Abstract

Most components of traditional classroom education need to be successfully transferred to the online environment so that learning is fully satisfactory. Even if the asynchronous way of conducting classes is a feature of online classes, in the current, uncharacteristic situation, a combination of synchronous-asynchronous methods was needed to successfully complete the complete and complex teaching-learning-assessment process. The learning experience has undergone an unplanned transition and many things have been achieved along the way, even though the example of online - distance learning has been present for a while, it had to be adapted to be satisfactory for all ages. Insufficient training by all participants in the educational act made this transition not necessarily a benefit, being recorded many syncope and inconveniences created by lack of equipment or even lack / quality of the Internet. Emotional health is the ability of a person to accept and manage feelings through challenge and change. Through these practices, children will be able to benefit from a permanent and balanced emotional health. Emotional health includes both emotional intelligence and emotional regulation and is present when the subjective experience of emotions is appropriate over a sustained period. As adults, educators and parents are responsible for ensuring a balanced emotional development of children, especially when external factors can creep in and negatively influence children's emotional development. The aim of the current study was to explore the perspective of parents and teachers on child well-being and emotional health using an investigative method.

Keywords: Asynchronous, emotional health, e-learning, emotions, synchronous

Introduction

The way that people manage their thoughts and emotions during a period of time determines their emotional health. It is not something that we measure, but rather it helps in everyday activities and even life crises like emotional surges and health risks. Emotional health comprises of components that are meant to be kept in check in order for the individual’s life to be happy, both personal and professional. How people manage their emotions determines the way in which they interact with others on a daily basis. This is especially visible in children that tend to be less body able to manage intense emotions and stress. Emotional health, along with psychological and social health, comprises the mental health of an individual (Keyes, 2014). In today’s scenario emotional health is key in keeping problems in perspective, feeling good about making decisions and having overall healthy relationships with their peers. In children this can be rather difficult especially when they are deprived from social interactions limited to only they closed family. Emotional regulation strategies require experience (Kobylińska & Kusev, 2019) and the more interactions they have the more skilled they will become in handling their emotions. Emotional health is defined by happiness, interest in life and overall satisfaction with life (Galderisi et al., 2015). A 2017 study of subjective well-being in children across nations revealed that freedom to choose and self are some of the most important factors in determining a countries overall subjective well-being in children (Lee & Yoo, 2017). The authors also found that when parents decide on the time spent by children during learning or leisure, the subjective well-being in children has been recorded as low.

At this point in time and in regards to the current world situation of the educational process there is an overwhelming importance for constructive family–school connections for the academic, social, and emotional learning of youth (Patrikakou et al., 2005). One important aspect that the author and colleagues underline in their paper is that, risk and resilience are not properties of children, but are distributed across systems and reside in the interactions, transactions, and relationships among the multiple systems that envelop children”. We can see that the way parents and teacher construct environments for children is crucial both in the relationship they develop with the children and consequently in the relationship that children form with their peers in school setting or other formal or informal settings. Schooling for children must be viewed systematically if we are to achieve academic, social, and emotional learning for all children enrolled in any educational setting.

In the online environment children’s behaviour can change and this depends on their previous encounters both in real life and online. Parental involvement with children from an early age has been found to equate with better outcomes (particularly in terms of cognitive development) (DCSF Publications, 2008). Parents have noticed that children’s externalized behaviour depends both on temperament and perceived rearing (Hiramura et al., 2010). The study also showed that both aggression and delinquency of children can be predicted by (1) paternal overprotection, (2) low maternal care, and (3) low maternal overprotection (respecting autonomy). It’s also important to note that parenting tasks differ for a child in the 1st grade than that of a child in 5th grade. The concerns of parents also differ in this regards, while they may not be interested in grade for primary school, this changes as the child grows-up, especially in middle school and high school, when parents can be overwhelming.

Statistics regarding parent’s commitment to school interactions have showed some interesting results, as it has been observed (Child trend data bank, 2013). In 2013, more than 90 percent of students in kindergarten through fifth grade had a parent who attended a meeting with their teachers, compared with 87 percent of middle‐school students, and 79 percent of ninth‐ through twelfth‐grade students. In the same year, 89 percent, each, of students in kindergarten through second grade, and students in third through fifth grade, had a parent who attended a scheduled meeting with a teacher, compared with 71 percent of students in middle school and 57 percent of students in high school. We can conclude that parents with younger children tend to be interested in the school setting more than those with older children. In summary, changes in parent–child relationships create new paradigms for interaction that affect when and how parents will respond to the behaviour of children during middle childhood. Although partly resulting from adaptations to developmental changes that have already occurred, these relational patterns also affect responses to further changes during and beyond middle childhood.

The digital strategy proposed by the European Committee offers policies for a better protection of minors in the online environment. This measure comes at a time where children spend not only leisure time on the internet, but also learning tasks also take place in the online setting. The Commission facilitates the "Alliance for the Better Protection of Minors in the Online Environment", a self-regulatory platform that brings together prestigious information and communication technology (ICT) and media companies as well as civil society to combat content and harmful behaviour. The platform focuses on 3 directions, as follows:

User-empowerment:

- Identifying and promoting best practice for the communication of data privacy practices;

- Providing accessible and robust tools that are easy to use and to provide feedback and notification as appropriate;

- Promoting users’ awareness and use of information and tools to help keep themselves safer online and of their responsibility and duty to behave responsibly and respectfully towards others and foster trust, at the same time promoting minor’s digital empowerment;

- Promoting the use of content classification when and where appropriate;

- Promoting the awareness and use of parental control tools.

Enhanced collaboration:

- Intensifying cooperation between ourselves and with other parties such as Child Safety Organisations Governments, education services and law enforcement to enhance best practice-sharing;

- Identifying emerging developments in technology such as connected devices and with the support of the Commission, engage with other parties who also have a role to play in supporting child safety online.

Awareness rising:

- Supporting the development of awareness-raising campaigns about online safety, digital empowerment, and media literacy through both ad hoc and ongoing initiatives;

- Promoting children’s access to diversified online content, opinions, information and knowledge.

Problem Statement

We are faced with problematic times and never before seen situations that have already taken a strike on our grasp of the unknown. We have been more than unprepared for the unfolding of the current setting of the online environment, not only we’re we underprepared, but also couldn’t grasp the danger or even benefit of the online learning process. We have used technology in the classroom as a distraction mostly, or only to present certain entertainment for children. Technology requires implementation and a creative eye in the process of creating a liberating and responsive society.

Research Questions

We wanted to reveal how the perceived emotional health is for children from both parents and teacher’s perspective.

Purpose of the Study

Both teachers and parents have been faced with challenges beyond their expectations. Their skills have been put to the test for the last 18 months. The online environment offers many challenges, both risky and rewarding. In order to know what is best for the children, teachers need to work out the best ways to approach synchronous and asynchronous teaching methods, the correct amount of information and use of methodology, the balance between online tasks to avoid overload. Parents have been put to the test and their trying to balance their work around the children’s schedule and it has been a challenge. The aim of the current study was to explore the perspective of parents and teachers on child well-being and emotional health using an investigative method.

Research Methods

Participants

Participants to this study were represented by parents and teachers. We had 146 parents who participated in the current study and have from one to three children or above. All the parents have children enrolled in the primary school system. Parents were between 25 and 55 or above (0.78%) as seen in table 1.

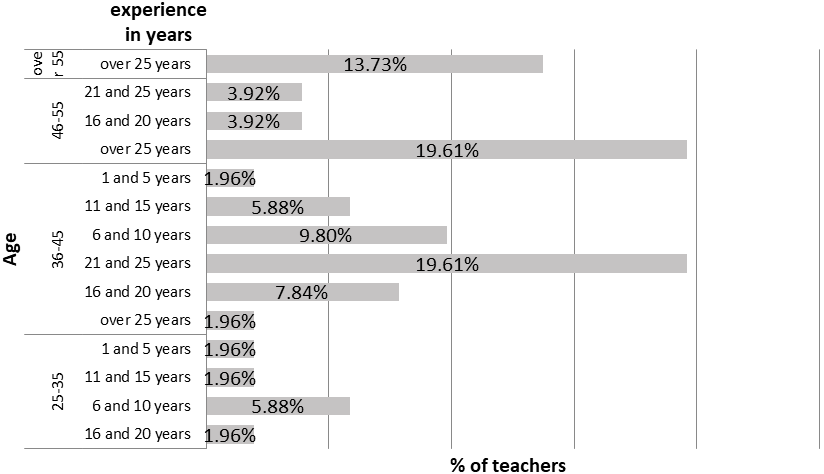

We have 51 teachers that participated in the current study with various levels of experience as can be seen in figure 1.

Design

We have design 2 survey questionnaires that were used for gathering information from the teachers and parents. The questionnaires for parents had 26 items on a five Likert scale that required their answer. For the teachers the questionnaire had 29 questions that required their answer. The questionnaires were delivered online using Google Forms, this way we tried to reach as may willing participants as possible. This was an easy way of delivery since parents and teachers have been in contact with this type of technique at least for the last 18 months. The items from the questionnaire focused on 4 directions: online environment, online behaviour (of children), distress (perceived for the children), and emotions (perceived by the children). The data collected was statistically processed and the findings are presented in the next section.

Findings

The data that we collected was devised according to the main participants: teachers and parents. Both groups have noted some important insight into their perceived data on children, both from home and from the classroom, either hybrid or onsite.

Teachers perspective

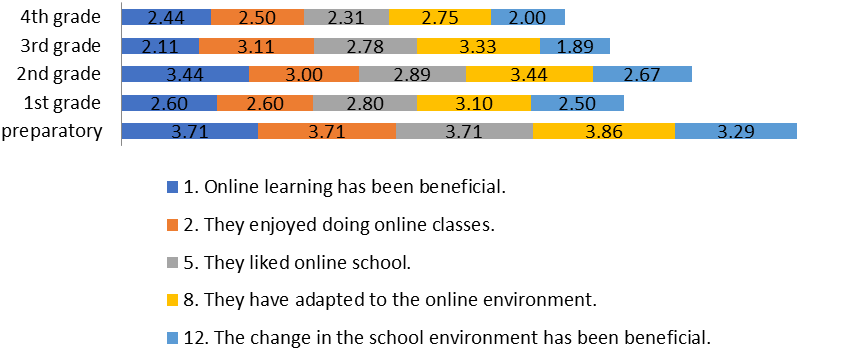

There was one aspect with right from the beggining of the pandemic situation that the teachers were faced with and that concerns the environment that they will continue to do their teaching. There was a continuous struggle to offer the best medium for the children in the online learning experience and this concerned online learning, lonline classes, the adaptabilty of online classes. We have the data presented in in Figure 2 below, where we can see that children in the 1st grade have a lower perceived benefit (M=2.60) from online learning than those from the 2nd grade (M=3.44) and preparatory grade (3.71), but also a grater mean than 3rd grade (M=2.11) and 4th grade (M=2.44). The mean for enjoyment of online classes has been above 2.50 for all grades, and we can also conclude that children from all grades have adapted to the online environment with the 2nd grade (M=3.44) being more adapted than all the others. Also teachers didn’t find beneficial the change in the school environment for most children.

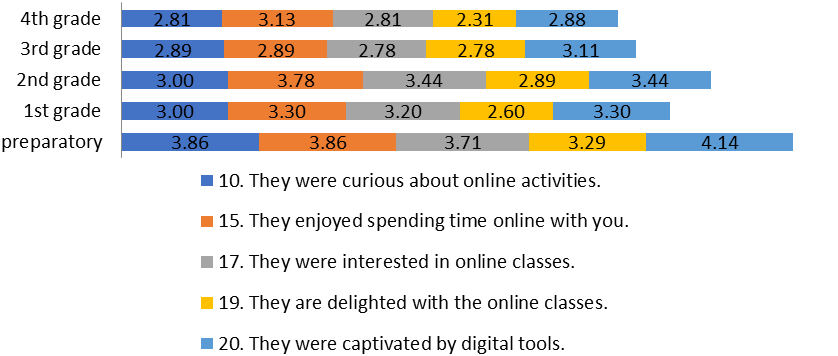

In figure 3 we are presenting the data regarding the perceived behaviour of children in the online learning settings. Here teachers have noted that children were curious about the online activities, also they presented interest in online classes and they were also captivated by the digital tools that the teachers has used in the e-learning setting for the classroom. We can observe that the teachers were more confident in the teaching tools they implemented and this might be why the children have perceived the learning experience better than the online environment seen above. Young children are eager to learn and in this new setting where new learning tools are implemented, children will enjoy the learning experience even more than before. Also the learning tools have changed with this shift of classroom environments, the lessons were filled with different interactions and afterschool work was reduced to a minimum. Lesson plans included more online learning games and activities that were very well received by the children. For the first time in primary school all the tablets and phones, laptops and computers were put to good use in the homes of these children. Government programs even invested in buying new digital platform to offer for free so that every child will have how to learn.

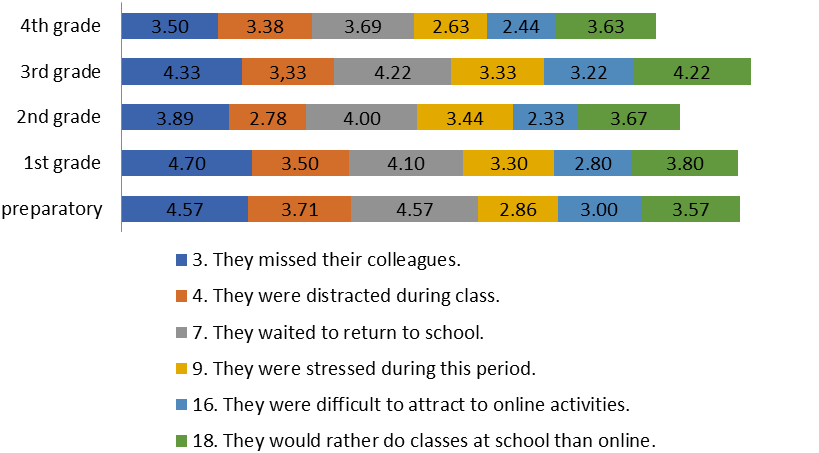

Considering the period that the children couldn’t attend classroom in person, teachers perceived some levels of distress concerning lack of peer interactions, missing school, difficulty in concentrating in the online classes for a prolonged period of time. As the data shows in Figure 4 we have high scores for all grades for the variables collected. The children mostly missed school (M=4.22 for 3rd grade) and would have rather return in the classroom for the learning process to continue. This was they would have interacted with their colleagues and their teachers.

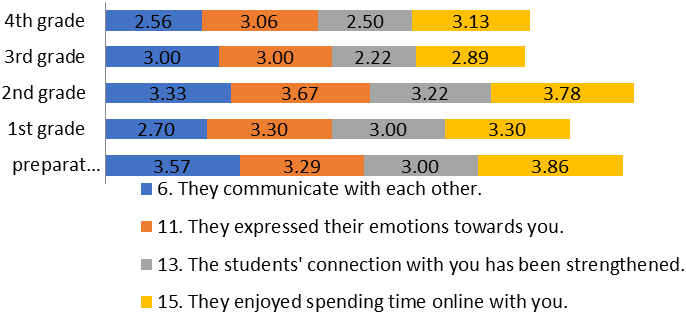

The way that teachers and children communicated in this period of lockdown has changed from the normal setting. Everybody was used to the old ways of face-to-face communication, where the chid raised their hand in the class to answer teachers questions or present a project. The online setting has rather changed this paradigm, children could raise their hands to answer, but the result wasn’t what expected for the situation. Since the communication had different factors to account for the children enjoyed their time spent online, because it was the only time they communicated with others that were not their family. Children also expressed their emotions towards their teacher in this setting (M=3.67 for 2nd grade). The teachers also perceived a strong connection with the children (M=3.22 for 2nd grade) as seen in figure 5 below.

Parents perspective

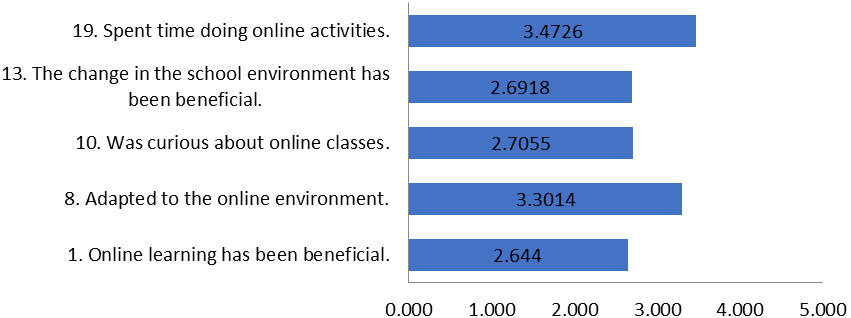

In the parents cases, the situations differed from that of the teachers, because the daily schedule of the parents changed in a sense that we recorded 20.55% of parents worked from home, 33.56% of them worked onsite, and 45.89% were in a hybrid working situation (from home and onsite). Since the children were at home all day, parents had to also adjust their working hours, find somebody from the family that they could supervise, either grandparents of older responsible siblings. This situation lasted for a very long time for all parents and they could only revolve around their children’s schedule in order to maintain a certain level of normality around them, to reduce stress. In figure 6 the data shows that online learning has been beneficial with M=2.64, also the perceived adaptability of children had an M=3.30. Lower scores had been recorded for the benefits of the new school environment (M=2.69) and curiosity manifested for the children for the new learning experience (M= 2.70). They also reported that children spent time in online activities (M=3.47) and this could be perceived as either beneficial or not, further data would be needed in order to determine if the online activities were beneficial for the children’s cognitive development and personal development.

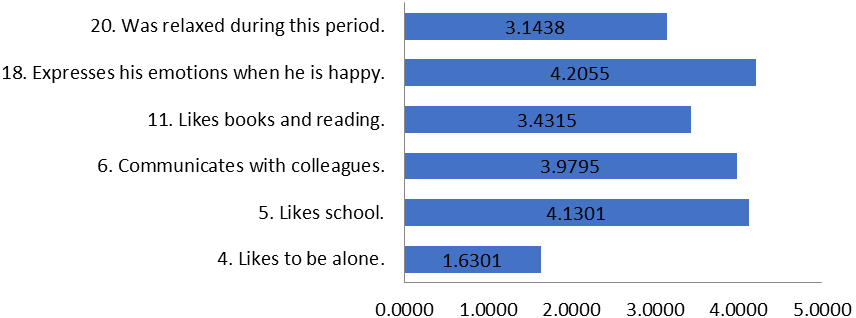

For a better understanding of the results we have also asked the parents about the characteristics of the child, regarding whether he likes to be alone more or if he likes school. The results are presented in figure 7. The scores show that most children express their emotions (M=4.20) and like school (4.13), books and reading as a leisure activity (M=3.43).

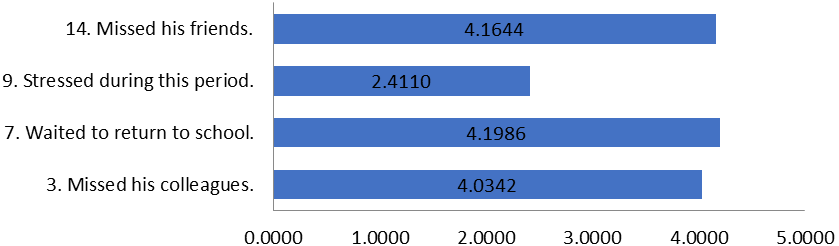

Parents have also reported that children have missed their social interactions (figure 8) since their daily routine from going to school and meeting their colleagues changed. Parents also perceived that their children would prefer to return to school instead of doing classes online (M=4.19). The children were not perceived as stressed in the new learning setting, parents reporting with a lower score (M=2.41).

Conclusion

The new learning environment has been transformed to a new setting. There is still research to be done in order to determine all the benefits and risks that this setting poses for the future of learning. From the current study we have learned that both parents and teachers perceived benefits and also distress in this period for the children. The learning environment has changed and all three parties have encountered serious challenged. Children like spending time at school, in social interactions and being surrounded by their classmates. These findings support a hybrid learning environment for the school setting. This is something that all educators and policy makers should consider. The shifting of the learning process has started and the new image of education perhaps will never be the same again. This is the new normal, and as educators we have a duty to find the best learning settings, the best digital tools and proper communication channels.

Acknowledgments

This work was possible with the financial support of the Operational Programme Human Capital 2014-2020, under the project number POCU 123793 with the title “Researcher, future entrepreneur – New Generation”.

References

Child trend data bank. (2013). Parental involvement in school, indicators on children and youth. https://www.childtrends.org/indicators/parental-involvement-in-schools

DCSF Publications (2008). The Impact of Parental Involvement on Children’s Education. http://thecustodyminefield.com/shared-parenting-research/2008-dscf-the-impact-of-parental-involvement-in-childrens-education/

Galderisi, S., Heinz, A., Kastrup, M., Beezhold, J., & Sartorius, N. (2015). Toward a new definition of mental health. World psychiatry : Official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 14(2), 231–233.

Hiramura, H., Uji, M., Shikai, N., Chen, Z., Matsuoka, N., & Kitamura, T. (2010). Understanding externalizing behavior from children's personality and parenting characteristics. Psychiatry Research, 175(1-2), 142–147.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2014). Happiness, flourishing and life satisfaction.

Kobylińska, D., & Kusev, P. (2019). Flexible emotion regulation: How situational demands and individual differences influence the effectiveness of regulatory strategies. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00072

Lee, B. J., & Yoo, M. S. (2017). What accounts for the variations in children's subjective well-being across nations?: A decomposition method study. Children and Youth Services Review, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.06.065

Patrikakou, E. N., Weissberg, R. P., Redding, S., & Walberg, H. J. (2005). School-family partnerships for children's success. Teachers College Press.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

23 March 2022

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-955-9

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

2

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-803

Subjects

Education, Early Childhood Education, Digital Education, Development, Covid-19

Cite this article as:

Simion, A. (2022). Children’s Emotional Health In The Context Of E-Learning. Parents’ And Teachers’ Perspective. In I. Albulescu, & C. Stan (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development - ERD 2021, vol 2. European Proceedings of Educational Sciences (pp. 204-214). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.22032.20