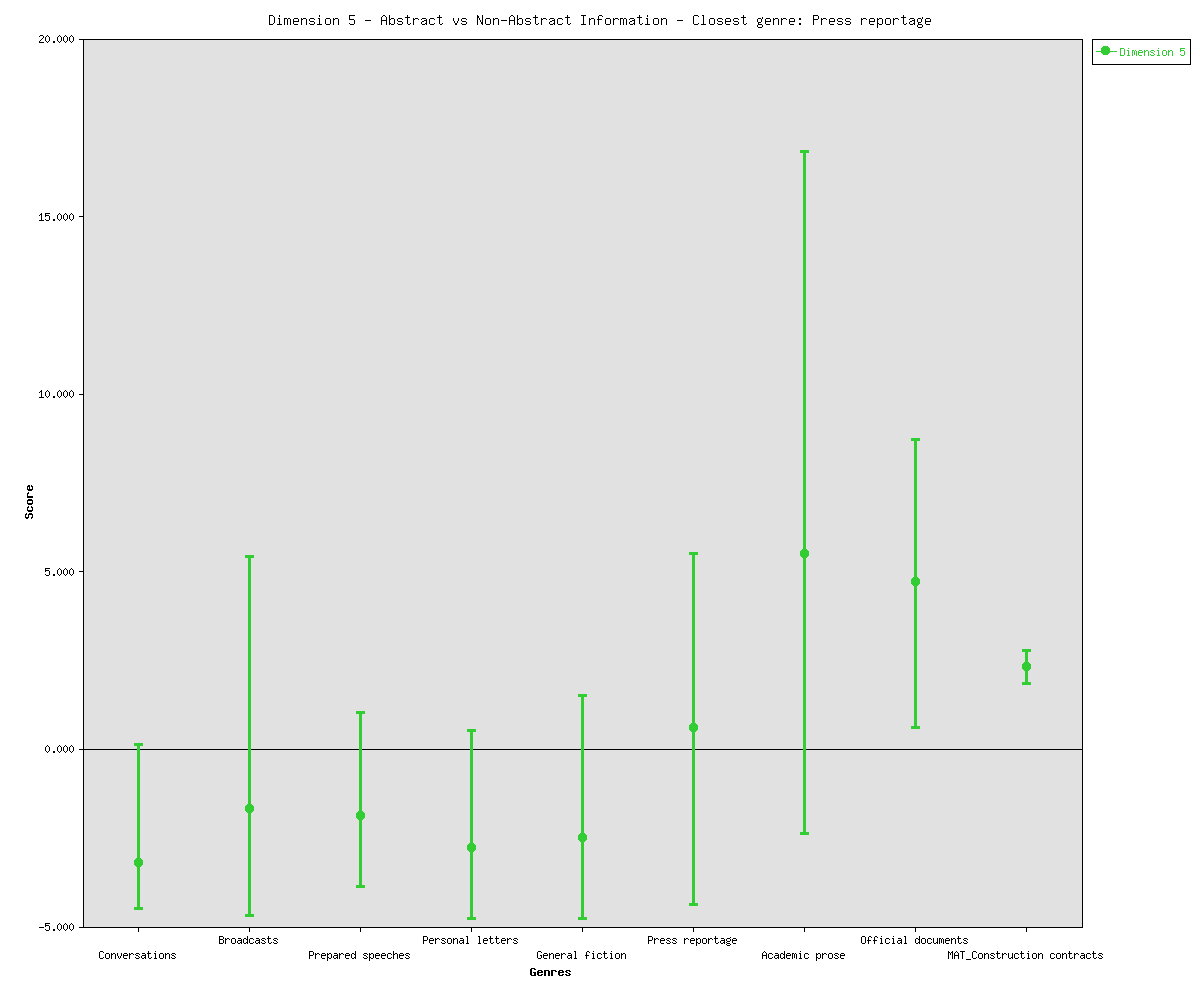

On Dimension 5, Abstract vs. Non-Abstract Information, the CC have a score of 2.3, as revealed in Figure 6. Though the score is not high, it still indicates that CC provide information in a technical and formal manner. Similar to the feature of being formal, being technical is also a feature of CC. This is because CC are used to deal with issues concerning technical issues, i.e., machines, construction materials, maintenance of buildings, insurance, and other legal or business issues (Wang & Yang, 2016). As can be seen from Example 7, the technical nature is revealed through words like defend, indemnify, subsidiaries, divisions, parent companies, affiliate companies, joint ventures, and so on. Because details need to be elaborated in CC, they are not so abstract in sentence patterns as in academic genres. Most sentences in CC are long but simple in structure, displaying information in linear ways (Cheng, 2009).

Example 7

To the fullest extent permitted by applicable law, Contractor shall defend, indemnify and hold harmless Owner its subsidiaries, divisions, parent companies, affiliated companies, joint ventures, successors and assigns, and any of its or their officers, directors, employees, personnel, partners and members, and each and all of them --- claims, demands, actions, lawsuits, investigations, actual or threatened legal, --- (Excerpt from Contract 2)

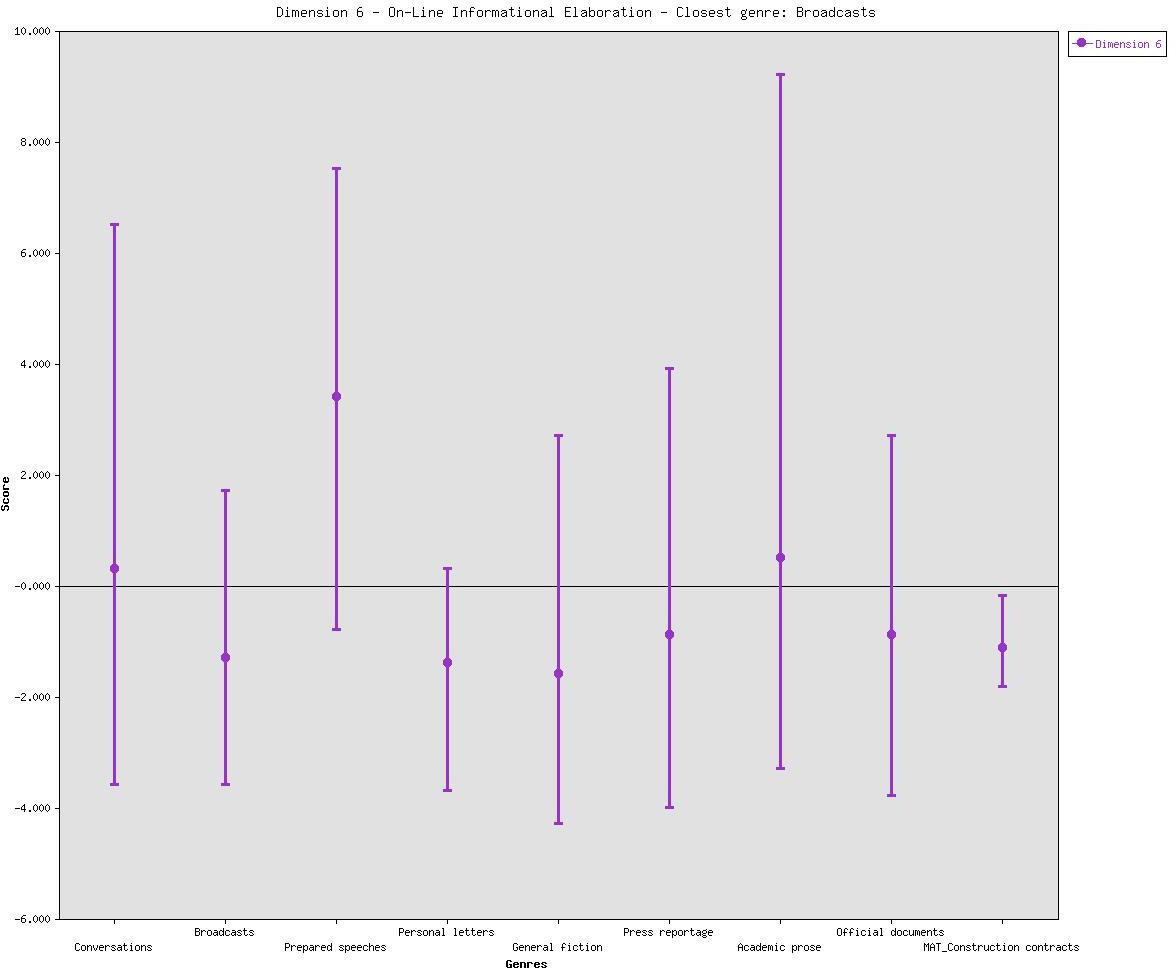

On Dimension 6, which aims to reveal the target genres’ timeliness, the stress is put on the high informational nature with strict real-time constraints. As can be seen from Figure 7, the score of -1.12 suggests that CC belong to the genre that does not possess a real-time-oriented nature. The reason is that CC are geared toward what has yet to happen in most cases. In brief, they are more of a prediction. Furthermore, a low score means the texts are non-colloquial in language style, proving that the language in CC is geared toward written documents.

Conclusion

From the above analysis, nouns and nominalization, propositional phrases, and attributive adjectives are quite frequently used in CC to serve specific communicative purposes. The study also finds that,,,,, andare scarcely employed for the fact that they are not suitable for the communicative purposes of CC. As for the reasons for the language features found in this study, professional practices and professional cultures have a significant influence on them, directly or indirectly. When it comes to the overall generic features of the CC used in this corpus, it can be found that CC are informational, non-narrative and expository, context-independent, persuasive, abstract, and written in nature. These features further make CC formal in style, explicit in communicative purposes, objective in stance, and authoritative in position. The language features are not out of thin air but are the results of the evolution of professional practices and professional cultures.

Acknowledgement

The authors of this paper extend their heartfelt gratitude to Dr. Abdul Rahim bin Haji Salam, Dr. Hanita Hassan, and Shanti Chandran a/p Sandaran for their great enlightenment and guidance. Our appreciation also goes to the examiners of this paper for their patience and insightful instructions. We also want to thank the organizers and all those concerned for providing an excellent platform and high-quality service. The current work was supported by Hebei Education Department [Grant number: 2021GJJG329]

References

Bhatia, V. (1993). Analysing genre: Language use in professional settings. Longman.

Bhatia, V. (2004). Worlds of written discourse: A genre-based view. Bloomsbury.

Bhatia, V. K. (2008). Genre analysis, ESP and professional practice. English for Specific Purposes, 27(2), 161-174.

Bhatia, V. (2017). Critical genre analysis: Investigating interdiscursive performance in professional practice. Routledge.

Biber, D. (1988). Variation across speech and writing. Cambridge University Press.

Biber, D., & Conrad, S. (2019). Register, Genre, and Style. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108686136

Biber, D., Connor, U., & Upton, T. A. (2007). Discourse on the Move: Using corpus analysis to describe discourse structure. John Benjamins Pub. Co.

Candlin, N., & Maley, Y. (1997). Intertextuality and interdiscursivity in the discourse of alternative. Cambridge University Press.

Carlo, G. (2015). Diachronic and synchronic aspects of legal English. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Cheng, H. (2009). A stylistic analysis of English contract for international engineering projects. Taiyuan University of Technology.

Elkhayat, Y., & Marzouk, M. (2022). Selecting feasible standard form of construction contracts using text analysis. Advanced Engineering Informatics, 52, 101569.

Feng, D. W. (2019). Interdiscursivity, social media and marketized university discourse: A genre analysis of universities' recruitment posts on WeChat. Journal of Pragmatics, 143, 121-134.

Flowerdew, J. (2015). John Swales's approach to pedagogy in Genre Analysis: A perspective from 25 years on. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 19, 102-112.

Halliday, M., & Matthiessen, M. (2004). An introduction to functional grammar (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press Inc.

Han, P., & He, H. (2012). The Relation of Abstract and Introduction of Research Articles under the Scope of Critical Genre Analysis. Foreign Language and Foreign Language Teaching, 1, 53–57.

Hyland, K. (2004). Genre and second language writing. University of Michigan Press.

Hyland, K. (2005). Metadiscourse: Exploring interaction in writing. Continuum.

Hyon, S. (2018). Introducing genre and English for specific purposes (1st ed.). Routledge.

Li, S., He, B., & Kong, J. (2020). Legal risk of construction contract. China Architecture Publishing & Media co., Ltd.

Liu, C. (2018). A contrastive study of generic intertextuality on the disputes over South China Sea between Chinese and American Media — Take People’s Daily and New York Times for Example. Nanjing Normal University.

Liu, J. (2008). Analysis on FIDIC contract features in terms of functional stylistics. Southwestern University of Finance and Economics.

Lv, W. (2015). International project contract management. Chemical Industry Press.

Martin, J. R. (1985). Process and text: Two aspects of human semiosis. In J. D. Benson, & W. S. Grevanes, (Eds.), Systemic Perspectives on Discourse: Selected theoretical papers from the 9th International Systemic Workshop. Norwood, N. J. Ablex (Advances in Discourse Processes 15).

McNamara, A. J., & Sepasgozar, S. M. E. (2021). Intelligent contract adoption in the construction industry: Concept development. Automation in Construction, 122, 103452.

Murdoch, J. R., & Hughes, W. (2008). Construction contracts: Law and management (4th ed.). Taylor & Francis.

National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2022). Statistical bulletin of the people's Republic of China in 2021. National Bureau of Statistics of China.

Nie, M. (2021). Analysis of Interdiscursivity in social media advertising discourse from the perspective of CGA: A case study on the videos released on Apple Youtube Channel. Guangdong University of Foreign Studies.

Ning, X., & Wu, W. (2019). English for project management. China Machine Press.

Nini, A. (2019). The multi-dimensional analysis tagger. In T. Berber Sardinha, & M. Veirano Pinto, (Eds.), Multi-Dimensional Analysis: Research Methods and Current Issues (pp. 67-94). Bloomsbury Academic.

Orts, M. Á. (2015). Power and Complexity in Legal Genres: Unveiling Insurance Policies and Arbitration Rules. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law - Revue internationale de Sémiotique juridique, 28(3), 485-505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-015-9429-6

Qi, Y. (2004). Contract and contract English. Zhengjiang University Press.

Rasmussen, K. W., & Engberg, J. (2017). Genre Analysis of Legal Discourse. HERMES - Journal of Language and Communication in Business, 12(22), 113. https://doi.org/10.7146/hjlcb.v12i22.25497

Swales, J. (1990). Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings. Cambridge University Press.

Swales, J. (2004). Research genres: Explorations and applications. Cambridge University Press.

Sweet, J., Schneier, M. M., & Wentz, B. (2015). Construction law for design professionals, construction managers, and contractors. Cengage Learning.

Tessuto, G. (2012). Investigating English legal genres in academic and professional contexts. Cambridge Scholars.

Wang, J., & Yang, G. (2016). Contracts for construction projects. Lawpress, China.

Wang, M., & Li, W. (2016). English for International Engineering Management Practice. China Communications Press Co., Ltd.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 September 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-964-1

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

7

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-929

Subjects

Language, education, literature, linguistics

Cite this article as:

Bian, Y., & Ibrahim, N. M. (2023). Language Features of Construction Contracts From the Lens of Genre Analysis. In M. Rahim, A. A. Ab Aziz, I. Saja @ Mearaj, N. A. Kamarudin, O. L. Chong, N. Zaini, A. Bidin, N. Mohamad Ayob, Z. Mohd Sulaiman, Y. S. Chan, & N. H. M. Saad (Eds.), Embracing Change: Emancipating the Landscape of Research in Linguistic, Language and Literature, vol 7. European Proceedings of Educational Sciences (pp. 203-218). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.23097.19