Abstract

The study examined the peculiarities of Russian girls’ body image. Participants included 136 Russian teenage (13-15). All the girls already got menarches. To obtain the data used questionnaire and projective measures. Results indicated that teenage girls demonstrate «normative discontent» with the body. Most teenage girls aged 13-15 are characterized by a low degree of body acceptance, and by a significant gap between the images of a real and ideal body. Teenagers’ self-respect and self-incrimination depend on positivity / negativity of the body image. Functional characteristics of the body and positive body image are connected both with external and internal standards of teenage girls. Correlation analysis of body image parameters with body mass index (BMI) showed that there were negative correlations of degree of compliance with external standards and assessment of physique with data of display (-0.34 and -0.40, respectively, p ≤ 0.01). At the same time, the relationship of BMI and compliance of the body with girls' own internal standards of a teenager girl was not revealed. About 40% of adolescent girls had a negative body image, 30% of the girls had a positive one, and the rest had an ambivalent one. Belonging to a particular group did not depend on BMI.

Keywords: Body imageteenage girlsVCOPASBSQ

Introduction

Adolescence is a critical period for the body image development due to physical, psychological, and social changes occurring at the age of 12 – 17. One of the main factors determining the formation of the body image in adolescence is puberty. Morphological changes occur in teenagers of both sexes and affect the image of the body. Weight concern is one of the main factors that create dissatisfaction with a body. The model form, the one which is considered attractive, often cannot be achieved by most teenagers, therefore they try extreme weight loss diets, detrimental practices for weight control, excessive use of diuretics and laxatives, vomiting, or excessive physical activity.

Much research around the world deals with studying gender issues of body image in adolescence. The results of one Norwegian study showed that the number of texts on poor health by adolescents increased with age. Girls text about poor health more often than boys do, while boys and 11-year-olds text more about excellent health. As one gets older, the effect of gender on the characteristics of health is only growing. Girls, who mentioned restrictive eating behaviour or dissatisfaction with their weight, who considered themselves fat, were more likely to talk about poor health. The number of girls restricting themselves in food is growing as the girls get older. The authors supposed that gender differences in the relationship between body dissatisfaction and health indicators appeared to be mediated by diet (Meland, Haugland, & Breidablik, 2007). A study conducted among young people in Sweden demonstrated that obesity, as well as underweight, was indeed linked to the subjective feeling of ill health in this group (Hagquist, 1998). A survey among English teenagers showed that half of the girls and one in three boys were worried about their bodies. Twice as many girls wanted to lose weight (Meland et al., 2007). The tendency is not new: back in the 1960s, Douvan E. and Adelson J. found that over 60% of secondary school girls wanted to change their appearance compared to 27% of boys (as cited in Douvan & Adelson, 1966).

On the one hand, gender differences can be explained by the onset of puberty, and boys’ and girls’ peculiarities. During maturation adipose tissue is growing in girls, which increases the gap between the real and ideal body image. Early maturing girls are more committed to a slender ideal than their peers whose menarche age comes later (Voelker, Reel, & Greenleaf, 2015). Girls with an early menarche onset are thus more vulnerable than their peers.

Problem Statement

In addition to searching for biological correlations of the body image, researchers are increasingly attracted by the analysis of socio-cultural factors that determine the adolescents' body image. We have to note the negative impact of digital media and social networks on the image of the body in adolescence. Ashikali, Dittmar, and Ayers (2014) showed that 15-18-year-old girls who watched a cosmetic surgical show reported greater dissatisfaction with weight and appearance compared to the control group, watching a TV show not related to the body image (Ashikali et al., 2014). Tiggemann and Slater (2013) note that among 13-15-year-old girls, problems with the body image increase depending on the time spent on the Internet and on Facebook in particular.

Family factors are crucial for the formation of the body image in adolescents. In a longitudinal study Helfert and Warschburger (2011) found that the parents' encouragement of restrictive eating behaviour and weight control was connected with the increased weight in senior students of both sexes.

Some research focuses on parental modelling and parental attitudes (Amianto et al., 2016). Parental modelling means that parents implicitly convey their beliefs to children and demonstrate behaviour that will necessarily affect children. Parents' restrictive eating behaviour and discontent with their body will contribute to the unhealthy habits of children and their negative beliefs about their own bodies (Arroyo, Segrin, & Andersen, 2017). However, there was also a positive modelling effect: regular family meals were associated with proper eating habits in children (Fulkerson et al., 2006).

For a teenager, besides a family, peers and reference groups in which a teenager is included are of special importance. In a number of studies the determining influence on the formation of teenagers' body image of the peers' position was revealed. Various mechanisms are involved, such as criticism or nastiness, discussion of problems related to appearance, comparison of appearance, judgements about the appearance of friends, and isolation of a teenager (Webb & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2014).

The influence of romantic relationships on the body image of a teenager is less studied, but it is shown that girls consider slenderness a decisive factor of their attractiveness, and 85% of boys really consider slender girls more attractive (Paxton, Norris, Wertheim, Durkin, & Anderson, 2005).

Research Questions

The research question of the study is;

What is the specificity of the body image of teenage girls aged 13-14 and how the body image depends on feedback from parents?

Purpose of the Study

Our goal was to describe the components of the body image of teenage girls.

Research Methods

To obtain the data we used questionnaire and projective measures. 'Body characteristics inventory' by Belogai K. was constructed based on Semantic differential by Charles E. Osgood (Osgood, 1952). It includes such scales as positive body image, functional characteristics (power, flexibility etc.), activity and body type assessment. In 'Life Dynamics of Satisfaction with the External Image' by Belugina adolescent girls were to assess on a ten-point scale the degree of satisfaction with their body when they were 5 years old, 10 years old and at the present time. 'Self-portrait' projective measure with the following instruction: 'First draw how you see your body and then what you want it to look like. Use coloured pencils'. All the girls of the study participated in a semi-structured interview aimed at obtaining information on height, weight (for calculating the body mass index (BMI), the characteristics of the menstrual cycle, their own attitude toward the body (including the desire to change something in the body), the attitude towards the body from significant people (a mother or a father), and their lifestyle (about diets or other variants of restrictive eating behaviour, sports or dancing). They were also asked to evaluate the compliance with external and internal standards.

Statistic methods

STATISTICA 6.0 (descriptive statistics, t-test, correlation analysis, ANOVA (Analysis of variance) and cluster analysis were used to process the data.

Sample

136 girls aged 13-15 took part in the study of the body image. All the girls already got menarches. The respondents provided oral consent to participate, and were informed that they could complete it at any time. The participants were explained the procedure and purpose of the study. The instructions for each method were presented in an oral and written form. The time was not limited. Parents also gave their consent to the girls’ participation in the study.

Findings

Descriptive statistics for this sample are given in Table

Information and evaluation component of the body image was characterized by low estimates of the conformity degree of the body to external and internal standards (with a sufficiently significant variation of estimates), low estimates of an activity, functionality of the body. The body appeared to the girls rather large and fat.

The analysis of the temporal and energy components of the body image showed that the estimates of the appearance given by adolescents had the highest values for preschool childhood, decreased at school age and were the lowest at present time. The indicators of body acceptance, evaluation of functional characteristics, physique and activity in adolescence were not high, although in this regard the group of adolescents was heterogeneous.

The spatial component of the body image was evaluated by picture analysis. Analysis of teenage girls' pictures confirmed the high degree of body dissatisfaction among modern teens. In the drawings we could see a significant gap between the real and ideal body image. In some cases, the real body was represented in one colour, the ideal one was multicoloured. In other cases, the drawing of the ideal body was realistic, whereas the real one was extremely schematic. In the pictures of 40% of girls the ideal body was emphatically feminine, depicted in a dress, skirt, with long hair and accessories.

The main biological factor influencing the formation of the body image of a teenage girl is menarche. The search for correlations between the menarche onset and the parameters of the body image showed that this objective criterion was related to activity and functionality (correlation coefficients are 0.35 and 0.4, respectively, p ≤ 0.01).

We also tested the influence of menarche onset on the energy and information and evaluation components of the body image using a single-factor dispersion analysis. We found, that the later the menarche came, the higher the girl estimated the degree of compliance with external standards (p ≤ 0.02). The degree of compliance of the body with internal standards on the age of menarche onset was not revealed.

The group of adolescents was extremely heterogeneous in terms of compliance with external and internal standards. The average values for these parameters were 61.1% and 63.6% respectively. That is, compliance with own ideals was slightly higher. Five percent of girls indicated 0%, 5%, 10% when answering questions about compliance. Girls' compliance assessment of their own ideals positively correlated with the assessment of compliance with external standards (correlation coefficient 0.70, at p ≤ 0.01).

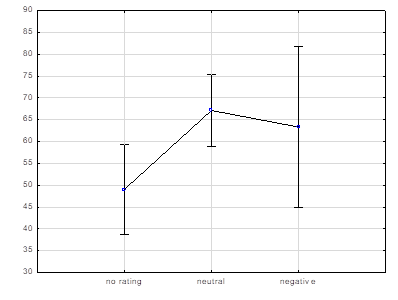

Correlation analysis of body image parameters with body mass index showed that there were negative correlations of degree of compliance with external standards and assessment of physique with data of display (-0.34 and -0.40, respectively, p ≤ 0.01). At the same time, the relationship of BMI and compliance of the body with girls' own internal standards of a teenager girl was not revealed. In an interview, we asked the girls In the opinion, what their mothers think of their bodies. As a result, three groups of girls were identified: one group responded that 'mothers do not evaluate their body', the second group described the evaluation as neutral, and the third one pointed to negative attitudes and the fact that the girl needed to lose weight (Figure

Thus, our study revealed the influence of mothers’ messages on the body image that is formed in adolescence, in particular, on acceptance of the body by a teenager.

Considering the behavioural component of the body image, we primarily focused on the problem of the implementation of restrictive eating behaviour by teenagers. Three groups of girls were identified: without restrictive eating behaviour, a group seeking to eat healthy foods and a group regularly resorting to diets (with a 'rigid' restrictive behaviour strategy). The evaluation component of the body image differed significantly in these groups. The group for which restrictive eating behaviour was not characteristic has the highest physique rating; the group with soft strategy had the highest acceptance rate. Estimates of functionality and activity were practically the same in girls with restrictive behaviour and slightly lower in girls without such behaviour. The group with a tough strategy had the lowest physique ratings.

In addition to girls’ eating behaviour, we were interested in their desire to change something in the body. According to the survey, 72% of teenagers would like to change something in their bodies: to reduce waist size, height (8% of teenagers would like to get higher) and weight (12% of teenagers would like to lose weight). 28% of respondents would like to change 'everything' in their body. The desire to change something in the body, as some authors believe, is a predictor of the global body image dissatisfaction (Kostanski & Gullone, 1998).

To analyze the results, a cluster analysis was carried out by means of a complete-link hierarchical clustering. As a result, three clusters were obtained, for the description of which we carried out clustering of data by the k-means method (Table

The first group included girls with a positive body image. They were characterized by the highest (compared to the other two groups) assessments of the body, its functional characteristics, body acceptance, high assessments of the degree of conformity of the body to the external and internal standard. Teenage girls with positive body image show a decrease in body satisfaction in the transition from childhood to adolescence, but the decline is less pronounced. Girls of this group had an internal locus of control and high parameters of personal self-conception (except self-accusation), that is a positive I-concept. Estimates of body functionality and activity in this group were positive, though not too high (but also significantly different from the other two groups). Almost a third of adolescent girls had a positive body image.

The second group included teenage girls with an ambivalent body image. Girls in this group assessed the degree of compliance with external and internal standards lower; they saw their body large and fat, while BMI of this type and BMI of girls with positive body did not differ in a significant way. Adolescents with an ambivalent body image assessed the functionality of the body significantly lower. 26% of girls made up the second group.

Teenage girls of the third group had a negative body image – the lowest estimates of compliance with external and internal standards, low estimates of body functionality and activity, the sharpest decrease of the degree of body acceptance in adolescence. This group of teenagers had the lowest rates of self-esteem (except for self-accusation and internal conflict). This group included 43% of the girls.

The assumption that the girls of the selected types had different weight or physique was not confirmed; BMI, weight and height almost coincided in the selected groups. It can be said that girls with a positive body image had or partially had a protective filter that did not allow external stereotypes to adversely affect the body image and self-attitude of teenagers, girls with ambivalent body image had only a partially formed protective filter, girls with negative body image had no filter at all.

Conclusion

The body image is a product of the reflection of a person's mind by the psyche. The formation of the body image is influenced by many factors. Socio-cultural ones – the family environment, the relationship with peers, the media and cultural traditions – are essential.

Most teenage girls aged 13-15 were characterized by a low degree of body acceptance, by a significant gap between the images of a real and ideal body. The self-respect and self-incrimination of girls depended on the degree of positive – negative body image. Functional characteristics of the body, positive body image were connected both with external standards and with the internal standards of the teenage girls.

About 40% of adolescent girls had a negative body image, 30% of the girls had a positive one, and the rest had an ambivalent one. Belonging to a particular group did not depend on BMI.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Russian Foundation for Basic Research (RFBR) under Grant 20-013-00110.

References

- Amianto, F., Northoff, G., Abbate Daga, G., Fassino, S., & Tasca, G. A. (2016). Is anorexia nervosa a disorder of the self? A psychological approach. Frontiers in psychology, 7, 849.

- Arroyo, A., Segrin, C., & Andersen, K. K. (2017). Intergenerational transmission of disordered eating: Direct and indirect maternal communication among grandmothers, mothers, and daughters. Body Image, 20, 107-115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j .bodyim.2017.01.001

- Ashikali, E. M., Dittmar, H., & Ayers, S. (2014). The effect of cosmetic surgery reality tv shows on adolescent girls’ body image. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 3(3), 141. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105314522677

- Douvan, E. A. M., & Adelson, J. (1966). The adolescent experience. Wiley.

- Fulkerson, J. A., Story, M., Mellin, A., Leffert, N., Neumark-Sztainer, D., & French, S. A. (2006). Family dinner meal frequency and adolescent development: Relationships with developmental assets and high-risk behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(3), 337-345 https://doi.org/10.1016/j .jadohealth.2005.12.026

- Hagquist, C. E. (1998). Economic stress and perceived health among adolescents in Sweden. Journal of Adolescent Health, 22(3), 250-257.

- Helfert, S., & Warschburger, P. (2011). A prospective study on the impact of peer and parental pressure on body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls and boys. Body image, 8(2), 101-109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j .bodyim.2011.01.004

- Kostanski, M., & Gullone, E. (1998). Adolescent body image dissatisfaction: relationships with self‐esteem, anxiety, and depression controlling for body mass. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 39(2), 255-262.

- Meland, E., Haugland, S., & Breidablik, H. J. (2007). Body image and perceived health in adolescence. Health Education Research, 22(3), 342-350. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyl085

- Osgood, C. E. (1952). The nature and measurement of meaning. Psychological bulletin, 49(3), 197.

- Paxton, S. J., Norris, M., Wertheim, E. H., Durkin, S. J., & Anderson, J. (2005). Body dissatisfaction, dating, and importance of thinness to attractiveness in adolescent girls. Sex Roles, 53(9), 663-675. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-7732-5

- Tiggemann, M., & Slater, A. (2013). NetGirls: The Internet, Facebook, and body image concern in adolescent girls. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 46(6), 630-633. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat .22141

- Voelker, D. K., Reel, J. J., & Greenleaf, C. (2015). Weight status and body image perceptions in adolescents: current perspectives. Adolescent health, medicine and therapeutics, 6, 149. https://doi.org/10.2147/AHMT .S68344

- Webb, H. J., & Zimmer‐Gembeck, M. J. (2014). The role of friends and peers in adolescent body dissatisfaction: A review and critique of 15 years of research. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24(4), 564-590. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12084

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 December 2020

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-951-1

Publisher

European Publisher

Volume

1

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-322

Subjects

Cognitive psychology, education, educational psychology, teacher training, social psychology, group psychology,

Cite this article as:

Belogai, K. N., Morozova, I. S., Novoklinova, A. V., & Borisenko, J. V. (2020). Body Image In Teenage Girls. In I. Elkina, & S. Ivanova (Eds.), Cognitive - Social, and Behavioural Sciences - icCSBs 2020, vol 1. European Proceedings of Educational Sciences (pp. 253-260). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epes.20121.29