Abstract

The golden age of childhood brings a number of important changes in a child’s life. Play is the most important source of learning for children and their main concern at preschool age. Kindergarten is a space for play and social experimentation, where the child plays, establishes emotional relationships with adults and children, learns to live in the community and respect the individuality of others, to be tolerant of differences. Thus, the kindergarten meets the need for community and socialization of the child. Positive interactions with colleagues lead to the building-up of friendships, the development of cooperation skills and conflict resolution. However, not all children can easily establish friendships. The purpose of our research aims to highlight the importance of stories, exercise games and role-playing games in order to optimally integrate preschoolers in the mixed group in kindergarten. The research took place over a period of 18 weeks. The methods used in the research were observation and psycho-pedagogical experiment. To test the hypothesis, we used as a research tool an observation grid. The study was attended by 20 preschoolers aged 2-6, from one preschool education unit in Cluj-Napoca town, Romania.

Keywords: Exercise games, integration, mixed group, role-playing games, stories

Introduction

The preschool period, also called the golden age of childhood, brings a number of important changes in the child’s life in four main directions: physical, intellectual, social and personality development. This age contributes to the acquisition of skills, knowledge and aims to develop and establish attitudes that will work throughout life. Children in this period face “leaving home” and entering the kindergarten environment, where they come into contact with other children, overcoming the narrow horizon of the family and which brings with it new requirements, different from those followed and respected in the family (Șchiopu & Verza, 1995).

The game remains the main activity of this stage, but the instructive-educational tasks also appear. During preschool period the game develops, the toys receive more and more meanings, and the books become interesting and attractive. Preschool is a period of discovery of physical reality, human reality and self-discovery. The child discovers that there is an external reality, with its own rules, a world that does not change according to his wishes and which must be taken into account in order to achieve the goals. The human reality with which he has come in contact so far is changing, the child interacting with more and more children, the parents becoming well-defined characters (Șchiopu, 2009).

Attending kindergarten brings a big change: the number of relationships increases, their quality diversifies, there is a need to adapt their behavior in the two educational environments - family and kindergarten. Although the family has the dominant influence, the child faces a new environment. He is no longer the center of the small group (family), but an equal member with the other children in the kindergarten/ group. The child is forced to move from a solitary to a collective existence.

At the beginning of preschool (3 years) another child is perceived as a threat, as a person who can disturb him, take his toys or ruin his constructions. This causes quarrels and conflicts between children. These are more common in boys than in girls, more common with regular partners than with casual partners; the more personal objects are involved in the game, the more violent the conflicts. From the age of 4, another child is perceived as a rival, as a person who stimulates the desire to be overtaken. The socialization of children’s behaviors, the appearance of characteristic features take place in the context of play and compulsory activities, when interpersonal and group relationships are the main ways of relating.

The preschooler gets along very well with others as long as they obey his wishes. Gradually he begins to enjoy himself more and more when he meets other children. He wants to maintain relationships, learns to give up some of his desires in favor of the other and agrees to change his behavior to be accepted as a friend.

Viewed from the point of view of the goals targeted by preschool education programs, socialization has a number of advantages:

the child is included in a group of co-elderly with whom he shares the achievements and failures of a collective activity;

acquires skills of relationships with others and has the opportunity to practice and streamline them (learns and practices various models of relationships, with the rules and limits related to them);

in the relationship with the co-elderly and the adults, other than the parents, they develop and perform a behavior of presentation and self-affirmation, discovering by comparison their capacities and limits;

gains in the autonomy of self-service actions (learns to eat, dress, put on shoes, put clothes in the closet, ask and go to the bathroom, etc.), decision-making and taking responsibility (learns that he is responsible for his own behavior, word, attitude), for the implementation of initiatives (he decides together with the action partners on the subject, the finality, the way to put them into practice), control of his own behavior (Glava & Glava, 2002).

Starting from the premise that play is the main activity of preschoolers and that stories, in addition to taking children into a magical world, of all possibilities, have a strong formative character, we chose to carry out a research in which to verify the hypothesis according to which the systematic use of stories and games in instructive-educational activities creates the premises for the optimal integration in kindergarten of the preschoolers from the mixed group. We chose this topic because I am an teacher in a mixed group, consisting of children aged 2-6 years. In addition to the age difference, the children come from different school backgrounds: some of the children attended this kindergarten in the previous school year, some came from other kindergartens in the city, and some attended the kindergarten abroad. Coming from different backgrounds and being of different ages, we found that there are difficulties of integration. Through the proposed research, we wanted to highlight the way in which stories and games, used systematically, contribute to the optimal integration in the community of preschoolers from the mixed group. It was a little harder for the new children in the group to be accepted by others and to integrate. The preschoolers who were together last year already formed a team, they were close friends, that is why the other children encountered some difficulties in terms of socialization.

The stories and games chosen were integrated into the group activities, being in line with the weekly theme. The chosen activities tried to present to the children various situations, which, in one form or another, capture aspects related to relationships with others, feelings, emotions, appropriate or inappropriate behaviors.

Problem Statement

The observation grid made by us was applied in the pre-experimental and post-experimental stages of our research. This research tool was applied to a number of 20 preschoolers, from State Kindergarten X in Cluj-Napoca, Cluj County, Romania. Preschoolers were aged 2-6 years: 1 child was aged 2-3 years (2 years and 7 months), 4 children were aged 3-4 years, 5 children ranged in age from 4-5 years, and 10 children ranged in age from 5-6 years; we specify that the ages of the children were calculated in the pre-experimental stage. From the gender point of view, there were 11 girls and 9 boys.

The sample of content covers instructive-educational activities that include stories, exercise games and role-playing games belonging to the three categories of activities: personal development activities, freely chosen activities and activities on experiential fields. The actual experiment took place over a period of 16 weeks, 2 activities per week (stories and games), the chosen activities being in compliance with the weekly theme.

Research Questions

The research questions that guided our study are:

What is the impact of the use of stories, exercise games and role-playing games on the optimal community integration of preschoolers in the mixed group?

Does the participation of preschoolers in the mixed group in instructive-educational activities, which include stories, exercise games and role-playing games, determine the increase of their level of integration in the community?

Purpose of the Study

The aim of this research is to highlight the importance of stories, exercise games and role-playing games in order to optimally integrate preschoolers in the mixed group in kindergarten.

Research Methods

Research hypothesis

The experimental approach aims to verify the following hypothesis:

The systematic use of stories, exercise games and role-playing games in instructive-educational activities creates the premises for the optimal integration in kindergarten of preschoolers from the mixed group.

Research variables

The research variables are:

Independent variable:

the systematic use of stories, exercise games and role-playing games in instructional and educational activities;

Dependent variable:

the level of community integration of preschoolers in the mixed group.

The research method we used is observation. In the case of the present research, depending on the degree of involvement of the researcher, the observation is participatory, the observer becomes a member of the group, participates in the proposed activities, without leaving the impression that he is studying them. Regarding the observation situation, it is deliberately induced/ created, the research being based on a certain purpose, clear objectives and a hypothesis. The participatory observation carried out took place in natural observation situations, valorizing, as a research tool, an observation grid, which captures 10 behaviors. In designing the observation grid we used as bibliographic resources the observation guides for preschoolers developed by Petrescu (2011a, 2011b, 2011c).

Based on the observation of the children’s behaviors, we filled in the grid for each child and noted the behavior on a scale from 1 to 4, where 1 represents “never” and 4 “always”. Within the observation grid there is also a section of “Observations”, where we noted any details about certain specific behaviors of children.

Findings

We present below, in a comparative manner - the pre-experimental stage and the post-experimental stage -, the results obtained for each item of the observation grid.

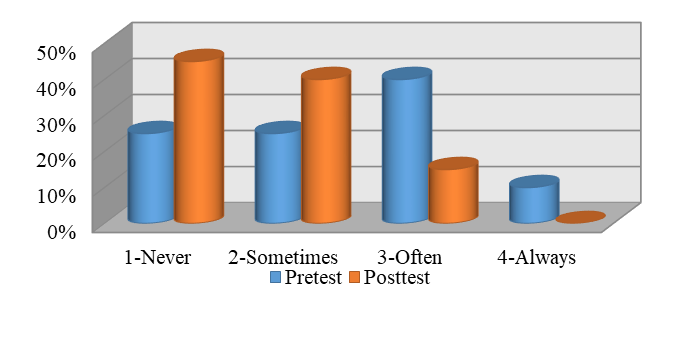

The first behavior, “The preschooler prefers children in the same age group with him.”, shows a 20% increase in the percentage of children who never prefer children of the same age with him (25% in pre-test and 45% in post-test); the percentage of those who sometimes prefer children of the same age (from 25% in pre-test to 40% in post-test) also increased and the number of those who often prefer children in the same age group with him decreased (from 40% in pre-test to 15% in post-test). If in the pre-test there was a percentage of 10% that always achieved this behavior, in the post-test this percentage reached 0% (Figure 1).

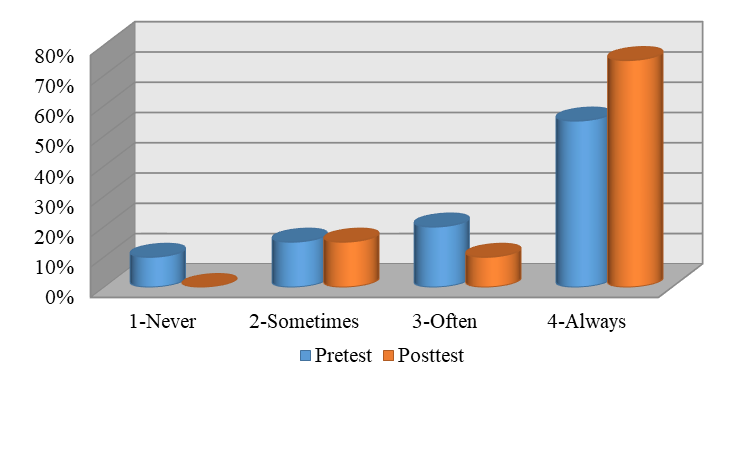

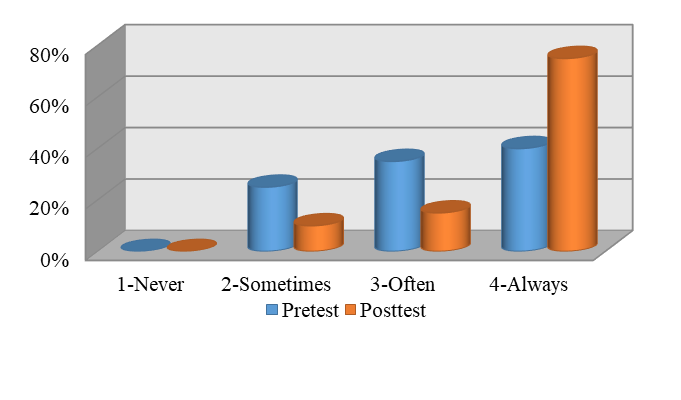

The second behavior, “The preschooler proposes and initiates games and activities that involve more than one child.” shows an increase in the percentage of children who always propose games that involve more than one child, respectively from 55% (in pre-test) to 75% (in post-test). The percentage of children who sometimes achieve the behavior decreased slightly (by 10%) (from 20% in the pre-test to 10% in the post-test). The percentage of children who sometimes initiate games with peers remained constant (15%), and the percentage of children who never engage in behavior decreased from 10% to 0% (Figure 2).

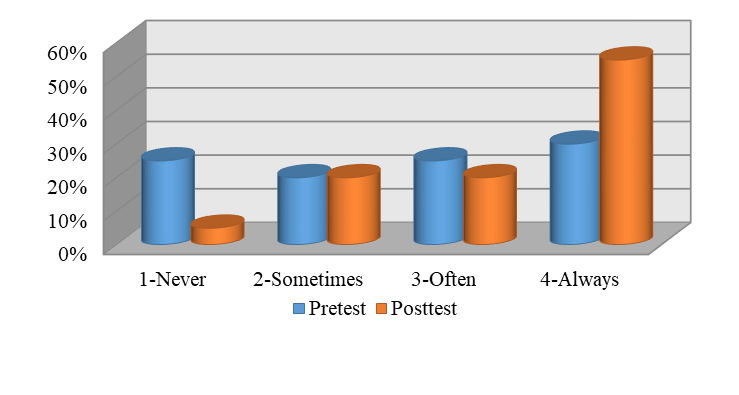

The third behavior, “The preschooler asks for and offers help to the children in the group when he need it,” captures a decrease in the percentage of children who never achieve the behavior - from 25% in the pre-test to 5% in the post-test. The percentage of children who sometimes perform the behavior remained constant (20%). There was also a slight decrease in the percentage of children who ask for and offer help to children in the group when they need it (25% in pre-test, 20% in post-test). The percentage of children who always achieve the behavior increased by 25%, from 30% in the pre-test to 55% in the post-test (Figure 3).

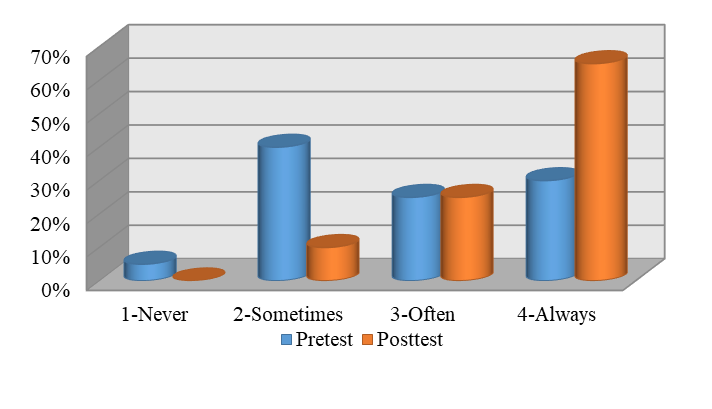

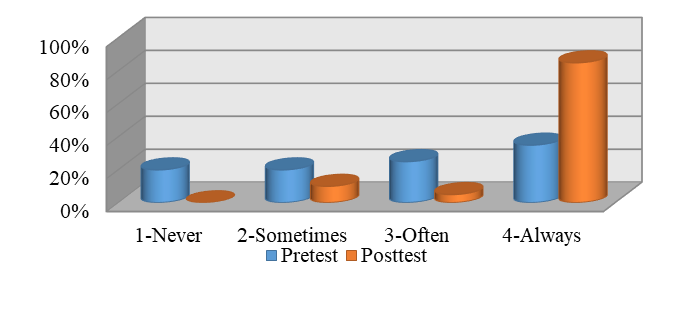

Regarding the fourth behavior, “The preschooler cooperates, exchanges objects in the game.”, the percentage of children who do not exchange objects in the game and never cooperate has decreased from 5% to 0%; the number of children who only occasionally perform the behavior decreased by 30% - from 40% in the pre-test to 10% in the post-test. The percentage of children who cooperate and exchange objects in the game has often remained constant - 25% in both pre-test and post-test. The percentage of children who always achieve the behavior was doubled (30% in pre-test and 65% in post-test) (Figure 4).

The following behavior aims at “observing the game’s rules of the group and the manifestation of fair play (win-win)” and it was always achieved in a percentage of 75% in the post-test, compared to 40% in the pre-test. The percentage of children who often follow the rules of the playgroup (from 35% in the pre-test to 15% in the post-test) and by 15% the percentage of those who perform the behavior only sometimes decreased by 20%. There were no children who never followed the rules in either the pre-test or the post-test (Figure 5).

Regarding the behavior “The preschooler quickly establishes relationships with other children in the group.”, the percentage of children who never achieve the behavior decreased from 20% (in the pre-test) to 0% (in the post-test). There was a slight decrease (10%) in the percentage of children who sometimes perform the behavior - from 20% in the pre-test to 10% in the post-test. If in the pre-test there was a percentage of 25%, which represented the percentage of children who quickly establish relationships with group colleagues often, in the post-test the percentage reached 5%. A higher percentage was registered in the case of children who always perform the behavior, respectively from 35% in pre-test to 85% in post-test (Figure 6).

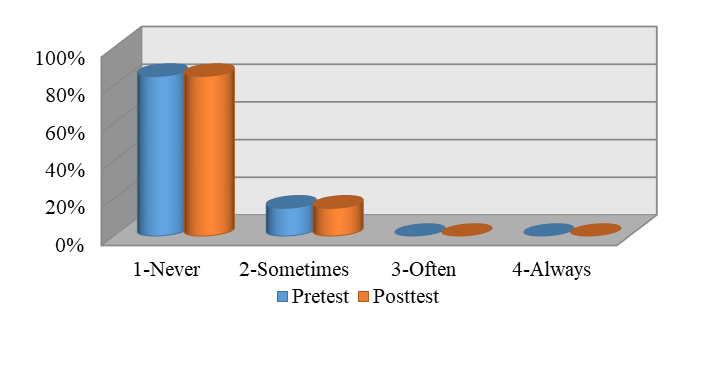

Regarding the behavior “The preschooler doesn’t listen/ ignore the instructions given by the teacher.”, the percentages remained the same. Both in the pre-test and in the post-test, the percentage of children who never listen to the instructions given by the teacher is 85%; the rest of the 15% percentages are the children who sometimes ignore the given indications, for the last two values of the scale the percentages being 0% (Figure 7).

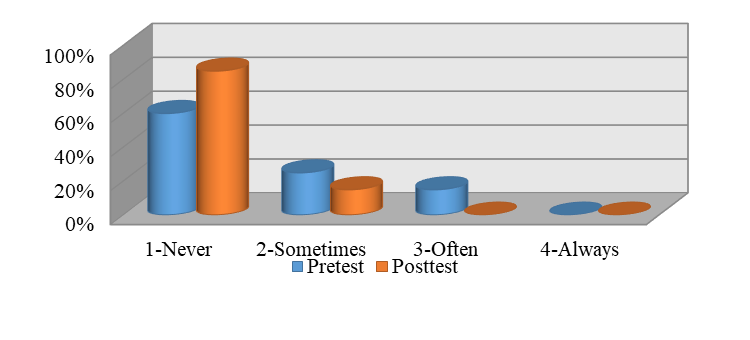

Regarding the behavior “The preschooler doesn’t show interest in activities and doesn’t get involved.”, increased the percentage of children showing interest in activities from 60%, as it was in the pre-test, to 85%, as it was in the post-test. The percentage of children who perform the behavior sometimes decreased slightly (25% in the pre-test, 15% in the post-test); the percentage of children who do not show interest in activities frequently decreased from 15% to 0%. For the last value of the scale there were no percentages in either the pre-test or the post-test (Figure 8).

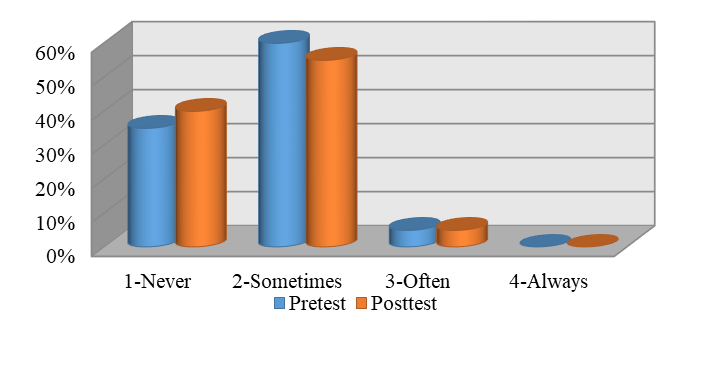

Behavior targeting peer disputes increased slightly in a positive way; percentage of children who never quarrel with colleagues (from 35% in the pre-test, the percentage reached 40% in the post-test) and decreased by 5% the percentage of children who quarrel sometimes (from 60% in the pre-test, the percentage decreased to 55% in the post-test). The percentage of children who often perform the behavior remained constant, respectively 5% both in the pre-test and in the post-test. For the last value of the scale there were no percentages in either the pre-test or the post-test (Figure 9).

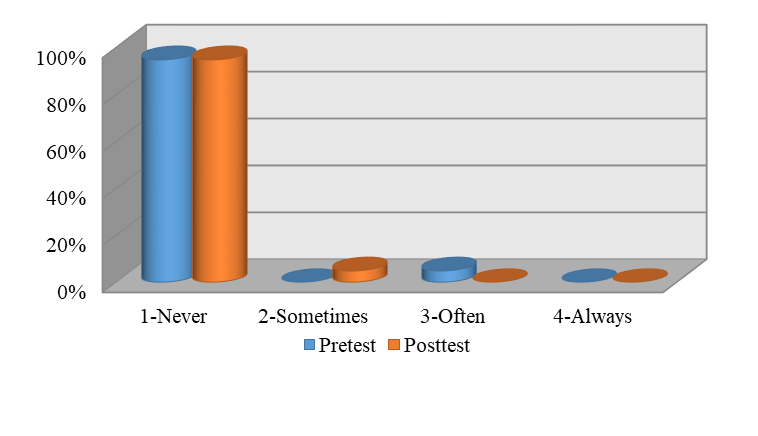

The last behavior refers to aggressive behaviors towards colleagues. The percentage of children who never had aggressive behaviors in the relationship with colleagues remained the same - 95% in both pre-test and post-test. If in the pre-test the second value of the scale had the percentage 0%, in the post-test it increased to 5% (children who sometimes have aggressive manifestations). Regarding the frequent achievement of the behavior, in the pre-test there was a percentage of 5%, reaching 0% in the post-test. For the last value of the scale there were no percentages in either the pre-test or the post-test (Figure 10).

We further present the evolutionary path of three of the preschoolers, each belonging to a different age level.

Preschooler P. T. (aged 3-4) remained constant regarding the first two behaviors, namely “Sometimes he prefers children in the group of the same age with him” and sometimes “The preschooler proposes and initiates games and activities that involve more than one child.”. If in the pre-test he did not ask for and never offered the help of the children when he needed, in the post-test he sometimes realized this behavior. In the case of the behaviors “The preschooler cooperates, exchanges objects in the game”, “The preschooler respects the rules of the play group, showing fair play (lose/ win)” and “The preschooler quickly establishes relationships with other children in the group.” a slight evolution was noticed, i.e. these behaviors came to manifest frequently, compared to the post-test, when they were present only sometimes. In the post-test, the preschooler P. T. came to always listen to the teacher’s instructions, as opposed to the pre-test, when he sometimes ignored them. In terms of the behavior regarding the disputes with colleagues, P. T. sometimes quarreled with colleagues both during the pre-test and in the post-test. If in the pre-test the preschooler was often aggressive with colleagues, during the post-test the aggressive behaviors remained present, but it was manifested only sometimes.

Preschooler R. G. (aged 4-5) remained constant in terms of preference for children in the group of the same age with him and the initiation of games involving several colleagues, these behaviors are always present. If in the pre-test he sometimes asked for and offered help to the children in the group when he needed it, in the post-test period he always got to do it. Progress is also observed in terms of the behaviors “The preschooler cooperates, exchanges objects in the game.”, “The preschooler respects the rules of the playgroup, showing fair play (lose/ win).” and “The preschooler quickly establishes relationships with other children in the group.”; if at the beginning these behaviors were often frequent, in the end they always came to be present. The interest given by the teachers, interest in activities and aggressive behaviors towards colleagues was also maintained constantly: always listens to the instructions given, shows interest in activities, is actively involved, never having aggressive manifestations in the relationship with colleagues. In the pre-test, he sometimes argued with his colleagues, but during the post-test, this behavior became absent.

The preschooler D. M. (aged 5-6) prefers, during the pre-test, sometimes the children in the group of the same age with him, reaching to realize this behavior to a lesser extent (sometimes). In the pre-test, he often proposes games that involve his colleagues, always doing so during the post-test. At the beginning of the research, he sometimes asked for and offered the help of the children when he needed and sometimes exchanged objects in the game, and at the end of the research, the two behaviors became more frequent (they often manifested). If at the beginning the rules of the playgroup were often followed and he frequently established relationships quickly with the other children in the group, in the post-test, these behaviors always became present. It was kept constant in terms of listening to the instructions given by the teachers, the interest in activities, the discussions with colleagues and the aggressive behaviors regarding them: never ignores the instructions given by the teacher, always shows interest in activities and gets involved, sometimes quarrels with colleagues, but never has aggressive behaviors in relation to them.

Conclusion

The research wanted to verify the hypothesis that the systematic use of stories, exercise games and role-playing games in instructive-educational activities creates the premises for the optimal integration in kindergarten of the preschoolers from the mixed group. Undoubtedly, the experiment contributed to the optimal integration of children in kindergarten, but did not contribute to it alone. The progress made by children is not only due to the stories and games made, but to the whole instructive-educational process, to which we add the informal and non-formal influences. It is true that preschoolers aged 3-4 progress regardless of their activity, but it is a long process. The systematic use of stories and games helped children progress at a faster pace, the results being visible even during the actual experiment: the children started playing with each other regardless of age, they became more understanding in their relationship with their peers, they received confidence to express themselves freely, they became more attentive and active in activities, more interested, they improved their relationship with the teacher, but also with their colleagues.

An important role was played by the teacher; it is essential how he manages to approach children and communicate with them, to play the role of actor, the way he relates to children, the emotional relationships between him and children. The educational climate is required in this case as well. Thus, a teacher with pedagogical tact, creative, endowed with patience and confidence in children and a positive educational climate - all this ensures the success of a day in kindergarten.

Another important role belongs to the kindergarten counselor, who carried out weekly activities aimed at the socio-emotional development of children. Learning about emotions, about how we manifest ourselves in certain situations, about how we should react, children have become much more open to those around them, especially in the relationship with group colleagues, regardless of their age.

Regarding the limits of the research, we mention the fact that the experimental group was composed of only 20 subjects, there being no control group.

Although there has been progress in the relationship with colleagues and the teacher, we have seen that there is still a certain percentage that highlights preschoolers who have not had the expected progress. Here is the age difference between children and the problems that some children face (aggressive manifestations).

A disadvantage would be the existence of groups of children formed in the previous school year; 4-5 aged group and 5-6 aged group children attended kindergarten last year, for which there was a closer connection between them.

Another disadvantage regarding the relevance of the research is related to the frequency of children in kindergarten. Not all the children attended the kindergarten on the days when the games and stories were made. However, there was a daily percentage of at least 70% of subjects present in kindergarten.

In conclusion, we consider that the proposed research verified the hypothesis, being able to be verified by any teacher from the mixed group. Even if the progress made will not be the same, evolution in the sphere of integration in the community will still exist.

References

Glava, A., Glava, C. (2002). Introducere în pedagogia preşcolară [Introduction to preschool pedagogy]. Cluj-Napoca: Editura Dacia.

Petrescu, C. (Coord.) (2011a). Ghid de observare a copilului. Grupa mică – 3-4 ani [Child observation guide. Small group - 3-4 years]. Piteşti: Editura Diana.

Petrescu, C. (Coord.) (2011b). Ghid de observare a copilului. Grupa mijlocie – 4-5 ani [Child observation guide. Medium group - 4-5 years]. Piteşti: Editura Diana.

Petrescu, C. (Coord.) (2011c). Ghid de observare a copilului. Grupa mare – 5-6 ani [Child observation guide. Large group - 5-6 years]. Piteşti: Editura Diana.

Şchiopu, U. (2009). Psihologia copilului [Child psychology]. Bucureşti: Editura România Press.

Şchiopu, U., & Verza, E. (1995). Psihologia vârstelor – ciclurile vieţii [Age psychology - life cycles]. Bucureşti: Editura Didactică şi Pedagogică.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

23 March 2022

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-955-9

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

2

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-803

Subjects

Education, Early Childhood Education, Digital Education, Development, Covid-19

Cite this article as:

Câmpan, A., & Bocoș, M. (2022). Carrying Out The Instructive-Educational Activities For Optimal Integration Of Preschoolers. In I. Albulescu, & C. Stan (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development - ERD 2021, vol 2. European Proceedings of Educational Sciences (pp. 1-12). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.22032.1