Abstract

Defining relevant learning outcomes is a topical issue at all levels of education. The approach is encouraged by the recent educational policies promoted at the international and national levels and are facilitated by the societal and labor market chances and tendencies. The principle of learning outcomes-based study programs design and implementation is adopted for purposed related to the need for increasing educational programs relevance, transparency and accountability. However, recently there is a recurrent concern about the real impact on the principle of learning outcomes based higher education curriculum would have in promoting a positive change in the academic practice. Considering this struggle, in the present paper we will look at the problems and solutions identified and reported in the recent research and attempt to set the bases for a possible mind model that would help us faculty members reflect upon and implement learning outcomes in academic study planning and teaching.

Keywords: Higher education, learning, learning outcomes, relevant learning

Introduction

The present paper addresses the topical issue of learning outcomes understanding, writing and use in supporting the effective professional development in higher education. Learning outcomes is a key word in the present European higher education reforms’ agenda. However, different European countries are in different stages in the adoption of the learning outcomes term and principle. We will attempt to offer a general overview on the meanings and use of learning outcomes in higher education and articulate an image on how the construct is understood and put to use, in order to select a set of anchors for a systemic approach of the learning outcomes principle.

Problem Statement

In a general perspective, the term means” statements regarding what a learner knows, understands and is able to do on completion of a learning process” (EC 2017/C 189/03). In a more analytic understanding, learning outcomes are defined in terms of knowledge, skills and responsibility and autonomy the graduate of a certain course or level of training is able to demonstrate at the completion of his studies. The term is often connected with the development of professional competences and with mastery learning.

While most of the definitions are consonant in terms of the types of acquisitions enumerated, periodically new meanings are added to the term. It is the case of a recent definition adopted by the European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (CEDEFOP, 2017):” sets of knowledge, skills and/or competences acquired by the person or which the person can demonstrate at the end of a learning process that can be either formal, non-formal or in-formal. Such an understanding opens up the use of learning outcomes in a flexible, personal way, for the recognition of formal and non-forma learning experiences and results. In fact, this is a recent tendency that we see undertaken at the level of European Commission, through initiatives such as the The Europass platform, Individual learning accounts initiative or the Upskilling pathways initiatives (European Commission, 2021).

The focus on learning outcomes is frequently labeled as a paradigm shift (Halasz, 2017), and as a guiding principle of action. The adoption of the principle is associated with relevant curriculum and Europeanisation of educational programs. Learning outcomes - a as well as in the Europeanization (Halasz, 2017; Sweetman, 2019a).

In concrete terms, the learning outcomes-based education is presented as a solution for reducing the discrepancy between the universities study offers and the expectancies of the employers (European Council, 2017). It is also regarded as a vector for insuring the inner coherence of the educational programs (Lennon, 2018) and continuing curriculum development (Tam, 2014), as a benchmark for quality assurance (Hansen et al., 2013; Randahn & Niedermeier, 2017), as a mobile for professional access and progression (Lennon, 2018). In the international higher education area, the definition and use of compatible learning outcomes for similar qualification is regarded as a solution for internationalization of studies, for the international recognition and transfer of study credits, for increasing employees’ mobility on the labor market and for improvement of employability rate (Lennon, 2018).

Whatever it is understood or approached for, the issue remains topical at the international and national levels, as one of the most recent studies undertaken at the level of European countries and measuring the level of skills a development, activation and matching in different national settings (European skills index, 2020) offer concrete arguments in favor of focusing the professional development on appliable learning outcomes. This, in the above-mentioned study, Romania has the lowest performance in skills development (rank 31st), poor performance in skills activation (rank 29th) and an average one in skills matching (rank 13th). It belongs to the “low-achieving” group of countries. These data very clearly prove the need for reorganization of study programs in terms of skills development and also the need for a better tune between the Romanian educational and work market.

Research Questions

Our interest in the present paper is to set the lines for a framework that could help guide the reorganization of teacher training programs in the light of the learning outcomes principle. The research questions we attempted to answer at were:

What are the most common concerns and explanations regarding the use of learning outcomes as a fundament for relevant study programs development?

What are the factors that could help writing and using the learning outcomes approach for increasing the relevance of teacher training in higher education?

Purpose of the Study

Given the addressed research questions, we looked at how learning outcomes use is seen in the existing scientific literature in order to identify the general lines of the rhetoric related to the understanding and use of learning outcomes, to synthetize the critical concerns and solutions reported and to delineate possible anchors for an integrative model of implementing the learning outcomes principle of action in higher education.

Research Methods

We carried out a critically analysis of recent works and articles that argue on the meanings and use of learning outcomes in higher education: comparative and case study papers, learning ourcomes writing guides. The topics we looked at were: meanings associate to the learning outcomes concept, challenges in implementing the principle and solutions in the effort for the learning outcomes best use in the curriculum design and development. By integrating the findings, we articulated the main anchors for an integrative action model in the higher education implementation of the learning outcomes principle.

Findings

Countries of the European Community and generally the whole higher education world shift towards reforming the educational programs in the light on learning outcomes. There is an international policy context that support and push for this trend, doubled by strong recommendations and regulations of the European Commission such as the 2017 Recommendation on the European Qualifications Framework for lifelong learning. Recently, a new European Skills agenda was issued and it is presented as a 5 years plan to support individuals and businesses develop more and better skills and to put them to use. At national levels, based on the above-mentioned regulations, there are initiatives for learning outcomes writing and use in higher education. At the national level, Romania is in tune and approved with all these structures and recommendations and we are in the process of implementing them.

While learning outcomes driven study programs increasingly become a must for higher education (Curaj et al., 2018). there are recent research data that indicate a certain struggle in assimilation and use of the term as well as in the implementation of the learning outcomes-based study programs principle.

On one hand, there are voices who argue that curriculum design based on outcomes is already traditional in dcertain institutions, even though we may have used different terms, such as competences, aims or objectives. The shift towards learning outcomes has in fact a higher stake associated with its potential for in relation with:

the labour market expectancies (it emphasizes the connection between the professional competencies and the learning outcomes);

international regulation and tendencies (they emphasize the need for more appliable study acquisitions);

mutations and mobility existing on the labor market (these phenomena require flexible, transferable professional skills and a disposition for continuing professional development and lifelong learning);

national settings and reality regarding the relevance of the professional development in relation with the work area expectancies.

On the other hand, there are studies that bring into light the limited effect of learning outcomes policy application. Thus, for instance, on a bases of a comparative study, Lennon (2018) concludes that:

Policies on learning outcomes in higher education regulation are not having the intended impact. This is a significant finding considering the amount of time, effort and political will being put into learning outcomes policies as a result of the Bologna process within national governments, quality assurance agencies as well as the institutions. (p. 541)

Nevertheless, building on this conclusion, Lennon argues that the situation may be an effect of the way policies are formulated and applied.

The literature analysis leaded us to identify three types of rhetoric when it comes to learning outcomes approach. Firstly, there is a philosophical discourse, of a reflective manner, based on the idea that the implementation of the principle is influenced by understanding. This approach is associated with an effort to define the concept of learning outcomes and to argument in favor of the idea that apart from being a formal, official task, the formulation and use of learning outcomes must be a useful exercise for increasing the relevance of educational offers. Secondly a policy/ official discourse can be delineated. This type of discourse is based on the statement that the learning outcomes approach aims to respond to the new realities of the work market (frequent changes in job roles and geographical locations) and of social expectations. Consequently, the learning outcomes approach is seen as an instrument for quality assurance and curriculum development. The third type is a practical/action discourse, based on the importance of the way policies are understood and put to work. For the orientation of practice, a frequently cited contributor to the pedagogical grounding of learning outcomes is John Biggs (2003). He proposes a model of ‘constructive alignment’, which implies that both planning and implementation of teaching is understood as construction and mindful participation in learning activities. Learning outcomes made clear to students would help them better organize their learning.

The second research question imposed looking at the challenges and solutions implemented. In order to identify possible answers, we analyzed the recent literature that approach the implementation of learning outcomes-based education and training in a comparative manner. We looked at:

meanings attributed to the concept of learning outcomes

orientation of different higher education institutions in relation to learning outcomes

solutions for putting the learning outcomes to a good use.

Most of the analyzed situations reflected a preoccupation for learning outcomes imposed by either general professionalization policies or by national education policies. Yet, at the level of institutions there are certain accents that prevail. Thus, the learning outcomes tend to be either defined at the level of the whole study program, in a general, close-ended manner, or, contrarily, at the level of each course or training module, in a flexible, open-ended manner. First approach is rather product oriented, while the second is rather process oriented (Sweetman, 2019a). While the first approach is rather supporting accountability actions and quality evaluation, while the second could be a better approach for educational planning, reflection and cooperation and curriculum development.

Different meanings attributed to the concept of learning outcomes and their use are in most of the institutions that implement the principle related with:

the conceptions on learning (Prøitz et al., 2017). Thus, the critical literature argues that learning outcomes: are a managerial decision that can inhibit useful learning processes, that there is the risk that at their adoption we will fail to recognize explorative and unintended learning or that there are goals of higher education which” cannot be expressed as learning outcomes” because they either become active late after graduation or because they cannot be assessed easily. (Erikson & Erikson, 2019, p. 2299)

the conceptions on academic knowledge (Muller &Young, 2014). Some of the investigated cases highlight the institutional analyses on the purpose and types of knowledge the university is asked to vehiculate. In relation to this, the status of factual knowledge against (professional) skills is critically discussed as having implications for the type of learning outcomes the institution targets.

the conceptions on the status of a professional programs of study. Here the contributions of Prøitz et al. (2017) are particularly relevant as they highlight the fact that a program of study is” an epistemic region” that” is constantly challenged from both inside the institution and form outside” (p. 3). This epistemic region is characterized by a particular way of understanding and promoting knowledge and certain specific accents and goals in the effort of education. These will influence the way the learning outcomes will be understood, selected and targeted.

the institutional general orientation and mission as well as the institutional culture. Adopting the learning outcomes principle may orient the institution in creating an outcome-based education with its advantages and with its obvious limitation, out of which the most difficult to manage would be a certain limitation of liberty in educational decisions (Erikson & Erikson, 2019; Sweetman, 2019b).

In front of these challenges, the higher education institutions some solutions are advanced. Sweetman (2019a) and Erikson and Erikson, (2019) put forward the idea of developing a culture of collaboration and communication between faculty members. This could be a vector for encouraging common learning outcomes writing and a cohesive teaching and evaluation approach. In this context, a special attention must be given to preserving teachers’ academic freedom by avoiding putting the administrative practices as a first priority, by promoting a culture of reflective teaching (Havnes & Prøitz, 2016; Sweetman, 2019a). Students’ involvement (Erikson & Erikson, 2019; Sweetman, 2019a) as partners of communication and improvement could help better focusing of students, as beneficiaries of the study programs. This approach could imply certain subsequent decisions regarding the moments and documents through which students will become aware of the intended learning outcomes, the way they are presented to them, documenting the way they perceive the intended outcomes and ways to involve students in learning outcomes writing, evaluation and revision.

The consulted articles and guides gave us an image on the solutions undertaken in higher education institution for learning outcomes norm implementation. It is frequently used for Curriculum design and development. In the effort of guiding their writing and use of learning outcomes, certain theoretical models are used. The most frequently quoted is the revised Bloom taxonomy for the cognitive domain (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001), the Constructive alignment model (Biggs, 2003) / Backwards design – Understanding by design model (Wiggins et al., 2005), and the SOLO (Structure of the Observed Learning Outcomes) taxonomy of Biggs and Collis (2014). There is a clear need for what Ure (2019) named an ‘organizational instrument’ (Ure, 2019) that is commonly understood and consistently used in curriculum development as well as in guiding the teaching, learning and evaluation.

As a result of the analyses of the existing state of learning outcomes implementation in higher education as well as of the observed need for a guiding model for a relevant enactment of learning outcomes, in the following we advance a set of anchors for a possible framework in guiding the use of learning outcomes in higher education.

At the level of philosophy of the approach, the key elements are:

establishing an agreed understanding for the concept of learning and for the term learning outcomes;

reflecting and taking decisions on the institutional culture. The promoted institutional culture has implications for the way learning outcomes approach is accommodated: quality assurance and accountability as well as generating new knowledge and creative approaches to teaching.

decisions regarding the levels at which learning outcomes are defined. Two categories of decision seem relevant:

administrative levels and decision-making bodies involved in the formulation of learning outcomes.

curriculum levels: the study program levels at which learning outcomes are defined. These decisions have implications for the type of intended study results and their formulation in rather terms of processes or of products, in a rather open or close-ended formulation.

identification and use of learning outcomes. This last aspect Taxonomies of cognitive processes that include benchmarks for writing relevant and rigurous learning experiences. Starting from the existing recommendations we support the use of two emerging models of learning behavior:

Willard Daggett’s Frameworkin learning (2016)

Karin Hess’s(Hess et al., 2009)

Both taxonomies are constructed on the existing and well-known taxonomy pf Benjamin Bloom and are intended to give Bloom’s taxonomy some depth. They can help not only with the formulation of learning outcomes, but with creating rigorous and relevant contexts for their assimilation and evaluation.

The (Daggett, 2014) combines two dimensions for standards and student’s achievement: a thinking continuum, that shows the well-known increasingly complex thinking behaviors presenting the revised Bloom taxonomy. The second continuum is the application continuum that describes context for putting knowledge to use. The model states the importance of exercising and proving the higher order acquisitions in an application context that is closer to the real world that is often unpredictable. The model has four quadrants that can be seen as spaces for knowledge acquisition training and validation. The question is where do our students spend most of the time?

The second model – Cognitive rigour matrix-, created by Hess et al. (2009) and largely developed and explored by Karin Hess (2014), also starts form the Blooms revised taxonomy and states that different cognitive behaviors receive different meanings when they are performed at different levels of knowledge depth. The most desirable performances would be the ones that prove strategic and extended knowledge. Yet, the less advanced behaviors are very important as building blocks for the more refined ones (Hess, 2014). Moreover, this approach is in tune with what we understand by competence. The model gives depth to Bloom’s taxonomy in terms of level of information processing. It can be used for both the formulation of relevant learning outcomes at the level of courses and study modules and for guiding the curriculum development in the light of learning outcomes.

We articulated the three types of anchors in a cohesive theoretical model.

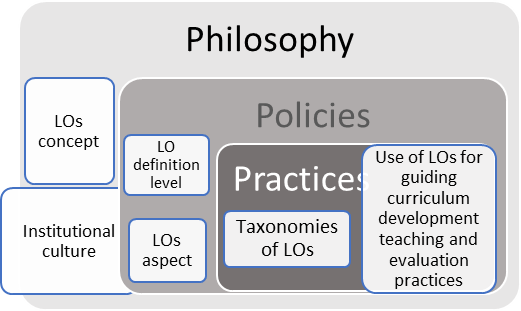

The three types of decisions and actions, the philosophical one, the policy one and the practices one, must be seen in a nested connection (as presented in the figure above – figure 1). Conceptions and believes always inform the practice and in the case of learning outcomes principle, the action of their use is dependent on the meaning given to the concept and the way this meaning is promoted in the institutional culture, at the level of educational policies and regulation and at the practical level of educational design, teaching and evaluation.

Conclusion

There is a critical mass for change in higher education in the light of improving its transparence, accountability and relevance. Adoption of learning outcomes principle as a philosophical, policy and practical orientation may be a solution in this respect. Higher education institutions constantly try to find solutions for accommodating this need for change and growth. Research on the topic offers mixed proves, but supports the need for an internal coherence in defining institutional philosophy, own policies and adequate practices in adopting the learning outcomes-based study programs.

References

Anderson, L., & Krathwohl, D. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Addison, Wesley Longman.

Biggs, J. (2003). Aligning teaching and assessing to course objectives. Teaching and learning in higher education: New trends and innovations, 2(4), 13-17.

Biggs, J. B., & Collis, K. F. (2014). Evaluating the quality of learning: The SOLO taxonomy (Structure of the Observed Learning Outcome). Academic Press.

CEDEFOP (2017). Defining, writing and applying learning outcomes. A European handbook. https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/publications-and-resources/publications/4156

Curaj, A., Deca, L., & Pricopie, R. ed. (2018). European higher education area: The impact of past and future policies (p. 721). Springer Nature.

Daggett, W. R. (2014). Rigor/Relevance Framework®: A guide to focusing resources to increase student performance. International Center for Leadership in Education. Retrieved from http://leadered.com/pdf/Rigor_Relevance_Fr amework_2014.pdf

Erikson, M. G., & Erikson, M. (2019). Learning outcomes and critical thinking–good intentions in conflict. Studies in Higher Education, 44(12), 2293-2303.

European Commission (2021). Helping people to develop skills throughout their lives. https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1511&langId=en

European Council (2017). Council Recommendation of 22 May 2017 on the European Qualifications Framework for lifelong learning and repealing the recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2008 on the establishment of the European Qualifications Framework for lifelong learning (2017/C 189/03). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/RO/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32017H0615(01)&from=EN

European Skills Index (2020). Country Pillars Romania. https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/tools/european-skills-index/country/romania?y=2020

Halasz, G. (2017). The spread of the Learning Outcomes approaches across countries, subsystems and levels: A special focus on teacher education. European Journal of Education, 52, 180–912.

Hansen, J. B., Gallavara, G., Nordblad, M., Persson, V., Salado-Rasmussen, J., & Weigelt, K. (2013). Learning outcomes in external quality assurance approaches: Investigating and discussing Nordic practices and developments: Nordic quality assurance network in higher education.

Havnes, A., & Prøitz, T. S. (2016). Why use learning outcomes in higher education? Exploring the grounds for academic resistance and reclaiming the value of unexpected learning. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability Issue 3/2016.

Hess, K. (2014). DOK an Hess Cognitive Rigor Matrices. https://www.karin-hess.com/free-resources

Hess, K. K., Jones, B. S., Carlock, D., & Walkup, J. R. (2009). Cognitive Rigor: Blending the Strengths of Bloom's Taxonomy and Webb's Depth of Knowledge to Enhance Classroom-Level Processes. Online Submission.

Lennon, M. C. (2018). Learning Outcomes Policies for Transparency: Impacts and Promising Practices in European Higher Education Regulation. In European Higher Education Area: The Impact of Past and Future Policies (pp. 527-546). Springer, Cham.

Muller, J., & Young, M. (2014) Disciplines, skills and the university. Higher Education, 67(2), 127-140.

Prøitz, T. S., Havnes, A., Briggs, M., & Scott, I. (2017). Learning outcomes in professional contexts in higher education. European Journal of Education, 52(1), 31-43.

Randahn, S., & Niedermeier, F. (2017). Quality Assurance of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education Institutions. Module 3. In Randhahn, S., & Niedermeier, F. (Eds.), Training on Internal Quality Assurance Series. Duisburg/Essen: DuEPublico. DOI:

Sweetman, R. (2019a). Exploring the enactment of learning outcomes in higher education: Contested interpretations and practices through policy nets, knots, and tangle. PhD theses at University of Oslo

Sweetman, R. (2019b). Incompatible enactments of learning outcomes? Leader, teacher and student experiences of an ambiguous policy object. Teaching in Higher Education, 24(2), 141-156.

Tam, M. (2014). Outcomes-based approach to quality assessment and curriculum improvement in higher education. Quality assurance in education, 22(2), 158-168. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Ure, O. B. (2019). Learning outcomes between learner centredness and institutionalisation of qualification frameworks. Policy Futures in Education, 17(2), 172-188.

Wiggins, G. P., Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. ASCD.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

23 March 2022

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-955-9

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

2

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-803

Subjects

Education, Early Childhood Education, Digital Education, Development, Covid-19

Cite this article as:

GLAVA, A. E. (2022). A Framework For Defining Learning Outcomes That Support Relevant Higher Education. In I. Albulescu, & C. Stan (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development - ERD 2021, vol 2. European Proceedings of Educational Sciences (pp. 50-58). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.22032.5