Abstract

The present paper aims to consider the communicative effect produced by the English tag question in professional communication. Tag questions are viewed as hedging strategies, strategies of politeness and strategies of persuasion. The author seeks to understand whether tag questions perform similar communicative tasks in the two types of professional discourse: courtroom discourse and business communication and compares their relevant frequencies. For the purpose of the analysis a corpus of 2500 instances of tag questions have been collected and subjected to contextual, qualitative, quantitative and comparative statistical analyses. Qualitative contextual analysis was conducted to determine the communicative tasks (hedging, persuasion and politeness) performed by tag questions. Comparative analysis was conducted to identify the differences observed in the use of tag questions in the two types of discourse: courtroom discourse and business communication. In the course of the analysis it was concluded that the number of coercive tag questions used for the purpose of persuasion prevailed, the only structural type of tag questions used as persuasive strategies was canonical. Tag questions in the business-communication corpus were used as positive-politeness strategies. No instances of tag questions used for politeness purposes were found in courtroom discourse. No hedging potential was discovered for the English tag question in professional communication.

Keywords: Communicative strategy, hedging, professional communication, persuasion, politeness, tag question

Introduction

In the course of communication, the speaker seeks to make their messages effective to produce the desired impact on the listener’s cognition. At the same time, the speaker feels the need to make their utterances pragmatically correct and maintain rapport (Spencer-Oatey, 2008). The most general logical laws that govern speech behaviour were formulated by Grice (Strawson & Wiggins, 2001), however, attempts to apply the Cooperative principle to analyses of various discourse types have demonstrated its limitations by what has been designated in linguistics as the categories of politeness (Brown & Levinson, 2014; Hammood, 2016; Kádár & Haugh, 2013; Lebedeva & Kuzhevskaya, 2019; Malyuga & Orlova, 2018, Spencer-Oatey, 2008, Savić, 2014), hedging (Caffi, 2007; Fraser, 2010; Lebedeva & Gribanova, 2019; Rezaei et al., 2017) and persuasive communication (Dzialoshinskiĭ, 2012; Lebedeva & Romanova, 2018a; Lebedeva & Romanova, 2018b; Mulholland, 2005; Perloff, 2003; Sorlin, 2016), since the principle itself characterizes a socially neutral communication scheme.

Problem Statement

Despite an abundance of previous research on tag questions (Baker, 2015; Kimps, 2018; Lebedeva, 2019; Malyuga & Orlova, 2015, Rimmer, 2019), their conversational properties remain understudied. Previous research into the field has provided a description of the structural and functional diversity of tag questions, their pragmatic potential, prosodic properties as well as some sociolinguistic factors that condition their usage in discourse. In the course of this research, there came understanding of the need to look for new approaches to the study of tag questions, since their functional description does not reflect their discursive diversity. For a long time, tag questions have been regarded as a feature of spoken English, descriptions of their performance in institutional discourse have been scarce.

Research Questions

The present paper addresses the following research questions:

How do tag questions impact communication?

What communicative tasks can be performed by tag questions in institutional discourse?

Do tag questions perform similar communicative tasks in courtroom discourse and business communication?

Is there any correlation between the structural type of the tag question and the communicative task it performs in the situation?

Purpose of the Study

The present paper aims to consider the communicative potential of the English tag question in two types of institutional discourse: courtroom discourse and business communication. Tag questions are viewed as hedging strategies, strategies of politeness and strategies of persuasion. The author seeks to understand whether tag questions perform similar communicative tasks in the two discourse types and aims to compare their relevant frequencies.

Research Methods

For the purpose of the analysis a corpus of 2500 instances of tag questions have been collected and subjected to contextual, qualitative, quantitative and comparative statistical analyses. Qualitative contextual analysis was conducted to determine the communicative tasks (hedging, persuasion and politeness) performed by the tag questions in the situations they were obtained from. Quantitative analysis allowed to compare the relevant frequencies of tag questions used to perform the three indicated communicative tasks. Comparative analysis was conducted to identify the differences observed in the use of tag questions in the two types of institutional discourse: business communication and courtroom discourse. Samples of courtroom discourse situations for the analysis of tag questions have been obtained from transcripts of D. Westerfield, J. R (https://www.unposted.com/david-westerfield-trial-transcript) . MacDonald (https://ru.scribd.com/doc/261155375/Grazzini-Rucki-v-Rucki-Trial-Transcript) and O. J. Simpson (https://famous-trials.com/simpson/1864-excerpts) trial procedures, as well as from several films which provide descriptions of courtroom sittings: ‘The Lincoln Lawyer’ (2011), ‘Suits’ (2011) and ‘The Judge’ (2014). Sample situations for the analysis of tag questions in business communication have been obtained from http://businessenglishpodcast.com/ and https://www.voices.com/, as well as some business text-books (Hughes & Naunton, 2008).

Findings

Regarding their functions two classes of tag questions are generally distinguished: informational and affective (Tottie & Hoffmann, 2006). To the informational type linguists generally refer tag questions that aim to elicit information: these questions generally bear the rising tone on the tag and are the result of the speaker’s desire to clarify areas of lacking knowledge. The other class is confirmatory tag questions which are pronounced with the falling tone on the tag and prompt the listener to confirm what the speaker has just said. Under the class of affective tag questions in most existing classifications fall facilitating tag questions which prompt the addressee to participate in interaction and should be regarded as a conversational strategy, attitudinal tag questions which emphasize what the speaker is saying, peremptory which follow statements of generally acknowledged facts and aggressive or challenging tag questions which function as confrontational strategies. Of these at least two types – confirmatory and peremptory tag questions – can be regarded as strategies of persuasion.

Tag questions as strategies of persuasion

In the past decades the volume of persuasive communication has grown considerably, it is found in advertising, marketing and on the Internet. It is key to political success. It has penetrated the framework of society and become highly institutionalized. Persuasive communication is more complex than ever before. Nowadays it is becoming more subtle and devious.

Persuasion can be defined as a process of convincing the addressee to change their attitudes or behaviour concerning an issue in an atmosphere of free choice. Persuasion does not aim to change people's minds; the listener decides themselves whether to alter their attitudes or to resist persuasion. Sorlin (2016) notes that the use of persuasive strategies in the process of persuasion does not guarantee mandatory success, since pervasiveness is just an attempt to influence the recipient. Persuasiveness always involves the study of the recipient’s opinion (Perloff, 2003), i. e. analysis of their feelings concerning the issue discussed and what goals they have in mind. If the speaker understands the interlocutor’s attitude to the problem, it becomes possible to imagine how to change it and in accordance with this develop a certain pattern of persuasion. Understanding what benefits the recipient will derive from the chosen strategy and what impact this this strategy can have on the recipient plays a significant role in the process of persuasion. In order to attain persuasive goals, it is necessary to: 1) understand the interlocutor's attitude to the issue discussed; 2) understand the possible causes of this attitude; 3) assess what relevance the issue discussed has for the interlocutor and 4) what their ultimate goals are. After solving the above-mentioned tasks, it becomes possible to successfully persuasuade the interlocutor that they are the only beneficiary of the proposed position, why it is relevant for him, how this position meets their expectations and how it could satisfy their needs.

It is generally assumed that the purpose of tag questions which bear the falling tone on the tag is to get the recipient to agree with the proposed statement, since the proposition suggested in the body of the tag question is subconsciously perceived by the interlocutor as a ready-made answer to the question, the answer that is expected from them. It is difficult to disagree with a statement given in the form of a tag question, because the effect of the suggested statement is enhanced by the falling tone on the tag which presupposes approval. Then, what is the persuasive potential of the English tag question? What makes it a powerful tool in the hands of sales consultants, managers, business coaches and politicians? It is a unique grammatical structure where the proposition is confirmed twice: in the body which states the proposition and bears affirmative intonation (the falling tone) and simultaneously in the tag, which enhances the impact.

Owing to this the persuasive type of tag questions is particularly common in marketing. The following conversation between car sellers and a buyer illustrates well the communicative impact produced by confirmatory tag questions used as persuasive strategies:

Sales 1: You’d enjoy driving a nice new car, ↓wouldn’t you?

Customer: I probably would enjoy it, that’s right.

Sales 2: Imagine your old car is costing you a lot in repairs, ↓isn’t it?

Customer: It certainly is.

Sales 1: and I expect you’re going on holiday soon, ↓aren’t you?

Customer: Y, …um, that’s correct

Sales 2: So, this might be a good time to think about buying a new car, ↑right?

Customer: Well, possibly…

Sales 1: Because you wouldn’t want to break down in the middle of your holiday, ↓would you?

Sales 2: You didn’t say “no” then, ↓did you?

Customer: No, I said of course… (Allison et al., 2008, audio track 2:05)

The sellers seek to persuade the customer that their paramount task is to meet the customer’s needs, that they provide valuable services and a profitable offer, that the customer is the only beneficiary of the upcoming transaction where they are intermediaries. However, it should be noted that such usage of the tag question teeters between persuasion and manipulation and does not respond fully to the definition of persuasiveness.

Persuasive types of tag questions are equally common in courtroom discourse, they are normally found in the speech of defence attorneys and lawyers during cross-examination. In the example retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XkxjunGJfjc (Killer Cross Examination) the defence attorney arranges the cross-examination in the form of a series of confirmatory tag questions, with the body containing assumptions made by the lawyer and the tag checking confirmation from the witness.

“Mr. Spencer, you have been around people who have used narcotics, ↓haven’t you?”

“And you’ve seen people who in your experience appeared to be high, ↓haven’t you?”

The lawyer draws the jury’s attention to the fact that the testimony given under oath in the course of the court session contradicts the testimony given by the witness before.

“You just told the jury a second ago that it didn’t dawn on you to think about that. Now you’re saying that you actually may have said something about that. Those are two different things, ↓aren’t they?”

“Today you’ve told the jury something different, ↓haven’t you?”

Throughout the interrogation the witness asks the lawyer to rephrase deviously formulated tag questions. The judge makes a similar remark about the use of tag questions and suggests that the lawyer ask a general question.

Attorney: I’m literally trying to put to him the questions.

Judge: Then ask your question.

Attorney: Okay. Detective Doty said to you…

Judge: Did detective Doty….

Attorney: This is cross. So, I can ask a leading question, ↑can I?

The lawyer insists on the chosen form of questioning, as it allows him to achieve the desired effect. In his last utterance the attorney resorts to the use of the positive-polarity tag question with the rising tone (Positive-polarity tag questions always bear the rising tone on the tag (Author’s note).) on the tag to signal his conviction, as he is sure of his right to ask leading questions.

Several scenes featuring courtroom sittings are found in the film “The Devil’s advocate” (1997).

During the hearing of a harassment case the parties interrogate a thirteen-year-old pupil, Barbara. In the course of the examination-in-chief the prosecutor asks her predominantly special and general questions which aim to reveal the details of the case.

The defendant's lawyer, Mr. Lomax seeks to destroy the victim's credibility – that is, to convince the judge and jury that the girl’s biased attitude to the teacher and learning problems have provoked the harassment accusations.

The lawyer, Mr. Lomax, interrogates the harassment victim using confirmatory tag questions with the falling tone on the tag which signal a strong degree of conviction, thus building his own version of the events, for example:

<... > You're writing here about Mr. Gettys, ↓aren't you?

<... > this was the first time you told the story about Mr. Gettys, ↓wasn’t it?

You threatened those children, ↓didn't you?

<... > That's what really happened, ↓isn't it?

This harsh cross-examination has the desired effect on the jury and laymen present in the courtroom: the lawyer discredits the witness and wins the case.

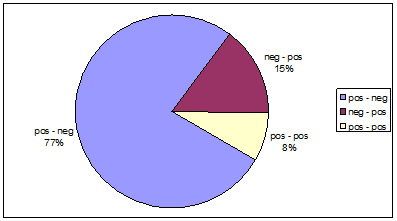

Note should be made about the structural types of tag questions used as persuasive strategies. Only canonically structured tag questions perform persuasive tasks (Figure 1).

Tag questions as strategies of politeness

There are two major types of goals that the speaker pursues in the process of communication. For one thing, they seek to put the message through to the interlocutor in the most effective way possible, for another thing, they calculate the "price" of different approaches to transmitting the message, which are more or less appropriate to the setting. The latter aspect deserves special attention, since very often the achievement of a communicative goal turns out to be destructive to rapport and may result in "loss of face" (Brown & Levinson, 2014) leading to sour relationship, social disapproval, emotional discomfort, etc. (Issers, 2003).

In business-communication there are situations where establishing contact with the interlocutor and subsequent successful interaction with them are prime. For this reason, much attention is given by the interlocutors to building and maintaining rapport, for example:

We haven’t been very successful in our branding efforts, ↑have we? (Yeu, 2018)

In this situation George speaks as if Susan’s knowledge were equal to his or as if Susan were him. Brown and Levinson’s (2014), the proponents of the Theory of Politeness define this strategy as personal-centre switch. Using the tag have we? George seeks Susan’s support and understanding. He wants to convince Susan that they belong to the same team and appeals to mutual effort.

Although previous research (Lebedeva & Kuzhevskaya, 2019) showed that the use of negative-politeness strategies prevailed in business communication, concerning tag questions the results were opposite: all the tag questions in the business-communication corpus were used as positive-politeness strategies.

No instances of tag questions used as strategies of politeness were found in the course of the analysis of samples of courtroom discourse.

Conclusion

In the course of the conducted analysis the author sought to consider the communicative potential of the English tag question, to identify peculiarities of the use of tag questions as persuasive, hedging and politeness strategies in the two institutional discourse types: business communication and courtroom discourse. The analysis yielded the following results:

1) The number of tag questions used for the purpose of persuasion prevailed in both types of institutional discourse: business communication and courtroom discourse;

2) The only structural type of tag questions used as persuasive strategies was canonical;

3) In business-communication where building and maintaining relationship with the interlocutor for the purpose of subsequent successful interaction were of paramount importance tag questions were frequently used as strategies of politeness. Despite the prevailing character of negative-politeness in business communication, concerning tag questions the results were opposite: all the tag questions in the business-communication corpus were used as positive-politeness strategies.

4) No instances of tag questions used as strategies of politeness were found in the course of the analysis of samples of courtroom discourse.

5) No hedging potential was discovered in the use of the English tag question, since no instances of tag questions used as hedging strategies were found in the course of the analysis.

The conducted analysis has proved the feasibility of the approach to the treatment of the English tag question proposed by the author and has laid the foundation for further research into the use of tag questions as communicative strategies.

References

Allison, J., Townend, J., & Emmerson, P. (2008). The Business Upper-Intermediate Student’s Book. Macmillan.

Baker, D. (2015). Changing English: Tag questions. ELT Journal, 69(3), 314-318. DOI:

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. (2014). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Studies in interactional sociolinguistics (4). Cambridge University Press.

Caffi, C. (2007). Mitigation. Studies in Pragmatics 4. Elsevier.

Dzialoshinskiĭ, I. M. (2012). Kommunikativnoe vozdeistvie: misheni, strategii, tekhnologii [Communicative Impact: Targets, Strategies and Technologies]. NIU VShE.

Fraser, B. (2010). Pragmatic Competence: The Case of Hedging. In G. Kaltenboeck et al. (Eds.), New Approaches to Hedging (pp. 15-34). Emerald Publishing. DOI:

Hammood, A. (2016). Approaches in Linguistic Politeness: A Critical Evaluation. International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Culture (Linqua-LLC), 3(3), 1-20.

Hughes, J., & Naunton, J. (2008). Business Result. Upper-Intermediate Student’s Book. Oxford University Press.

Issers, O. S. (2003). Kommunikativnye strategii i taktiki russkoi rechi [Communicative Strategies and Tactics of the Russian Language]. Editorial URSS.

Kádár, D., & Haugh, M. (2013). Understanding Politeness. Cambridge University Press. DOI:

Kimps, D. (2018). Tag questions in conversation: A typology of their interactional and stance meanings. John Benjamins.

Lebedeva, I. S. (2019). Razdelitel'nyi vopros, ili universal'nyi kommunikativnyi khod? [Tag Question, a Universal communicative strategy]. In Sorokina T. S. (Ed.), Funktsional'no-kognitivnye aspekty aktualizatsii grammaticheskikh form i struktur v sinkhronii i diakhronii (na materiale angliiskogo iazyka) [Functional and Cognitive aspects of the Use of Grammatical Forms and structures: synchronous and diachronic approaches] (pp. 267-352). Moscow.

Lebedeva, I. S., & Gribanova, T. I. (2019). Hedging in Courtroom Discourse. Issues of Applied Linguistics, 2(34), 70-92.

Lebedeva, I. S., & Kuzhevskaya, E. B. (2019). Strategies of Politeness in Business Communication. Bulletin of the Moscow State Linguistic University. Humanities, 12(828), 62-73.

Lebedeva, I. S., & Romanova, I. D. (2018a). Modal'nye glagoly kak sredstva vozdeistviia v personal'nom i institutsional'nom diskurse [Communicative Impact of Modal Verbs in Personal and Institutional Discourse]. Bulletin of the Moscow State Linguistic University. Humanities, 15(810), 77-86.

Lebedeva, I. S., & Romanova, I. D. (2018b). Persuazivnost', manipuliatsiia i lingvisticheskoe prinuzhdenie v biznes-kommunikatsii [Persuasion, Manipulation and Linguistic Coercion in Business Communication]. Issues of Applied Linguistics, 1(29), 30-45.

Malyuga, E. N., & Orlova, S. N. (2015). Lingvopragmaticheskii analiz voprosno-otvetnogo kommunikativnogo bloka v delovom interv'iu [Linguistic and pragmatic analysis of the question-answer communicative block in a business interview]. Izvestiia Iuzhnogo federal'nogo universiteta. Filologicheskie nauki, 3, 44-50.

Malyuga, E. N., & Orlova, S. N. (2018). Linguistic pragmatics of intercultural professional and business communication. Springer.

Mulholland, J. (2005). Handbook of persuasive tactics A practical language guide. Taylor & Francis e-Library.

Perloff, R. (2003). The dynamics of persuasion: Communication and attitudes in the 21st century (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Rezaei, K., Hafeshjani, E. & Zaboli, A. (2017). Contrastive Analysis of Hedges in English and Persian Linguistics Articles. In Proceedings of the National Conference on Modern Knowledge and Technology in engineering in the Technology Era (pp. 1661-1677). Tehran, Iran.

Rimmer, W. (2019). Questioning practice in the EFL classroom. Training, Language and Culture, 3(1), 53-72. DOI:

Savić, M. (2014). Politeness through the Prism of Requests, Apologies and Refusals: A Case of Advanced Serbian EFL Learners. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Sorlin, S. (2016). Language and Manipulation in House of Cards: A Pragma-Stylistic Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan. DOI:

Spencer-Oatey, H. (2008). Face, (Im)politeness and Rapport. In H. Spencer-Oatey (Ed.), Culturally speaking: Culture, Communication and Politeness Theory (pp. 11-47). Continuum.

Strawson, P., & Wiggins, D. (2001). Herbert Paul Grice (1913-1988). Proceedings of the British Academy, 111, 515-528.

Tottie, G., & Hoffmann, S. (2006). Tag questions in British and American English. Journal of English Linguistics, 34(4), 283-311. DOI:

Yeu, Anh Van. (2018). ESP & Business English. ESP & Business English. Improving Brand Image. http://www.yeuanhvan.com/esp-business-english/business-dialogues/7363improving-brand-image

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

12 October 2022

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-957-3

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

4

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-399

Subjects

Teaching methods, language for specific purposes, business English, translation studies, applied linguistics, intercultural business communication

Cite this article as:

Lebedeva, I. S. (2022). The Coercive Effect of Tag Questions in Professional Communication. In V. I. Karasik, & E. V. Ponomarenko (Eds.), Topical Issues of Linguistics and Teaching Methods in Business and Professional Communication - TILTM 2022, vol 4. European Proceedings of Educational Sciences (pp. 164-171). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.22104.19