Abstract

Distance learning (DL) experience during emergency, made by schools during last years, has highlighted several implications in the learning path of students. The literature has focused a complexity of factors that can influence the learning outcomes of students during DL and has pointed out many obstacles in maintaining continuity in teaching and ensuring the active involvement of all students. The researches have underline the importance of embracing a broader view and consider several elements that can be significant in determining the learning experiences of students in a period of crisis. These considerations are particular significant for students in vulnerable conditions, who are those who have been most affected by the impact of DL in recent years. Starting from these assumptions, this work explores the students' point of view regards their experience during DL and their perception about the difficulties encountered. The survey is aimed to better understand, according to the student’s perspective, the elements that have supported their learning paths, and those which has instead impeded their participation. The article proposes a critical reflection on the factors that can support students, especially those who are more at risk of failure.

Keywords: COVID-19, distance learning, educational design, student’s perception

Introduction

The distance learning (DL) during the covid-19 emergency, has represented a tool to ensure continuity in learning paths during pandemic era. The experience made by schools in recent years has highlighted critical aspects and pointed reflections towards the implications of the DL. The research has highlighted on the one hand, positive aspects of online teaching, such as the promotion of greater autonomy by students, the development of greater competence in the use of technologies; on the other hand negative aspects, such as an inequality in the distribution of resources, a low digital competence of a part of teachers, but also profound implications in the emotional and social wellbeing of students (Dube, 2020; Frenette et al., 2020; Lucisano, 2020; Moss et al., 2020).

The data provided by Unesco undoubtedly highlight a global evolution of the situation of school closures from the beginning of the pandemic to today: in April 2020, distance learning programs were adopted for 91.3% of students. (for a total of 1,598,099,008 students around the world outside of schools); 194 countries have in fact closed their schools and activated distance learning. In the following months, a partial return of students to school was observed, alternating with periods of distance learning; to date, the data show that distance learning affects 2.8% of total enrolled learners (43,518,726 students) and 6 country-wide closures. Therefore, the situation is now changed, compared to that observed at the beginning of the pandemic, even if the measures to contrast Covid-19 still provide for alternating between teaching in presence and on line learning in case of a critical situation. Distance learning therefore still represents a method adopted by schools and has become an integral part of the students' academic career in order to ensure their educational continuity.

The Covid-19 pandemic has determined an emergency condition that the community and schools have had to face in a sudden and unscheduled manner. Schools had to adopt extraordinary measures to deal with the emergency and even the return of the students in the class, was determined by continuous requests for adjustment. A condition in constant evolution, which has certainly determined a perception of instability, has required great flexibility, but has also determined a profound impact on the emotional and psychological well-being of students.

As pointed out by Moss et al. (2020), researches have focused their attention on different aspects of learning during the pandemic. Part of the literature has analyzed what students have lost in terms of learning during the DL. These researches have tried to quantify the damage, the learning that was missed, emphasizing the need to recover. Focusing on learning loss means placing a lot of emphasis on results, on student performance and conceptualize learning from the point of view of outcome. Another part of literature has instead focused attention on the responses given by schools during closures, highlighting the set of factors that can be significant in determining the learning experiences of students in a period of crisis. This line of research embraces a broader view and therefore considers the complexity of the elements that can influence the learning path. These considerations are particularly significant, especially for students in vulnerable conditions, who are those who have been most affected by the impact of DL in recent years (Brändle & Albers 2020; Cullinane & Montacute, 2020; Girelli, 2020; Lucisano, 2020). In fact, this segment of population has worse access to technologies, in many cases they do not have adequate devices, but they also show a greater discontinuity in following the lessons, all elements that risks to accentuate the educational inequality.

Digital inequality

The digital skills of young people are still not as well acquired as one might suppose. In fact, although the use of the internet and its applications has become a deep-rooted and widespread habit even among the very young, this familiarity with the digital world does not always translate into a real competence and mastery in the use of IT tools (Beckman et al., 2018).

Not all students are actually "digital natives": in fact, they are not always so expert in the use of new technologies, in accessing content on internet, but also in being able to filter information knowing how to distinguish between reliable source or not.

Students should acquire the adequate skills to access technologies effectively to achieve their educational goals, but what is meant by "adequate digital access"? Several questions can be raised in this regard: the choice of the most suitable device (is an individual PC necessary? Is it possible to think of shared devices? Is a mobile phone sufficient?); the technical specifications necessary to use a device; the differentiation of skills based on age; the use of technology at home (with the consequent need to define working spaces and times).

Inequality in access to digital technology is not overcome only in relation to access issues, but by rethinking broader inclusion strategies and policies, which support in more holistic terms the educational pathways of the most fragile sections of the population. In fact, technology cannot be considered simply as a tool disconnected from cultural and social contexts: it should be considered a cultural artefact, inserted within contextual and temporal dynamics that define its use.

Use of devices at home

Distance learning has certainly changed the spaces and times of education, redefining the boundaries of separation between personal and domestic space and work and learning space. DL has made the time spent on learning much more flexible, requiring a re-edition of one's personal organization. Certainly there is a criticality in maintaining a separation boundary between the connection and disconnection times from the devices, which become more fluid and less distinct, with the risk of incurring a temporal overexposure to the network. Therefore, if on the one hand the use of digital devices in the home has allowed continuity in the training courses of students during pandemic, on the other hand, critical issues and alterations in the organization of spaces and life times are raised (Alirezabeigi et al., 2020). The risk is therefore of a hyperconnection: merging the study space with the personal one, effectively losing the routines that begin to become less meaningful.

In a study by Moss et al. (2020), it is highlighted how important it is to consider various aspects related to the use of distance learning in the home environment, especially with regard to the most fragile segments of the school population. According to the researchers, teachers have gained greater awareness, through the DL experience, of the living conditions’ impact on most vulnerable students learning. In the most disadvantaged situations, the success of learning at home depends heavily on the support networks that can be activated for families in the community. It is important to adapt homework and distance learning to the constraints that home learning places required.

We should take into account the context in which distance learning takes place, how it is inserted in a different family dynamic, in which parents must be able to juggle work from home, family and learning needs of their children. It therefore emerges that the context in which learning takes place triggers specific requests: learning at home cannot replicate the dynamics and routines of a school environment. According to the researchers, therefore, focusing the problem of distance learning only on what it was not possible to achieve in terms of educational contents and consequently on how to recover them, is an understatement. Instead, it is a question of focusing attention on broader aspects of the problem, such as regaining a school routine, involving students in social relationships with their peers, working for the well-being of pupils. The school should place the centrality of students as primary to better plan targeted and meaningful learning. Therefore, it is not just a matter planning a recovery of the didactics that has been lost, but it concerns to think about a long-term path that analyzes the needs of learners in a broad way.

Problem Statement

The research was developed within the FAMI IMPACT FVG project (Qualification of the school system in multicultural contexts, also through actions to contrast early school leaving) (FAMI-IMPACT FVG 2018-2020 project, funded from 2014-2020 - OS2 Migration and Integration Asylum Fund. The project is carried out in collaboration with the University of Trieste and the University of Udine with the proponent FVG region, to promote research and teacher training to contrast early school leaving, in particular in foreign students.) . The project aimed to analyze the risk factors related to school failure in students in secondary schools and promote experimentation to contrast early school leaving.

Research Questions

For the purposes of this work, we explore the research questions related to DL:

Which digital tools did the students use during the DL?

How students had experienced the on line lessons?

How the online materials provided by the teachers were used by the students?

What are the aspects of difference and similarity between face-to-face and on line lessons?

Purpose of the Study

This work aims to explore the perception of students regarding distance learning (DL) during the period of lockdown.

Research Methods

Sample

The inquiry involved a total of 172 students in the second level of secondary school, who answered an online questionnaire. The survey was aimed to students under the age of 18th (average age = 16, 27; SD = 0.74; female students = 72,7%; male students = 22,7%; undeclared sex =4,7%).

Measure

The questionnaire was divided into different sections and made up of closed items (on a likert scale from 0 to 4) and open questions. The survey was distributed at the end of a period of lockdown, during which the school adopted the distance learning.

The questionnaire was structured to investigate different aspects involved in the learning process during DL; in this contribution we focus on the answers given to following questions:

Which kind of tool do you utilize to follow on line lessons?

How easy is it for you to follow the lessons at distance? Could you explain the reason of your answer?

How easy is it for you to use the materials given by the teachers? Could you explain the reason of your answer?

Do you think that the on line lessons are similar to lessons in presence? Could you explain the reason of your answer?

Findings

Tool used to follow the lessons

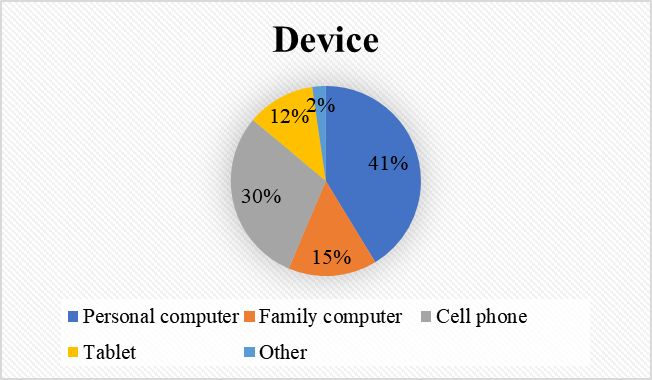

Most of the students use a personal computer (41%) or cell phone (30%) to follow lessons at distance (Figure 1).

Easiness in follow the lessons at distance

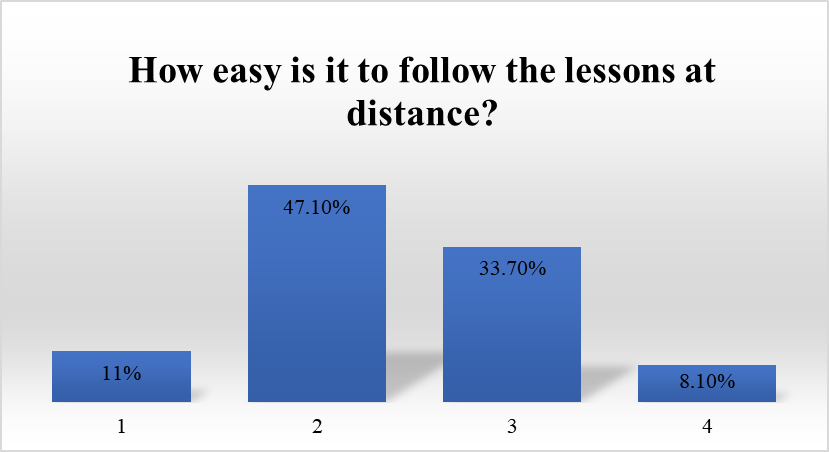

For most students, it is not easy to follow the lessons at distance (58%; Figure 2)

Students who declare that it is not easy to follow the lessons at distance, identify the following categories of responses as their main reasons:

lack of attention

“For me it is a bit difficult to follow the lessons at a distance because after a while I get lost and I don't concentrate anymore, sometimes I try with all my strength to stay focused but, above all, I prefer to go to school”.

“With distance learning the lessons are boring, not very stimulating and, among other things, having many things available at home, you are easily distracted”.

technical problems

“For various problems it is sometimes difficult to follow the lessons, for example: the connection, problems with the microphone and the camera, etc”.

difficulties in comprehension

“For me it is very difficult to understand the explanations at distance”

Other students identify some positive aspects that facilitate learning:

good solution in time of emergency

“For me, following the lessons in general is not difficult, of course, in presence it is much better but for the situation in which we are living, DL can be a good solution if used well, and I am happy with it”.

“It was initially difficult to follow the lessons, as none of the class knew what to do. And then when we hit the pandemic, I started using the computer more often to do my homework. And then I learned how to use it more often, learning how to use it well”.

felling more relax; quietness

“I feel more relaxed and therefore I am able to follow better and more carefully”

more comfort

“It's comfortable for me so I'm calmer in the morning”.

Easiness in using the materials given by teachers

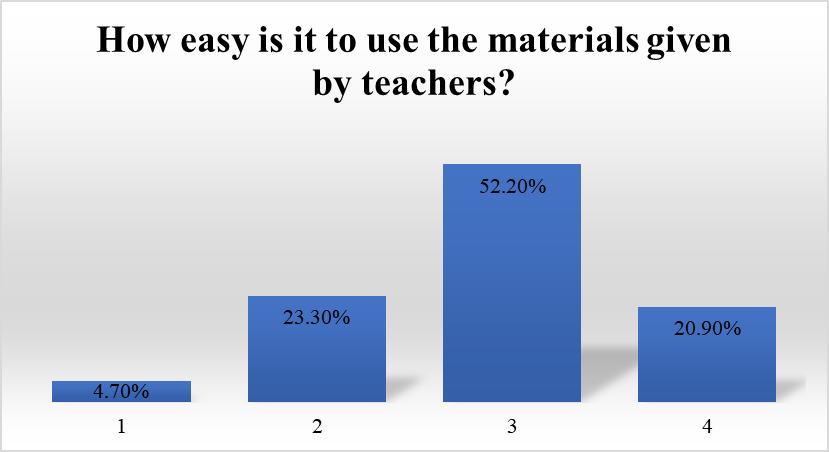

For most students, it is easy to use the materials given by teachers (73%; Figure 3)

Most students declare to use easily the materials:

good organization on the platform

“It's easy to use teachers' materials because everything is in order on classroom”

“It is quite easy to use the material that they deliver to us on classroom because at any time we can find them and also indicate the expiration dates”

sharing documents

“Using the Google apps (classroom, drive, sheets, presentations ...) it is very easy to share files for study and homework”.

different types of materials

“For some subjects it is easy because some teachers attach cards or videos, useful to study”

Students who declare that it is not easy to use the materials given by teachers at distance, identify the following categories of responses as their main reasons:

technical problems

“I had a pc last year, which broken and they never returned it to me…. and now I have difficulties in follow the lessons”

difficulties in understanding the instructions

“Sometimes I don't understand the materials that are assigned to us, because the instructions are not clear”.

Similarity between lessons in presence and at distance

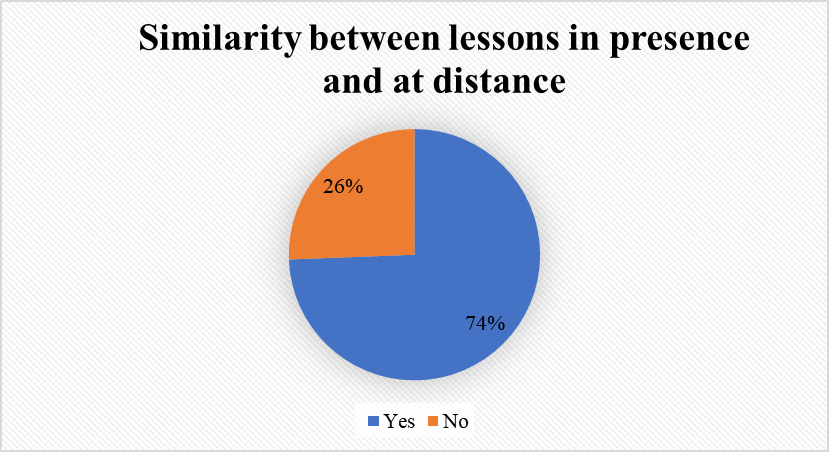

For most students, distance learning is not similar to lessons at school (74%; figure 4),

The students identify the following reasons:

Lack of relationship

“Because there is no contact with the professors”

“They are different because at school you can confront yourself directly instead at home you have to wait for an answer in the emails”

Lack of routine

"There is a kind of routine in school teaching that gives you a specific feeling”

“In distance learning you do not follow any routine Eg. I usually (in DaD) wake up at 7:30 I have a coffee or I drink it later when I am in front of the video "

Lack of collaboration

“In the classroom there is more collaboration and discussion; while in dad the teacher explains and no one collaborates”.

“They are not similar at all, at least at school we are all together, we do the work in groups, we can also compare. It is also easy to follow the lessons”

26% of students do not find differences:

Similarity in teacher explanation

“The professors are able to explain the program, and as in the presence”.

Similarity in the structure of lessons

“They are very similar. The only difference is that one is in the classroom and the other is via a screen”.

“The only difference is that in class everyone is facing the teacher and in the video lesson you have everyone as if they were in front of you”.

Discussion

The results show that not all students have a personal PC available to follow distance lessons; many of them use their mobile phones or other devices, sometimes shared with their families. These technical difficulties are one of the aspects that negatively affect the opportunity to participate to the learning activates. In fact, the students identified one of major obstacle in DL the good functioning of the technological devices and the fact of having them available: connection difficulties, devices that do not work well, reduced screens, inadequate audio are factors that compromise the conditions of students’ participation.

Other factors identified as critical, emerges the difficulty in maintaining attention, in managing the sources of distraction, in understanding the contents of the lessons. For students, therefore, it seems to be much more complex to manage their cognitive resources in a less structured context (such as the home environment), where the routines are not well defined and the distraction factors much higher. On the other hand, a group of students consider the DL more functional: in the distance learning they better control the emotional aspects and face the proposed activities in a more relaxed way.

Most students recognize the advantages of using materials through distance learning, attributed to the functionality of the platforms and to organizational aspects. The use of online platforms creates a sharing space where all materials are easily available and at the same time facilitates the organization of tasks and timing. Even the use of tools or different types of materials (such as videos, ppt, cards), is considered a positive aspect for learning that facilitated the students. On the other hand, difficulties in understanding the instructions and how to use the proposed materials are critical aspects reported by the students.

The students believe that there are profound differences between lessons in presence or at distance, due in particular to: difficulty in establish relationship with teachers and peers; lack of teamwork; difficulty in setting up a well-defined routine. Therefore, the collaborative learning seems to be insufficiently used as strategy during DL. In fact, students declare that the distance learning particularly affected the opportunities of interaction and of collaborate in groups.

Finally, some students do not find particular differences between the two methods: they identify the same structure of the lesson (mostly classroom-taught lesson), and the same methods of explanation by the teachers. Therefore, some lessons during DL does not differ from the modalities in presence, and maintain a traditional structure, with less involvement of the students.

Conclusion

The effects of the pandemic are certainly heavier for the more fragile social communities that suffer the impact in a more significant way. In this risk scenario, the school plays a decisive role in addressing the complex needs of the most vulnerable students. The school therefore represents a pivotal point, a protective element that becomes decisive in historical periods of economic crisis and fatigue. A resilient school system represents a support for the community and for families: it is therefore not just a place to learn, it is much more.

The learning that takes place through the digital medium has its own characteristics that make it unique with respect to the forms of teaching that take place in presence. Although the value of technologies as a learning tool is recognized, it is clear that their use is strictly linked to methodological-didactic choices, without which it is not possible to ensure the effectiveness of the proposed actions.

It is therefore a question of acquiring specific teaching planning skills that make the most of the potential offered by digital and that at the same time guarantee equal learning opportunities for all. Involving students who are more difficult to achieve through the DL is a challenging objective: it is a question of making them active participants, considering them as resources and at the same time empowering them (Batini & Benvenuto, 2016).

Supporting the learning paths especially of students that are difficult to reach becomes more crucial than ever in distance learning, as the difficulties that emerge place this segment of the population even more at risk of failure. Planning of activities becomes relevant in order to provide inclusive teaching that is able to respond to complex educational needs, even at a distance. Therefore, the training of teachers should guide them, also through action research paths, to experiment learning paths that are suitable for the digital world. It is about supporting teachers in their professional training path, in order to acquire specific methodological skills useful to plan their own action in virtual classrooms.

References

Alirezabeigi, S., Masschelein, J., & Decuypere, M. (2020). Investigating digital doings through breakdowns: a sociomaterial ethnography of a Bring Your Own Device school. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(2), 193-207. DOI:

Batini, F., & Benvenuto, G. (2016). Le parole disperse. La voce degli studenti drop-out e la ricerca etnografica in pedagogia [Student drop-out voice and ethnographic research in education], in G. Szpunar, P. Sposetti, & A. Sanzo (Eds.), Narrazione e educazione. Nuova Cultura.

Beckman, K., Apps, T., Bennett, S., & Lockyer, L. (2018). Conceptualising Technology Practice in Education Using Bourdieu’s Sociology. Learning, Media and Technology, 43(2), 197–210. DOI:

Brändle, T., & Albers, A. (2020). Results of an online survey of parents, educators and students in Hamburg. Retrieved on 29 May to 7 June 2020, from https://www.hamburg.de/contentblob/14044438/e769acae29010424c56d88f4763823a2/data/bliz-results-report.pdf

Cullinane, C., & Montacute, R. (2020). COVID-19 and Social Mobility. Impact Brief #1: School Shutdown. https://www.suttontrust.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/School-Shutdown-Covid-19.pdf

Dube, B. (2020). Rural Online Learning in the Context of COVID-19 in South Africa: Evoking an Inclusive Education Approach. Multidisciplinary Journal of Educational Research, 10(2), 135-157. DOI:

Frenette, M., Frank, K., & Deng, Z. (2020). School Closures and the Online Preparedness of Children during the COVID-19 Pandemic, In Statistics Canada, Economic Insights, 11-626-X(103), 1-8.

Girelli, C. (2020). La scuola e la didattica a distanza nell’emergenza Covid-19 [School and distance learning during the Covid-19 emergency]. First results of the national research conducted by SIRD (Italian Society for Educational Research) in collaboration with teachers' associations (AIMC, CIDI, FNISM, MCE, SALTAMURI, UCIIM). RicercAzione, 12(1), 203-208.

Lucisano, P. (2020). Fare ricerca con gli insegnanti. I primi risultati dell’indagine nazionale SIRD “Per un confronto sulle modalità di didattica a distanza adottate nelle scuole italiane nel periodo di emergenza COVID-19” [Research with teachers. The first results of the SIRD national survey "For a comparison on the distance learning methods adopted in Italian schools during the COVID-19 emergency period"]. Lifelong Lifewide Learning, 16(36), 3-25.

Moss, G., Allen, R., Bradbury, A., Duncan, S., Harmey, S., & Levy, R. (2020). Primary teachers' experience of the COVID-19 lockdown–Eight key messages for policymakers going forward. UCL Institute of Education.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 May 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-962-7

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

6

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-710

Subjects

Education, reflection, development

Cite this article as:

Bembich, C. (2023). Distance Learning Experience During Emergency: Perception Of Students And Teaching Implication. In I. Albulescu, & C. Stan (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development - ERD 2022, vol 6. European Proceedings of Educational Sciences (pp. 295-305). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.23056.27