Abstract

The helping relationship represents the main scenario in which the educational counselor and tutor act to manage and successfully develop the dialogue with the disabled student-athlete in the university and the school. The dialogue occurring in this relation becomes a "helping interview." One of the prominent scholars who studied the helping interview in the framework of the helping relationship was the father of humanistic psychology, Carl Rogers. The helping interview is challenging to accomplish because it needs a specific preparatory exercise. The helping interview is always influenced by the type of subjects it is aimed at and its context. Currently, there are few studies on the topic of educational counseling for disabled college student-athletes. The purpose of our study is to review the existing scientific literature on counseling for disabled student-athletes in universities and to explore the issues involved. To better understand these issues, we conducted a case study with some disabled student-athletes we interviewed. We transcribed the interviews, analysed the qualitative data collected, and processed them using qualitative analysis software. The analysis allowed us to identify, through the drawing of a conceptual map, the needs of student-athletes. Moreover, it has allowed us to draw up a list of specific questions that, in light of the Rogerian dialogic approach to helping relationships, can be used by a counselor for the educational counseling of student-athletes both in the university and school.

Keywords: Carl Rogers, disability, helping relationship, student-athlete

Introduction

Counseling and tutoring for student-athletes with disabilities are always highly complex actions. Counselors, tutors, and society often misunderstand disability because, in general, they tend to view disability as an adverse event and as something undesirable. However, this is not necessarily the experience or belief of many people with disabilities (Dunn & Brody, 2008), for whom the latter sometimes represents the normal condition by which they are in the world and perceive themselves (Wright, 1991).

Counselors and university tutors assisting disabled student-athletes and their families need to understand the experience and process that leads to society's perception of disability. A lack of adequate training in this area can limit the understanding and effectiveness of their intervention. Their intervention consists primarily of providing help to disabled student-athletes to respond to the problems generated by their disabilities successfully and creatively, using them in a positive, ameliorative, and transformative way (Foley-Nicpon & Lee, 2012).

People who are not familiar with disability always focus on the negative aspects of having or living with a disability and tend to identify the disabled person primarily through this characteristic, failing to go beyond it (Smart, 2009). These negative attitudes, such as beliefs, convictions, and prejudices, also affect university tutors and counselors. Even if counseling professionals and tutors are well disposed of (as it is natural given their work) toward such problems, they can be subject to the effect of social and historical beliefs related to disability and may, without realizing it, contribute to the perception of disabled people as ill, weak, incomplete and in need of care.

This attitude, in turn, harms the relationship between the counselor/tutor and families of disabled student-athletes. Moreover, most of the time, universities usually do not provide tutors and counselors with adequate training about athletes' specific needs and their perception of disabilities. This is serious and effectively amounts to not providing adequate tutorship and care to disabled student-athletes. For these reasons, counselors and tutors must reflect on their own beliefs and expectations about disability, know the types of disabilities, and communicate with their tutees effectively.

In their approach and interaction with disabled student-athletes, counselors and tutors must:

• use appropriate language to describe the student-athlete and their disability;

• identify personal and social barriers encountered by the disabled student-athlete;

• build a theoretical framework from which to understand disability adaptation from the student-athlete point of view;

• learn specific counseling and tutoring techniques to improve the effectiveness of the helping interview;

• always observe basic counseling and tutoring principles when working with disabled student-athletes.

The importance of dialogue and understanding to remove barriers

In this context, language, regardless of the intent with which it is used, is a potent tool for counseling and tutoring disabled athletes. It can be used for elevating or degrade someone depending on how it is used (Stuntzner, 2008), and for conveying attitudes and values toward others (Smart, 2009). Of particular importance is awareness and consideration of the terminology used to describe and refer to traditionally marginalized groups, including people with disabilities. Incorrect or inaccurate words can encourage and promote, even if unintentionally, distorted, and negative perceptions and feelings toward people with disabilities. Some of these words are, for example, "disabled," "suffering," "afflicted," "victim," "handicapped," "crippled," and "wheelchair-bound" (Titchkosky, 2001). In addition, language and repeated use of harmful and exclusionary words can influence how people view themselves, particularly when such experiences are internalized.

The language others use to refer to disability can be influenced by how disabled people view themselves and how they experience disability and interpret it from the outside. Many scholars of disability issues (Siller, 1976; Smart, 2009) since the 1970s have highlighted how negative perspectives toward other people's disabilities are about themselves, not about people with disabilities. The scientific literature and counseling research emphasize the presence of negative attitudes toward disability that can consist of:

1) in physically distancing themselves from people with disabilities because of their discomfort;

2) in increasing anxiety about the prospect of dealing and communicating with a person with a disability;

3) in attributing negative personality traits to people with disabilities;

4) in being afraid that the same thing - an impairment, a disability - could happen (or could have happened) to them. This increases and creates additional distance.

Counselors and tutors tutoring disabled student-athletes should be aware of the impact of cultural, historical, and social perceptions about disability and how all these factors affect social beliefs (Rubin & Roessler, 2008). In addition, they have a professional responsibility to be aware of the words they use when referring to people with disabilities and their potential impact.

Counselors and tutors should be encouraged to learn and think more about the appropriate terminology to indicate disability, including using the "first person." In most cases, "people with disabilities" can be referred to as such or called – better said – "differently-abled." No doubt that a more suitable and appropriate way to refer to people with disabilities is to call them by their name. However, this is often not what occurs (Andrews et al., 2019).

In all of these cases, the focus is on recognizing and valuing the fact that each disabled student-athlete, first and foremost before being a student and an athlete, is a person with many qualities coming from their disability (or rather, "different ability"). Disability is only one of their characteristics.

Complicating this is that each disabled student-athlete has their preferences and ways of identifying and describing themselves. In these cases, counselors and tutors should be sensitive to the terms used by student-athletes. Counselors and tutors should ask the student-athletes with a disability under their supervision about their personal preferences and how they would like to be called. For counselors and tutors of disabled student-athletes is of particular relevance:

1) to identify the primary barriers they find in schools and universities;

2) to examine how identified obstacles and barriers inhibit their activities and duties as both students and athletes or prevent them from addressing the problems they face more positively;

3) to explore what problems are within their control, overcome them, and generate change;

4) to determine strategies that can be used to address and overcome problems.

The concept helping relationship

The helping relationship represents the main scenario in which the tutor and the counselor act to manage and successfully conclude the dialogue with the disabled student-athlete. This dialogue becomes, in this relationship, the helping interview. Without pretending to give here an exhaustive and complete definition of the "helping relationship," we will try to summarize the concept, considering what has been written by authors such as Rogers, Dietrich, and Madrid Soriano.

Carl Rogers derived his helping relationship by borrowing it from humanistic psychology, counseling, emotional intelligence, cognitive psychology, and problem-solving training. For Rogers (1961), the helping relationship is that relationship in which one of the participants seeks to bring about, on one or both sides, a better appreciation and expression of the person's latent resources and more practical use of them.

For Dietrich (1986), however, the helping relationship is one in which the helper seeks to stimulate and enable the subject's self-help. The benevolence and friendly attitude of the counselor toward the subject does not mean that the counselor makes decisions on the subject's behalf, establishes the subject's life path, relieves the subject of all responsibility, and removes all obstacles from the path. Instead, this relationship seeks to create a climate and initiate a dialogue with the subject that allows them to clarify their problems, free themselves, and find resources for conflict resolution on their initiative and responsibility (Isidori, 2005).

Finally, Madrid Soriano (2004) states that a helping relationship is one whose purpose is to facilitate the growth of the person's latent (or relatively latent) capacities in a problematic situation. At the very base of all is a positive view of personal capacities to grow and deal positively with their conflicts.

The three positions of the authors mentioned above highlight the fundamental role played by both pedagogy and psychology as sciences contributing to the orientation towards "positivity," the helping relationship, and the active role attributed to the person asking for help.

According to Madrid Soriano (2004), there is always a purpose in the helping relationship. The people who participate bring different elements and seek outcomes based on the mutual need to be accepted, appreciated, and meet their contingent needs within meeting vital needs.

Within the helping relationship, people gain or increase awareness of their current problems. They address their present and future problems by seeking different possibilities for solutions. They learn to use clear communication and to ask for help if they need it openly; they learn new behaviors (by experiencing them in a safe environment) that may help them solve the problems encountered; they find a meaning to their current situation about their lifestyle (Di Fabio, 2003).

To all these objectives, it must be added that both the counselor and tutor receive as a benefit learning and being helped to acquire more relational experience by living a situation that allows them to self-analyze and increase their self-knowledge. This will be helpful to them in dealing better with future helping relationships.

Rogers (1961), to ensure a quality helping relationship that adequately meets the goals above identified, has stressed the importance of at least three elements on the part of the counselor which are fundamental to any helping relationship:

: that is to say, an attitude that predisposes one to grasp the feelings, emotions, desires, interests, and needs of the other person to understand their experience. This is done without confusing our feelings and perceptions with those of the other person.

: that is, acceptance of the other person as they are. This provides a safe environment for the person to express themselves and find new and healthier behavior patterns. This skill requires sensitivity and the ability to objectively perceive and assess the other person's needs and respond to them appropriately and respectfully.

: a style of behaviour that involves showing up as we are. It requires personal maturity and an awareness of one's abilities and weaknesses.

In addition, there are different styles of helping relationships. According to Bermejo (1998), the helping relationship can be either problem-centred or person-centred. In the first case, the counselor identifies with the person's problem or situation without considering the subjective aspects with which the person experiences the problem. In the second case, the counselor pays attention primarily to the person and how they experience the problem. He considers the person as a "whole".

Also, depending on the counselor’s use of their knowledge, the helping relationship may be directive or facilitative. If it is a directive relationship, the counselor is the expert, and they will use a set of behaviours and techniques that will persuade the person being helped to act as guided by them. If, on the other hand, the relationship is "facilitative," the counselor will resort primarily to the skills/resources of the person helped, seeking to transform the person with difficulty into a sort of "own researcher," making him or her aware of his or her problems and possible solutions (Carkhuff, 1994).

All styles can be effective and achieve the goals they aim to. It all depends on whom the counselor is dealing with and what the circumstances require at any given time (Maulini, 2018). Therefore, a good counselor should know how to move between styles depending on the situation. This should be done without losing sight of the goals and purpose of the helping relationship.

Problem Statement

The helping relationship has four main phases. Madrid Soriano (2004) indicated that it is essential to note that it is difficult to define the exact moment when one phase ends and the next begins. Moreover, not all phases occur in a helping relationship. There may be blockages on one of the parties involved. The four phases which we present here shortly are articulated as follows.

1): this is when the first contact between the counselor and the person/client occurs, and the foundation of the relationship is laid. The counselor takes the initiative first by introducing themselves, communicating their responsibilities and agenda, and guiding the client by providing a framework. This is what is called "framing." The client is asked what they expect from the relationship, and the first specific goals are established.

2): in this phase, an assessment of the person's needs is made. The problems are assessed, and their limitations and possible causes are defined. From this stage onwards, the client actively participates. The specific objectives and methodology are also definitively agreed upon at this stage.

3): in this phase, the counselor encourages the client to achieve the agreed-upon goals regarding improving their health or resolving their situation, helping them to set their realistic expectations, assessing and encouraging them to take responsibility in the problem-solving process.

4): in this phase, the counselor-client relationship has ended. Emotions related to the end of the relationship are gathered, made explicit, shared, and the farewell happens. Goals achieved with the client are reviewed, and self-care is stimulated and encouraged. The main goal at this stage is to generalize what has been learned to transpose it to other life situations.

Based on these studies, there is no doubt that counselors and tutors dealing with disabled student-athletes may also use techniques that address managing complex emotions, redefining self-concept and personal identity, learning self-advocacy techniques, and integrating learned skills to become more confident. To better understand and help people with disabilities, counselors and tutors must:

- be aware that the negative experiences expressed about disability are real;

- always consider the effects that labels may have on their student-athletes;

- treating their student-athletes as human beings rather than as disabled;

- have an awareness of their attitudes and biases that can affect the helping relationship and the effectiveness of counseling and tutoring;

- be aware of how people with student-athletes describe themselves;

- respect the fact that student-athletes know their bodies;

- acquire the training and preparation necessary to serve as a counselor and tutor with student-athletes effectively;

- always pay attention to the abilities and strengths of student-athletes by always incorporating them into the helping strategies provided by counseling and tutoring;

- recognize the fact that most student-athletes do not live their lives focusing only on their disability and limitations (no doubt sport is an effective means to help them focus on other abilities, skills, and competencies);

- identify counseling and tutoring interview topics that make them uncomfortable;

- be open to the shared experiences within the helping relationship gained through counseling.

Research Questions

Also, several techniques can be offered to improve the effectiveness of counseling for people with disabilities. These techniques and strategies aim to focus on changing a person's thoughts, feelings, and behaviours concerning themselves and others. Some approaches have been studied empirically and have been shown to reduce negative thoughts and emotions (i.e., forgiveness and self-pity). Therefore, they have been referred to as essential skills for living well with a disability (i.e., resilience, self-advocacy, self-esteem, life skills).

These approaches aim to change the way people think, feel, or act in situations related to their disability. Forgiveness, self-compassion, and resilience are three constructs that have been empirically studied. More specifically, forgiveness and self-compassion have been shown to reduce negative emotions and improve a person's overall well-being (Neff, 2011). Both constructs and approaches have much relevance to the lives of people with disabilities because of the high number of negative experiences and treatments these people face. Resilience is a skill that has much relevance to the needs and problems of people with disabilities. Forgiveness, resilience, and self-compassion can be used to show clients with disabilities how to overcome, adapt, and accept their selves about their disability by coming to a state of well-being (Nierenberg et al., 2016).

Based on these premises, we wondered whether it was possible to build an authentic relationship that could go beyond the stereotypes and misunderstanding of disability by taking inspiration from Carl Rogers' model of humanistic communication model; that is to say, according to the Rogerian dialogic perspective on counseling and tutoring.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of our study was to review the existing scientific literature on counseling for disabled student-athletes in universities and better define the key elements which allow the development of a more effective dialogue between tutor/counselor and the student-athlete within the context of an authentic helping relationship.

Research Methods

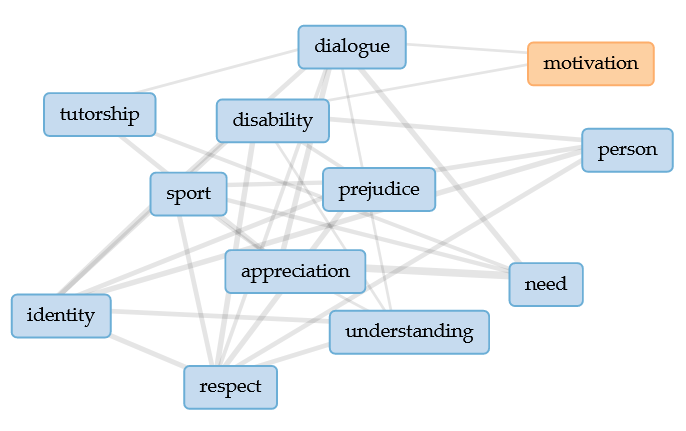

We conducted a case study (based on three focus groups) with some disabled student-athletes we interviewed to understand these issues better. The sample of our research was composed of 9 individuals taken from the Universities whose researchers participated in this study). We transcribed the interviews, analysed the qualitative data collected, and processed them using qualitative analysis software (Voyant Tools). Through an interpretation of words frequency, the analysis allowed us to identify the needs of disabled student-athletes regarding the quality of communication between them and their tutors in tutoring them and in the helping relationship.

Findings

From the study we have conducted, it has emerged the importance for the counselor and the tutor to be open and prepared to listen to the disabled student-athlete. The analysis conducted through the text analysis has stressed the specific needs expressed by student-athletes regarding the communication and tutoring desirable model with their tutors and counselors. Also, what has emerged from the analysis is that not only the map of needs seen as priorities by student-athletes develops according to Maslow's theory of motivation and personality (1970), but also that only a dialogue developed in an authentically Rogerian perspective can make effective and make more human a tutorship relationship.

Questions to initiate a helping relationship in the Rogerian perspective

Moreover, the text analysis has allowed us to draw up a list of specific questions that, in light of the Rogerian dialogic approach to the helping relationship, can be used by a counselor to educational counseling of student-athletes both in the university and school. These questions are as follows.

- How can I be in a way that the disabled student-athlete perceives me as trustworthy, "consistent," and secure in a deep sense? Gaining the other person's trust does not require rigid stability but involves being sincere and authentic. The term "consistent" is meant to describe the way of being that one wants to achieve. This means being able to understand any feeling or attitude that one feels at any given moment. When this condition is met, one is an "integral" and "holistic" person and can be deeply authentic in oneself. This is the reality that inspires trust in disabled student-athletes.

- Can I be expressive as a person to communicate to the disabled student-athlete that I am an unambiguous person without misunderstanding? Indeed, accepting themselves and showing themselves to the other person as they are, is one of the most challenging tasks for counselors and tutors; this can rarely be accomplished entirely.

- Am I able to feel positive attitudes towards the disabled student-athletes: attitudes of affection, care, pleasure, interest, respect? We often notice in ourselves - and often in others - a particular fear of those feelings. We fear that we will be prisoners if we allow ourselves to feel such feelings toward other people. Others might make demands on us or disappoint us, and, of course, we do not want to take those risks.

- Can I be strong as a person to set myself apart from others? Can I firmly respect my feelings and needs, as well as those of the other? Am I in control of my feelings and able to express them as something that belongs to me? Am I able to not get depressed by any potential depression of disabled student-athletes?

- Am I confident enough to admit the individuality of disabled student-athletes? Can I let them be what they are: authentic or false, child or adult, desperate or full of confidence? Can I grant them the freedom to be? Or do I feel that the other should follow my advice, depend on me to some extent, or take me as a role model?

- Am I able to penetrate student-athletes personal feelings and their world and see how they experience it? Can I enter this world with a gentleness that allows me to move freely without destroying meanings that are precious to them?

- Can I accept the student-athlete as they are? Or rather, can I communicate this attitude? Or can I express it only conditionally, accepting some aspects of their feelings while rejecting others openly or secretly?

- Can I conduct myself in the helping relationship with the necessary feel so that my behavior is not felt as a threat?

- Can I free the student-athlete from the threat and fear of external evaluation?

- Can I address the disabled student-athlete as a person who exists in their own right and with their own identity in the transformation process, or will my background and theirs limit me? If I treat them as immature children, ignorant students, each concept that I attach to the relationship will limit what I can be in it. If I look to the disabled student-athlete as somebody imprisoned in their diagnosis, categorized, and shaped by their past, I will help confirm this unreasonable assumption. Instead, if I accept the relationship as a transformation process, I will help confirm and realize the potential of the disabled student-athlete.

These questions are strictly connected to the needs student-athletes would want to satisfy about the quality of communication within the relationship with their tutors. This means that there is no possibility of starting an authentic relationship between a tutor/counselor and a disabled student-athlete if, before beginning the relation, the tutor and the counselor do not explore their prejudices and stereotypes towards disability and take aware of their role of authentic people committed to creating an authentic dialogue with other people.

Conclusion

Answering the ten questions we have indicated can be helpful for the counselor and the tutor both in the preparatory phase and in the live dialogue with the disabled student-athletes. It is undoubtedly a complex exercise that implies the acceptance of a challenge. This challenge is the very essence of counseling and tutoring disabled student-athletes in the university. It consists of dealing with a possible transformation that concerns the student-athlete and the counselor/tutor themselves as a person and as a helping relationship professional, independently of the wealth of knowledge, methodologies, and techniques they face the helping relationship.

Disability is an experience usually not understood in its fullness by most people who do not experience it, including counselors and tutors, who do not frequently work with this type of student in schools and Universities. To change this trend, counselors and tutors need to open themselves up to the possibility of learning about and deepening their understanding of disability by listening deeply to the voices of disabled student-athletes, understanding their perspective on the disability itself. This disability, however, must be approached by the counselor and tutor in itself, without building models of comparison and always taking into account that every human being is what he or she is (i.e., is always originally a "self" that is never the same as "another") thanks to the particular way in which they reveal themselves in the world.

This mode is made possible because each person has a difference within himself/herself that builds his/her identity and differentiates him/her from others. Diversity is a resource for the science of counseling and tutoring because it provides counselors and tutors with an opportunity to learn and train themselves. It can be, in fact, an opportunity for enrichment since, through confrontation with diversity, counselors and tutors can broaden their horizons of meaning, enhance their ability to interpret the world, and, therefore, also their intelligence. The tutor and counselor working in schools and Universities can benefit the school and the university itself, which, through teachers, can improve the quality of teaching. Disability - or rather, the disabilities of student-athletes - in fact, at first appearing to be an obstacle to learning and playing the sport, later invites tutors and counselors to put themselves entirely at stake, formulating specific intervention strategies. Disability at school and university activates a series of cognitive and intervention strategies that can be seen as actual permanent problem-solving actions that continuously improve overall teaching quality (Zagelbaum, 2014).

Moreover, the encounter with disabled student-athletes by a counselor or a tutor stimulates in them the socio-cognitive conflict that, in turn, can generate a higher level of knowledge. A problem that goes beyond the usual mental strategies of a person can often generate the organization or reorganization of new and more effective learning strategies that, through processing, lead the subject to advancement in a higher stage of knowledge (Sánchez Pato et al., 2017).

Counseling and tutoring aim to enhance the originality of the exceptionality of the experience of disability in student-athletes. The effort to understand different abilities/diversity will benefit not only the disabled student-athletes but also counselors and tutors, who will thus be able to grow from a human and professional point of view, and the helping relationship itself as a practice of improving the human condition aimed at promoting the well-being and integration of people

Acknowledgments

This study has been developed within the research activities of Erasmus+ Project PARA-LIMITS -Dual Career of Student-Athletes with Disabilities as a Tool for Social Inclusion (622213-EPP-1-2020-1-ES-SPO-SCP).

References

Andrews, E.E., Forber-Pratt, A.J., Mona, L.R., Lund, E.M., Pilarski, C.R., & Balter, R. (2019). #SaytheWord: A disability culture commentary on the erasure of “disability”. Rehabilitation psychology, 64(2), 111.

Bermejo, J. C. (1998). Apuntes de relación de ayuda [Notes on helping relationship]. Editorial Sal Terrae.

Carkhuff, R. (1994). L'arte di aiutare [The art of helping]. Trento: Erickson.

Di Fabio, A. (2003). Counseling e relazione d'aiuto [Counseling and helping relationship]. Firenze: Giunti.

Dietrich, G. (1986). Psicología general del counseling [General psychology of couseling]. Barcelona: Herder.

Dunn, D.S., & Brody, C. (2008). Defining the good life: Following acquired physical disability. Rehabilitation Psychology, 53(4), 413-425.

Foley-Nicpon, M., & Lee, S. (2012). Disability research in counseling psychology journals: A 20-year content analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59(3), 392-398.

Isidori, E. (2005). Ermeneutica e pedagogia della persona. Dal dialogo alla cura [Hermeneutics and pedagogy of the person. From dialogue to the cure]. Roma: Aracne.

Madrid Soriano, J. (2004). Los procesos de la relación de ayuda [Processes of helping relationship]. Bilbao: Desclée de Brouwer.

Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality. Harper & Row.

Maulini, C. (2018). Il counselling educativo nella dual career degli atleti-studenti [The educational counseling in the dual career of student-athletes]. International Journal of Sports Humanities, 1(1), 63-70.

Neff, K. D. (2011). Self-compassion: Stop beating yourself up and leave insecurity behind. Harper Collins.

Nierenberg, B., Mayersohn, G., Serpa, S., Holovatyk, A., Smith, E., & Cooper, S. (2016). Application of well-being therapy to people with disability and chronic illness. Rehabilitation Psychology, 61(1), 32-43.

Rogers, C. R. (1961). On becoming a person: a therapist's view of psychotherapy. Houghton Mifflin Company.

Rubin, S. E., & Roessler, R. T. (2008). Foundations of the vocational rehabilitation process. (6th ed.). Austin, TX: PRO-ED.

Sánchez Pato, A., Isidori, E., Calderón, A., & Brunton, J. (2017). An innovative European sports tutorship model of the dual career of student-athletes. UCAM, Catholic University of Murcia.

Siller, J. (1976). Attitudes toward disability. In H. Rusalem, & D. Malikin (Eds.), Contemporary vocational rehabilitation (pp. 67-79). New York University Press.

Smart, J. (2009). Disability, society, and the individual. (2nd ed). Austin, TX: PRO-ED.

Stuntzner, S. (2008). Comparison of self-study, on-line interventions to promote psychological well-being in people with spinal cord injury: A forgiveness intervention and a coping effectively with spinal cord injury intervention. (PhD Thesis, University of Wisconsin: Madison, 2007).

Titchkosky, T. (2001). Disability: A rose by any other name? “People-first” language in Canadian society. Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue canadienne de sociologie, 38(2), 125-140.

Wright, B. A. (1991). Labeling: The need for greater person-environment individuation. In C. R. Snyder & D. R. Forsyth (Eds.), Handbook of social and clinical psychology (pp. 569-587). New York: Pergamon Press.

Zagelbaum, A. (2014). School counseling and the student athlete. New York: Routledge.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

23 March 2022

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-955-9

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

2

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-803

Subjects

Education, Early Childhood Education, Digital Education, Development, Covid-19

Cite this article as:

Isidori, E., Fazio, A., Magnanini, A., Sánchez-Pato, A., Martino, M. D., & Sandor, I. (2022). The Educational Counseling For Disabled Student-Athletes And The Rogerian Perspective. In I. Albulescu, & C. Stan (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development - ERD 2021, vol 2. European Proceedings of Educational Sciences (pp. 302-312). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.22032.29