Abstract

Weaving a tapestry that merely reflects the cultural landscape of the school is an incentive, yet from demographics to cultural competence and, ultimately, to a successful academic environment there are continuous, all-encompassing cross-cultural interactions. Aware of the need to acknowledge the cultural diversity of a school, the scale ”Measuring Cultural Awareness in Nursing Students” was translated and adapted with the specific purpose to examine the impact of the demographics in a high school in the Danube Gorge, that educates students coming from five ethnic minority groups, out of the total seven major ethnic groups in Caraș-Severin, as recorded in the 2011 Romanian census. The research method applied was the survey conducted by means of a 5-point Likert response format questionnaire, serving as instrument, hence the 108 students per school as participants. Thus, the survey was conducted in the aforementioned school with Czech, German, Hungarian, Roma and Serbian ethnic groups, as well as in a monocultural school, where few students come from minority backgrounds. The translated scale was adapted to tailor for the requirements of high school education so that the findings enhance awareness and reveal relevant information in terms of: school environment, teachers' values, the national curriculum, language study (mother tongues of the ethnic groups), identity and cultural exchanges, recognized biases and extra-curricular activities. Only by enhancing cultural response, catering for specific needs, fostering social intelligence and nurturing growth, can cultural competence and academic excellence be attained.

Keywords: Cultural awareness, cultural competence, multicultural educational environment, school success

Introduction

The appreciation of the interculturality level that reflects the demographics of the respective area, triggers the sort of action that leads to developing academically successful schools, as well as to attaining cultural consciousness within the school community. The concept of a multicultural educational environment is applied in the case of the Banat region with its minorities and the specific ”intra-cultural dialogue” alongside the ”cultural harmonious confrontation” (Constantin & Badea, 2014, p. 3550) as a result of adaptation after numerous waves of colonisations in this border area, be those colonisations with Hungarians, Bulgarians, Czechs, Croatians, Germans, or, more specifically, the Danube Gorge Serbians, in which case, more than often the term of ”acculturation”(Bulzan, 2007, p. 139) is pronounced, with overlapping language use, customs and traditions. On the other hand, following the data collected by the National Institute of Statistics (INS) and using the minority maps provided by The Institute for Research on National Minorities (INSMP), the structure of the population in Caraș-Severin at the 2002 population census was : 88,25% Romanians, 1,75% Hungarians, 2,38% Roma, 1,88% Croatians, 1,84% Germans, 1,82% Serbians, 1,06 % Ukrainians, 0,74% Czechs and 0,28% other ethnic groups. In contrast, the 2011 population census, however, indicates a significant drop in the minority population: 82,52 % Romanian, 0,99% Hungarian, 2,46% Roma, 0,84% Ukrainian, 0,98% German, 3,42% Serbian and Croatian and 0,52% Czech, with effects on schools and the local communities. Faced with the abundance of evidence regarding the multicultural population of the Danube Gorge, as well as the existence of studies on the intercultural aspect of a region described also as ”typical interculturality” (Narai, 2012, p. 384), a deep need for awareness within the educational landscape arises. Taking the terminology clarifications a step further, acknowledgement in itself is not enough, and, therefore, the concept of cultural competence, defined primarily as ”ability to understand, appreciate and interact with people from cultures or belief systems different from one's own” (DeAngelis, 2015, p. 64) is essential in school communities. In terms of educational landscapes, The National Education Association (NEA) of the USA sets out another conceptualisation, merely as “the ability to successfully teach students who come from cultures other than your own” (Van Roekel, 2008, p. 2). School success, on the other hand, is a concept that has remained a major preoccupation for educational experts and scholars, hence the multitude of definitions and meanings, all in a climate “orchestrated by the pressures of globalization” (Costin & Roman, 2020, p. 2). Seen as “academic excellence” (Garbarino, 2008, p. 157) in early literature, where school represents “a setting primarily dedicated to cognitive development and the acquisition of knowledge and intellectual skills”, the view is shared by the guide teacherpowered.org, which, similarly, supports the idea that school success is determined by standardised tests. In an analogous way, Kalet et al. (2006, p. 921) defines school success as “a consistent awareness of and loyalty to one's own goals and priorities”. There are various spheres of defining academic excellence, but modern perspectives and pragmatic scholars shift the emphasis from “acquisition of desired knowledge” (York et al., 2015, p. 5) to abilities, sets of skills and competencies that the educational environment is supposed to equip the student with, in order to ensure a high quality life and skills for activism in the adult life. Moreover, the European Commission, in the Council Recommendation of 22nd May 2018 on key competences for life-long learning, identifies eight key competences to foster not only scholar success, but also the smooth and effortless transition to the job market, to active citizenship and civic engagement in the light of inclusive democratic values. Out of the eight competences, the multilingual one and the “Cultural awareness and expression competence” are vital to a multicultural learning environment. Westheimer and Kahne (2004, p. 239) correspondingly, emphasise the need for schools to “seek to prepare students to improve society by critically analysing and addressing social issues and injustices”. Furthermore, the much-acclaimed critical thinking, seen even as parents ‘preoccupation from early age (Coșarbă et al., 2021, p. 177) together with the adequate mindset (Dweck, 2017), cross-cultural inferences in the visible process of learning (Hattie, 2014) and a well-rounded emotional intelligence (Goleman, 2018), all these concur together, playing equal roles in educating the young for successful school and adult life.

Problem Statement

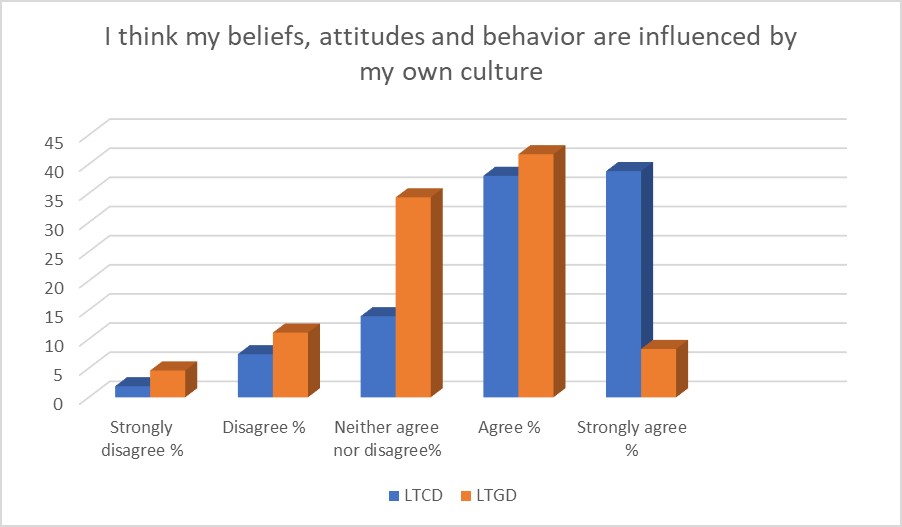

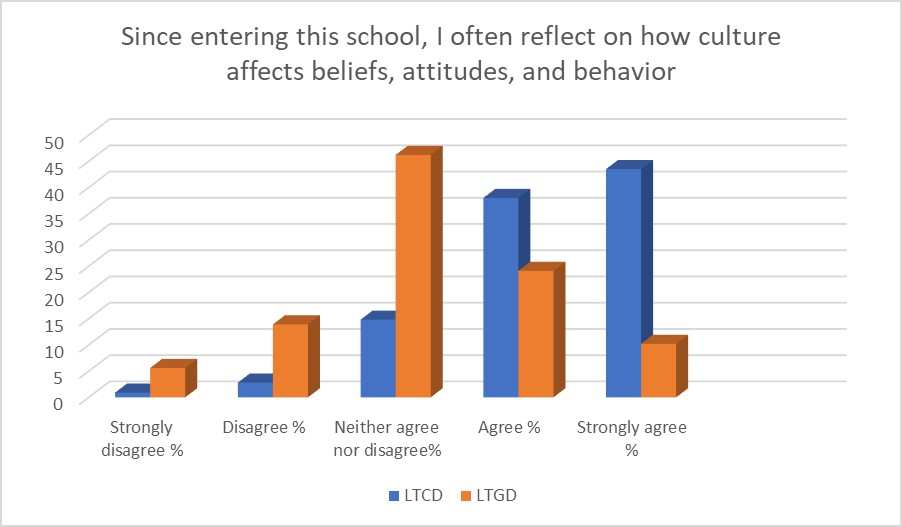

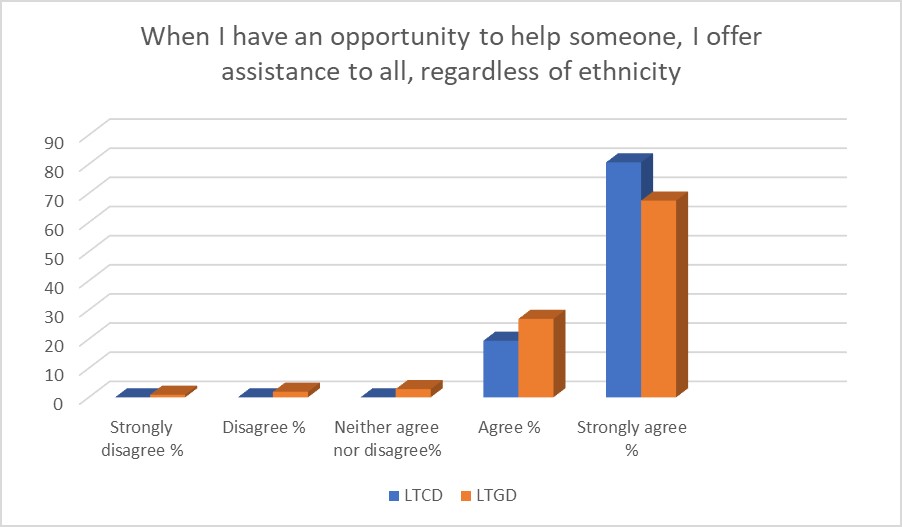

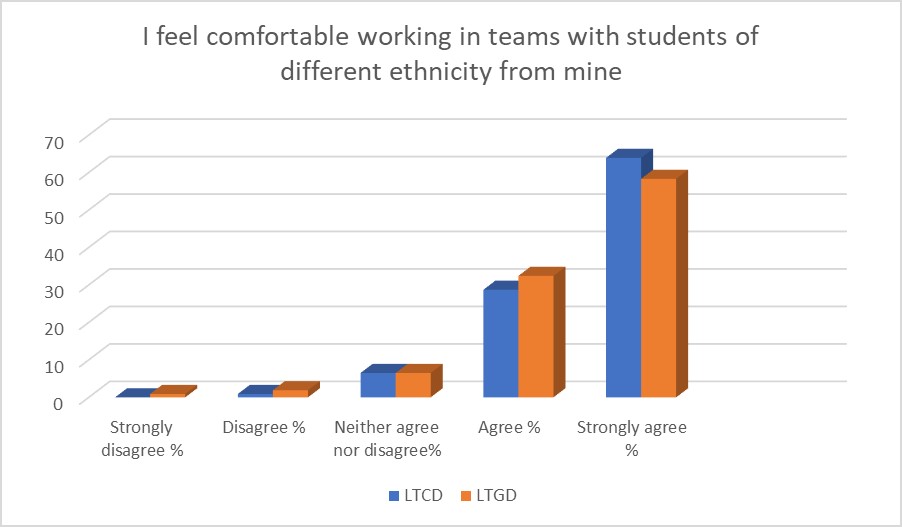

In an attempt to acknowledge the resourcefulness of the cultural diversity of a school, the translated and adapted scale “Measuring Cultural Awareness in Nursing Students” (Rew et al., 2003) was applied, examining thus the impact of the structure of the population in the only high school in the Danube Gorge, that educates students coming from five ethnic minority groups (in figures 1-15: LTCD), out of the total seven major ethnic groups in Caraș-Severin, as recorded in the 2011 Romanian census, and in another high school from Caraș-Severin county, which is, by contrast, a mainly monocultural educational environment (in figures 1-15: LTGD).

Research Questions

Is there a positive relationship between a multicultural learning environment, given the demographic structure of the school population, and school success?

What is the impact of educating culturally competent students?

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the study is to determine how a culturally aware learning environment impacts the success of its students in terms of school environment, teachers' values, the national curriculum, language study (mother tongues of the ethnic groups), identity and cultural exchanges, recognized biases and extra-curricular activities. We aimed thus to highlight the importance of developing culturally competent school communities that nurture inclusion and strive for success.

Research methods

Details on the participants

The translated and adapted questionnaire was applied to a number of 216 students, from two high schools in Caraș-Severin, one that educates students coming from five ethnic minority groups in the Danube Gorge, and the other one with no or very few ethnic minorities. The students were aged 14-18 years old and the whole process was accomplished in the course of period of 4 weeks, using a google form link.

Method and instrument

The research method applied was the survey conducted by means of a 5-point Likert response format questionnaire, serving as instrument, hence the 108 students per school as participants.

Findings

Therefore, we list below, in a contrastive approach, the results of the survey, by items, in the order they appear in the questionnaire, with explanations and figures.

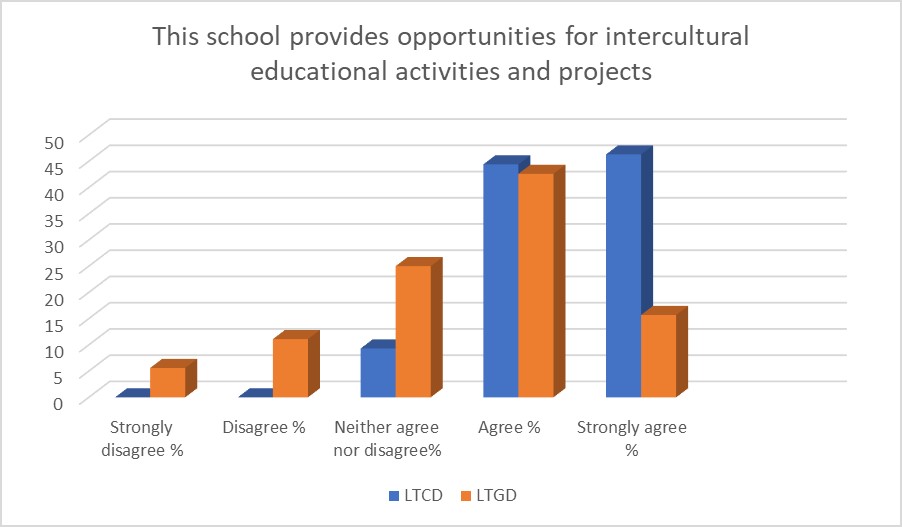

The first question, whether the school provides opportunities for intercultural educational activities and projects, aims at identifying what the content of their general school experience is, in terms of curricular and extra-curricular work. The findings show that the multicultural high school has a propotion of over 90% agreement, 46,3% of students strongly agree to the statement, respectively 44,6% agree, leaving thus only a percentage of 9,3 students who neither agree, nor disagree. By comparison, the monocultural school has a 25% of students who are neutral to the statement, as well as 11,1 percentage of students who disagree and a 5,6% with total disagreement, leaving the agreement field in a percentage of 58,3%, compared to the 90,7 one in the multicultural school. The difference of 32,4% is a clear evidence of how few intercultural opportunities are offered by the second school.

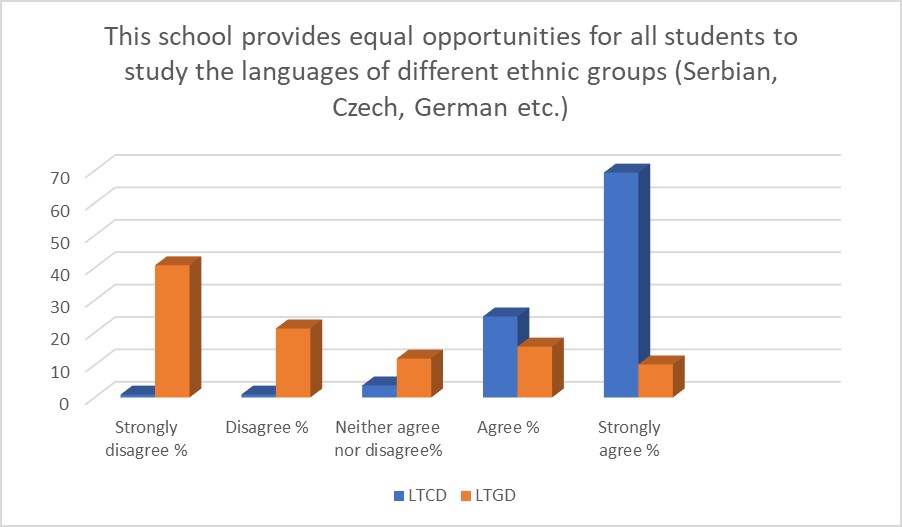

The second item is the one referring to language study, in terms of multilingualism, namely the question is whether the students are given the opportunity to study the mother tongues of the Caraș-Severin ethnic groups. Again, the percentage of agreement in the multicultural school is very high 94,4% (69,4% strongly agree and 25% agree) as mere proof that the school adequately addresses the language issue, namely that Czech and Serbian are taught in this school, as well as German, which will be taught starting with the schoolyear 2022-2023, approval granted. Obviously the tendency to answer negatively is high in the other school, as over 60% (40,8% strongly disagree, 21,3% disagree) of the students know that these languages are not taught there, with an additional 12% of neutral responses.

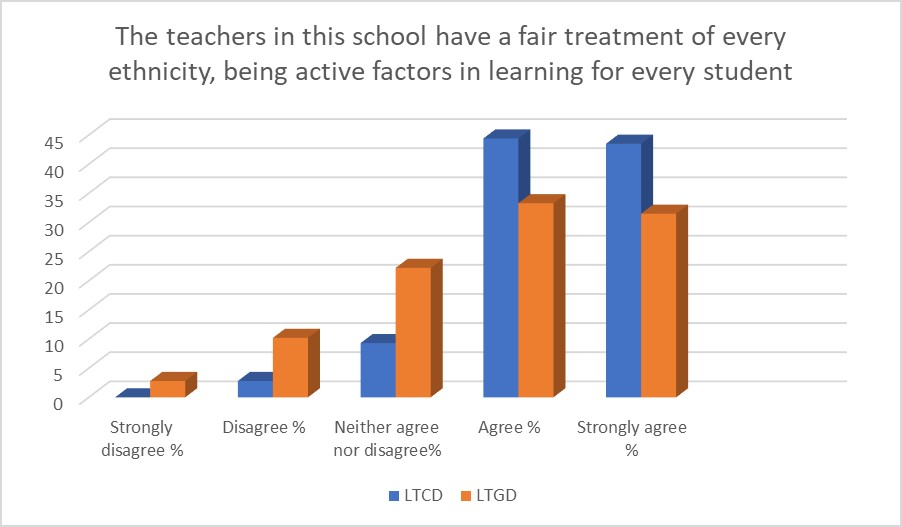

The third item, the fairness treatment given by teachers to students of every ethnicity, in which teachers become active factors in learning for every student, is targeted at identifying the teacher-students rapport. The differences here serve only as an indicator of students being accustomed to teachers who teach ethnic minorities, 90,7% - positive responses, as compared to 64,8% positive responses in the monocultural school.

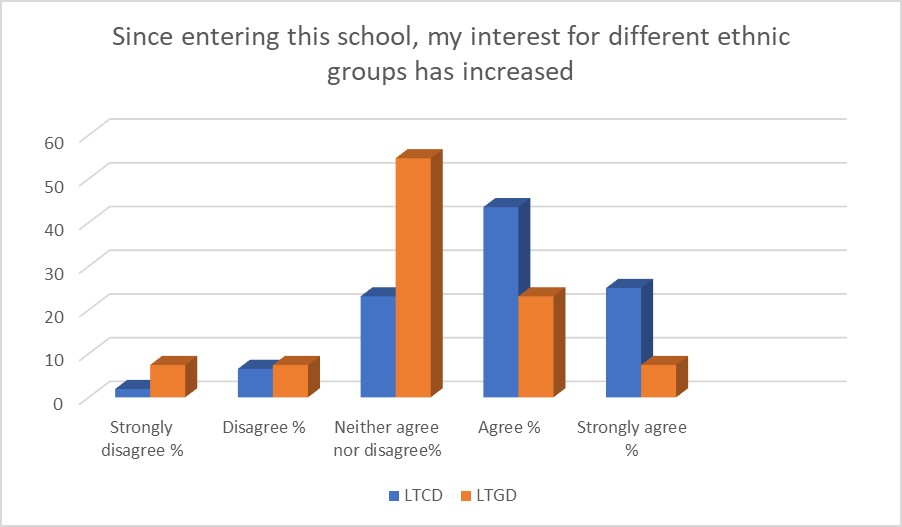

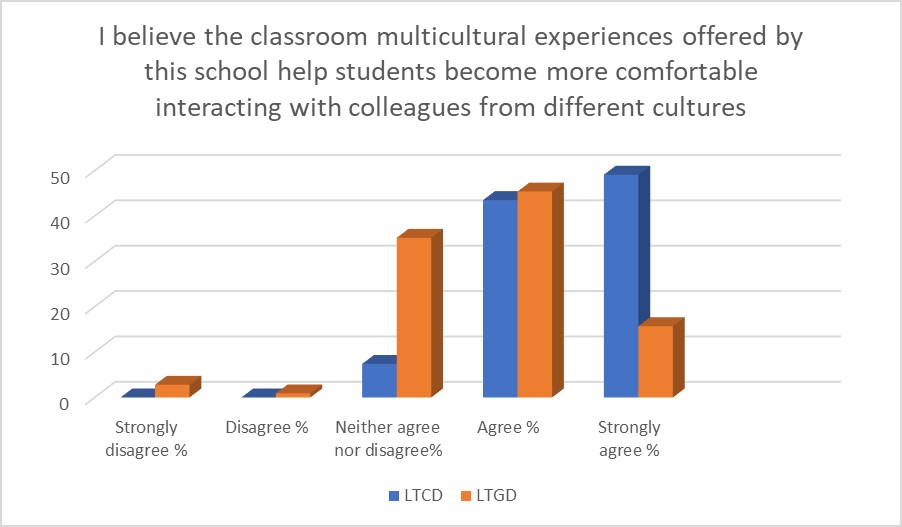

The fourth question is aimed at measuring the impact of the multicultural high school landscape on students. Obviously, the perception has improved in the multicultural environment: 68,5% strong and mild improvement, while no major changes have taken place in the other school, as seen in figure 4.

The percentage of students who are aware of their own cultural identity is high in the multicultural school (76,8%), as shown in figure 5. In contrast, only 50% of the students in the monocultural school are aware of this.

Item six builds on question five and places emphasis not on personal introspection regarding one’s self, but on that particular introspection as identifier of response to beliefs, attitudes, and behaviour belonging to cultures other than your own. In the first school 81,5% of the respondents clearly understand this type of response to cultural diversity, whereas in LTGD the percentage is a lot lower.

Regarding the informal school student-student rapport, questions seven to nine emphasise how students practically apply the statements about themselves from the previous answers in social contexts. And in both schools students are coherent and consistent with their beliefs. Question eight is primarily meant to measure formal school student-student rapport, in terms of team or groupwork for curricular purposes and here are the results:

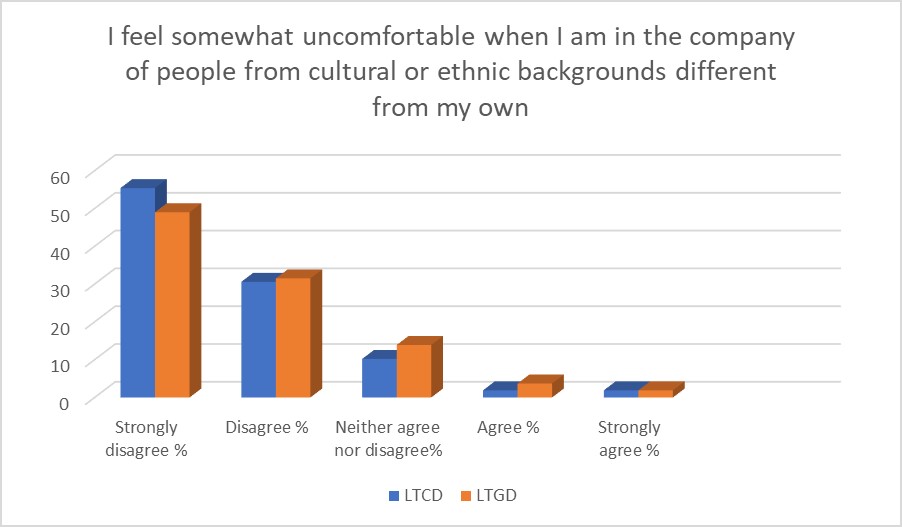

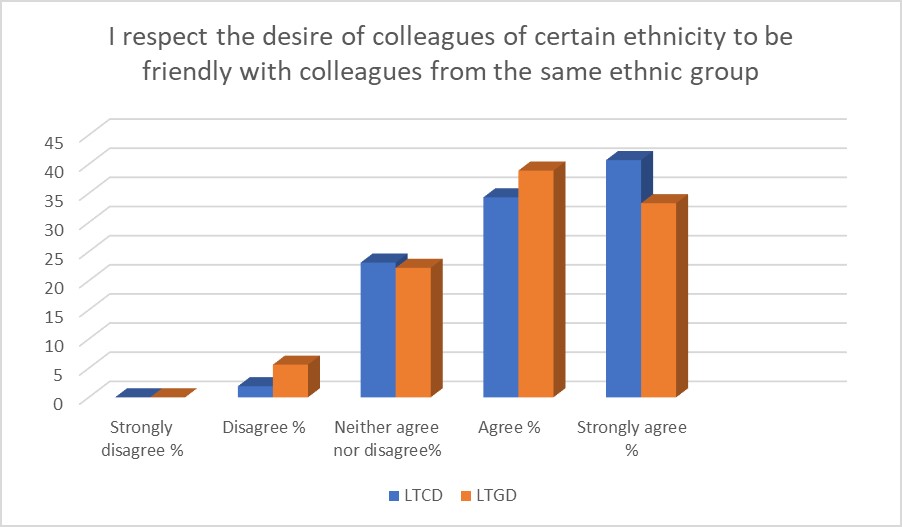

The following two items are about understanding stereotypical behaviour and the need for occassionally using the mother tongue and feeling comfortable with those who share your values.

The next item should be viewed as a step forward from the two aforementioned questions, and deals with challenging any forms of discrimination and building a culturally competent educational landscape. The LTCD students have been involved in such experiences and the positive response in the percentage of 92,6, as opposed to LTGD, where only 61,1% of the respondents provided positive information, is a validation of the institutional values students are educated in.

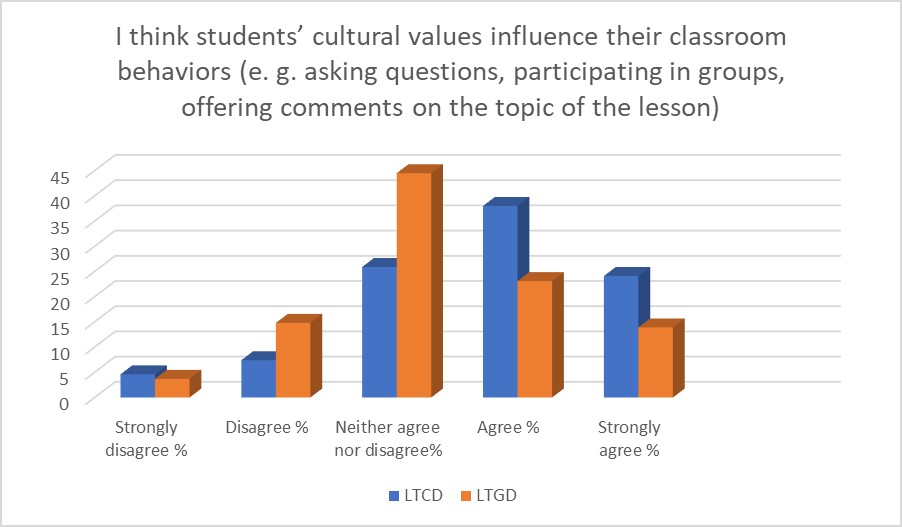

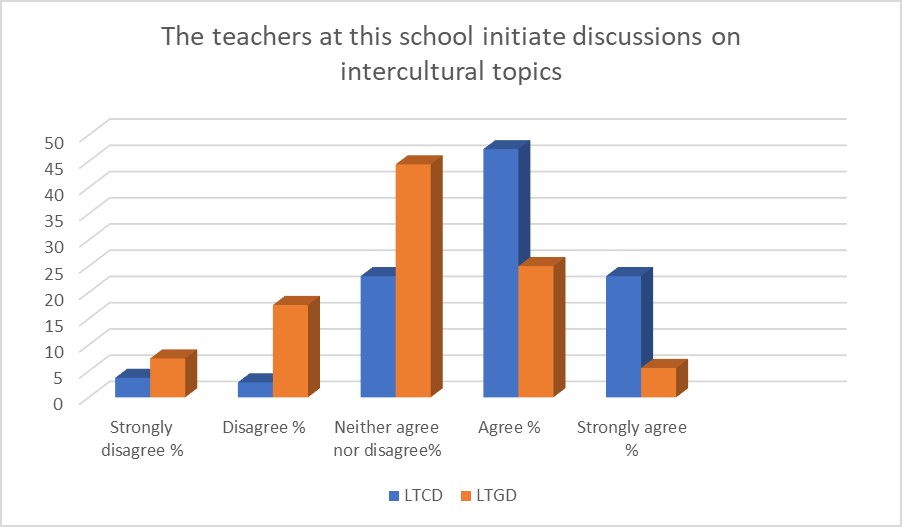

In the following question the idea of culturally competent teachers, who implement intercultural values and incorporate them in the teaching process is what triggers such survey outcomes. Indeed, the results in the multicultural school are self-explanatory and a clear indicator of openness that resides in contact with multiethnic classrooms.

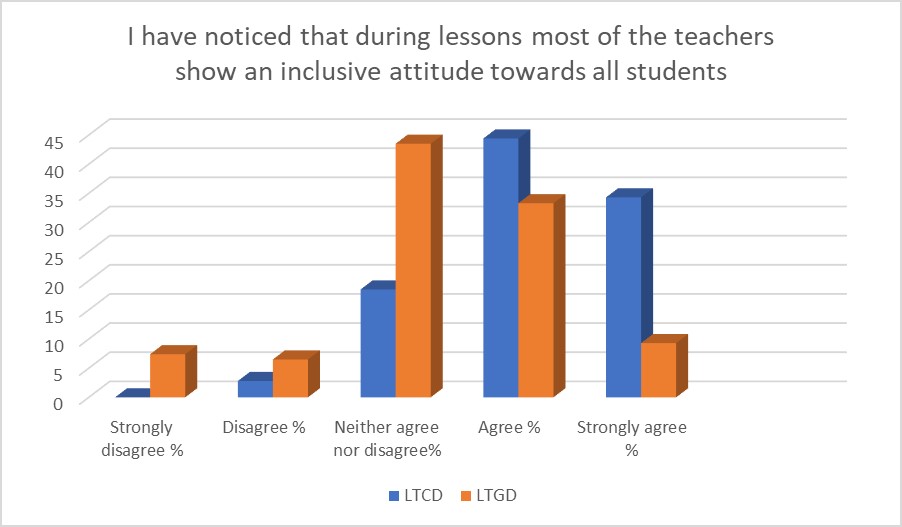

The forelast question addresses the issue of teachers showing understanding and paying attention to all students. Inclusion is essential in ensuring that all students benefit from fair treatment and are all valued. Thus, the results indicate tolerant and democratic learning environments with a 78,7 % of agreement in LTCD. By and large, nearly half of the LTGD students remain neutral (43,5%) in assessing the statement.

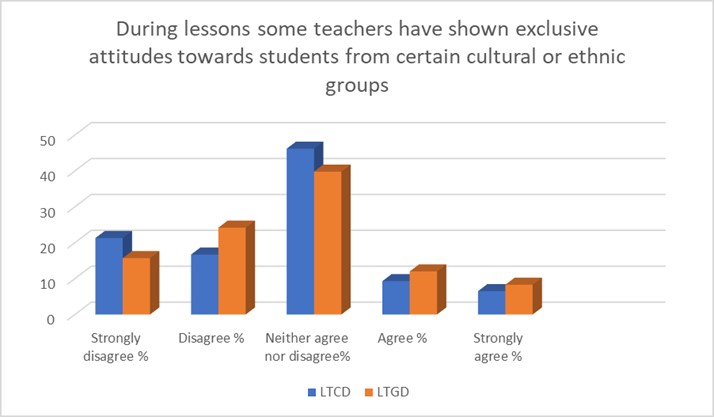

The last item, ethnic exclusionism, the harshest attitude, in which students encounter, in their schools, explicitly ethnically or culturally biased teachers, in terms of remarks, attitudes, syllabus information, or simple gestures. Be there remarks from teachers of the predominant culture or a minority one, inside and outside classrooms, exclusive attitudes and insensitive behaviour are serious issues and the equal results demonstrate that students are aware of possible culture clashes: a 38% of disagreement, strong and mild in the multicultural school, and a 39,9% in the slightly monocultural school. The percentage is not as similiar, though, in the ”neither agree nor disagree” range of responses: 46,2% the first school, 39,8% the second school, respectively in the second school, as well as in the agreement range 15,8%-20,3%.

Conclusion

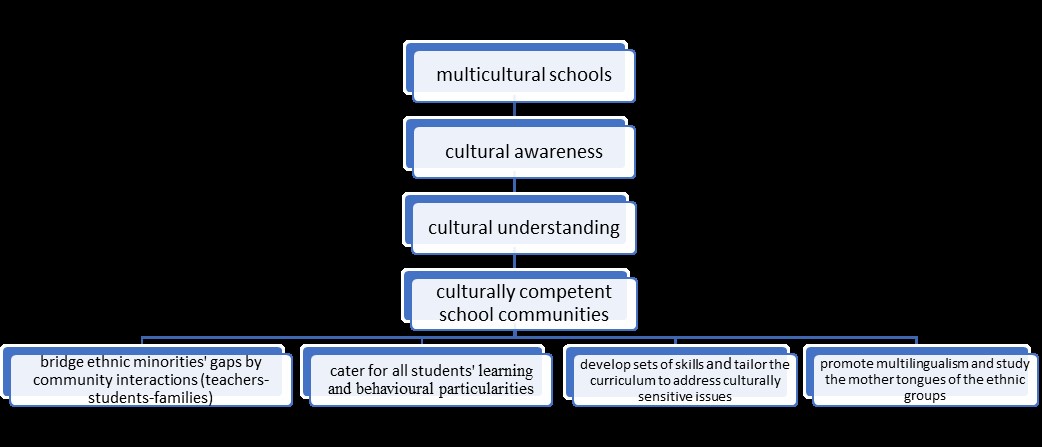

The survey meant to verify whether there is a positive relationship between a multicultural learning landscape and scholar success and whether educating culturally competent students would lead to accomplished and civically active adults. Although it is generally true that ethnic disparities and a tendency for exclusion are indicators of risk of abandonment, the survey has brought to surface certain features of a multicultural learning environment, which, if managed wisely, would trigger awareness, understanding and a set of abilities to adequately cater for all students, of various ethnicity, and ultimately lead to culturally competent schools. Undoubtedly, as seen from students’ responses, a major role in this endeavour is played by the teachers and school managers, who would have to apply these skills and tools in all areas, from incorporating cultural content in the curriculum, to adequately addressing sensitive issues in terms of school conduct, as well as bridging ethnic community gaps. The differences in percentage support this statement and turn the necessity for “cultural competency skills training” (Salmona et al., 2015, p. 35) into an imperative one. Another essential role belongs to the local communities and students’ families, for whom teachers of the culturally competent type serve as facilitators.

As regards the limits identified in the multicultural school, the students from Tourism classes are more frequently involved in school activities and community projects that promote interculturality in the Danube Gorge, as opposed to the respondents from the theoretical field of study (Mathematics-Informatics, Philology, Science) in both schools.

A further disadvantage is represented by the uncontrolled distribution of minority students in classes as a result of students' previous options for certain domains of study in comprehensive schools. The present diagnose can be turned by schools into a tool for developing intercultural programmes and projects that would benefit the educational environment and would encourage multicultural learning.

To sum up, a graphic representation by operationalisation of the main concepts of the survey can be seen in the following mind map, Figure 16:

In practice, should such a grid be applied in any multicultural educational institution, growth will be nurtured, students' results will be improved, inclusive school projects will have better outcomes, tolerance will replace discrimination and scholar success, in all its conceptual forms, could be ensured.

References

Bulzan, c. (2007). Problema Identităţii în Spaţiul Frontierei. Reflecţii Asupra Interdependenţelor Culturale Româno-Sârbe în Clisura Dunării [The Problem of Identity in the Border Space. Reflections on Romanian-Serbian Cultural Interdependencies in the Danube Gorge]. Sociologie românească, 5(02), 130-148.

Constantin, E. C., & Badea, G. L. (2014). Interculturality in Banat. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 3548-3552.

Coșarbă, E., Roman, A. F., & Costin, A. (2021). Parents' perception regarding the concerns, competencies and perspectives of involvement in non-formal activities. Technium Social Sciences Journal, 26, 177-185.

Costin, A., & Roman, A. F. (2020). Discussing with the Parents of High School Students: what do They Know about Drugs?. Postmodern Openings, 11(1), 01-19.

DeAngelis, T. (2015). In search of cultural competence. Monitor on Psychology, American Psychological Association, 46(3), 64.

Dweck, C. S. (2017). Working with Roma: Participation and empowerment of local communities. European Union for Fundamental Rights. Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/

Garbarino, J. (2008). The meaning and implications of school success. The Educational Forum, 40(2), 157-167.

Goleman, D. (2018). Inteligența Emoțională [Emotional intelligence]. Curtea Veche Publishing.

Hattie, J. (2014). Învățarea Visibilă. Ghid pentru profesori [Visible Learning for Teachers. Maximizing impact on learning]. Editura Trei.

Kalet, A. L., Fletcher, K. E., Ferdman, D. J., & Bickell, N. A. (2006). Defining, navigating, and negotiating success: The experiences of mid-career robert wood johnson clinical scholar women. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(9), 920-925.

Narai, E. (2012). Maghiarii şi cehii din judeţele Caraş şi Severin în perioada 1944-1948 [Hungarians and Czechs in Caras and Severin County in the period of time 1944-1948]. în Banatica, Reşiţa, 22, 2012, 381-396.

Rew, L., Becker, H., Cookston, J., Khosropour, S., & Martinez, S. (2003). Measuring Cultural Awareness in Nursing Students. Journal of Nursing Education, 42(6), 249-257.

Salmona, M., Partlo, M., Kaczynski, D., & Leonard, S. (2015). Developing Culturally Competent Teachers: An International Student Teaching Field Experience. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(40).

Van Roekel, N. P. D. (2008). Promoting educators’ cultural competence to better serve culturally diverse students. National Education Agency.

Westheimer, J., & Kahne, J. (2004). What Kind of Citizen? The Politics of Educating for Democracy. American Educational Research Journal, 41(2), 237-269.

York, T., Gibson, C., & Rankin, S. (2015). Defining and Measuring Academic Success. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 20.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 May 2023

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-962-7

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

6

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-710

Subjects

Education, reflection, development

Cite this article as:

David-Izvernar, M., & Roman, A. F. (2023). The Multicultural Educational Environment and School Success: From Awareness to Cultural Competence. In I. Albulescu, & C. Stan (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development - ERD 2022, vol 6. European Proceedings of Educational Sciences (pp. 158-170). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.23056.15